INTRO:

This would sound like a statement that is just too personal for a review, but I have to say here that I am not easy to be amused by video games these days. Games that make a poor first impression on me often get overlooked. Even those games which actually have something substantial beyond a poor impression would have me doing little more than watching other people play them.

Undertale – created almost entirely by one-man developer Toby Fox – would have been a game that is both of the above. There were murmurs that it relies on a lot of nostalgia to draw people in, specifically nostalgia for the Mother series (a.k.a. Earthbound), and not everyone is into nostalgic sentiments (myself included). There was gushing over how the game drubs expectations and lampshades many video game tropes, but Undertale would not have been the first game to do that which I know of. (The only reason for me not having watched someone else play it is that reading text in videos is not something which I like to do, and Undertale is text-heavy.)

Fortunately, thanks to a hefty discount at a digital distributor which I frequent, I have an opportunity to experience the game first-hand. It would turn out to be one of the most worthwhile game-consuming decisions which I have made; elaborations to follow.

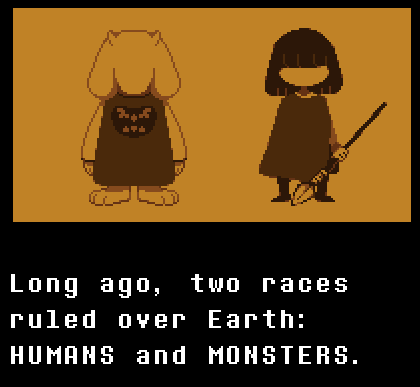

PREMISE:

The game takes place in a seemingly fantastical world with some modern-day and sci-fi elements; players who are experienced in Japanese RPGs would find this setting rather familiar.

Undertale takes place in an (expectedly) subterranean realm, which was populated by “Monsters” after a disastrous war with this game’s ‘humans’. It was not exactly the best place for the Monsters, but they have since settled the underground in relative peace. Unfortunately, recent events involving the death of much-beloved members of the ruling family have driven the underworld to the precipice.

Into this realm falls an ambiguously gendered human child, for whatever reason that is not told to the player. The human child would soon be the one who decides the fate of the underworld and its Monster inhabitants. Throughout the game, there would be many who would try to block his/her way, kill him/her, and/or manipulate him/her – while trying to befriend him/her in awkward and sometimes inappropriate ways.

Complicated narratives are nothing new in video games, but Undertale has one that is inanely and hilariously silly, thanks to a cast of rather colourful characters.

MOVEMENT IN OVERWORLD:

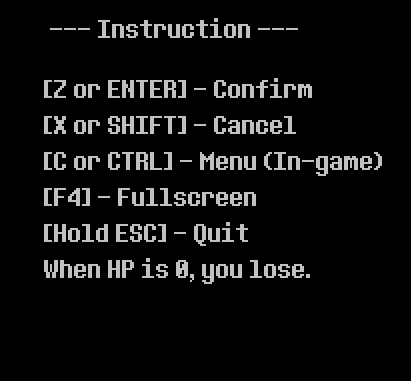

The underworld is seen from an isometric top-down point of view. For convenient reference, this view would be referred to as the “overworld”. In the overworld, the player character, who is the aforementioned human child, can only move in the cardinal directions. There is no smooth diagonal movement. Most of the time, this is not an issue, but there are scenarios where this would have been useful, such as cutting corners during a chase.

INTERACTING WITH THINGS:

The player can examine things which the player character is adjacent to. As for anything which is further away, there is not much which the player can do. The player cannot even make observations on these, assuming that they are within the screen in the first place. Furthermore, things can only be examined if they are immediately to the north, east, south and west of the protagonist, who also has to be facing them too. This can be tedious at times, especially if there are puzzles where the player must examine things in order to obtain hints on the solutions.

Considering that the game has been designed for the computer platform, having a mouse cursor for the purpose of clicking on things to examine them from afar would have been useful. Besides, there are many things which do not exactly look like things that a human player would immediately recognize.

‘CONVERSATIONS’:

If the thing which the player wants to interact with is an actual character, the character usually utters a statement or two. Sometimes, conversations can be struck during ‘hostile’ encounters or at their end.

Ultimately, most of the conversations are one-way; the protagonist is a taciturn person who expresses himself/herself through deeds more often than words. The most which the player could do is select one of the options which are presented at certain junctions of the conversation. Usually, none of the options is of any major significance – unless they are clearly binary decisions.

Speaking of which, the clearly binary decisions will be pivotal to whether a character would survive until the epilogue or not. Obviously, players who want these characters to contribute more to the story – or just utter more things – might want to take great notice of these decisions.

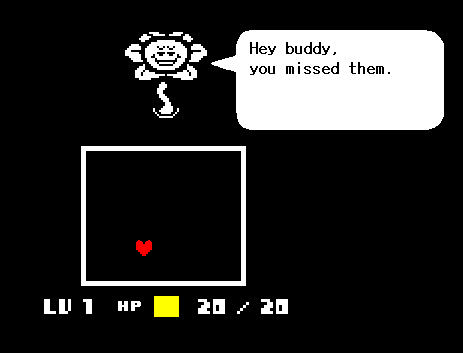

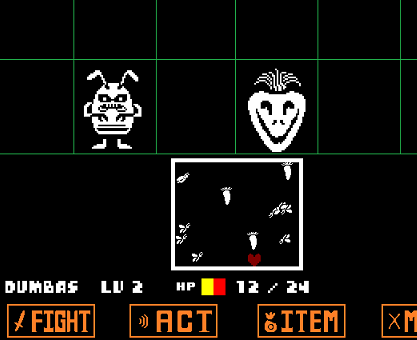

BULLET BOARD SCREEN:

There is some form of combat in this game, but to call it “combat” is to have expectations of violent conflict and similarly violent resolution. This is not always the case for every confrontation with other characters.

When not-exactly-peaceful encounters occurs (using the word “hostile” to describe the encounters is an overstatement most of the time), the player is brought to the “bullet board” screen. This screen is also used for some scenarios where Toby Fox thought that, for whatever reason, the UI would be a better way to get some messages across. Incidentally, most of the animations for characters are seen in this screen. The elements of the bullet board screen are described in later sections.

THE SOUL HEART:

For whatever reason, whenever the bullet board screen is brought up, the player character is turned into a red heart. There is some in-game explanation for this, e.g. Monsters have a far better grasp of magic than humans do, so much so that in ‘magical combat’, humans are reduced to floating heart-souls. This is of course just a silly narrative excuse for this presentation.

Anyway, the heart is also used as an icon that indicates which option the player is selecting, when the eponymous bullet board is not appearing on screen. This might seem trivial, but it does matter in a certain ultimate fight against a certain character.

If the heart comes into contact with almost anything other than the boundaries of the bullet board (more on this later), damage is inflicted on the player character. However, immediately afterwards, the heart flashes; this is, of course, the invulnerability frames which it has. Under regular conditions, the heart can move around and cannot be further damaged while it flashes. The frames last for a very short while, but there is at least one piece of gear which extends the duration of the invulnerability frames.

(The aforementioned ultimate fight happens to disable the invincibility frames, however.)

BOARD BOUNDARIES:

The eponymous “bullet board” of the bullet board screen is represented by a rectangle in the bottom middle region. The rectangle represents the boundaries in which the player’s heart can move about.

During fights with regular unnamed Monsters, the rectangle is mostly fixed in size. However, in the case of some Monsters (especially the ones who are important to the story), the dimensions of the rectangle can change from turn to turn, depending on the attacks which the player’s opponent uses.

Interestingly, not everything which the player’s heart has to dodge will appear within the rectangle’s boundaries. Some threats can appear outside of the rectangle, eventually making their way into the rectangle, and sometimes even out of it and back again; these tend to be dense barrages, so the advance warning is much appreciated.

HEART/SOUL COLORS:

By default, the player’s Heart is red. In this state, it can move anywhere within the bullet board along any direction, including diagonal movement. The red state is what the player’s heart is in most of the time, which is just as well because it is the one that would be doing a lot of dodging.

Interestingly, there is an additional control input which is not told to the player during the tutorial chapter. Rather, the player would have to discover this via curiosity. Anyway, this is the ability to slow down the heart’s movement. Although generally undesirable, this might be useful in navigating narrow but fixed paths through hazards.

There are other colors, each of which is gradually introduced to the player. The player has no control over which of these colors is used; they are often forced upon the player by the opponent instead. (There is, of course, a narrative excuse for this: monsters can work magic, most humans don’t.)

First of these other colors is blue, which imposes laws of gravity on the player’s heart. The blue heart can “jump”; observant players will also notice that they have considerable “air control” (i.e. the ability to move the heart about while it is in mid-jump). Another notable colour is yellow. When the yellow heart is active, it is practically the player ship of a simple shoot-‘em-up.

The other colours would have been described here; after all, they have gameplay significance of their own. However, their presence in the gameplay is so much less than that of the red heart; in fact, they only appear in specific scenarios.

Unfortunately, in hindsight, the lacking presence of the other heart colours can give the impression that an opportunity to diversify the gameplay has been wasted. The gameplay in the bullet board screens could have been more entertaining if the player could freely switch between the colours, and if there have been scenarios where switching colours would be useful.

SAVE-POINTS:

Throughout the underworld, there are peculiar 4-pointed stars. The player character can use these, thanks to a certain trait which he/she has and which will not be described here.

Players who are experienced with 16-bit era Japanese RPGs would recognize these almost immediately as “save-points”. Like the save-points of yore, these allow the player to record his/her progress in a playthrough. However, there is officially only one save-file which the game would handle; if the player wants any more save-files, he/she would have to make back-ups of the save-files (something which is easy to do). This has to be done if the player wishes to make different decisions at certain points in the story progression.

HIT-POINTS:

Hit-points are obviously the amount of damage which the player character can take before ‘dying’. The amount of hit-points which the player character starts with is 20; more can be gained by gaining ‘LOVE’ levels (more on this shortly).

The main way of restoring hit-points is to save at save-points. (The player is also given an inane description of how the protagonist seems to regain resolve from just about anything.) Of course, backtracking to a save-point is not always feasible, especially in places where there are considerable rates of random encounters with Monsters of half-hearted hostility.

The other ways to regain hit-points are eating food and using obvious video game healing items like potions and bandages. This can be freely done outside of the bullet board screen, but during combat, consuming or using items counts as spending a turn.

DEATH & RELOADING:

Obviously, losing all hit-points leads to death – in most cases. However, thanks to a trait which the player character (somehow) has, death is not the end. The player is simply returned to the last save-point which was used.

This is, of course, nothing new in the history of video games, at least from a technical perspective. Yet, there is a curious narrative-related thing about this; observant players might notice peculiarities such as a few other characters having déjà vu upon meeting the player character for the specific n-th time. This is actually significant to the penultimate sections of the game, if the player has bothered to keep this in mind.

“GOLD”:

Presumably, the underworld uses the typical currency that is used in so many RPGs: gold. Of course, considering that Toby Fox has a tendency to try to turn a video game trope on its head, this might be something else instead as it is spelled with capital letters in-game. However, if it is something else, it is not explained.

Anyway, GOLD is the currency which Monsters carry around on their persons. It can be obtained from elsewhere, but the main source is still from the pockets of Monsters (assuming that they have pockets). There are two ways to take GOLD from Monsters: either looting it off their dusty remains, or (presumably) having them give some to the player character after they have been “spared”.

The player will be using GOLD mainly to buy things, most of which would likely be healing items. There are other purchasable items such as pieces of gear, though there are few of these.

GEAR:

There are only two types of items which the player character can wear on his/her person: “armor” and “weapons”. The gear pieces which are categorized under “armor” are anything but armor; most of them appear to be mundane or even absurd stuff like bandages and a tutu. On the other hand, they still have “defense” ratings which do translate to additional damage reduction for the player character.

Weapons are similarly whimsical: toy knives, frying pans and the likes are the utensils of ‘combat’ which the protagonist can use. (There is one actual weapon in the game, though it is only available if the player has adopted a certain ‘playstyle’.) They have “attack” ratings, but it is not clear how exactly these quantities contribute to the damage output of the player character’s attacks, other than the simple fact that higher attack ratings mean higher damage output.

Perhaps the greatest significance of “armor” and “weapons” is their subtle contribution to the narrative; the gear which the human protagonist can wear happens to be originated from other humans who were previously in the underworld. There is no other explanation which is as clear as this though, so this matter is up to (a lot of) speculation by fans.

“LOVE”:

Like any other RPG which includes combat as a gameplay feature, Undertale has a progression system which uses points that are gained by killing enemies. These points are called “EXP” in-game, which would be an abbreviation that RPG followers are all too familiar with. There are also “EXP” thresholds which indicate when the player gains “LV”, which is called “LOVE” in this game.

Yet, after a certain character explains this in the prologue, a skeptical player would be having suspicions that this is not entirely the usual experience points and levels that can be found in typical RPGs. After all, said character would reveal its treacherous intent rather early on.

Anyway, the player can only gain EXP by killing Monsters. Gaining LOVE increases the player character’s hit-points, and also seems to increase the player character’s general damage output.

Gaining more hit-points obviously makes the player character more durable, though in practice, the player’s skill at preempting and dodging attacks in the bullet board matters more than having more hit-points.

“ACT”:

There is a category of actions which are lumped under the catch-all in-game term “Act”. These actions do not attack the targeted enemy, but rather have the player character doing something to convince the enemy to stand down, sap their will to fight, or just drop their guard.

These actions tend to be unique to the type of enemy which is being targeted, though they are universally silly. For example, in the case of the cleanliness-obsessed Woshua monster, the protagonist can request cleaning. Woshua happily obliges, after which some of its attacks become green-colored instead of the usual white, and green ones happen to heal the player character instead of hurting him/her.

Some of the actions are red herrings, however, i.e. leading to no significant progress towards wearing down the opposition. The description of the outcome of these actions does mention this, fortunately.

Anyway, the goal of “ACTing” is to erode the enemy’s eagerness to inflict harm on the player character. After an action or two which mollifies them, they generally stop attacking; there is also flavour text which describes this occurrence.

If the player does not intend to let the enemy live, this is a good moment to inflict harm of his/her doing. Incidentally, any attacks made when the enemy’s guard is down will do a lot of damage – as befitting such an act of treachery.

SPARING:

The other ulterior goal of dropping the guard or eroding the resolve of an enemy is to obtain the opportunity to grant it mercy. The player is notified of this opportunity by the change in the colour of the name of an enemy; by default, it is white, but changes to yellow (or one of a few other colours, depending on the player’s choice which is made early in a playthrough). Interestingly, some Monsters do try to yield when they are badly hurt, in which case the player can spare them or finish them off.

After sparing an enemy, his/her/its sprite changes to another one which is translucent and static. This is mainly for differentiation between having an enemy spared or having it dead; death causes a Monster to visibly disintegrate. Sparing enemies rewards the player with some gold (less than what he/she would get from killing them), but no EXP whatsoever. There is a reason to persist with such a strategy though, as will be described later.

FLEEING:

The alternative to fighting with Monsters or trying to appease/cajole them is to simply run away. This is not always possible, however. Sometimes, the option to flee is simply not there, and at other times, there is an RNG roll at work. If the player is successful at the fleeing attempt, the player’s heart comically grows legs and scampers away.

Conveniently, fleeing a battle still rewards the player with any EXP and/or money from spared or slain Monsters.

FIGHTING:

If the player chooses to be violent, there is what passes for “fighting” in this game. The player is shown a diagram of a slightly disturbing pattern which has symmetrical regions of different colours. There are also white vertical bars which are moving across the diagram.

The player’s general goal is to land the bars at the central region of the diagram. This guarantees hits which inflict considerable damage. Landing the bars anywhere else leads to attacks with sub-par damage. In the case of bars hitting the trailing regions, the attacks may even miss.

For better or worse, there are very few, if any, other elements which the player has to keep in mind when making attacks. One of these few elements is that different weapons may spawn different numbers of bars, and the bars may be spaced differently from each other.

COMMON MONSTERS:

There are Monsters which belong to specific species, i.e. there are some Monsters which look like each other, fight like each other and respond to the player character’s decisions in similar ways.

Amusingly though, the game appears to treat each species of Monsters like it is the same individual. There are even Monsters which have human names, like the mer-horse Aarons and anthropomorphic floor cleaners Woshuas. This can lead to some confusion about the narrative, especially among players who have not experienced RPGs with old and outdated text-generating scripts for combat encounters.

Generally, encounters with common Monsters occur randomly; the player character may be walking about and is suddenly accosted by previously unseen enemies. Obviously, if the player intends to get to somewhere, this occurrence can be annoyingly tedious.

However, after the player has dealt with the “main” monsters which act as the top adversary in a region of the Underworld, the random encounters are disabled, which help make backtracking less of a problem.

Interestingly, common Monsters may accost the player in pairs or trios. Their combinations depend on the locale that the protagonist is in; incidentally, they happen to be friends with each other. This can be seen in their statements about each other as the “fight” progresses. For example, the living mini-volcano Vulkin makes an amusing remark that it is alright for the sentient mini-plane Tsunderplane to shrink into a corner of the screen when it is spared.

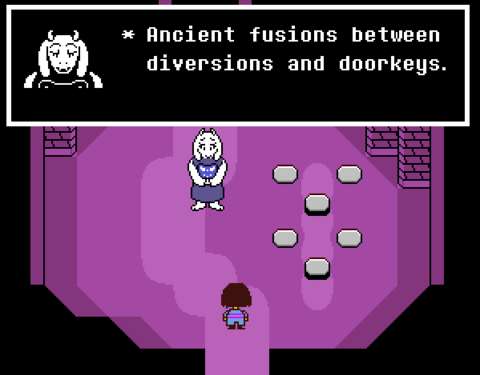

MAIN MONSTERS:

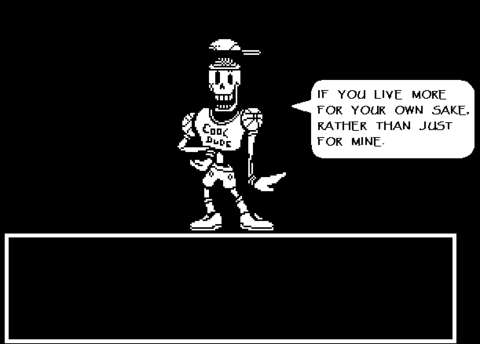

There are some Monsters who appear to be one of a kind, e.g. having sprites and names which are unique to them. These are most of the main characters in the game.

Most of them would be the protagonist’s adversaries, usually appearing at the end of a biome within the Underworld (to make use of a term which is usually used for sandbox games with procedurally-generated environments).

As to be expected of such singular opponents, they put up much tougher fights than common Monsters do. Incidentally, the fights with them also involve the aforementioned heart colours.

The main value of these characters are their personalities and regard for the player character. They have plenty of things to say about what the player character does. If the player happens to follow either of the two extreme playstyles, most of them exhibit facets of their character which the player would not otherwise see if the player had been pursuing a playstyle that is in between.

SHOPS:

There are “shops” in the Underworld where the player can buy items with GOLD. Most of them do not allow the player to sell anything however, despite the option being in the list of interactions which the player can make with the shopkeepers. There is just one shop that does buy the player’s things, but finding the shop requires some backtracking and going through a lot of silly and repetitive statements from the shopkeeper.

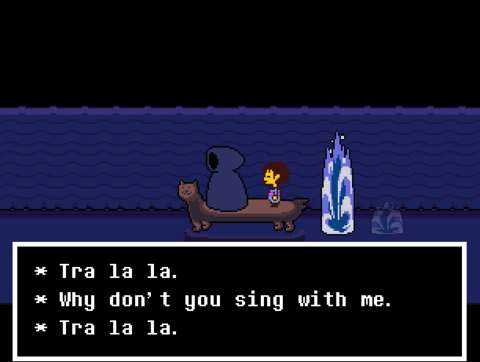

SHORTCUTS:

For most of the game, the player character is walking around on his/her two legs. This can become tedious, especially if the player wants to backtrack to earlier locations (likely to visit shops for resupplies). Fortunately, whenever the player reaches the other end of a region of the underworld, a shortcut to the starting place of the region will be revealed.

There are two kinds of shortcuts: the ferry and the lift. For half of the underground realm (which is connected together by a river), the ferry is the main shortcut method. The ferry’s operator is a mysterious person, who mutters seemingly irrelevant things during the ferry trips (which, strangely enough, always go west even though the destination may be to the east). Interestingly, the operator does utter a few things about a certain hidden character.

The lift is used for the second half of the game. It is a lot less entertaining than the ferry trip, however, though this is perhaps typical of elevator rides in video games.

SPECIAL CONTENT:

If the player has not been informed beforehand about certain special content in Undertale, the player would likely kill some Monsters and spare the rest, or vice versa. Doing so results in the “default” ending and its minor variations at the end of a playthrough. However, a couple of important characters drop hints about the special content.

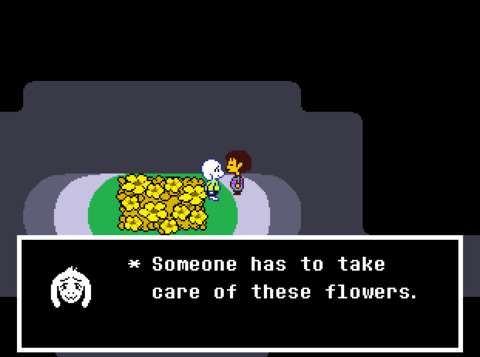

One sizable portion of the special content can be accessed by sparing each and every Monster, which also simultaneously befriends them (never mind that the player could have spared them by beating them to an inch of their lives). More of the Monsters’ personalities and inclinations would be revealed to the player, particularly those of the main Monsters, most of whom are nice people at heart. Furthermore, this path reveals the most about the game’s backstory, though unfortunately, not all of it.

The other portion can be experienced by doing the converse: killing each Monster and going on an extermination spree. A few of the main Monsters will reveal the true extent of their power in their attempts to stop the player character, and a couple of them happen to offer the most difficult bullet board fights in the game.

Unfortunately, this portion of the game seems to rush things along. Some of the more tedious gameplay segments which would have been played in a regular playthrough are thankfully removed in this playthrough, but some segments would seem incomplete even though there had been a clear change in circumstances.

For example, there could have been a fight against a certain robotic character which activated its supposedly most powerful form, but the fight would end before it even started. (In fact, a few fans who are skilled in the tools which were used to make the game happen to have designed a more complete fight for inclusion in a mod.)

Furthermore, although this portion of the special content does provide a few story tidbits which the other portion does not (especially about a certain other human character), it also raises more unanswered questions, like how a person who has gained much LOVE would be able to destroy reality.

VISUAL DESIGNS:

Unfortunately, Undertale’s visual designs could turn away some people, especially those who lack nostalgic memories of the transition from 8-bit to 16-bit in video game history.

Even a player who does not care much about cutting-edge graphics (such as yours truly) might notice that there are some disparities between the visual designs of this game. The most glaring disparities are the different amounts of effort which have gone into the bullet board screens and the overworld.

The overworld is mostly composed of static sprites and other artwork. If there is any significant animation to be seen in the overworld, it is in cutscenes. Otherwise, the most which the player would see are mouths opening when characters talk and luminosity changes for light sources.

On the other hand, the bullet board screen has far more animations than the overworld view. The Monsters are animated in this screen; their motions range from mere bobbing and fidgeting to silly dances and creepy changes in their faces. Some animations are even deliberately glitchy, such as the shaking face for a certain anthropomorphic feline Monster.

If there is any noticeable problem with the gameplay feature of sparing enemies, it is the sprites for enemies which have been spared. They look like they have been harmed, frightened or even killed, e.g. they have crosses for eyes or they are clearly bleeding.

Shopkeepers are only ever seen in their own shops, which are presented through display interfaces that are different from the overworld view and the bullet board screen. The visual designs seen here are more colourful than the rest of the game, though the animations and sprite frames of the shopkeepers are more comical than those seen in the bullet board screen. One of them, in particular, has become rather infamous among fans for her deliberately buggy facial expressions.

As for the visual designs of the characters, most of them are clearly intended to be bizarre, or even awkward (or both). For example, one of the silliest-looking characters is a skeleton with a terrible fashion sense. Players who have fond memories of the Mother/Earthbound IP would find them a little familiar, though they would be most familiar to people who follow Toby Fox’s works. (Incidentally, some of the Monster designs have been provided by his associates, such as Temmie Chang.)

WRITING & CHARACTER DESIGNS:

The main draw of the game, which compensates for its less-than-inviting visuals, is its writing. Prior to working on this game, Toby Fox has worked with other fiction creators, especially webcomic artists, as well as a considerable amount of work of his own devising. Undertale has benefited from his experience, because it has a gamut of tropes as well as the poking and lampshading of these tropes, such as the trope about random encounters with hostile things in JRPGs.

The characters are perhaps the best elements of the game. They are not entirely original characters, of course, but they also happen to be quite rare in video games. As mentioned already, most of the Monsters are nice people at heart, even though they have some rather aggressive and awkward ways of making friends of humans.

MISSING BACKSTORY:

Unfortunately, not all of the backstory is revealed. There are some gaps, a few of which can be glaring. For example, there is the matter of magicians among the humans, despite some characters having mentioned that humans have next to no gift for wielding magic. There is also almost nothing else about the humans in the world of Undertale, other than their general appearance.

Perhaps the most glaring gap in the story is the nature of the sealing barrier, which prevents the Monsters from returning to the surface. The barrier can only be broken by an incredibly powerful being, which supposedly can also wreck reality; how the Monsters came about this knowledge is not clear, other than a less-than-convincing tidbit about their researchers having studied this.

Perhaps there could have been content that has been held back for the sake of a sequel, but it might be just as well that Toby Fox do not have the time to fill those gaps.

“HARD MODE”:

There is a modified portion of game content which the player can access by providing a certain name at the start of a playthrough. This replaces the enemies in the prologue chapter with tougher versions of themselves (which incidentally appear much later in any other playthroughs). Obviously, this would have made for a much harder experience. Ultimately however, it is a short one – yet another example of Toby Fox’s whims.

SOUND DESIGNS:

Most of what the player would hear when playing Undertale is the music, which is composed by Toby Fox himself. Players who may have followed webcomics and other Internet fiction such as Homestuck might be familiar with his brand of electronic and chiptune music. For example, there are a handful of tracks which are unique when compared to the rest. The other tracks are variations of these, though the player would have to have a good ear in order to make out the basic tunes.

The composition of the soundtracks is matched to the thematic setting of the scenario which the player is experiencing – most of the time. There are some deliberately mismatched tracks, such as an urgent track which is played when all the player character needs to do is walk across a long but uneventful corridor. Observant players would notice that this is meant to convey hilarious awkwardness, of course.

Those that are matched to the scenarios which they are associated with happen to be quite memorable. For example, there is the playfully silly track which plays whenever Toby Fox’s counterpart in the game, the Annoying Dog, makes a fourth-wall-breaking remark about the limitation in a certain piece of gameplay content.

The rest of the sound designs are not as impressive though. There are no voice overs. When characters “talk”, the game resorts to the old JRPG tradition of having clicking noises accompany the scrawling of text. Granted, there are different tones for different characters, such as the rapid incomplete burps that are used for the shorter of two skeleton brothers, and the slightly grating crackles that are used for a nerdy Monster scientist, so Toby Fox was not entirely lazy in this matter. As for sound effects, they are little more than whimsical 16-bit audio clips, but again, at least there is variety in them.

KICKSTARTER BACKING & CREDITS:

Undertale has been made with not-insignificant crowd-funding; Toby Fox is already known to some backers, due to his work on some popular web fiction. The mention of crowd-funding would usually have only been given a passing remark in this author’s reviews.

However, it is worth noting here because of how the game presents the credits for Kickstarter backers. Instead of the typical and terribly boring long scrawl of names, the credits for them have been presented as one of the most difficult bullet board segments of the game, with an amusing reward for completing it without touching any of the names.

SUMMARY:

Undertale has some lost opportunities for more complex gameplay, specifically its limited use of the heart colours. Most of its story is well-written, but there are unexplained gaps in the backstories concerning the humans in the world of Undertale, and unanswered doubts and questions about the endings. There is also noticeable contrast between the effort that has been invested in the overworld visual designs and those in the bullet board screens.

Nevertheless, Undertale is a surprisingly amusing story with plenty of endearingly bizarre and inane characters. Coupled with very catchy music, this product of Toby Fox is far, far from a waste of time.