INTRO:

The crossing of genres in the video game scene has been around since the early 1990s. The results – called “hybrids” by some – have appeals that games with “purer” gameplay do not have. One of the appeals is the curiosity of whether such a mix of gameplay can work out or not.

Crypt of the NecroDancer, developed by Brace Yourself Games, is one such endeavour. Specifically, it combines rhythm-matching gameplay with the basics of a rogue-lite. The result is a game which rewards the player with further challenges and more content as he/she perseveres and becomes better.

PREMISE:

Crypt of the NecroDancer is set in a fantastical world where music appears to be a significant aspect of existence. The plot is oriented around a series of ladies, the first of which is Cadence, the daughter of a treasure hunter and an absentee father. Cadence takes little guff from anyone, including her elders, but pays the price for her defiance after falling into the trap of the titular NecroDancer.

She becomes trapped in the underworld realm where music holds sway and everyone dances to some beat that they hear all the time. Cadence has to delve through this realm, defeating enemies and eventually gaining enough power to challenge the NecroDancer and learn more about her forebears (who are the other ladies).

The plot is really only there to give some backstory to the gameplay. In truth, there is actually a serviceably tragic story to be had from the ladies’ travails. Yet, it is unlikely to hold the player’s interest past the moment when the player sees the lobby floor for the first time. (Not to mention that much of the plot is about the ladies’ misunderstanding of many things that they thought they knew about.)

MUSIC:

Usually, in the reviews that I would write, the music is relegated to the later sections. In this game though, the music is apparently a considerable part of the presentation and supposedly the gameplay, so it will be described before the rest of the game.

The music has been composed by Danny Baranowsky such that their original tempo matches the default beat rate which governs the rhythmic movement that is the core of the gameplay (and which will be described further later). When the beat rate changes, the tempo of the music also changes. The length of time that the player would be able to play a level is also dependent on the length of the track which is used for the level.

Even outside of the game, the music is worthwhile listening to; the tracks are some of the best and most upbeat that Baranowsky has ever composed. Of course, in this matter, Baranowsky deserves the credit instead of the developer.

RHYTHMIC MOVEMENT:

The dungeons happen to have been enchanted with an infectious musical beat. The beat has everyone in the dungeons, which include the player character and the monsters, moving in tune with its tempo; NPCs and monsters, in particular, exhibit this through their animation frames.

The player character is perhaps the only exception to this, being nominally under the control of the player. However, the player has to make movement inputs in time with the musical beat anyway: any out-of-sync movements are roundly ignored by the game. In the case of some player characters, this can have severe consequences too.

This gameplay mechanism is the core appeal of the game. Players are rewarded for keeping up with the tempo, typically through exponentially growing score multipliers (which also provide some practical benefits). In the case of the more challenging player characters (such as Cadence’s forebearers), keeping up with the tempo is essential. It is a measure of a player’s skill (or rather, familiarity) to be able to complete runs through the dungeons with splendidly high multipliers.

As mentioned already, enemies also move according to the beat. However, their frequency of movement is lower than that of the player character; most monsters move half as slowly as the player character can. Of course, how successful the player is at taking advantage of this disparity is dependent on his/her skill.

It has to be said here that players who had stayed away from rhythm games because they have no patience for rhythmic inputs (such as myself) might want to reconsider their decision to play this game. Of course, there are many gameplay elements other than rhythmic inputs in Crypt of the Necrodancer, if the player is more interested in these.

CONTEXT-SENSITIVE ACTIONS:

Interestingly, the only control inputs which the player has are the movement direction inputs. If there is nothing in the immediate vicinity of the player character, he/she would make a move in any of the four cardinal directions.

However, if there is something in the vicinity, entering a movement input in its direction will have the player character doing something that is generally appropriate towards whatever that thing is.

If the other thing is an enemy, the player character attacks it if it is within range. In fact, making an attack against an enemy is the highest priority action, if there is more than one kind of action that the player character can do. This is usually acceptable most of the time, unless all the player wants to do is break open a chest, take its contents and run.

Speaking of which, if the other thing is a chest or a door, the player character will open them. This may not always be desirable, but there is a handy limitation which prevents any accidental door or chest opening: the door or chest must be adjacent to the player character in any of the four cardinal directions.

CHARACTER AND MONSTER NAMING:

If the title of the game is not an obvious enough hint already, the writers for the game have gone out of their way to name every character (and some monsters) after terms which are associated with the field of music. The names are either musical terms taken wholesale (such is the case with Cadence and most of her relatives) or subjected to wordplay (such as the NecroDancer).

Most of the names are amusing, especially those that are actual musical terms. However, the ones with wordplay can give the impression that the writers are trying a bit too hard to have everything match the musical theme of the game. (The “NecroDancer” is the most obvious example of this whimsy.)

OCTAVIAN & NO TEMPO:

There is a player character by the name of Octavian (known in-game as simply “The Bard”). He is a bard who moves according to his own tempo. In gameplay terms, the beat meter is absent. Any missed inputs will not harm the player at all and there are no clocks which would limit the player character’s time in the current level. In fact, other characters can only make their moves after Octavian’s.

In other words, Octavian is meant for players who prefer more control over the pace of their progress. On the other hand, not having to keep the tempo in mind also removes the main appeal of the game. At best, Octavian is useful for the purpose of learning about the hazards and denizens of zones that the player has yet to be familiar with.

LOBBY:

There are few menus to navigate through in Crypt of the NecroDancer. Instead, most of the options for gameplay are accessed through the Lobby level.

The Lobby level is a floor with what is best described as a foyer. The foyer has several staircases which represent gameplay options. To access these options, the player character has to move onto them.

Accessing gameplay options with actual gameplay controls is nothing new in video games; it has been around since the first Quake. It may well be more efficient (though perhaps more boring) to use menus for this purpose.

Yet, it does serve one purpose in Crypt of the Necrodancer: it helps the player maintain his/her pace with the tempo, which is present in the Lobby level. (On the other hand, the player is not penalized in significant ways for missing beats while in the Lobby, so this benefit is quite minor.)

ADJOINING ROOMS IN LOBBY & SERVICE PROVIDERS:

The rooms that are adjacent to the foyer would be of more interest to the player in the long run. These rooms are occupied by NPCs, which offer services that also double as the ‘rogue-lite’ elements of the game.

Not all of the rooms are initially available for perusal. This is because most of their associated NPCs have yet to be rescued from the dungeons. There is at least one NPC for each zone of dungeons, and he/she happens to be in one of the non-boss levels. He/She is locked up in a cage, which has to be opened with a special key that is tucked away somewhere in the same level.

The special key may be a gold key, in which case it would stay in the player’s possession until it is used to open a cage. The other kind of special key is a glass key, which breaks and is lost immediately after the player has taken a hit. Therefore, the player would have to be more careful when getting this key to the cage. (Incidentally, the glass key is needed to rescue an NPC which is perhaps the most useful service-provider in the long run.)

HEARTS:

Like so many other games with deliberately retro visuals, Crypt of the Necrodancer harks back to the days when the durability of the player character is represented with hearts. In its case, the hearts are large unmistakeable icons. Most hits that the player character suffer would take away half a heart each, but there are enemies which hit harder and thus take away more. Obviously, if all of the hearts are gone, the player character is dead and the run is over.

It is generally in the player’s interest to avoid taking damage whenever possible. The player character’s health can be restored in several ways, but they are not very common.

One of the methods of healing is of course the time-honoured tradition of eating video game food and somehow being healed from doing so. Some player characters start with some food, e.g. Cadence starts with an apple. There are higher-grade foods, such as hunks of dubiously preserved meat which can restore a lot of hearts.

GOLD:

Dungeons would not be dungeons if there is no loot to be swiped. In the case of those in Crypt of the Necrodancer, the loot is in the form of many gold coins and the occasional pieces of gear. Gold – and gear – which has been collected in a run cannot be used in other runs, even if the player managed to be successful in the current run. (Gold and gear are certainly lost if the player character is killed.) Therefore, it is in the player’s interest to dispose of gold through purchases whenever possible, unless the player is aiming for high scores based on gold that has been collected.

DIAMONDS:

The dungeons have a rarer kind of treasure: diamonds. They are much more difficult to find than gold.

Sometimes, a few diamonds would be floating about in plain sight, waiting to be picked up. Some are in chests, while others are in walls, with no indicators as to which ones have them and which ones do not.

This rarity is perhaps warranted: diamonds are the only currency items which can be brought back to the lobby. However, the player is not allowed to accumulate them anyway. Before every run, all diamonds must be spent; any unspent diamonds are lost upon the start of the next run.

LIMITED LEVEL TIME:

Considering what has been described about Diamonds, one would think that with enough time, the player could uncover all the diamonds and other treasures in a level.

However, this is not possible, because there is a time limit, or rather a limit of beats to every level. After this time limit is reached (which is visually indicated by the reddening of the beat indicators at the bottom of the screen), a trapdoor somehow appears under the player character and sends him/her to the next level (to the accompaniment of his/her humorous scream).

CHESTS:

As to be expected from dungeons, the dungeons in this game have plenty of treasure chests lying around, waiting for player characters to literally break them open and loot them.

The color of the chests usually indicates what they have. For example, the brown ones usually have consumables or trinkets in them, whereas the black ones have gear pieces.

Interestingly, the player could pay the Dungeon Master NPC in order to increase the number of chests in the dungeons of the next run. The costs increase after each payment, but this is a worthwhile investment.

RANDOMIZED SPAWNING OF SPECIFIC GEAR PIECES:

Generally, the player’s skill and familiarity with the game is the main factor of success in a run. However, having useful gear which increase the player character’s capabilities will greatly improve the player’s chances.

The keyword here is “useful”. The gear pieces which the player may obtain might be mundane but reliable, such as a bigger sword which does more damage but little else.

Other gear pieces may be more interesting. They have as many drawbacks as they have advantages, such as powerful but fragile “glass” weapons which break as soon as the player character takes damage. There is also gear that is versatile but not does not do enough damage to be competitive as the going gets tough, such as whips which have considerable range but cannot quickly knock out dead-hard enemies like dragons.

In order to capitalize on the use of the more esoteric gear pieces, the player character needs to be already in a condition that is conducive to their use, and is also in a scenario where they would be useful. For example, “Blood” weapons would be quite useful in a boss fight if the boss is accompanied by plenty of weak minions; the weak minions would be fodder for the weapons’ ability, which grant health to the player character after a certain number of kills have been achieved.

To put it simply, although the player’s skill and familiarity are still the main factors, luck still plays a part in the gameplay, for better or worse.

SWAPPING GEAR:

In the hands of a skilled player, gear which is appropriate for the player character’s current situation can make the dungeon runs a breeze. If not, the gear pieces are little more than hindrances. Fortunately, the player could swap back to the previous piece of gear, which is left where the current gear pieces were found. However, there is no option to discard unwanted pieces of gear and fall back to default gear.

THROWING SPEARS AND DAGGERS:

The weapons which the player character can wield (assuming that the player character can use any weapons at all) include spears and daggers. In addition to whatever abilities that they have, spears and daggers can be thrown with a tap of a button. They will fly down a row of tiles, depending on the player character’s facing. Obviously, they stop when they hit something. However, the player character is left without a weapon until he/she can retrieve the spear or dagger where they landed (assuming that they are not Glass weaponry, which break upon impact with walls).

The other types of weapons cannot be thrown, but they do have some other advantages to compensate for their lack of ability to be improvised projectiles. For example, where spears can only jab towards the cardinal directions, swords can make attacks in diagonal directions.

TORCHES:

Interestingly, the gear piece that is the Torch has its own equipment slot. Observation (or reading the wiki entry for it) would reveal that the Torch serves a couple of gameplay functions which other gear pieces do not.

The first function is illumination of the player character’s immediate surroundings and the removal of the fog-of-war which initially covers a level. Walls appear to reduce the illumination range of any torch, but do not completely block it; a particularly bright torch can still illuminate spaces behind walls. Of course, this makes the search for hidden rooms much easier.

On the other hand, there is the second function of the torch; it alerts monsters to the player character’s presence, thus drawing them over to the player character if they are of an inclination to make pursuit. This may or may not be a good thing, depending on the player’s preferred playstyle.

CONSUMABLES – OVERVIEW:

Consumables are, as their name suggests, only usable once. They are several different types of consumables however. Therefore, unless the player has found upgrades which allow the equipping of multiple consumables, the player would have to make some decisions on which consumable to take. The types of consumables will be described shortly.

FOOD:

When in doubt of which consumable to take, food is the go-to option. This is because there are few sources of healing in the game, and food is the most reliable of them, as well as (obviously) the most portable.

SPELLS:

Few of the player characters are wizards, so typically the spells which they can use have to be invoked using scrolls. In fact, the player characters invoke them with plenty of fanfare, uttering the names of the spells out loud.

There are many types of spells, most of them being quite useful in many situations. Indeed, if there is any reason for the player to withhold their spells, it is to figure out when it is optimal to use them.

For example, there is the Earthquake spell, which as its name suggests, causes walls to crumble as well as hurting all nearby monsters for 1 point of damage. Therefore, the player would have to consider using the spell when fighting against hordes of weak enemies, such as King Conga’s zombies, or to use the spell to shatter walls, such as a convenient location where there are a lot of golden walls in the vicinity.

BOMBS:

As to be expected of a game with dungeons and a presentation which more than resembles Legend of Zelda, there are cartoonish spherical bombs with cord fuses in this game.

Bombs can be used to blow up enemies, if the player can time them correctly. Alternatively, and this is perhaps their likelier use among players, bombs can be used to blow up walls and other things.

DRUMS:

Drums occupy the slots for consumables, but they are not consumed upon use. Rather, the player can use them multiple times – if the player can live with the consequences of using them.

There is the War Drum, its use of which requires the player character to stand still. Although this also means that the player would not miss a beat by not moving, there is the matter of the player character standing still, which is not always desirable, especially against enemies with powerful but delayed attacks.

Next, there is the Blood Drum. Using it immediately hurts the player character for one-half of a heart, but for the next beat, the player character does tremendous damage and can shatter walls. Obviously, this would be very useful in the hands of an experienced player.

HEART TRANSPLANT:

The Heart Transplant is an obvious reference to the intro cutscene of the game. Anyway, it is an item which allows the player to ignore the beat system. On the other hand, this is practically like playing Octavian for a while.

It would have been remarkable if the frequency of the player character’s actions becomes equal to the player’s rate of input during the duration of this power-up, i.e. the player character can spam moves and attacks while enemies still move at their own regular pace.

HOLY WATER:

Despite what its name suggests, the Holy Water is essentially a ‘vampiric’ video-game weapon, i.e. it damages enemies and heals the player character for an amount that is proportional to the damage inflicted.

SCROLL OF NEED:

The Scroll of Need is perhaps the most welcome of the consumables. Its effects vary according to conditions which are not documented, but are observable over time (or with data-mining).

For example, if the player character somehow has yet to replace his/her default weapon (which is usually a dagger), using the Scroll of Need will grant a weapon of a higher grade. As another example, if the player character is running low on health and does not have any healing item, the Scroll creates a healing potion.

This is nothing new in video games, of course; this has been seen as early as Neverwinter Nights. However, such conditional coding for usable items are rare in video games, and Crypt of the Necrodancer should be commended for doing something that is rare.

SHOVELS & DIGGING:

The protagonist is a miner, and the NecroDancer’s crypt is not entirely made of stone or metal. Therefore, it is convenient that the player character is equipped with a shovel by default. The shovel also occupies its own equipment slot.

Anyway, the shovel is primarily used for digging; it cannot be used as a weapon. The player character can dig with tireless gusto, but his/her ability to dig is held back by the limitations of the shovel, specifically the strength of its materials.

The default shovel can dig little more than dirt walls. For stronger walls, shovels of harder materials are needed. Trying to dig a wall that is harder than the player’s current shovel results in failure and the loss of any beat multiplier.

Other than digging, the shovels do little of anything else. (This is rectified in the DLC, however.)

As for the act of digging, it is as simple as attacking; the player character needs to be adjacent to a wall that the player wants to dig, and then the player makes a movement input in the direction of the wall. If the shovel can break the wall, the wall crumbles and an empty space is yielded. If the wall is containing anything, it is released for the player character to deal with.

HEADWEAR & FOOTWEAR:

Unlike the other pieces of gear in other categories, the pieces of gear in these categories are a lot more varied. In fact, each of them is quite different from the others.

For example, there is the headwear item, the Miner’s Cap; as its name suggests, it helps digging. There is another headwear item, the Crown of Greed, which has nothing to do with digging, but instead doubles the gold that is retrieved by the player character (but somehow steals 1 gold-piece every beat).

On the other hand, many footwear and headwear items come with caveats that are either subtle or overt. For example, in the case of the Miner’s Cap, the walls to the left and right of the player character would also be collapsed when he/she digs a wall in front. This might be a problem if the player wants a narrow tunnel instead, in order to avoid breaching rooms full of enemies.

Fortunately, there are headwear and footwear items with mundane but otherwise reliable benefits. For example, there is the Helmet, which provides a slight increase to the player character’s armor rating.

RINGS:

A game with a fantastical setting like Crypt of the NecroDancer would not be complete without magical rings. Like footwear and headwear, each ring has properties which are unique to itself.

Rings have their own slot, though this slot can only accommodate one ring at any time. Most other games with fantastical RPG elements have at least two slots for rings, with the justification that the player character has two separate hands and thus should be able to wear two enchanted rings. That Crypt of the Necrodancer does not follow this trend is a complaint, albeit a minor one.

POWER-UPS:

Some treasures which the player character would retrieve do not act as gear pieces, but as power-ups which improve the player character’s survivability and performance. Understandably, these power-ups are rare.

Among these, there are bags, which allow the player to carry more consumables. Of the two bags, there is the Bag of Holding, which allows the player character to carry as many consumables as he/she can carry. However, this advantage is offset by a limitation in the user interface: the consumables have to be used in an order at which the most recently picked-up consumable has to be used before the earlier ones.

BOUNCE PADS:

Throughout almost all dungeons, there are pads with arrows which are set on the floor. When anything or anyone steps onto a pad, he/she/it is immediately propelled a tile in the direction of the arrow.

The player can step on a pad in order to get a boost in a direction which he/she wants to go to, or get more distance away from pursuing enemies. However, the best use of these pads is as buffers against enemies, who appear to be completely oblivious of the presence of the pads. For example, a skeleton that repeatedly hopped forth only to be bounced back can be a silly sight.

TRAPDOORS:

Trapdoors cause anyone or anything which gets onto them to fall to the next level. This is not immediately obvious, because something which drops to the next level can seem like it has been spawned for that level. Nonetheless, trapdoors do happen to do this.

Perhaps the most interesting use of trapdoors is that push-able objects can be pushed onto them, which causes them to drop into the level below. In the case of objects like the tough barrels, they are destroyed and will reveal their contents in the next level.

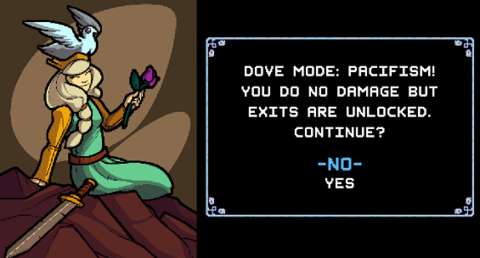

Interestingly, trapdoors do not appear when the player is playing as the Dove. This is perhaps to encourage the player to seek the exit staircase, which is, after all, always unlocked for the Dove at any level.

TEMPO PADS:

There are pads, which when stepped on by the player character (and only the player character alone), increase or decrease the tempo of the beat. This may or may not be desirable, depending on how quick the player can adapt to changes in the beat rate. The effect is temporary if the pad is stepped on, but it can actually become permanent for the entire level if the pad is somehow destroyed; learning this the hard way can be unpleasant (though perhaps amusing too).

SPIKE TRAPS:

Spike traps in Crypt of the Necrodancer are easy to spot. This is perhaps a presentation that contradicts a certain tradition about fantastical dungeons.

Anyway, the spike traps, as their name suggests, shoot out spikes a moment after they are stepped on. This works on enemies as much as they do the player character too, so the player could ostensibly lure enemies onto them, at least until the spike traps are destroyed. The spike traps can also be used to destroy crates and barrels, if the player can push them over onto the traps.

CONFUSE & TELEPORT TRAPS:

These traps are meant to disorient anyone who steps on them; this includes enemies in addition to the player character.

In the case of the teleport traps, they do have a chance of actually placing the player character in hidden rooms, though they are just as likely to dump the player character into a room full of enemies.

BOMB TRAPS:

Among the traps, the bomb trap is the easiest to evade and utilize against enemies. Stepping onto one spawns a bomb, which the player can use to destroy pursuers like he/she can with bombs that are actually planted.

ENEMIES – OVERVIEW:

Many enemies can be grouped into archetypes according to their behaviours. Obviously, observation is key to defeating them; experienced players would eventually learn of what to do whenever these enemies appear on-screen (when they do appear on-screen of course; there are some which are initially invisible). The following passages are more elaboration on the designs of enemies.

ZONE-SPECIFIC MONSTERS:

There are four zones in the vanilla package of the game. The first zone has the most straightforward enemies, whereas the subsequent zones generally have more troublesome enemies. For example, many enemies in the last zone are able to move diagonally as well as in the cardinal directions, something that most enemies in the first zone cannot do.

Again, the player will have to be observant in order to learn how to defeat them. In fact, they could ostensibly be beaten with a fresh player character with no upgrades. Indeed, the player would have to learn how to do this, because playing any of the zones from the lobby has the player starting the zone with a fresh character (unless the player has tricked him/her out with items purchased from the Diamond-Dealer, of course).

(By the way, there is a mode that allows the player to play all zones in a sequence. It allows the player character to retain upgrades from one zone to the next.)

DUMB ONES:

There are enemies who follow their own scripted behaviour, which does not include pursuit of the player character or any overt acknowledgement of the latter’s presence. Examples include most zombies, who follow their own scripted patrol patterns, and some slimes, which just hop on the spot. At worst, these enemies are hazards that get in the way when the player wants to deal with more threatening opponents.

PURSUERS:

Most enemies fall into this category. In the first few zones, pursuers are relatively slow compared to the player character, mainly because they can only move every other beat or every three or more beats, in the case of very slow enemies like the golems. However, their movement frequency is not the same as their attack frequency; learning this the hard way can be unpleasant.

EVIL GHOSTS:

There are ghost-like enemies named “Wraiths”, “Ghasts” and such other ‘undead spirit’ labels. As to be expected of ghostly enemies, they float over and through any obstacle in their pursuit of the player character.

Eliminating them before the other enemies is usually a good idea; this is made a bit easier because they often make shrill noises when they reveal their presence and begin their pursuit. However, ghosts that appear in the later zones have abilities which make them more difficult to eliminate, such as creating copies of themselves to distract the player with.

NOTICEABLE LACK OF TURRET-TYPE ENEMIES (IN VANILLA GAME):

In the original package of the Crypt of the Necrodancer, there are no enemies which act like turrets, i.e. they stay in place and shoot things at the player character. There are stationary enemies, but these behave more like hazards than something that is actively seeking the death of the player character.

(This gap would be later filled in the Amplified DLC.)

ENEMY-REPELLENT ITEMS:

Some treasures which the player character may find (or start with by default) happen to make certain enemies much easier to handle. For example, the Nazar Charm makes ghost-type enemies like the Wraiths a non-issue, whereas the Lucky Charm and Ring of Luck somehow reduce the aggression of bat-type enemies.

The player would have to learn about this through observation though, unless the player does his/her research through third-party documentation of course.

ENEMIES WHICH ARE REMOVED IN RUNS WITH SPECIFIC CHARACTERS:

Interestingly, certain enemies are completely removed from the dungeons if the player is playing specific characters. Sometimes, this is due to their starting gear; for example, Eli starts with the Nazar Charm, so ghost-type enemies are a non-issue.

However, in other cases, the reasons for the absence of certain enemies are likely gameplay-related. For example, some types of bats do not appear when the player is playing as Bolt, Aria or Coda. In the case of these characters, the omission of enemies is likely due to them being particularly troublesome for these characters.

GOLEMS:

There are some enemies which are obviously huge, and as befitting their stature, they take a lot more damage than smaller enemies to kill.

Some of these hulks are golems, which are very slow but hard-hitting brutes that can bash down walls in order to pursue the player character. They also happen to open paths through walls for other enemies too; this is the main threat which they pose.

Golems happen to be the prototypes for enemies which are designated as mini-bosses, which will be described later.

TRAIL-LEAVERS:

Some pursuit-giving enemies leave behind hazards as they chase after the player character. Examples include most elemental entities, which change the floor tiles to reflect their nature (and often into forms which are inimical to the player character). Obviously, these enemies should be dealt with quickly before they mess up the level for the player.

MINI-BOSSES:

There are some enemies which happen to be a tad more troublesome than the rest. Incidentally, they announce their presence and intent with loud noises like roars and growls.

The earliest-encountered among these enemies are minotaurs. In addition to pursuing the player character, they charge whenever the player character is in a direct cardinal line with them. Obviously, this is a cue for the player to do the ages-old cartoon-trick of stepping to the side and letting them collide with something hard.

Dragons are the other kind of mini-bosses that are encountered early, and perhaps more often than the player would like. Still, they are easy to deal with, assuming that the player character has enough space to dodge their breath-blasts and there are no other enemies that would get in the player’s way.

Banshees are powered-up versions of ghosts whose screams disable the music playback, among other audio cues. Obviously, in a rhythm-based game, this would be quite bad for the player unless he/she is already so familiar with the game that he/she has an ingrained sense of the rhythm.

As the player character moves through a dungeon, unexplored areas are lit and would stay lit. Nightmares, however, can re-darken already explored spaces, as well as hide the presence of any other enemies which are in their wake.

Most of the physically mighty mini-bosses can dig through walls to pursue the player character. Therefore, it is generally in the player’s interest to deal with them as early as possible to avoid having them open too many paths for other enemies to use for their own pursuits.

Perhaps the least impressive of the mini-bosses are the Dire-bats. The most that they would do is move about in random directions, though this means that they behave more like hazards than actual enemies.

MIMICS:

No self-respecting game with fantastical dungeons would be complete without monsters who pretend to be innocuous (or desirable) things. Crypt of the Necrodancer happens to have quite a variety of them, though Mimics are generally rare compared to other enemies.

Anyway, Mimics stay quiescent until the player character approaches, upon which they wake up and pursue the player character. There are a few ways to spot them, however. For example, Mimics which are pretending to be walls occasionally fidget in place, thus causing the “walls” to appear out of place and misaligned with other walls.

BOSSES:

Bosses are enemies which are often fought in relatively small levels. These levels are practically large rooms with neither walls that can be dug nor treasures that can be looted (at least before the bosses are defeated).

There are several different bosses, each with their own names and minions. For example, there is Coral Riff, whose “minions” are for all likelihood its many tentacles, which can move independently of its head.

The player does not fight the bosses in any pre-arranged sequence. Rather, at the end of every zone, the game selects one of them and changes their challenge level according to the zone number that the player is in. This is generally the case, unless there is condition-dependent scripting which imposes a specific boss on the player.

The challenge which a boss poses depends on a mix of factors. The variety and numerousness of their minions are factors, to name a couple of examples. The bosses may have more health in higher-numbered zones too. Regardless, after the player has learned the strategy to deal with a boss, defeating the boss at any zone would not be much different from defeating it in other zones.

TILES & WALLS:

In addition to enemies and hazards, the player should also keep an eye out for the tiles that the player character and enemies would be moving on, and the walls that the player would be moving by. Most tiles and walls are innocuous (in the case of the latter, where they are not Mimics). However, there are some which are inherently hazardous.

An example is the hot coal tile. This will injure anyone who stays on them for longer than one beat. Some enemies can generate these tiles and replace existing tiles with them, thus causing area-denial.

Water and tar slow almost anyone down, with the exception of huge monsters who can move through them without being impeded. Ice tiles causes the player character (and some monsters) to slide uncontrollably in the direction that they were moving to.

Most non-regular tiles can be removed, usually through the use of explosives/incendiaries. However, this is still consumption of precious resources that could have been used for other purposes (namely against enemies), so the player might want to consider this carefully.

SHOPS & SHOPKEEPER:

There is a trend in the design of rogue-lite games: it is the inexplicable presence of a merchant with random goods, setting up shop in the unlikeliest of places and whose only customers are the player characters. Crypt of the Necrodancer follows this trend, but also has plenty other entertainingly silly innovations.

The most obvious of these is that the merchant – called “Shopkeeper” in this game – sings. He can be heard as the player character approaches the shop, though there are other indicators which reveal its proximity too, such as golden walls.

Speaking of golden walls, the shop is ringed by them. Unlike the shopkeepers of certain other games, such as Splelunky, destroying the walls does not draw the ire of this game’s shopkeeper. In fact, he is perfectly alright with the player character collecting the gold from the walls and paying him with it. (This suggests that he did not build the shop in the first place.)

The entrance to the shop is usually a set of doors, but the procedural generation of the level may have the shop closed off entirely. However, one section of the golden walls is exposed and visibly cracked; this is an indicator that the shopkeeper has high-end merchandise. Destroying the wall is the premium which the player “pays” in order to gain access to the shop.

That said, the shopkeeper is there to take the player character’s gold, and the player should indeed let him take it; after all, gold is not kept between runs.

Alternatively, the player could try to kill him and steal his goods. This is not a decision to be taken lightly; the shopkeeper is tough and can deal far more damage than most bosses. Moreover, if he is killed, he will not appear in subsequent levels, thus depriving the player of the means to dispose gold for other gains.

Cunning and wily players have learned that the shopkeeper can be driven or lured away from his shop, e.g. by tricking a nasty enemy to bust into his shop and hurt him, or aggravating him and luring him onto a trapdoor. The current shop’s items will then become available for the taking, like they are regular loot, but the shopkeeper would return in the next level, none the wiser.

The shopkeeper, enigmatic as he is, may appear in other forms. In most of these cases, he changes the colour of his robes and sells goods of specific kinds. However, to encounter him in these other forms, the player needs to find hidden portals by breaking down suspicious-looking walls.

For example, finding a red rune underneath a wall leads the player to a variant of the shopkeeper who demands hearts instead of gold for his merchandise, which tends to be powerful items.

OTHER PROVIDERS:

In addition to the shopkeeper, there are other individuals which provide services other than selling goods. Like the shopkeeper’s other forms, they have to be reached by finding hidden portals.

For example, there is the Transmogrifier, which, for a fee, can change one of the player character’s gear pieces into something else of the same type. As another example, there is the Pawnbroker, who buys the player’s goods instead of selling any himself.

Perhaps the most desirable of these other merchants is the Dungeon Master, who can appear in a level as the merchant of a “secret shop”. He has only one item for sale, but it is usually very powerful and cheap.

SHRINES:

Shrines are intended to have the player make decisions of making quick gains at the cost of long-term setbacks.

Shrines can be activated in order to grant some gear to the player character; these gear pieces would be useful if the player character has yet to obtain any good gear. However, the shrine also makes the run tougher, often through introducing circumstances which are detrimental to the player’s efforts.

For example, the Shrine of Peace grants the player character additional heart containers, but at the cost of removing most of the player character’s existing gear. (This setback would later be pared down in the Amplified DLC.)

Alternatively, the player could have these shrines destroyed with bombs. This seemingly sacrilegious act does not appear to provoke any retribution though. Rather, the player is rewarded with trinkets from the shrines. Returning to the example of the Shrine of Peace, it releases a Ring of Peace, if it has yet to be activated.

Greedy players who destroy Shrines after activating them are rewarded anyway, albeit to a lesser degree. Back to the example of the Shrine of Peace, it releases a scroll when it is destroyed after being activated.

PLAYER CHARACTERS:

Cadence, Octavian and Cadence’s forebears have been mentioned already. There are other player characters, each of which with their advantages and disadvantages.

For example, there is Eli, who is Cadence’s uncle. He has an infinite number of bombs, and he can also kick them after planting them. (This effectively makes him an in-game reference to Bomberman.) However, he cannot use any weapon at all.

For some characters, their disadvantages outweigh the advantages that they have, thus making them strictly for players who are challenge-junkies. One example is Coda, which is the character with the most unlock requirements; Coda is also the most gimped.

CO-OP:

The player can play with another person, though in the DRM-free version of the game, only local multiplayer is possible. (Apparently, this is the case for the Steam and console versions too.)

Both players share the same beat rate, which is perhaps just as well because both of them would be listening to the same music.

Both players only lose when both of them lose their characters. As long as one player character makes it to the exit staircase, the other character is restored on the next level. In fact, if one of them gets onto the staircase while the other is nowhere nearby, both players are sent to the next level. This can be used for some strategies, such as having a player draw away enemies from the exit while the other sneaks by (which would be useful if they are both playing as the Dove).

The other player can choose to play as a character that is different from the main player’s. Interestingly, if both players choose to play as Cadence, the other player would be “Choral”, a dark-skinned version of Cadence but who otherwise has no presence in the story.

(Speaking of which, many unlockable characters have no presence in the story either.)

Unfortunately, there does not appear to be any palette swaps for the other characters for the purpose of co-op play with the same character, even in builds up to early 2016. This can result in some confusion, especially when the player characters mingle in close proximity.

There may be a problem with either player playing as the Bard. This is because as long as one player is the Bard, the beat tempo is replaced with the Bard’s; this applies to the other player too, even if he/she is not playing as the Bard. Whenever either player moves, the monsters get to move too. Therefore, the monsters are essentially moving at twice their usual rates.

(Alternatively, the player that is playing as the Bard can deliberately have him run off to his death, leaving the non-Bard player to play with the Bard’s tempo. This can be an incredible advantage.)

The biggest problem with local co-op is that the screen will not split in order to accommodate the separation of the player characters. The screen will expand and stretch in order to cover the distance between them, but this is a sub-par solution.

SLOW LAUNCH LOADING:

When the game runs, it runs quite smoothly. Level loading is quick, and thanks to the game’s use of simple PNGs, the graphics of the game are stable (if typically pixelated).

However, there is a problem with starting the game itself. It takes a long time to fetch and load its assets into memory. This problem has yet to be addressed even by version 1.27 (which is released together with the Amplified DLC).

VOICE-ACTING:

The voice-acting is the next aspect of the game’s sound designs that the player would hear upon starting the game for the first time. The most involved voice-acting is reserved for the story-related cutscenes, which is just as well because there is little story-telling in other parts of the game.

Most of the voice-overs are made with convincing effort, or are at least convincing at being deliberately over-the-top. When player characters dig walls or strike enemies, they utter grunts and battle-cries, which become more energetic as the beat multiplier goes up. Injury elicits groans from them, thus alerting the player if the visual indicators are not enough already. Then there is, of course, their exaggerated exclamations of despair when they die.

Interestingly, there are voice-overs which can be heard when the player is in the Lobby too. Stepping into a room in the lobby has the player character greeting the NPC in it, and there are several variations of greetings for each player character too.

VISUAL DESIGNS:

The pixelated retro aesthetics of the game would be obvious right from the start, even during the cutscenes. The cutscenes have had a filter applied on them that gives them a pixelated look, akin to the artwork which was used for the cutscenes in old games of yore.

Of course, the retro effect is not entirely convincing because the game’s graphics do take advantage of present-day technological advances, which is perhaps a good thing. Screen transitions are very fast, and the game can maintain consistent frame rates. There are no noticeable slowdowns, even when there are plenty of enemies with different animations.

Where possible, the artists of the game try to inject elements of musical instrumentation into the designs of the monsters. For example, Minotaurs have lyre-like decorations in between their horns. (The strings are not used in any way though.)

The artists had made certain that everyone looks like they are enjoying the music. For example, skeletons shake their vertebrae every other beat. Even the dragons nod their head to the music.

Unfortunately, the variety in the sprite designs of the player characters can seem disappointing in comparison to the variety in the sprites of monsters. All of the player characters appear to have the same general body shape, the orientations of their faces are all the same (perhaps with the exception of Coda), and all of them have the same hoppy dance.

Attack animations are sparse. The player would see the visualization of claw strikes when monsters land hits and white flashes of blade swipes when the player character attacks, but that is all. Only a few monsters have additional attack animations, such as the Dragons’ breath attacks.

DISCO EFFECTS:

Most of the things to be seen in this game may be pixelated and blocky, but as mentioned earlier, there is utilization of present-day graphical techniques. One of this is the application of colour filters that give the appearance of disco floors to the dungeons. To elaborate, as the player maintains a beat multiplier, the floor tiles of the dungeon exhibit an alternating checkerboard effect, which is noticeable enough yet perhaps not too dazzling for most players.

SHADOW EFFECT GIVING AWAY PRESENCE OF HIDDEN ROOMS:

Generally, most hidden rooms are obscured from the player’s view until the player character stumbles into them. However, there is a visual effect for shadows and lighting on walls that can be observed by the player in order to spot the presence of hidden rooms. This visual effect is the slight illumination of the south side of a wall that is the top boundary of a hidden room.

SUMMARY:

For players who love to “git gud” and who do not mind the risk of repetitive stress injuries, Crypt of The NecroDancer would be a great game to show that they have something to prove. Players who are curious of the hybridization of gameplay genres would also discover that The Crypt of the NecroDancer is a very fun example, though it does require more dedication to its gameplay than one would think.