INTRO:

It would not be a far stretch to claim that there are game consumers who are jaded enough to consider most of the offerings from today’s game-makers to be old hat.

Yet, if there are indeed such people, it would be very hard for them to consider that Papers, Please (designed by Lukas Pope) can be lumped together with the “been there, done that”.

After all, there are not many games that claim to be a “document-checking thriller”, a phrase which in itself would already be an oxymoron. Yet, Papers, Please, with the narrative of its Story Mode, would deliver its promise, in addition to (mostly) effectively implemented gameplay which are rarely seen in other games.

(Note: Most of the review will be written with Story Mode in mind; Endless Mode gets its own section.)

PREMISE:

Being a professedly ardent fan of dystopian settings where freedom rights are afterthoughts, Lukas Pope has, unsurprisingly, set Papers, Please in a world where authoritarian governments rule and trust is scarce.

Interestingly, Lukas Pope has set the game in the fictitious world that he had created for his earlier games, namely Republia Times and 6 Degrees of Sabotage. However, compared to these earlier titles, which he made for one-off events, the backstory of Papers, Please is much more fleshed out in comparison.

Furthermore, the fictitious country that the game’s story takes place in is Arstotzka, a country that happens to be in the same (fictitiously) geographical region which Republia is in.

Anyway, the player character is an apparently adult male citizen of Arstotzka. He has been chosen via lottery to be the inspections officer at a new border checkpoint. This would not be much of an issue to the player character; in fact, it is a job that would feed and house his family. Unfortunately for him, this checkpoint occurs at a flashpoint region in between Arstotzka and its resentful neighbour, Kolechia.

Needless to say, trouble looms ahead for the inspections officer, who would have to decide which comes first: duty, conscience or naïveté. That any decision comes with undesirable consequences doesn’t make things easier.

BEFORE STARTING WORK:

The game starts itself off by having what appears to be the player character walking into his booth. The player can do nothing meanwhile, but he is just a few steps away so this is a minor annoyance at worst.

Once the player character is in the booth, the player can check the stuff in the booth, most of which are important.

More importantly, this is the only time before the start of the working day when the player has the opportunity to leisurely check the rules that he/she has to follow. This is also the time to check news on the development of the backstory. The clock that indicates the operating time will not start until the player clicks on the loudspeaker above the booth.

(However, clicking on the loudspeaker is also associated with an issue of user-friendliness, as will be elaborated later.)

RULEBOOK:

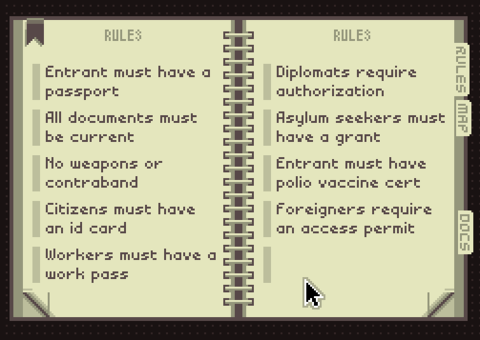

The most important document in the booth is the rulebook. It even has its own convenient storage compartment in the booth (but the player is more than likely to keep the book out of it than inside it).

The rulebook contains text on the rules that the player must follow; these will be elaborated later. The rulebook also has pages that are dedicated to the geography of Arstotzka and its neighbours, detailing the provinces in their territory. Being the property of Arstotzka, it also has sections on the identity cards that are carried by its citizens.

Indeed, more pages will be added to the rulebook as the Story Mode progresses, reflecting the maturing (or convolution, depending on one’s point of view) of the bureaucratic processes at the checkpoint.

The rulebook ostensibly has to be viewed page by page, but fortunately there is a contextual tool that can be used to reset the currently viewed page in the rulebook to its table of contents. The table of contents in turn contain shortcuts to the sections that the player may need to look at.

Later, there are options that the player can purchase to add more shortcuts. These are tied to the system of booth upgrades, but this system is associated with an issue of user friendliness that will be described later.

BULLETIN:

The next important document is the bulletin, which is already on the booth’s desk by the time the player character walks in (strongly suggesting that someone is rummaging through the booth’s contents daily).

The bulletin imparts updates on the geopolitical status in the region, e.g. the ongoing relationship between Arstotzka and its neighbours. These political developments also happen to cause some temporary rules to be introduced. These temporary rules give a good impression that the backstory actually has an impact on the gameplay in Story mode and is not just an inconsequential decoration.

For much of the Story mode, the bulletin does not need to be referred to after the player has read what it has to offer and thus can be chucked back into its receptacle in the booth.

Eventually though, the bulletin does play into one of the gameplay elements, which will be described later.

AUDIO RECORD TRANSCRIPT:

Disturbingly enough, there is a device in the booth that can pick up conversations and recognize words perfectly before scribing them down into paperback transcript.

The audio record is generally only needed for double-checking the intent of the prospective entrant for entering Arstotzka. This is something that he/she will say when questioned by the player character right after he/she has entered the booth, which also happens to be the time when the player would be busying himself/herself with checking the documents that the entrant hands over.

Even if there are discrepancies between the entrants’ statements and their intentions as stated in their documents, the entrants simply retract their statements and correct themselves; this happens without fail. If the player fails to point out this discrepancy, the player is penalized.

This element of the game gives the impression that it was mainly intended for the convenience of players and is only a half-hearted gameplay feature. That the transcript resides just behind the panel that starts the interrogation processes reinforces this impression.

WEIGHT SCALE AND WALL RULER:

Less disturbing than the audio recorder are the scales that are built into the floor of the booth and the height ruler that is stencilled onto the wall behind the entrant.

The scale is not of much use early in the Story Mode. However, when shifty entrants with dubious things on their persons start to appear, the scale is put to use. The player only needs to simply compare the entrant’s current weight as depicted by the scale against his/her weight as stated in his/her papers (among the other kinds of frivolous information).

The height ruler is used to check the entrant’s stature. Although parallax error is indeed apparent in the game, the player needs to only consider the entrant’s height if it appears to be very far from his/her height as stated in his/her papers. Using the correlation mode can confirm the difference.

However, the current build of the game at this time of writing has a few rare incidents where the height of the entrant clearly mismatches with the height stated in his/her documents, but the game does not appear to notice this mismatch despite the player’s attempts to correlate them. This is likely due to a rare typo problem. Fortunately, the game does not penalize the player for letting the mismatch get through.

Discrepancies between the entrant’s stated height and weight and actual height and weight are not the end though, especially later in the story mode when the player must double-check his/her identity. This involves an identity-confirming step that will be described shortly.

Nevertheless, more experienced players would eventually learn that checking an entrant’s physical measurements are one of the best ways to quickly spot impostors. This lesson can be quite satisfying to pick up.

FINGER-PRINT CHECKING:

Whenever there is suspicion about an entrant’s identity, one of the player’s means to get to the bottom of this matter is checking finger-prints. Certain processes even mandate such a process.

Perhaps unsettlingly, Arstotzka’s Ministry of Admission has an extensive database of fingerprints that includes an entry on just about any possible entrant. Upon pressing the button to dispense an empty fingerprint slip, another slip containing the fingerprints of the alleged person is produced from the database as well.

The player hands the empty slip to the entrant, who will somehow fill it and then return it. The player then proceeds to cross-examine the finger-prints, and point out any discrepancy for further action.

To make things not so easy for the player, the printed slip of fingerprints from the database is not always cleanly printed, and the entrant may not have thoroughly smudged their fingerprints on the slip handed to them. Inexperienced players can be easily lured into making wrong decisions, but eventually, wiser players would learn to notice that when fingerprints are different, they are significantly and noticeably different.

SCANNER:

The most surprising tool that the booth has is some kind of scanner that can see past entrants’ clothes and take photos of them. Of course, this has been featured in many trailers and the demo before this game was released, but considering how old and rustic the other technology in the booth is, this scanner can seem out of place.

(For those who have a modicum of scientific knowledge, the scanner may be a mid-infrared or near-infrared scanner, but the elaboration of such a supposition is beyond the scope of this review.)

Anyway, the scanner is usually available for use when suspicions arise over the person’s weight and gender. The scanner is a tool that takes many precious seconds to use, so wilier players would learn to avoid its use whenever they can, or at least prioritize checking details that may lead to the use of the scanner.

After the scanner does its work, the player gets a photo of the body of the entrant sans clothes, as well as any objects that happen to be opaque to the scanner too.

Generally, the presence of any such object is an immediate breach of the rules of entry. The game could have been more complex if not all of such things are outright proof of malfeasance, but perhaps this simplicity was for the better, considering the precious seconds that the scanner takes away.

ENTRANT’S DOCUMENTS:

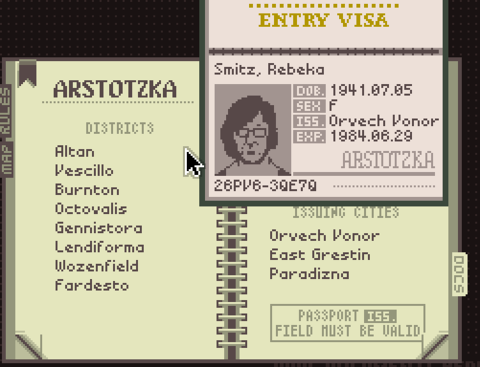

The most daunting gameplay-related task in the game is the need to check the titular papers that entrants produce. As the player progresses in the Story Mode, the types of papers only increase.

Ironically, this makes processing entrants that are eligible for entry tougher, but it makes spotting entrants whose papers are not in order a lot easier. It is perhaps this subtle change in the gameplay experience that makes Papers, Please more enjoyable than its pedantic gameplay suggests.

There may be several types of documents, but many of them have the same types of information; an astute player would notice this. Cross-referencing these types of information, namely passport numbers and names, is the main way to spot discrepancies in identities.

One of the quickest ways to know which entrant is to be denied is to check the expiry dates on their documents; a single discrepancy is enough to reject an entrant.

Soon, the player will learn many “quick” ways to spot problematic entrants. Which one the player would pick first becomes a matter of preference, as well as luck. After all, a player can go through a list of “quick” ways before finding a discrepancy, but only after having spent some time already.

FACTOR OF LUCK:

Having said all of the above, it should be apparent by now that the game does have luck as one of the factors that determine the player’s performance.

As an illustrative example, the game could somehow pile a consecutive bunch of entrants with discrepancies that require the use of long processes, such as finger-print checking and scanning. Even if the player has adapted checking techniques that prioritize the checking of details which in turn lead to these processes so that they may be done while the player checks other details in the meantime, the player will still be expending many seconds which would not have been spent in the case of other kinds of entrants.

The player might also get lucky, encountering a string of entrants with expired documents; these can be sent away with the mere stamping of red ink.

The game does try to distribute the types of entrants as evenly as it can, in order for the player to get a balanced permutation of entrants. Yet, this is in itself a matter of chance as well.

DESK SPACE:

One of the most tedious yet most satisfying elements of the gameplay is the limited desk space that the player has to work with. This may seem contrived and perhaps even unbelievable, because the level of zoom on the documents on the player character’s desk may suggest that he is not using it in its entirety.

Indeed, the player will be shifting a lot of documents about, wasting precious seconds. Yet, players that have an ergonomic knack for planning would eventually figure out how to scrounge for space, obscuring unimportant parts of documents while keeping the important sections visible.

If there is a complaint to be had, it is a minor one: shifting documents around could have been a lot more convenient if there is an option to maintain the overlapping views of the documents. By default, any document which the player is moving around is moved to the top, obscuring the rest. If this document could be moved around while the others remain above it or under it, scrimping for space would have been a lot easier.

STAMPING & DETAINING:

For all the kinds of entrants whom the player would meet, there are ultimately two actions which determine how the player would deal with them: stamping ink on the entrants’ passports, or calling guards to detain uncooperative and/or suspicious entrants.

(Amusingly, there is a slip that can be used in place of a missing passport, but it may only be used for denials only.)

The astute player may notice that there are some cases where the player can choose to either arrest an entrant or stamp red ink on an entrant’s passport. These happen for discrepancies such as mismatching information in between different pieces of documentation. As long as the player rejects the entrant in any way, he/she is not penalized.

Early on in the Story Mode, wiser players would go for the stamping of red ink, which is a lot quicker. However, once the documentation needs start to pile up and the story introduces an incentive to detain suspicious entrants, arrests are a lot more efficient in dealing with entrants as quickly as possible.

Such subtle changes in the gameplay can make Paper’s Please more enjoyable than its clerical excesses may suggest.

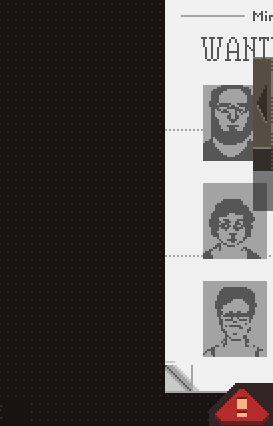

There are some cases in which arrests must be performed in lieu of anything else. There are a few entrants who will be marked as “criminals” in the bulletin, and there will be a rule which requires the player to identify them and arrest them.

INSPECTION MODE:

One of the silliest features in the game is the tool to make correlations and thus identify discrepancies in an entrant’s papers. Upon activation of the tool, the screen takes on a different visual filter that highlights things that the player wants to check and correlate with other things.

Its technical description is not what makes this tool silly, but rather its visual and audio designs. Dotted lines are traced from one thing to another, to the accompaniment of beeping noises. The player also wastes a bit of time waiting for the lines to be traced and the text for the results of the correlation to appear (though this is a process that occurs quickly).

The player is not informed about the game alternating between the two ends of a line when the player redirects the correlation. This can result in some confusion among new players that are not aware of this.

Alternatively, the player can reset the line by going out of inspection mode and back again, but of course this takes time.

END OF WORKING DAYS:

The end of every working day in the Story Mode occurs when the clock strikes what appears to be 6.00 pm. However, the player is allowed to drag the day a bit in order to process the last entrant.

(Previously, in earlier builds of the game, the processing of this last entrant does not count towards the player’s daily salary, but this has since been rectified in updates.)

After having the player character gone home to his family, the player is informed about the conditions of his family. At the risk of sounding rather cavalier, keeping all family members alive is not necessary but ensuring that at least one survives is required; apparently, the nation of Arstotzka looks down on proletariats who cannot maintain families.

Assuming that the player can still continue the game, the player then decides what provisions to give to the family for the next day. The consequences of the player’s decisions only become clear at the end of the next day (which can include some unpleasant surprises).

Some story-related decisions also come into play at the intervals between days. To elaborate on these would be to include spoilers in the review, but it should suffice to say that few good things come from acting out of the norm; the game will take any chance to remind the player that it has dystopian settings and trust is but another form of naïveté.

FAMILY MEMBERS & UPKEEP:

The conditions of family members mainly depend on whether they have had heating and food in the previous day (or days) or not. Foot and heat for family members cost money; this cost is counted for every member that is still alive.

Particularly ruthless players can deliberately have some family members die in order to keep costs low. Other than this, the player can withhold food or heat in alternating days, which will not affect the tougher family members too much.

The only exception is the player character’s sickly son. The son, even with adequate food and heating, still has a considerable chance of falling ill. Such an occurrence requires the player to spend money on medicine for the son, lest he simply dies in the following days.

The player character is of course supporting his family through his job at the checkpoint. However, he does not get a minimum salary stipend, or even a basic amount. Instead, his salary depends on how many entrants that the player has processed correctly. This means that the player must be as efficient and effective as humanly possible in order for the player character’s family to scrape by and still have some savings left after having made the deductions for food, heating and the unavoidable rent.

The player can have the family moving into higher grade abodes. This appears to mainly affect the rent and heating rates. There is no other effect, which can be a bit disappointing.

The player character’s family is intended to tug at the player’s conscience. They may be characters that are only ever encountered in the form of words, but there are some story developments that concern them and they are associated with some options of expenditure, not least of which is medicine for the sickly son.

USER FRIENDLINESS ISSUES:

Although Lukas Pope may have covered new ground, or treaded the metaphorical path less taken, in terms of gameplay designs with his self-proclaimed “document-checking thriller”, he has some notions about user-friendliness that not everyone who likes the game would be pleased about.

In the demo version of the game, the hotkeys for drawing out and retracting the stamp sliders and for toggling the inspection mode were mentioned to the player, as well as being available right from the start.

In the actual game, these conveniences are hidden behind the gameplay mechanism of so-called “booth upgrades”, which the player must purchase with the money that has been earned from the player character’s hard work.

This can seem disingenuous to some people who had been following the development of the game, especially if they had very different expectations of what “booth upgrades” would be.

There are also a few other design decisions that may not seem conducive to user-friendliness. An example of this is the need to click on the loudspeaker above the booth.

One of the purposes of this action, which is to start the clock from 6.00 am to the end of the day, had been described earlier; this is a lot more acceptable.

Unfortunately, afterwards, the player must click on the loudspeaker to get the next entrant into the booth after having processed the previous one. There is no clear benefit to delaying the next entrant, so it can seem quite a hassle to have to do this.

The other game designs, such as shuffling documents around on the player’s limited desk space, at least have limitations and tedium that are believable and understandable.

STORY-RELATED EVENTS:

All of the abovementioned gameplay designs would have been terribly dull and repetitive if not for the considerable number of special incidents throughout the experience of the Story Mode.

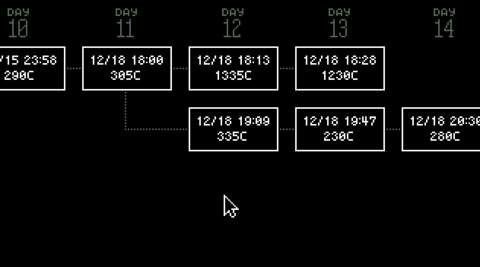

These events often require the player to make a decision, which in turn can lead to different outcomes and ultimately one of the 20 endings for the game. To help the curious player in finding all of them, the game has a convenient save-game system that shows the branching of the storyline. The game will not show a log of what incidents have occurred though.

On certain days, there are special characters and events that shake up the monotony of the player character’s workday. The most subtle of these are none other than the first entrant, which usually comes in with a discrepancy in his/her papers that reflect the importance of new rules that had been imposed on the checkpoint.

Then, there are notable individuals that come to the checkpoint to impart ominous warnings or reminders before simply stepping out. These persons are involved in a plotline that concerns simmering tensions between Arstotzka and its neighbour Kolechia, as well as insurrection from within.

Next, there are individuals who bring trouble to the checkpoints – trouble that is usually followed by mini-games with outcomes which have significant consequences.

For example, there is a very simple mini-game, in which another character even provides the solution. If the player succeeds, there is a small amount of money to be gained. If the player fails, he/she gets a straight game-over and is given the ignominious reward of one of the game’s 20 endings.

The most common mini-game though is the one that requires the player to unlock a gun cabinet and actually shoot certain individuals. This can feel very out of place, but still appropriate if one considers the settings of the game’s story. To elaborate more would be to invite spoilers into this review, but it should suffice to say that the player will have to shoot someone.

Next, there are people who come to the checkpoint with the assumption that the player character can be bribed. It is up to the player to decide whether the player character is corruptible or not (though there are consequences to any decision).

However, the righteous player does not always get the choice to reject “gifts”. Certain morally dubious entrants drop them onto the booth counter, but not all of the “gifts”, especially cash, can be returned. This is perhaps an oversight on Lukas Pope’s part.

Still, these incidents would teach the player that small wads of cash can be pocketed without incurring any suspicion.

Finally, there are characters that come to the booth with sob stories, begging to be admitted into Arstotzka. These cases pit the player’s conscience against fear of reprisals, because more often than not, these individuals come with their papers out of order. Some other characters even beg for someone else to be denied entry; this some other person, of course, happens to have his/her papers in order.

In the Steam version of the game, there are a handful of achievements which are associated with the player’s decisions in handling these encounters.

Amusingly, being indifferent to the events in the Story Mode and being a stickler to rules is the only way to unlock the other gameplay mode for Papers, Please.

ENDLESS MODE:

The Endless Mode is the player’s reward for being apathetic to the occurrences in the Story Mode, and it is an amusingly ironic one that would have the player realizing how boring the game can be outside of its story.

In Endless Mode, the player engages in one-off sessions that can only end in failure for the player, after either quitting or after making one too many mistakes (or being too slow).

The most interesting element in Endless Mode – and there are few interesting elements that the player has not seen in the Story Mode already – is the combinations of document complexities and session types that the player can make.

There are three session types, each of would test the techniques that the player has developed over the course of the Story Mode.

“Timed” gives the player only 10 real minutes to process as many entrants as possible. The player can attempt to extend this time by detaining entrants whenever possible, but the extension of 5 seconds is more intended to compensate for the arrest animations than as a bonus. Moreover, any mistake costs the player 30 seconds, deducted away from the timer (which appears on one of the walls of the checkpoint).

“Perfection”, as its name would suggest already, requires the player to correctly process any entrant. Time is also a factor in the accumulation of the player’s score.

“Endurance” is meant for more laid-back players. There is no time limit and no immediate game-over. Instead, how long the session can stretch is the game’s measure of the player’s perseverance (the name of the session type would suggest this already). The player must build and maintain a score, which is reduced whenever the player makes a mistake. The penalties increase in severity for each consecutive mistake.

Endurance is the only Endless Mode session type to live up to the name of the game mode. It can never end if the player is careful enough to process entrants correctly.

Eventually, Endless Mode would reveal the tedium of the game’s regular gameplay. Without the special events in the Story Mode, Endless Mode is a lot less entertaining and can become tiresome, especially for players that have little inclination to pursue high scores.

VISUAL DESIGNS:

Papers, Please is a game that makes use of pixel art. Fortunately, since it is a game about checking documents, the game does not resort to grainy shapes for textual characters. Most of the text can be read easily, with the exception of the finger-print database print-outs, which had been mentioned earlier.

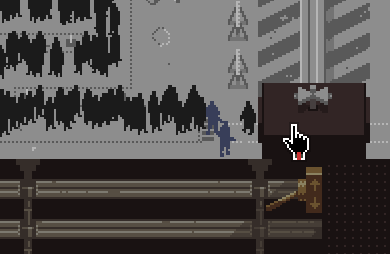

For everything else though, typical pixel art is used. This can be best seen in the non-descript, vaguely humanoid sprites that pass as people on the upper part of the screen, which shows the checkpoint and its immediate surroundings.

For the purpose of creating believable looks for entrants, the game makes use of a system that creates permutations of faces, heads and shoulders from a database of sprites. The results are not just for cosmetic purposes and actually come into gameplay when the player must double-check the looks of entrants.

(There are also some hilariously rude descriptions of the looks of entrants.)

Although the game goes out of its way to randomize the looks of entrants (except for a few story-related characters), there are practically no animations for when entrants hand over their documents; these simply slip into view on the booth’s counter.

Amusingly though, the player returns the documents to entrants by lifting and dropping them out over the counter. Having this occur in real-life would be a silly occurrence, not to mention rudeness on the part of the booth officer. Nonetheless, this limitation can be chalked up to the game’s simple graphics.

The booth has window blinds, which are essentially additional sprites that can come down to obscure the entrant or come up to ease processing. At best, window blinds are merely there for cosmetic purposes. That they are drawn down after the player has ordered the detainment of a suspect can be annoying though, because the player will have to waste a heartbeat to retract it. Still, this is a very minor complaint because it does not affect gameplay too much.

Interestingly, for an indie game developer, Lukas Pope has included options to have the aforementioned scanner produce completely nude pictures of entrants or have them wearing opaque underwear. Considering that most other indie game-makers would not censor themselves so readily as to provide similar options, this is an amusing feature to highlight (as is another thing about the game which would be described later).

Passports of different nations have covers that are coloured differently; this is useful for when there are rules pertaining to entrants of different nationalities (these only occur in the Story Mode).

However, most of the other kinds of documents do not have colours which are of such high contrast. Most of them are, perhaps expectedly, various shades of beige and white. Only the different sizes of the documents and the patterns of the printed text on them help in differentiating between them while they are on the booth counter. When they are on the desk, they are a bit easier to work with, but of course the player must scrimp for space.

HARDWARE/SOFTWARE REQUIREMENTS:

One of the most surprising things about Papers, Please is its need for comparatively present-day graphical technologies. Considering that most of the game’s graphical designs are pixel art, this can seem strange, even misleading.

However, the reason for this requirement might lie in the design of the booth screen. There are at least three independently animated panels in the booth screen, but the user interface must allow the player’s mouse cursor (be it an arrow, hand or item that the player has picked up) to transition between the three panels smoothly.

In the case of the panels for the counter and the desk, items that have been picked up have to transition smoothly between their form that is used on the booth counter and their form that appears when they are placed on the desk. This is not likely a graphical transition that is easy to implement.

SOUND DESIGNS:

Although much of the game had been made by Lukas Pope himself, he has used sound assets that are created by other people.

Most of these sound assets are the noises which are associated with the documents, such as the scraping of paper against paper, the turning of pages and the closing of books. The lack of animations for these occurrences does make them less believable though, but Papers, Please was never intended for people who have preferences for high-definition graphics and sophisticated audio.

There are no legible voice-overs whatsoever; any conversation is carried out with speech bubbles. There are some illegible utterances, such as the gibberish that the player character speaks into the loudspeaker above the booth, but they are taken from a small library of sound clips.

There are only a few music soundtracks in the game, and even then, these play only in the main menus and the endings. Perhaps such scarcity of melodious sounds is for the better, because it increases the atmosphere of oppression that the game is trying to project.

OTHER MENTIONS:

One of the ongoing updates to the game happens to be one of its most hilarious aspects. It also highlights the risks which developers take on when they unwittingly receive input from fans of the game while it was being developed.

In the launch version of the game, there were many names with dubious meanings in the database of names that are randomly applied on entrants’ documents. (As a side note, surnames and first names change places in the entrants’ passports regularly.)

Examples include names that are actually Romanized composites of expletives in European languages, and slightly altered names of copyrighted fictional characters and real-world celebrities who happen to have trademarked their name.

Some players probably do not realize this when he/she is playing the game, but these hilarities – or offensiveness, depending on one’s point of view – would be apparent upon reading the patch notes for updates.

Just after the launch of the game, there were a considerable number of bugs, which Lukas Pope acted quickly on. That most of the updates by far are fixes instead of more valuable additions can be a bit disappointing, but at least one of the latest updates included more language options.

CONCLUSION:

Frankly speaking, the gameplay in Papers, Please is actually quite repetitive and dull as can be expected of what is ultimately manual and clerical busywork. Even if it is a very rare kind of gameplay in video games (there had been games with bureaucratic drudgery before), it would have provided scarce fun – and certainly not of the exciting sort – on its own. The game’s Endless Mode is certainly evident of that.

However, the Story Mode in Papers, Please moulds what would have been boring gameplay into an engaging story of a commoner trying to make ends meet for himself and his family in a dystopian country wrecked with oppression and strife. It is a rare combination if one is to consider that such settings are often used in action-packed games. Therefore, that Papers, Please would think outside the box for the use of such settings makes for a very refreshing difference.