INTRO:

When they do appear in video games, luchadores often play few roles other than just being another contender in an arena. The over-engineered mysticism about them is often missing in such games, making them little more than wrestling games with a Latino bent.

Guacamelee! is not one such game, fortunately. It would portray them as not only ring-fighters with outrageous fashion-sense, but also as folk heroes with more than a bit of magic on their side. Better yet, entertaining presentation is not the only thing which this game – designed by indie developer Drinkbox – offers. It also boasts a repertoire of gameplay elements, which while quite standard-fare on their own, would come together in a surprisingly sophisticated way.

PREMISE:

Juan is a lonesome agave farmer (and possibly a drunkard too), living outside the town of Pueblucho. Due to reasons which would only be revealed later in the game, Juan wanted to be a luchador, but could not. There was also a fling between him and the President’s daughter, but that did not work out too well either.

Juan turned into a taciturn recluse, and it would seem that his life would be composed of nothing more than growing agave, churning the plants and distilling tequila from them.

However, as fickle fate would have it, Pueblucho comes under attack by the undead, heralding a dark time where the Land of the Dead would merge with the mortal realm. In an attempt to rescue his old flame, Juan was slain. However, death would not be the end of him, because he would somehow come across a magical mask in the Land of the Dead that he is to wear.

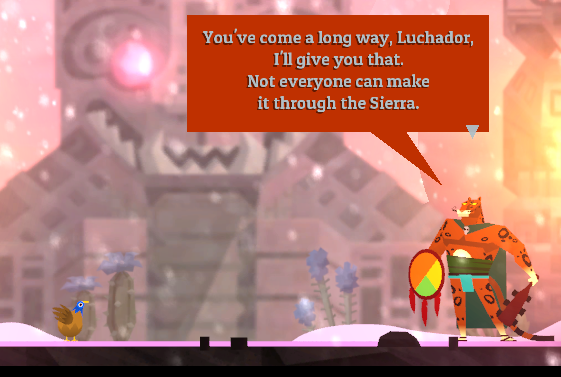

He returns to life, now a hulking luchador, albeit a neophyte. He would grow stronger and have many amusing adventures along the way to saving the damsel in distress.

With all that said, Guacamelee’s story does take a lot of liberty with Mexican folklore, which it purportedly took inspiration from. Luchadors are super-heroes in Guacamelee’s world, often empowered by ancient South American magic and trained by giant chickens and a goat-man sage with a lust for old mothers.

The settings are silly, but not too outrageous as to take the limelight away from the game’s strongest aspect: its gameplay.

PUERILE EXPERIENCE:

As to be expected of a game where the protagonist is a luchador, the player can expect to be doing a lot of brawling. Either player character – Juan or Tostada (who fights alongside Juan in co-op mode or can be switched to via the costume mechanism) – can punch, kick, throw, head-butt or stomp enemies, among other more complex moves which the game will gradually introduce.

Fortunately, the game rewards skillful play; good players who are familiar with the gameplay elements of beat-‘em-ups or action-platformers can blow through the opposition quickly and, more importantly, with satisfying efficiency.

Interestingly, some fighting moves will be used for the platforming sequences of the game as well. The result is a bit awkward to look at; after all, not every game with platforming in it requires the player character to do a leaping uppercut onto a platform or do a dashing strike to move horizontal distances. Still, the experience is surprisingly entertaining, especially when the game places an enemy at the end of a platforming stretch, only to have it struck down by the last platforming move.

RESPAWNING ENEMIES & BYPASSING THEM:

When the player character enters a new area, the game customarily locks the player character into rooms, forcing the player to deal with waves of enemies which spawn in.

When the player character returns to a room which has already been cleared earlier, enemies respawn. However, the game does not lock the player character into the room again; this is a major difference between Guacamelee and other action-platformers who resort to such padding. If the player does not wish to spend time engaging these enemies, they can be bypassed thanks to the player character’s incredible agility.

PLATFORMING:

In addition to fighting, the player character will also be doing a lot of jumping, including onto and off vertical faces, floating platforms and moving platforms, etc. The level designs for platforming sequences would not surprise a veteran of platforming games.

What would at least amuse said veteran though is the aforementioned use of fighting moves as platforming aids. This is pointed out to the player early on, after the player character obtains the uppercut move and has to get that little extra vertical boost to get onto a platform. Later on in the game, the game is silent on such matters; instead, it places obstacles in the player’s path which can only be overcome by using a recently-obtained move.

Such use of fighting moves as platforming aid is quite entertaining and satisfactorily refreshing (at least to this jaded reviewer), especially when one is already tired of the usual staples such as double-jumping,

(Speaking of which, there is double-jumping in the game.)

GAINING MOVES:

Gaining moves is a mandatory task in order to progress in the game. There is a side-story of sorts about a certain goat-man character who hides luchador-related powers in statues, for whatever reason. Coincidentally, they happen to be in the player character’s path as he goes on his quest to save the world, and it so happens that smashing those statues is an easy way for a luchador to power up.

After a humorous scolding by the very irritated goat-man, the player is informed of how to make use of the just-obtained power. Conveniently, there is always an obstacle course close-by for the player to test the power with.

HEALTH & INVINCIBILITY FRAMES:

A beat-‘em-up game would not be one if the player character is unstoppable. Therefore, the player character has a health meter, which shows how much punishment which he/she can take before he/she goes poof. Health can be recovered by defeating enemies when in combat or passing by checkpoint shrines when out of combat.

Even at their initial level, the player character’s health reserves are considerable enough for him/her to take a significant beating, at least at the default difficulty mode. There are enemies which do hit hard, but their patterns are easy to learn and they are often no match for the player character’s agility.

Furthermore, the health meter can be extended by collecting fragments of magical heart containers (which is an activity that is a nod to a certain Nintendo franchise). The extensions are small, but there are quite a number of heart containers to be found.

Getting hurt always causes the player character to be knocked prone; precious seconds are lost before the player character gets up. In some scenarios, such as one in which the player character is chased by a certain gigantic monster, this loss of time can be costly.

Fortunately, in other scenarios, it is not that disastrous. Furthermore, when the player character is damaged, his/her sprite blinks for several seconds; these “invincibility frames” (to use an old term which originated in the SNES era) grant the player an opportunity to get out of a bind.

With such convenient and very forgiving gameplay designs for health, it is a terrible player indeed who cannot overcome the combat-based challenges in Guacamelee!, at least those which occur outside of the optional challenges (more on these later).

STAMINA:

For all the magical strength which the player characters have, they are not inexhaustible dynamos of puerility. Although they can punch, kick and jump without tiring, special moves, namely those which they obtained by absorbing powers from statues, cannot be used willy-nilly.

The player characters have yellow squares under their bars which show how many moves which they can perform before they are over-stressed (an occurrence which is depicted by their sprites being tinted an alarming red).

The player character’s stamina can be increased by collecting pieces of magical skulls, which when completed grant one additional square each. Yet, there are only so many skulls to be collected, so the player cannot spam moves indefinitely.

OLMEC HEADBUTT:

There may be a balance issue with the Olmec Headbutt. Before explaining, it should be said first that almost any enemy, except humongous ones like giant skeletons, can be knocked around if they suffer enough damage in a short time. This includes bosses.

Usually, the game balances this by making sure that enemies have some means of preventing too much damage from being inflicted on them in a short time. In the case of bosses, they usually have some escape moves, such as Jaguar Javier’s dashing move.

The Olmec Headbutt move circumvents this. Olmec Headbutts appear to be able to inflict enough damage to immediately bounce enemies around the screen. If the player can get the player character to where enemies would land and time the use of another headbutt, any enemy, including most bosses, can be juggled around. Of course, there is limited stamina to be concerned about, but it can regenerate while the player is having the player character run over to where enemies would land.

THROWING:

A luchador would not be one if he/she cannot toss opponents around. In the case of the luchador in Guacamelee!, he/she can throw enemies very far. However, the player character cannot throw enemies willy-nilly; they have to be weakened a bit before a button prompt appears over their heads, showing that they are vulnerable to grappling.

There are many incentives to grapple and toss enemies around. The most lucrative of these is that the animation frames for throwing renders the player character invulnerable; this is an advantage which is incredibly valuable when there are hordes of enemies on-screen, such as those which occur in the El Infierno challenges (more on these later).

The second-highest incentive is that a thrown enemy is a projectile that can hit other enemies, immediately knocking them off their feet. In fact, it can be very entertaining to keep tossing enemies in order to juggle a gaggle of enemies.

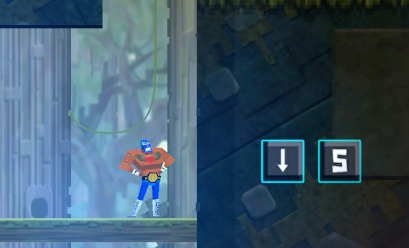

MOVE LIMITATIONS WHEN JUMPING:

There are restrictions which are placed on the moves which the player character can perform while he/she is in the air. The main restriction is that each special move can only be performed once; the game will keep track of the moves which have been used. Any attempt to reuse a move results in a jarring noise and the flashing of the player character’s sprite, as well as failure to enact the move.

The game does not exactly inform the player about this through a tutorial. Without having been informed through third-party sources, the player will have to discover this the hard way.

COINS & SHRINES:

Throughout the game, the player will be collecting coins, usually those released by defeated enemies. (There are some coins which are floating about, but these are so few and likely serve merely as homage to a certain Nintendo franchise.)

The amount of coins which can be obtained from enemies can be increased by introducing more variety into the chain of moves which are used to beat them up with, in addition to simply hitting them more.

Coins can then be spent at shrines. The most appealing purchases are those which improve the player character’s capabilities, such as the amount of health recovered from defeated enemies. However, the options for these are eventually exhausted, because there is far more money to be had than is needed to satisfy the purchasing costs.

Afterwards, the player can only spend money on costumes, which alter the player character’s capabilities. Some of the costumes are amusing, but they are otherwise palette swaps of the player character’s sprite (albeit with some functionality instead of just purely aesthetic changes).

Overall, the gameplay element of gathering coins and purchasing stuff with them is not that particularly exciting; unlike the other gameplay elements of Guacamelee!, it does not do anything refreshing.

CHICKEN MODE:

Perhaps in a stroke of humor, Drinkbox has implemented a feature which lets the player character turn into a masked chicken.

The main function of this mode is to let the player character access narrow tunnels. Being a chicken also means that the player character is a small target, which helps a bit when all the player wants to do is to bypass enemies. Otherwise, there are not that many practical reasons to use this mode.

DIMENSION-SWAPPING:

Early on in the game, the player is introduced to the Land of the Dead. It is a mirror of the realm of the living, but with some differences, the most obvious of which are the aesthetics.

However, the player does not get to go to the Land of the Dead until a few locations later in the playthrough. Even then, the game only allows the player to switch realms using portals.

Some things exist only in the realm of the living, whereas some others appear only in the Land of the Dead; these objects can be spotted where there are sparkles. Switching between realms is often needed in order to circumvent obstacles which are in the player’s way. Furthermore, some enemies exist only within one of the two realms and can only be damaged when the player character is in that realm.

Eventually, the game grants the player the ability to switch realms without using portals. This is also when the game starts introducing reflex-oriented obstacles too. The player will need to mash the realm-switching button in accordance with the frequency of the placement of obstacles which are placed in the player’s path.

This kind of challenge can be a bit hectic, but fortunately, there are just enough of them to be palette-cleansers instead of frustrating hindrances.

ENEMIES:

Most of the enemies in the game are either undead or demons.

Firstly, there are skeletal bandits, of which there are three variants. The green ones serve as fodder; this is something which the game will express in very obvious ways in the gauntlet levels (more on these later). The red ones are the first of enemies which have ranged attacks, and are only ever a threat if the player has to fight in precarious places or has to face multitudes of them at any one time. Then, there are the yellow ones, which are more formidable thanks to their considerable agility.

Later, these undead bandits are joined by giant undead armadillos who roll/bounce around, Chupacabra demons who fly and spit magical bolts which pass through obstacles, and even grenade-tossing cacti which can only be defeated by throwing stuff at them.

Much later, undead ancient South American warriors join the fray. These are much tougher than the previous enemies; there is a shaman of sorts with a wicked mechanical arm who happens to be able to conjure lightning, a four-armed swordsman who is a whirling dervish, a brute with a massive mallet and considerable reach and a giant.

Experienced players will eventually figure out the weaknesses of every enemy in the game. However, in some challenges, the enemies come in very troublesome combinations. For example, in some of the El Infierno challenges, the nimble yellow skeletal bandits spawn together with the flying Chupacabras, making for a tough fight as such a combination can juggle the player character incessantly, despite the aforementioned invincibility frames.

SHIELDS:

Sometime into the game, enemies with magical shielding are introduced. These have layers of shields, which are depicted as additional outlines offset at small but distinct distances from their sprite silhouettes. These shields render them immune to damage as long as they are operational.

Interestingly, shields do not make enemies unstoppable. They are still vulnerable to being hit and knocked around. This means that if the player can juggle them around, he/she can deal with them at his/her own leisure.

Nevertheless, to eliminate them permanently, their shields have to be brought down. To do this, the player has to perform moves with colours which match the colours of the shields, or in the case of multiple layers of shields, repeatedly hit with rapid combos. After the shields are down, the player has only close to ten seconds to inflict damage before the shields come back up; sometimes, they may even be of different colours.

If there is any problem to be had with this otherwise solid gameplay element, it is that it may not be kind towards the colour-blind.

(NOT) FALLING OFF LEVELS:

A certain infamous characteristic of platforming games is that there are level boundaries which when crossed, immediately kills the player character. Fortunately, Guacamelee does not have this irritating game design, despite having a lot of nods to old-school platforming games.

When the player character reaches a level boundary which would be a fatal abyss in other games, the player character teleports back to the last solid platform which he/she was on. This is very convenient, at least for levels where urgency is not an issue.

THORN VINES, SPIKE TRAPS, RESET SPIKES AND SAWS:

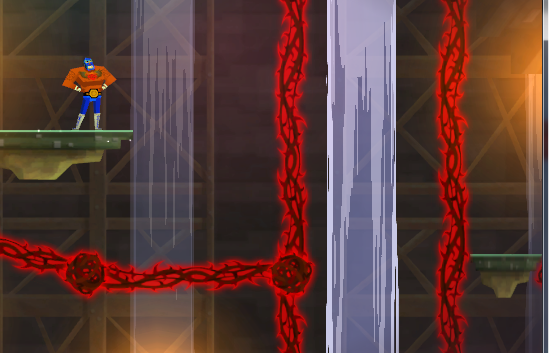

Obviously prickly environmental hazards tend to be a norm in platforming games; Guacamelee is not an exception. Interestingly though, there are at least four types of such hazards, one of which is more of a source of annoyance than harm (especially in the El Infierno challenges).

The first of these are the thorn vines, which are introduced in the forest stage but are later found elsewhere. These often stretch across the air; if the player character comes into contact with them, he/she is knocked back and has to waste time getting back up.

Therefore, the player character has to perform an air-dodge to bypass them. However, air-dodges will cause the player character to lose jumping momentum, which is something to keep in mind during the tougher platforming challenges.

Next, there are spikes which are set along the floor, walls or ceilings. These also knock the player character back (instead of simply poking him/her, for whatever reason) when he/she comes into contact with them. Interestingly, they kill any enemy which is thrown into them immediately; this is a lesson which the player will learn through observation, because the game will not inform the player about this.

However, spikes which are colored green will reset the player character to a previously stable location, not unlike level boundaries. These appear particularly often in the challenges of El Infierno, acting as hazards which cause the player to waste precious time.

Finally, there are saws. These automatically kill the player character if he/she runs into them. Curiously though, not all saws appear to damage enemies which are thrown into them. The saws do not seem thematically compatible with the rest of the game, but they may be an homage to Super Meat Boy.

OPTIONAL CHALLENGES:

There are a couple of stages which are optional to the experience of a playthrough; these stages do not have to be attempted in order to reach the conclusion of the story, though they have some rewards which lead to the alternate ending of the game. Incidentally, these stages are a lot more difficult than the others in the game.

These stages are the mines near the town of Santa Luchita and El Infierno itself (which has to be reached by paying a fee to a certain individual in the deserts near Santa Luchita). They will be described in their own sections.

In addition, there are hidden places throughout the other stages which contain doors to the otherworldly realm of Chac Mool. The significance of these places to the story is not entirely clear, but they do contain magical orbs which will be needed in order to unlock the happier of the two endings for the game. More often than not, the player will need to perform some difficult platforming to reach the orbs.

GAUNTLET LEVELS:

The mines which are near Santa Luchita have somehow been infested with undead and demons. Certain sections of the mines trap the player character, forcing him/her to fight off waves of these enemies. The fights occur in a long stretch of rooms, each one more dangerous than the last. If the player character perishes, the player has to restart the entire stretch. It can be grueling and frustrating, but such is the price of the optional challenges.

Incidentally, these fights involve enemies which only appear late in the game. It can be a jarring experience to encounter them for the first time while trying to survive the gauntlet challenges.

EL INFIERNO CHALLENGES:

Unlike the challenges in the mines, those in El Infierno are a lot more sophisticated – and also a lot more frustrating because they are so vastly different from the other challenges in the game.

These challenges include special variants of enemies which are barely seen in the other stages, such as enemies with almost-complete invincibility and enemies with attacks which immediately kill the player character if they connect. There are also a lot more hazards, especially spikes and thorn vines.

Surviving is often not the only goal in these challenges. To obtain better accolades (and thus unlock the rewards in El Infierno), the player must achieve other goals, the most common of which are achieving a minimum combo score, or completing the challenge under specific lengths of time. For some challenges, the goal is to simply complete them, but these challenges tend to be even more difficult than the rest.

Generally, the player will need to a practice a lot in order to achieve the secondary goals in the way the game’s developers intended. However, a clever – and unscrupulous – player would eventually learn of rather exploitative solutions to achieve the goals. For example, most of the combo goals can be achieved by using the chicken form’s very weak attacks against pathetic enemies, such as the green skeletal bandits. It is effective, but cheesy.

Furthermore, the challenges in El Infierno are perhaps the only parts of the game where the alternate costumes are useful, and even so, only some of them are. For example, the Skeleton costume (which happens to make an appearance in the regular credits roll of the game) is likely to be the one which will help the player overcome the 16th challenge in El Infierno.

Whether by hook or by crook, the challenges in El Infierno can seem like a lot of work for very little reward - more so when the player realizes that the rewards are mainly costumes. Perhaps there is some amusement to be had from learning how Guacamelee’s take on Hell is like, but such humour is nothing new in the history of storytelling.

SIDE QUESTS:

Puebloblucho and Santa Luchita are populated by people – people who had been quite inconvenienced by the events involving undead which occur during the course of the game. As such, they need the aid of a hero, namely the protagonist.

Their requests will not be worded in a log or such other record-keeping features, however. The player will need to keep these in mind himself/herself.

Fortunately, it is more than likely that the player will go about fulfilling these as he/she explores the various stages or backtracks to places where the player character previously could not access but later could, thanks to recently received powers.

Most of these side activities grant pieces of heart containers or magical skulls, so there are strong incentives to pursue them. Furthermore, they are the main source of one aspect of the game’s humour.

One of these side activities may have more practical benefits than the rest. This is Combo Chicken’s gym, where the player character has to line up a sequence of moves, each of which is more complicated than the last. Although these moves would be difficult to execute when there are a lot of enemies in the game, they happen to be quite devastating against tough individual enemies, such as the mallet-wielding brute and storm-conjuring shaman which appear later in the game.

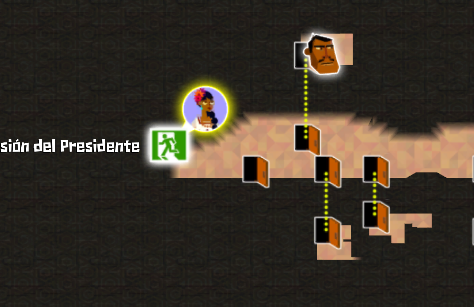

MAP SYSTEM:

The map system in Guacamelee is, at best, barebones. It shows the boundaries of the places which the player has gone to. It also has colour-coded labels for obstacles which have to be destroyed with special moves and realm-switched obstacles, though the player has to figure out the colour-codes on his/her own.

It also has door icons to show which region of the stage is connected to which other region. A mostly-reliable fog-of-war feature shows where the player has gone to and which other parts of a stage which the player has not.

In other words, the map system is just decent enough to help the player figure out where to go next.

However, it has several noticeable shortfalls. The first and foremost of these is that it does not indicate the presence of wooden platforms, hazards, stairs and enemies. The absence of any representation for wooden platforms can be particularly bothersome, especially for the platforming segments which lead to Chac Mool portals.

EASTER EGGS & REFERENCES:

Not too long into the playthrough, the game introduces the first example of its humour. The player character can smash liquor barrels apart quite easily, which is a feat that a certain character will point out as being quite difficult in real life. (This is, of course, an indirect remark about logic in video games.)

Then, the game introduces a reference to certain Nintendo games through actual happenings in the gameplay, such as a certain boss being defeated by having a bridge disintegrating underneath it after the player character has reached the other end of the bridge.

The settlement of Santa Luchita has doles of such references, in particular, almost to the point of being tiresome (in the eyes of players who had more than their fair share of popular culture references, that is).

In addition to these kinds of references, there are also references to some of Drinkbox’s earlier games, such as Mutant Blobs Attack!!!, and other indie games such as Castle Crashers. There are also citations of Internet memes. These references are given a veneer of Mexican/Spanish word-play, e.g. “Casa Crashers”, if only to fit them into Guacamelee’s setting.

MORE POIGNANT MOMENTS:

Interestingly, Guacamelee is not all laughs. An example of this can be seen in a small errand where the player character retrieves a luchador doll for the spirit of a deceased child in a now-quiet household.

The biggest contrast to the game’s pervasive silly humour is the default ending and credits reel. To describe it would be quite the spoiler, but it should suffice to say that to an astute observer, its tone is different from that for the seemingly visually similar “happy” ending (which has to be unlocked by collecting all magical orbs from Chac Mool).

HARD MODE:

After completing the first playthrough, the player gets the opportunity to replay the game in “Hard Mode”. Typically, “Hard Mode” increases the amounts of damage which enemies can take and decreases those for the player character.

Fortunately, there are a few more substantial differences. Some enemy encounters are noticeably different. For example, the boss fight against a certain witch will have two smaller platforms instead of just one. As another example, a certain jaguar warrior would happen to have faster animations.

Yet, there does not appear to be any additional and substantial reward for attempting and completing Hard Mode, other than the usual meta-game trophies and achievements.

VISUAL DESIGNS – OVERVIEW:

Guacamelee makes use of 2-D models with separately animated segments; this would be noticeable to veterans of indie games who had seen such visual designs since 2008’s Aquaria or even earlier. The segmentation can seem more acute than other games which use similar animation methods though. This is exacerbated by the considerable amount of sharp edges on the models of characters.

Yet, Guacamelee’s visual designs are still charming enough and would not look too primitive, at least in the eyes of anyone who is not already averse to a “cartoony” look. The animations of the 2-D models, in particular, are fluid enough to have someone overlook the cruder details of the models.

For better or worse, Guacamelee’s visual designs have certain qualities which are notable, as will be described shortly.

PALETTE SWAPPING:

Unfortunately, Guacamelee is one of those game which resort to palette-swapping, that is, the reuse of sprites with the same silhouettes, albeit with different shades, hues or slightly different textures.

This is most noticeable with the undead armadillos, of which there are two types but both of which have the same shape. The same can also be said about the demonic plants, both types of which display flowers of the same shape when they travel through the ground. Players who have trouble differentiating colours would likely only know which is which when they start attacking. (The main differences are in their attack patterns, by the way.)

Fortunately, in other cases of palette-swapping, such as the skeletal bandits, the sprites have very different animation sets. For example, the yellow bandit scurries around on all its limbs, whereas the other two types do not.

FLASHY COLOURS:

Guacamelee draws from Mexican culture, which is already literally colourful, and Drinkbox’s artists have a penchant for using a wide range of colours in the visual designs of its games. Therefore, Guacamelee has a garish range of colours, and eagerly flaunts it with lots of flickering.

However, all that garishness and flickering pose health risks to people who have epilepsy or similar conditions. Drinkbox happens to be aware of this, but all it has seemingly done is include a warning which appears when the game is launched. There is no option to disable the flickering of colours which occurs during the game, specifically when the player completes a heart container or magic skull, or when the player character gains a new power.

SOUND DESIGNS:

Not unlike Drinkbox’s earlier games, Guacamelee lacks any legible voice-acting. There are grunts and groans for the player characters and growls and snarls for enemies, but this is all there is to the voice-acting.

The sound effects for combat are a lot more satisfying. The punches and kicks sound suitably meaty, and the thumps of enemies being smashed are a source of gratification. There are other entertaining sound effects, such as children cheering when money pinatas pop up.

The best sound designs in the game belong to its soundtracks, which are composed in-house. Typically, there are sounds which resemble those made by Mexican musical instruments, e.g. the guitarrón and vihuela, and older instruments based on those used by ancient American natives. Of course, only experts of Mexican music would be able to determine whether these are naturally authentic or are electronic facsimiles.

Either way, the music in Guacamelee is fittingly upbeat, thus matching the game’s focus on fast-paced combat and platforming. There can seem to be a bit of recycling though, because each track which is used for the land of the living has a slightly more ominous counterpart which is used for the Land of the Dead. (Switching between the two is a smooth experience, however.)

KEYBOARD USE:

The computer version of Guacamelee does support the use of the keyboard, though there has been no effort to utilize the mouse, other than using it for the menus. For the purpose of punching, jumping and using special moves, the keyboard is just barely adequate.

Unfortunately, the directional inputs are almost useless for the purpose of throwing enemies around, because they can only be reliably used to aim throws in the eight cardinal directions. There might be some way to aim throws in between the cardinal directions, but if there are, the game does not appear to have any tutorials or documentation for this.

To this day, Guacamelee remains a game which is best played with a controller, perhaps to the chagrin of anyone who doggedly refuses to use anything other than the keyboard and mouse for games on the computer platforms.

CONCLUSION:

Coming from an indie game-maker which had made games that are not excellently remarkable (e.g. the two Tales from Space game), Guacamelee is a splendid surprise.

Its blend of platforming is, of course, not brand-new (it has been done in games like Metroid). However, considering the gaming space for indie platformers at the time – which was being saturated with increasingly cookie-cutter titles - Guacamelee was a breath of fresh air. There is its purportedly short length, but it is difficult to imagine how it could be made longer without it resorting to a lot of padding.

Coupled with effective fighting mechanisms which reward both talent and practice, Guacamelee is hard to fault.