INTRO:

There had been quite a number of puzzle games that involves the manipulation of gravity and momentum. In the indie scene, there are examples like And Yet It Moves; in the big-name scene, Portal is an obvious exemplar. As such, the bar for such games has been raised very high. The Bridge does not reach that bar, unfortunately.

PREMISE:

The game is presumably a pseudo-autobiography of a post-Renaissance scientist; the setting of the game is not entirely clear about which real-world that it is based on. However, ultimately, it is not relevant because there are a lot of surreal things that happen throughout the game.

After some finagling around with the direction of gravity, the scientist, which is the player character, is woken up by falling apple; this is of course a reference to Isaac Newton, which is represented as a character in the game. The scientist, named Escher, goes into what is presumably his house. His house turns out to be a hub of sorts for pocket dimensions, many of which have mind-bending geometries.

For whatever reason, he has to go through each pocket dimension, while the player reads his monologues on the retracing of his journey to discover the secrets of reality.

It is here where the narrative becomes open to speculation. Escher could be becoming crazy, or his research has resulted in rather disastrous consequences. Even after the player plays the “Mirrored

puzzles, there is much left to interpret.

PLAYER CHARACTER:

The player character is the aforementioned Escher. Followers of puzzle-solving/platforming indie games might find him to be terribly slow – clumsy even.

He trots around at a leisurely place; there does not seem to be any means of making him run, much less sprint. He maintains this pace, even if there is an incoming hazard that can kill him. Furthermore, he skids down slopes quite readily, if it is angled any more than 30 degrees. Speaking of slopes, he climbs up them at an even slower pace.

His relative lack of alacrity compared to the protagonists of other indie puzzle platformers can seem frustrating, especially when it is quite easy to have him killed.

TIME REWIND:

The game compensates for the player character’s mediocrity with a time rewind feature. The player can rewind at any time, including when the player character has been killed.

Other than the obvious limit that is the starting moment of every level, there seems to be no limit to how much rewinding can be made. This suggests that the game continuously records the player’s actions and the movements of non-static things. Fortunately, the game’s coding is quite efficient in this regard; its memory usage never seems to bloat.

Having to use the rewind feature is actually an indicator that the player is doing things wrong, and should do something else. In the non-Mirrored levels, the alternatives are much easier to figure out; the level layouts and the hazards in them are not too complicated.

ROTATING WORLD:

For whatever reason, the player can rotate the entire level with the press of a button. This is a smooth kind of rotation, unlike the rotations of 90-degrees in And Yet It Moves. This is just as well, because some of the puzzles can be quite exacting in the angling of the levels.

There are two speeds of rotation, depending on how fast the player presses the control input and how long the player held it down. Fast presses causes a fast but short rotation, while holding the control input down causes the rotation to kick to the higher gear. Understanding this is necessary in order to solve the puzzles in the Mirrored levels.

Incidentally, the abovementioned controls are much better performed with controllers that have analog sticks, for better or worse (certainly worse for players who insist on just using the keyboard).

GRAVITY:

The main reason to rotate levels is to make things fall or roll down slopes, whichever is expedient. However, gravity does not always act the same way on everything. There are inanimate objects with reversed responses to gravity; they have splotchy textures that mark them out from other objects with normal responses.

Due to the surreal level designs, there is not a fast and easy way to predict the movement of non-static objects, unless their movements are already heavily constrained like the sliding plates. The player will need to start every unfamiliar level by rotating them around to observe the motion of objects. This can give an impression of frequent trial and error, but trial and error appears to be very much the theme of the game; the narrative implies this too.

LEVEL BOUNDARIES:

Some of the easier levels have boundaries that prevent the player character and unsecured objects from floating out into the void. The more difficult ones do not. Having said things float away off-screen is a game-over; the player will need to reverse time to prevent this from happening.

DOORS:

The player character is “sketched” into existence in a level. In order to advance in the game, the player character has to go through a door, of which every level has one. This simple goal is easier said than done of course. The door is often out of immediate reach, requiring the player to overcome obstacles in the way.

LOCKS:

A door may also be locked, which bars progress until the lock has been removed. A locked door is unlocked through one of two ways: keys, or switches.

KEYS:

Some levels spawn keys; these are guarantees that the doors, or something important to the solution of the puzzle, will be locked. Having the player character come into contact with the keys causes the locks to be unlocked.

A key may be drawn into a level as a loose key. In this case, it can slide and clink around, possibly even off-screen if the player is not careful. Otherwise, it is chained to something. In this case, the player needs to rotate the level in order to have the key swung to some place that the player character can reach, or to coincide with the player character’s trajectory if he is falling (especially in the Mirrored levels).

SWITCHES:

Some levels have pressure switches. These may be linked to locks or vortices (more on these later). Having them pressed down either activates or deactiveates locks or vortices, whichever applicable. The switches have to be activated by placing something suitably heavy on them; this can be the player character, or one of the large Menaces (more on these later).

Indeed, many puzzles require the player to manipulate the movement of objects such that they land or roll onto the switches and depress them. Some of these puzzles can be particularly finicky though.

VORTICES:

Vortices appear in some levels; they can suck in and trap anything in them indefinitely. If there are no switches that control them, the vortices act as dead-end traps; if anything that is critical to a solution gets sucked into them, the player is stumped. If there are such switches, they can be used to trap Menace balls or prevent the player character from being moved by gravity.

MENACES:

Menaces are introduced a short while into the game. They appear as spheres with hideous faces and their presence is clearly acknowledged by the protagonist. They cannot move on their own, but they are often in the way and kill the player character outright if he comes into contact with them.

There are two sizes of Menaces. The large one will be the most ubiquitous hazard that the player encounters; much of the game is about bypassing them. The small one is rarely encountered as a hazard in puzzles. Rather, it is often contained in a compartment. It responds to level rotation and gravity changes in a much faster manner than the large Menace, so it can be used to estimate what would happen to the latter, if a large Menace is in the level.

GREY & WHITE:

There are levels with devices that change the shading of the player character. The default canonical shading – which is used for most official artwork – is called “Grey” in-game. The other shading is called “White”; the player character has much of the details for his sprite removed.

Incidentally, there are other things with such shadings. This visual difference is used to indicate the objects that the player character can interact with. For example, if the player character is currently “White”, he can only interact with objects that have their details similarly scrubbed.

Puzzles with this gameplay element are perhaps the most laborious of the lot, because they require a lot of backtracking.

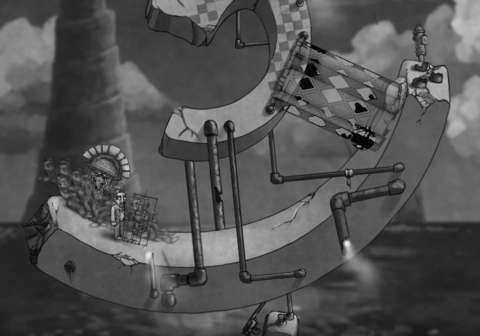

THE VEIL:

The last puzzle element that is introduced is the “veil”. It is represented as a curtain with a translucent argyle texture. The player character can walk behind it and thereafter, the effects of level rotation change.

For example, walking into a field in one level might apply the effects of level rotation to one object that has been marked with splotchy textures. The other objects in the level are not affected.

The veil also affects the gravity of the player character. Specifically, whatever effects that gravity has on the player character when he goes behind the veil is retained; if he is falling, he falls across the veil, for example.

The objects that are affected by veils are often needed to control the movement of the other objects. For example, a plate that is manipulated by a veil can be used to sequester a Menace into a section of a level.

Furthermore, there is a type of veil that simply acts as a trap of sorts for the player character; it prevents the player from rotating the level. The curtain that represents this kind of veil happens to lack dark-shaded diamonds in its patterns.

MIRRORED LEVELS:

After completing the default set of levels, the player advances to the “Mirrored” levels. There is a darker undertone to the narrative of these. The protagonist’s statements are grimmer and often paranoid. The artwork of the levels also has a winding streak of dark stains.

These levels, as their names suggest, are the horizontally reversed versions of the levels in the default set. However, there are also more complications, such as the presence of more Menaces and a few additional gameplay elements.

The solutions to most, if not all, of these levels require the management of the momentum of movable objects, especially Menaces. There is considerable trial and error, furtive and furious presses of the control input for rotation and plenty of rewinding.

The reward for the player’s tenacity in putting up with this gameplay is the protagonist’s increasingly desperate monologue and a few disturbing changes to the hallways of the Mirrored version of his home. Some players might find the player character’s spiral into madness entertaining, but others that have experienced stories about the loss of sanity would find this par-for-the-course at best.

The Mirrored levels also test the player’s familiarity with the gameplay. For example, a chain that is long enough to be hanging off-screen could have a key or a Menace at the end. Players who had stopped playing the game for a while might take some time to recall this, and they might be frustrated by how the inertia of the long chain can greatly complicate their attempts at solutions.

TOGGLES:

The Mirrored levels introduce toggles. These toggles come in the form of numbered doors. ‘Using’ the toggles switches objects from one plane of existence to another. Regardless of which plane that they are in, objects will still be affected by gravity. With that in mind, the presence of toggles means that the player must manipulate the level such that the objects can be moved around without getting in each other’s way.

MULTIPLE PLAYER CHARACTERS:

Some of the Mirrored levels have two player characters, whose actions are perfectly synchronous. Of course, veterans of puzzle platformers would know that this is a matter of managing the movements of the two player characters, typically by restraining the movement of one while having the other move around. The two player characters cannot come into contact with each other, though such a gameplay element is hardly new anyway in the history of puzzle platformers.

VISUAL DESIGNS:

The player is almost always shown the entirety of a level. This is a good design decision, as long as the levels are not too large. Yet, there are a few that are large enough that when the camera zoomed out, the player character and other non-static things are reduced to small sprites that can almost blend into the rest of the level. There are also large levels where the camera does not zoom out. This is not an issue if there are no hazards off-screen, but at least one of the Mirrored levels have these.

Almost all of the visuals are in black and white. Dark shading, heavy hatching and intricate details are used for contrast. Animated textures are mainly used for objects with different responses to gravity, as mentioned earlier. For the most part, this makes for adequate contrast, if the camera is being accommodating.

There is some commendable attempt at introducing some notable traits in the character designs, such as the bulging eyes that lack pupils. Observant players might even notice the disparity between Escher’s 19th.-century looks and Isaac Newton’s 18th.-century appearance. Yet, the characters lack anything that gives them staying power in player’s memories. They are not charming enough to be endearing and the story is too surreal to encourage any empathy for the characters.

The levels and animations for the player character look convincingly like sketches. The most notable of these is the animation for drawing the player character into a level.

The artwork that is shown during the interludes between levels has much finer pencilling. There is much emphasis on the surreal appearance of the game in these.

Speaking of surreal appearance, many of the levels have boggling geometries. This is actually used in gameplay: a pillar that looks like it can be a floor or ceiling when it is rotated to another alignment does become a floor or a ceiling when it is rotated that way. (This is not the first game that uses such visual trickery though.)

SOUND DESIGNS:

There are no voice-overs to be heard. The only noises that the player character would make are his footsteps, his skidding down slopes and the billowing of his coat as he falls (though the sound clip for the billowing repeats so frequently to the point of being goofy).

The other sound effects are those emitted by movable objects. The rolling of the Menaces is one that the player would keep an ear open for, because many solutions require the player to know when they start rolling. Of course, there is also the unpleasant deep-bass ringing that occurs when the player character is too near to any of them.

Keys clink and chains rattle. Both of these sound clips inform the player when they have overcome their inertia and started moving.

The music is composed of only a few tracks. All of them are conservative, but they are not too dull either. On the other hand, listening to them outside of the game is a boring experience.

CONCLUSION:

The puzzles in The Bridge are mostly well-designed. Discovering the first few steps of many solutions requires careful observation and deduction, which is indeed the point of puzzle platforming games. However, the later, more challenging puzzles require the player to manage the momentum of moving objects as well, which can be troublesome and infuriating, even with the convenience of rewinding.

There had been plenty other indie puzzle platformers that look and sound energetic. Perhaps The Bridge is intended to be different, but its low-key presentation also happens to work against its theme of increasing madness and danger.

The Bridge is not a waste of time – but there are other indie puzzle platformers that are more worthwhile playing.