With the demise of Strategic Simulations, Inc., it would seem that the future of digital strategy games based on Games Workshop's Warhammer 40K label is bleak. In fact, the line of previous strategy games based on this dark sci-fi franchise did simply slip into obscurity, for a time.

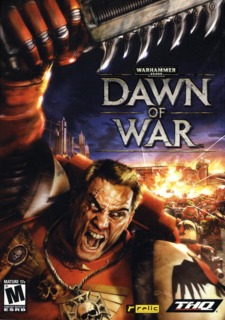

THQ, which is apparently eager to tap into video game niches that had not been filled, has applied for and obtained a potentially lucrative license from Games Workshop for digital games based on Warhammer 40K. Deciding that an RTS game would do what the mostly turn-based strategy games of yore had failed to (e.g. becoming commercially successful), THQ has picked Relic Entertainment (one of its subsidiaries) for the utilization of this license.

Considering Relic's portfolio of space-based strategy games, an ardent follower of Games Workshop's products may have expected that Relic might make a game based on Battlefleet Gothic, the space-based branch of the Warhammer 40K family tree of "specialist" games. However, perhaps to the dismay of those who know about Relic's less successful entries in its portfolio (namely Impossible Creatures), it has decided to make a ground-based real-time strategy (RTS) game instead.

The result is not an entirely terrible piece of work of course; much of the game functions very well and there are no serious technical issues, as to be expected of a Relic product. However, as it would turn out, Relic is not that good at paying tribute to source materials when it is working on products that are not entirely original and of its own making. Relic's followers would also be reminded that it is not so dedicated enough as to discover and work out minor issues in the gameplay, and if it did, the solutions further add to the impression that it is sacrificing canonical adherence for gameplay convenience.

Dawn of War starts with an intro that is apparently quite far removed from what one would expect from a Relic game (at least at the time). Unlike previous Relic games that resorted to concept artwork and voice-overs to present the gist of the game and its story mode, the intro of Dawn of War is a CGI movie. It is certainly awesome to watch and captures the themes of Warhammer 40K quite well, of course, and if Relic had intended it to present a first impression that it is doing something different with Dawn of War, then it certainly achieved its goal.

After the intro, the player is sent to the main menu, which is partly rendered by the game engine. This means that the game has to spend time loading up part of the game's graphics when it is executed, which can be a bit irksome if the player does not take kindly to games that waste his/her time just for cosmetic purposes. On the other hand, this pre-loading of some of the graphics does help the player in using one feature of the game, which is to customize the cosmetics of units for purposes of display in multiplayer, but this is a very minor feature.

The main menu gives the player the usual choices to be expected from an RTS game: there are tutorial, single-player story, skirmish and multiplayer modes, nothing especially new. Most players would be advised to consider playing the tutorial first, as Dawn of War has many sophisticated mechanics, which while not new, are uncommon in the RTS genre at the time.

The tutorial is fully voiced-over, a reassuring male voice telling the player of the significance of the fundamental designs of the game. The tutorial is very hand-holding though, removing away a lot of the player's control to lead the player towards taking that single action that the tutorial is describing.

The game has up to four factions that can be played. While they are thematically different and have different unit designs, they play fundamentally the same. Upon selecting any faction for play (with the exception of story mode), the player is expected to perform scouting, build bases, capture resource nodes, raise an army and purchase upgrades for said an army, and sallying forth to do battle with the enemy. The ideas behind the gameplay would be nothing new to base-building RTS veterans.

In game modes other than story mode, the player starts with a base headquarters building that will become the incubator for the rest of the base. It creates basic units, including worker units that would be needed to build other buildings; it also has to be upgraded to unlock branches of the tech tree. This is nothing that would surprise veterans of RTS games, of course.

At first glance, the four races in the game would seem to conform quite well to their canon. This is worked into the game in the form of minute differences in their designs to give them special advantages, which are in turn balanced by deliberate design gaps in their advanced tactics.

The Space Marines are generally very tough, and most of their units are capable in both close combat and ranged exchanges. They are versatile, but they are usually outnumbered by their enemies.

The Orks rely on their natural brutality and toughness and their numerous numbers to overwhelm their enemies, so this is represented in-game in the form of cheap but tough units that excel in close combat but are otherwise terrible at ranged combat.

The Eldar depend on speed, stealth and finesse for surgical strikes. This is reflected in their army designs, which are oriented around fast units that though weak, can hit hard and ruin enemies if the latter cannot develop a strategy to outmaneuver the Eldar.

The Chaos Space Marines (or Forces of Chaos) are depraved and cruel monsters who traffic with even worse beings. This is reflected in their ability to wreck the courage of enemies with dastardly inhuman powers and boons from fickle deities that grant the help of daemonic allies.

However, upon closer examination, a Warhammer 40K fan may notice the numerous liberties that Relic has taken with the canon. The first of these is the implementation of the headquarters building, which goes against the canon of the franchise.

While it may be acceptably characteristic for the forces of Chaos and the Ork hordes to establish headquarters on worlds that they intend to conquer and keep, this is actually more of the exception than the norm. As for the Space Marines and Eldar, this is completely not within their space-faring and/or nomadic character, especially not considering the history of the Blood Ravens (that have since been canonized as a Codex-following Chapter, meaning that they don't build bases) and the personality of the Eldar of Biel-Tan (which rarely, if not never, establish holdings on worlds that they visit their wrath upon).

Such designs would suggest that Relic has not really done much research into the thematic designs of the Warhammer 40K franchise, and if they had, then they certainly did not follow the canon accurately. This suspicion becomes even stronger when the player discovers that these headquarters buildings can be upgraded into structures with names that are associated with buildings and estates that canonically are not supposed to be simply plonked down on the battlefield only to be exposed to the attention of the enemy.

For example, Space Marines who follow the Codex Astartes (an apocryphal code of conduct) are definitely not foolish enough to establish Fortress Monasteries at every battlefield that they go to. Craftworld Eldar are also not prone to simply summoning in their precious plastic-like material, called wraithbone, just to build edifices that are very much exposed to violation by their enemies.

This canonical affront would be too much for a die-hard fan of Warhammer 40K to take, but for anyone else that is more tolerant, there is a very functional and sophisticated game to be had from Dawn of War.

Dawn of War adheres to the tradition of implementing a resource system to control the development of a player's forces. These resources are Requisition and Power, and in essence are not much more different from the gold and lumber or equivalents used in Blizzard RTS games and other games inspired by them. They are even obtained in fundamentally the same way: the player has to build or secure and develop resource nodes that yield them. For the gaining of Requisition, the player has to locate Strategic Points and build nodes on them, whereas to gain Energy, the player simply plonks down Power Generators close to base.

These resources are then expended to perform the usual tasks that players would do in RTS games, e.g. raising armies, building more bases and purchasing upgrades. Of course, this is also far removed from Warhammer 40K canon. Relic tries to concoct excuses to associate them with the canon, such as the excuse that holding territory would curry favour with the fictional benefactors that are supplying the player's forces with arms and troops, but this would not be convincing any Warhammer 40K fan that is well-versed in the canon.

If there is any refreshing design to be found in the implementation of these resources, it is how the nodes that yield Requisition points have functions other than to just sit still and generate resources. These nodes, called "Listening Posts", reveal nearby territory by removing the fog-of-war (fittingly enough, considering their name) and defend the Strategic Points that they are sitting on with automated weaponry (not so as fittingly). They can also detect cloaked units, practically becoming a no-go zone for any player attempting to infiltrate commandos behind enemy lines.

Once fully upgraded, Listening Posts can be very difficult to remove, and also make very good fall-back locations. Even low-level Posts can be used in meaningful, if rather cheesy ways, such as simply locking a captured Strategic Point by plonking down the pre-fab package for the building onto it but directing the worker unit to go elsewhere where it is urgently needed.

The Listening Posts appear to be functionally identical across the four races in terms of weaponry: all of them appear to be armed with rapid-firing weapons that are effective against infantry units, which are the only units that can capture Strategic Points and Critical Locations (more on the latter later). It can be a bit disappointing to know that Relic hasn't made much use of the thematic diversity of the four races to differentiate them in terms of gameplay fundamentals, but then these structures are not really within Warhammer 40K canon.

As for the Strategic Points, their names appear to be a misnomer, due to designs that prevent any Strategic Point, or collection of Strategic Points, from becoming a cause for gameplay imbalance if a player gets to control them for too long.

Strategic Points - and Critical Locations - that are continuously held will have their contribution to Requisition gain degrade over time, dropping to their lowest after 15 minutes; the game will notify the owning player of this, but not any other player. Therefore, this reduces their value for the owning player, at least until he/she loses said territories and successfully recaptures them again (which would be no easy feat).

(The same degradation also applies to Power Generators, the power contribution of which will degrade over time if they are not destroyed by the enemy. Attempting to exploit the system by destroying Power Generators with self-destruct commands and rebuilding them does seem to work as a cheesy work-around though, especially considering that the player can only make up to six of them at any one time.)

In addition, the squad capturing a neutralized Strategic Point or Critical Location, or removing ownership of an enemy-held Point or Location, has to focus completely on doing so; having them move away from a Point that is only halfway-captured, either by the volition of their owning player or being outright slain by enemies will cause said Point to revert to neutral state very quickly.

At first, this may seem acceptable because the design convention of having units doing something important at the expense of anything else, including defending themselves, had been around for a long time. They may even seem visually impressive due to the amusing animations that units have when they are performing a capture, such as the Orks' synchronized thumping of the ground.

However, it would seem odd to the discerning player that these battle-hardened or otherwise trained individuals would completely let their guard down just to plant a flag and wait for it to be completely raised. This thematic oddity would seem even more glaring to fans of Warhammer 40K lore, who would know that these soldiers, warriors or otherwise violent brutes will not indulge in such silliness when battles rage around them.

Furthermore, Strategic Points are very rarely located at any locations that can be considered strategic. They are often exposed to enemy fire and there is often no cover nearby to utilize. Only a few of them are wisely located on chokepoints, where the presence of a heavily armed and armored Listening Post can be especially useful.

However, there is a reason for the open space. Listening Posts project a zone of expansion that allows the owning player to build additional buildings in the vicinity, practically making the Listening Post the heart of a forward base. Making use of Listening Points to apply pressure on the enemy is far more economical than building new Headquarters buildings (which also project expansion zones, albeit these are bigger), though Listening Posts do not have the convenience of being much less predictable in placement across a map.

Even if a player prefers to build new HQ buildings anyway, the increasing resource costs needed to build each subsequent HQ building will deter the player from abusing said convenience.

It is worth noting here that in game modes other than story mode, the player generally starts with a scouting squad, free of charge. This scouting squad is lightly armed but fast, so it is best used to secure nearby Strategic Points instead of harassing the enemy at the start of the match (though, of course, this is up to the player to decide).

The tutorial will also describe the main designs about units in the game, if they are not obvious to the player already. Units operate as squads, moving as a group of individuals, each with his/her/its own health counters and damage output. As long as one member of the squad remains, the squad can be reinforced to full capacity, though not without cost. (There will be more on the mechanic of reinforcement later.)

Units operating as squads are not a new design in RTS games, of course. On the other hand, it is rare in games built with 3D engines, but this is not perfectly done in Dawn of War.

In games with 2D engines, the game designers have a cheaply convenient way to have squads navigating through rough terrain: they merely have the sprites sliding over terrain features and chalk this visual oddity up to limited graphics processing technology. Games like Dawn of War does not have the same excuse, and resorting to model clipping would lead to a lot of criticism.

Yet, these games are not perfect at having members of squads keep up with each other, e.g. there would be one or two individuals who get caught in terrain or get confused when their path-finding scripts blunder. Dawn of War is unfortunately not an exception.

Members of a squad being left far behind is a very rare occurrence, of course, thanks to pathfinding scripts that have other members of a squad swerving around an obstacle if one of them meets said obstacle. Yet, this clever work-around would have been convincingly splendid if squad members are all homogeneous, but they are not necessarily so. Members of squads may have different weapons or may be completely different individuals, and they run the risk of being left behind by the rest of the squad if they get caught in terrain.

Fortunately, Relic has thought of this, so it has implemented a form of rubber-banding to make sure squads stay as physically coherent as possible. Anyone left behind will get speed boosts that seem to be proportional to the distance of separation, allowing him/her/it to catch up with their squad-mates. If the stragglers are still left behind anyway (an even rarer occurrence), they are simply teleported over to their squad.

Of course, these compensatory measures require some suspension of belief, even more so if the player is an ardent follower of Warhammer 40K.

Perhaps the biggest hole in the squad-based unit designs of Dawn of War is the lack of formation options. Squads can be upgraded with squad leaders or attached with special characters that enhance the combat prowess of the squad, so the player may want them to take up tactical positions within squads so that they take the brunt of enemy fire first, screen them with other members or any other consideration about formation. Unfortunately, as the player is not given the options to micromanage formation, the player is not able to utilize these different squad members. (There will be more elaboration on squad leaders, special characters and squad members with special weapons later.)

The lack of formation options appears to be somewhat compensated by the mechanic of "Stances". However, Stances actually control the behaviour of a unit, and has nothing to do with positioning as the phrase "Stances" would suggest.

As an RTS veteran would expect from AI-scripting of unit behaviour, Stances set a unit to adopt various options for autonomy, such as having the unit aggressively going after any enemy that they come across, holding the area that they are currently defending against any enemy intrusion, or simply standing where they are if it is not prudent to have them moving around too much.

However, some other AI-controlling options may seem unfamiliar to said RTS veteran, as these happen to be unique to Dawn of War, or are at least rarely seen in RTS games. These other Stances will be described later, as they are best mentioned after more fundamental designs of the game have been mentioned.

Returning to the tutorial, the game will inform the player of how to raise armies after having secured some sources of income. The methods of gaining new units would seem plenty familiar to RTS veterans: build some unit-producing buildings, place purchase orders for units and wait for their arrival.

Again, Warhammer 40K enthusiasts may not take kindly to this, because these unit-producing buildings are based after edifices in the Warhammer 40K universe and these edifices do not canonically churn out units like product factories. They may also take exception to the naming of purchasable upgrades for units. Nevertheless, such designs work, because Relic apparently has decided that Dawn of War should not conform too much to the canon.

The player's army is likely to be initially composed of core units, which Relic has included in the game as part of its adherence to Warhammer 40K canon. Core units are initially just squads with relatively durable members that can be used to hold ground and take fire for while, but will eventually have a lot of customization options that are made available as the player unlocks more of the tech tree; these options allow them to take on anti-armor, anti-infantry or anti-heavy infantry roles, without losing too much of their ability to hold ground.

However, core units also cause the four different races to play somewhat similarly during the start of any match in modes other than story mode. For example, there is not much difference between the Space Marines' Tactical Squads and the Eldar's Guardian Squad, other than statistical differences and some minor abilities that alter statistics instead of having unique tactical value. (The former has higher hitpoints, while the latter can run faster temporarily.)

There would not be much excitement in the first minute of a match until players start on their build strategies for sure. Of course, one can argue that this is the norm in RTS games, but this also means that Dawn of War doesn't try to do something different, which can disappoint the more jaded of RTS veterans (and especially those who know about how Warhammer 40K games are conducted).

Once the player gets the options to customize core troops though, the gameplay certainly becomes very different from the norm. These options allow one or more members of the squad to be armed with weapons that are different from those used by their compatriots. The change is permanent, though it is lost if the squad member is slain. Yet, this loss also gives the player an opportunity to purchase another option.

(This is a stark contrast to the rules that govern special weapons in the table-top Warhammer 40K games, which assume that a regular squad member would pick up said special weapon when his/her/its compatriot is slain and which prevents players from switching special weapons mid-game.)

However, there would be times when core units are not satisfactory enough for certain situations. Therefore, the game has other units with specializations in combat roles, and which happen to be very good at said roles. The player can choose to fill some of the finite space within his/her army (more on the unit limit mechanic later) with these units instead of core units, though at the risk of facing situations in which these units are not up to the task. In situations where they are handy though, they can deal damage worth many times their resource costs.

For example, a couple of enemy core units that have taken cover in craters are vulnerable to rushing from close-combat specialists, such as the Eldar Banshees. The same Banshees are however not so effective when matched against enemy close combat specialists, especially when outnumbered.

Almost every type of unit in the game has a morale counter, the design of which would not be unfamiliar to veterans that have played sophisticated strategy games that try to simulate the stress of war on soldiers.

The main way for a unit to lose morale is to come under fire: all weapons damage morale in addition to health, though to a far less degree in order to balance the design that the morale counter of a unit is usually lower than its health counter. They can also lose more morale if they suffer casualties.

When the morale of a unit dives below a certain threshold (usually a quarter of its initial level or less), the unit "breaks" and suffers a tremendous debuff, which makes them vulnerable to any further pushing. They can regain morale if they do not take any further damage, eventually losing the debuff when they regain morale past said threshold (if they survive). It should be noted here that units that are taking cover in terrain features that grant defensive bonuses regain morale even faster, which is a certainly believable design.

However, unlike many other RTS games that implement morale systems, the player does not lose control of said broken unit; it only suffers the aforementioned debuff, but nothing more. It can still be controlled normally and its abilities can still be used. This is a refreshing change from the usual consequences of the implementation of morale systems, especially for players who are frustrated with losing control over broken units.

On the other hand, the benefit of the usual morale system, which is forcing numerically superior enemies to retreat prematurely before they can bring their advantage of numbers to bear, is absent. This means that the numerically superior army is still likely to win the day as long as the player can micromanage them, e.g. rotating units and using their abilities at opportune moments.

The morale system is also used to differentiate the different races' units from each other. For example, Space Marines, being diligently trained super-soldiers that have been enhanced for severe combat, generally have the best morale capacities, whereas the Eldar, though not cowards, are not used to having very heavy fire coming their way and will buckle under suppressive fire. It is also used to differentiate some weapons from the rest, such as Flamers (flamethrowers) being more effective at reducing enemy morale than other weapons.

The system is also used to implement some handy abilities, such as the Space Marine Veteran Sergeant's ability to Rally his squad, completely refilling their morale and possibly allowing them to fight to the bitter end at their fullest capability.

It is inevitable that squads will take casualties as they partake in battle this game. However, as mentioned earlier, as long as one single member in a squad survives, the whole squad can be replenished. This design would not be new to strategy game veterans of course, though the quirks and details of this design would be.

Unlike many other strategy games that have squad-based units, Dawn of War does not have any unit experience system. Therefore, the potential value of a unit is the same throughout a match, regardless of how many enemies it has vanquished (which the game still tracks, unnecessarily enough). Furthermore, casualties require resources to be replaced, so taking casualties will still cause the player to lose out economically. For some units, like Space Marines, the cost of each replacement may be higher if it is obtained via reinforcement than if it is obtained through purchasing the squad from scratch.

These designs would suggest that the player can just recruit squads, fill them out to capacity and fully upgrade them before sending them to their painful deaths while trying to have them take out as many enemies as possible, hopefully paying off many times their cost. This is fortunately not the case, thanks to a couple of subtle and simple compensatory designs that prevent such bloody economic exchanges.

Firstly, replenishing depleted squads is faster than raising a completely new one. Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, reinforcements – and unit-specific upgrades – can be gained by the depleted unit on the spot, without having to return to base.

The second bit can require a lot of suspension of belief on the part of the player, but it does have the advantage of convenience for the player. Unfortunately, it can also make battles cheesy, because most players are likely to jam away on the Reinforce button (or even automate it; more on this later) to summon in replacements to stretch the battles for as long as possible until other units get in place.

Almost all units in the game can be upgraded with squad leaders, which are individuals that are far tougher than anyone else in the squad and which increase the squad's morale capacity. He/She/It also grants the squad some additional capabilities, such as the Space Marine Veteran Sergeant's aforementioned Rally ability. Therefore, the squad leader becomes the mainstay of the squad, though as mentioned earlier, he/she/it can suffer from the game's less-than-satisfactory path-finding AI. The loss of a squad leader also causes a massive drop in morale.

Not unlike other competently designed RTS games, Dawn of War places limits on the size of the player's army. This is implemented in the game in a couple of familiar ways: there is the familiar construction of army-cap-raising buildings, and paying of premiums for the raising of caps. The latter is very straight-forward and has no risk whatsoever, because the caps cannot be lowered in any way after the fees have been paid.

The former would initially seem typical and perhaps even dull to a jaded RTS veteran. However, any impression of these buildings being simple "farms" would dissipate when the player discovers that they have other functions than just sitting still and becoming targets for raids that are intended to wreck the player's army cap.

The Eldar's Webway Gate, which increases their army cap, allows them to move entire armies across the map, though the process is fortunately not instantaneous, as it would have been overpowered otherwise, considering the Eldar's kind of firepower that excels at hit-and-run attacks. Late into a match, when enemies would have large armies that can be split to suppress the Eldar's ability to move across the map, the Eldar player has the option of upgrading Webway Gates with cloaking (awkwardly called "Infiltration" in the game) to force the enemy to spend resources on units which can detect cloaked units.

The Orks have population cap designs for its infantry that are a bit different from the others. Unlike the others' population cap designs that assign a number to each infantry squad, the Orks' population cap is governed by the actual number of Ork individuals and the quality of said individuals. The average Orks take up 1 slot each, while the bigger and more fearsome Orks, including the Ork Commanders, take up two. The Gretchin workers have their own caps.

The Orks' Waaagh! Banner, which increases their Ork population cap and also vehicle cap, also doubles as their static defences. However, while there appears to be a hard limit on the Ork population and vehicle caps, there is none on the number of Banners that can be built. In contrast, the other races have limits on the static defences that they can build.

This means that an Ork player can litter any zone of expansion in the map with Waaagh! Banners and upgrade them to have better weapons, making these zones particularly powerful strong points. This is a very expensive tactic of course, but it gives an Ork player that has achieved economic momentum ways to prevent that momentum from ever being lost.

However, Banners are actually quite easy to bring down, and Ork players run the risk of having their population caps damaged if their Waaagh! Banners are steadily brought down.

Regardless, a wily Ork player may be able to sustain the number of Banners, and even accelerate their accumulation in order to achieve an advantage in population caps earlier than his/her adversaries. This is where a resource unique to the Orks comes in handy to balance this, and it is simply called the "Ork resource", symbolizing the number of Ork recruits that are available for hiring as troops for the Ork player's horde.

Unlike the other resources, "Ork resource" is gained independently of any means and automatically. It has its own gain rate which cannot be altered in any way (approximately 1 point for each second). The only control that the player has over it is the maximum possible amount of "Ork resource", which is exactly equal to the infantry population cap. Having more Orks on the field reduces the maximum, which only increases after the player suffers casualties. Purchasing upgrades permanently reduces the maximum.

Therefore, the size of the Ork player's army is held in check to prevent it from becoming too large for players of other races to handle (though the Ork player is generally expected to have a more numerous army all the time, if he/she is competent).

The Ork resource system is also used to craft a special mechanic for the Orks that grant their units bonuses when their total Ork resource costs go above certain thresholds. For example, an Ork squad, or "mob", that has Ork resource value of fewer than 5 has no bonuses whatsoever. A mob with higher value may gain bonuses to morale and health recovery. With the right buildings built, a certain population cap threshold breached and/or even the right Commander attached, a unit may gain better bonuses like increases to maximum health and movement speed.

Generally, the Ork player would benefit from having as large an army as possible, using up Ork resource as quickly as they come up, or at least before an excessive amount is hoarded.

As for the other races' static defences, they can build automated turrets that while not capable of stopping determined assaults, are definitely capable of stopping raids and other kinds of light attacks. Otherwise, they are good enough to delay a determined assault if elements of the player's army could not reach their location in time. All static defences can also detect cloaked units.

They can be "side-graded", with cost, to permanently alter their default weapons into those of another type. For example, the forces of Chaos' Heavy Bolter Turret can have its default Heavy Bolters (very powerful heavy machinegun that fires micro-rockets, for those uninitiated to Warhammer 40K lore) replaced with missile launchers, which are far less effective against infantry but more powerful against vehicles (and they can still scatter infantry around).

Certain armored vehicles can also swap their default weapons for other weapons. For example, the Space Marines' Predator tank is by default armed with anti-infantry weaponry, but can have its autocannon and heavy bolters replaced with lascannon (laser cannon, for the uninitiated) batteries, converting its role from anti-infantry to anti-armor.

All these conversions provide tactical depth to the raising of an army, namely rock-paper-scissors considerations. This is, of course, nothing new to the RTS genre of course.

Unfortunately, this swapping of roles of static defences and armored vehicles, together with the gameplay designs of certain special weapons that core units can have, is also where the game commits yet another sacrilege against Warhammer 40K canon.

For example, while lascannons are canonically designed to be used against armored targets, they are supposed to be devastating against any unarmored target, if there are no preferable targets nearby. Instead, in Dawn of War, they do little damage when they seem to directly hit infantry targets. There are other examples, such as the Eldar D-Cannon seemingly doing nothing significant against infantry when it is canonically a terrifying weapon that sends victims to a horrible eternity of damnation in another dimension.

Warhammer 40K has themes of heroism and notoriety, portrayed through particularly strong-willed individuals who would become either vaunted and valorous heroes or dreaded and utterly cruel villains. Relic has utilized these themes to design the mechanic of special characters called "Commanders".

To an RTS veteran, these Commanders would function more like super units than the "heroes" seen in RTS games, because they lack any experience system that makes them more powerful over time. As super units though, they certainly do excel. Most importantly, there are Commanders that can be obtained early in matches, and they can be used to either scout or harass enemies rather effectively, unless they are countered by an enemy Commander in turn.

Later in the game, the Commanders' other abilities would come into play more than their relatively high statistics compared to other units. For example, the Ork Big Mek is the only Commander unit that is capable of repairing vehicles, and he can do this much faster than the Orks' workers, the Gretchins. Other abilities have to be unlocked with the right upgrades, often obtained through fully upgraded HQ buildings or late-game buildings. For example, the Space Marine Force Commander's Orbital Bombardment has to be unlocked through the Orbital Relay, a very late-game building.

The most important of these abilities though, is the option to attach them to squads. Doing so increases the durability of the squad, with the disadvantage that they have to move at the same speed as the squad. Of course, this design is nothing new as it has already been seen in (albeit more obscured) earlier games like Kohan and its sequel. Nevertheless, this is a very refreshing design as it is rarely used in RTS games. However, it has to be repeated here that the lack of formation options makes their utilization in squads less convenient.

There are also lesser variants of Commanders, of which the player may obtain more than one, such as the Space Marines' Apothecaries and the Orks' Mad Doks (both of which coincidentally increase the durability of the squads that they are attached to). They are a lot weaker in comparison, but they are also cheaper and add versatility to the player's army.

The gameplay designs are not restricted to just the designs for the four different races. The maps in the game also play a role in the gameplay.

In addition to the aforementioned Strategic Points, there are Critical locations that can be captured

However, like Strategic Points, the name of "Critical Locations" is a misnomer. More often than not, they are often located in areas that are terribly difficult to defend, made all the more difficult by restrictions on building close to them. These Critical Locations also cannot be built upon with Listening Posts, compounding said difficulty. On the other hand, in skirmish and multiplayer modes, they are needed for a specific victory condition, as will be elaborated on later.

Relics are map features that any player – or team of players - would want to obtain and retain, as these unlock the more advanced branches of the races' tech trees. However, these are actually little more than Strategic Points that look different from the rest; the "Relic" label is really no more than another misnomer (and may have been included in the game due to less-than-concealed egomania on the part of Relic itself), and certainly doesn't resemble any relics in the Warhammer 40K universe. (These are either usually grand-looking – or very terrifble to behold.)

Regardless of canonical adherence, players may want to grab Relics anyway, if only for the advanced units they promise, such as the devastating Land Raider for the Space Marines. However, these units are exceptionally powerful; for example, the aforementioned Land Raider is a monster of a vehicle, being very durable. It is guaranteed to at least tie up any enemy unit that makes the mistake of engaging it for a very long time, if it does not drive them off. Some players may be apprehensive of Relic-enabled units and upgrades, so it is fortunate for them that Relic has included an option to disable Relics in skirmish and multiplayer modes.

However, if Relic-associated units and upgrades are to be included in a match, they can only ever be obtained by capturing and holding Relics. Furthermore, Relics are more difficult to defend than regular Strategic Points, as they appear to inflict a sight range penalty on the Listening Posts built on top of them, and they are situated in even more precarious locations than Strategic Points.

Peculiar map features known as "Slag Deposits" exist in some maps, but not all of them, as an alternative to the default method for the generation of the Power resource. Players do not need to capture these like they have to with Relics and Strategic Points, only that they have to build special generators over them, in order to gain their considerable bonus towards power generation.

Furthermore, these special generators do not have their value degrade over time, for a very good reason: they are often located in very difficult to defend places, more so than even Critical Locations and Relics. Also, despite the zones of expansion that they project, their placements in map are often such that nearby obstacles or even map boundaries prevent the player from making use of the zone of expansion.

The game does not describe how exactly "Slag Deposits" can generate power, not in the tutorial or in the story mode. In fact, they don't even appear in Warhammer 40K canon and may have been an original concoction of Relic Entertainment.

As mentioned earlier, Strategic Points, Relics and Critical Locations have to be captured before they can be placed under the player's ownership. This is where the developer introduces more differences between the four races, namely in how quickly they can capture or remove the ownership of said map features. For example, Space Marines, Chaos and Eldar are equally fast at taking points, but the Orks are slower at doing so, their canonical indifference towards taking care of whatever they have being the excuse for this difference. This is fortunately counterbalanced by the advantage that Orks have in fielding units.

Other map features that players are informed of in the tutorial and should learn more about are pieces of cover. Cover pieces are small regions within the map that have properties that usually grant defensive bonuses to any units which are cowering in them; both infantry and vehicles are affected. For example, there are craters that units can hide in, and they will visually show to on-lookers that they have said defensive bonuses with animations like infantry cowering down.

To prevent players from abusing cover too much, cover often inflicts movement penalties on units that are moving through them. This is believable, as cover like a bunch of rocks would make movement through them difficult. Another balancing design is that defensive bonuses cannot be stacked beyond 90% reduction of damage. Moreover, special abilities like grenades and Doombolt spells ignore cover completely.

However, the application of cover bonuses and how units use cover can be finicky and even frustrating. When a squad unit is told to cower within an area of cover, its members may not entirely enter said area; some may be mingling outside, and thus will not benefit from the defensive bonuses. Repeating the order may not solve the problem, as they may reorient themselves but still some of them would be left outside.

Some other pieces of "cover" actually have the reverse effect; they inflict penalties instead, though not necessarily on the affected units' resistances to damage. For example, marshes slow down units that are caught within them. Generally, it is not wise to move through them, but there are units that are not affected by certain negative penalties at all, such as Bloodthirsters, the Chaos forces' super-units, which are just too huge to be affected by puny nuisances like marshes.

In previous generations of RTS games, the player can often do little about buildings that have been built but are no longer needed by the player. By the time of Dawn of War, most competently designed RTS games give the player the option to cause buildings to self-destruct. Dawn of War is not an exception, and sweetens the deal by allowing the player to recoup some of the costs that have gone into building them. This does result in some cheesy tactics and exploits, but giving the player more options is always commendable.

Setting a build or purchase order to repeat itself in buildings has been a norm in RTS games for quite a long while, though doing the same within the control interface for units is a rarity beyond titles like Warcraft III. However, this can be done in Dawn of War, which is convenient considering that some units have options that would benefit from automation, such as reinforcement.

However, the tutorials do not teach this to the player, and the player would only know of this through the documentation for the game or (more likely) through third party sources.

The tutorials also do not teach, in detail, the more advanced of Stance options, which have been mentioned earlier. However, this is understandable as these options are meant for advanced players.

There is a Stance for a unit's autonomy to fire on enemies within range. This toggle seems to be useful if a player wants to have cloaked units slip past enemy lines, though Cease-Fire would already be automatically applied on cloaked units to prevent them from giving away their positions by firing upon enemies.

Another behaviour option has units targeting enemy buildings over enemy units. This is very handy for dedicated anti-armor units like the Orks' Tankbustaz, which also happen to be just as handy against buildings as they are against vehicles. Unfortunately, this option will also highlight the less-than-equivalent distribution of anti-armor units among the four races, as a player would found out when he/she learns that this option is more useful for races with easier access to specialized anti-armor units than for those that do not, such as the Space Marines.

(For the Space Marines, the earliest anti-armor capability that they can have is a Tactical Squad upgraded with Missile Launchers, but this means that the rest of the squad's firepower, e.g. their boltguns, is wasted when buildings are targeted.)

Units locked in close combat cannot use their ranged firepower, so the prudent player may want to micro-manage battles such that the enemy's firepower is neutralized by having units engage them in melee – even if the player's units that have been committed to melee are not really good at it. Therefore, it is very convenient that there is a toggle to have units prioritizing melee combat over ranged exchanges.

Some nuances of the game are not told to the inexperienced player, who will only learn of them through observation.

For example, when a large squad of melee-oriented units, such as the Orks' Boyz mob, attacks enemies in close combat as part of an Attack-Move order, the Orks will spread themselves out to engage as many enemies in melee as possible, including members from more than just one enemy squad. This means that particularly large squads can lock up more than one enemy squad at a time, a design which experienced players will use against clusters of enemy squads with ranged firepower.

However, the same player may learn that it is rather easy for units to disengage from melee; they just have to be given an order to run away and they will. While this may seem to encourage cheesy "kiting" tactics, this is counter-balanced by the fact that all units will regenerate health over time, making such tactics difficult to utilize without acceptable returns.

Another nuance in the game is that opposing Commanders will duel each other in close combat, even when they are attached to squads (which have engaged each other in close combat, of course). This prevents them from using their autonomously executed special attacks, such as the Librarian's staff-slam, which are effective against entire enemy squads. The Commander units can only regain the use of these attacks once their duels have been resolved, i.e. after one of them is dead.

Yet another nuance is that unlike many other RTS games, Dawn of War appears to be rather forgiving when transport vehicles that are loaded with infantry are destroyed; said infantry units simply reappear where the transport vehicles are destroyed. This is very convenient for an RTS game, though it has to be mentioned here that the table-top game of Warhammer 40K is not as generous.

One more easily overlooked design of the game is that it uses luck-dependent mechanics for deciding whether units hit their targets with ranged fire or not. Every type of unit has a percentage of accuracy that appears to decide whether they managed to apply damage or not for every firing cycle (each type of unit has its own firing cycle). Some weapons, under default conditions, are guaranteed to hit, such as flamethrowers. The others have accuracy of less than 100% by default. There are many factors that affect accuracy, such as firing on the move (especially) or the application of buffs and debuffs.

Unfortunately, having a luck-dependent mechanic means that players may suffer strokes of bad luck, such as a fleeing unit suffering an uncanny hit from enemy artillery, which generally should miss fleeing units.

Fortunately, accuracy matters far less, or not at all, where the use of special abilities is concerned. These can turn the tide of the battle, so it is fortunate (pun not intended) that luck does not have a role to play in these occasions.

Some other nuances are not so easy to utilize, even by veterans of the game. For example, there is the subtle game design that have units that are engaging in close combat also taking less damage to morale (and to health), apparently due to the cover provided by the mingling of bodies. Considering that said units are going to suffer damage anyway from the close combat and that it is probably wiser to have units retreat to more defensible places, a player would find this game design difficult to exploit if the player intends to preserve units.

A few of these nuances may also seem to be little more than glitches. For example, infantry can enter a transport vehicle and retain all of their buffs and debuffs, even after they disembark after a long ride. Furthermore, infantry continue to regenerate while embarked on a vehicle. This can be used for many exploitative tactics.

The player will also discover that vehicles have no capability to run over any infantry. Attempting to do so only causes said infantry to move aside, at the most causing their animations to be interrupted.

It should be apparent by now that while Relic has designed satisfactorily competent and sophisticated gameplay for Dawn of War as an RTS game, it has taken plenty of liberties with the canon and has overlooked many slight flaws. The gameplay alone would also not be impressive enough to a jaded RTS game veteran that is looking for something convincingly brand-new.

Therefore, one would wonder how the game would appeal to the very discerning game consumer. The answer would be in its presentation.

Although Relic may have disrespected the canon in the eyes of die-hard Warhammer 40K fans, it has successfully portrayed the themes of the Warhammer 40K universe, which are, of course, all about war, its horrors and its brutality.

Initially, the combat in the game may not seem impressive. Ranged units will exchange fire with each other, standing completely still while doing so and performing simple dying animations when they get killed by gunfire. However, combat becomes far more interesting to look at when they do something else.

As one example, almost all units will fire on the move if they are moving past enemies. This is not cosmetic, as damage will be dealt, though not as much as that would be dealt if the player had committed them to battle instead of running past. These running units, of course, cannot fire behind them if they lack any capability to do so. This is impressive to look at, though it has little gameplay value due to the reason mentioned just earlier.

When opposing units engage in close combat, they become even more impressive to look at. Every member in a squad will come to grips with at least one member of the opposing squad quite seamlessly. Initially, this would not seem refreshingly new to those who had already seen 3D models fighting each other in earlier RTS games such as Kohan and Battle Realms, but those games had major flaws in their presentation: units fighting in melee appear to be only performing their canned animations, regardless of the opponent that they are facing.

In Dawn of War, Relic had at least attempted to make sure that each participant in close combat appears to be reacting to their adversary's attacks, e.g. parrying attacks or staggering from having been hit. Of course, this would also seem to be nothing new to players that had seen similar programming for fighting animations in other games, such as Neverwinter Nights, but this was a very rare occurrence in RTS games at the time.

Perhaps the most impressive aspect of close combat is the coup-de-grace moves that individuals perform when they defeat their opponents. Each kind of individual has a few variations of such animations. For example, an Assault Space Marine may smack his opponent his down after slashing away with his chain-sword, or execute him/her/it with a bolt round in point-blank range after stunning an opponent.

Of course, a sceptical player would raise the question of individuals becoming vulnerable to enemy attacks when they are performing coup de grace animations. Relic has a practical answer for this concern, but it is rather cheesy: the individuals are merely rendered impossible to damage, even if they are being attacked. This can be exploited to delay the advance of enemies, such as sending a Space Marine Dreadnaught to murder very weak enemy infantry and thus draw the fire of any other enemy units while it is performing killing animations on said infantry.

However, Relic appears to have noticed this, so through a series of patches, implemented a probability-based system to govern whether killing animations occur or not in close combat.

There are also animations for units that are using abilities, and these animations do not appear to be repeated for different abilities (which were quite the norm in RTS games when the game designers do not bother with the diversity of the animations). The most impressive of these are those used by the Commander units in the game.

Heavy weapons are portrayed in manners that make them seem fittingly powerful. For example, lascannon beams are appropriately bright and briefly-occurring, as to be expected of lances of light. Perhaps the most dazzling weapons are those that belong to the enigmatic Eldar, which uses technology that no other race other than their own would be able to understand. Many of their weapons have unique-looking particle effects (and audio designs) that serve as tell-tale signs that the Eldar are nearby and are in combat.

As for the technical aspects of the game's visuals, they are actually not that advanced for an RTS game. Models actually have very few polygons, a convenience afforded by the visual designs of the warring factions in table-top Warhammer 40K, which needed simple-to-mould resin and metal models. The textures and decals on models are more sophisticated than their number of polygons, though the latter aspect of the models prevents the former from looking more impressive.

On the other hands, the animations are many and impressive, as mentioned earlier. Even the buildings are well-animated, rarely looking – and sounding - idle while they are processing a unit purchase or upgrade order. For example, drop pods falling down onto and Thunderhawk transports landing on the Space Marines' structures are a common theme in their visual designs. They do sometimes obscure the screen, but the animations are so fast that they won't be much of a visual hindrance.

The maps also portray the themes of the Warhammer 40K universe well. Most of them either consist of run-down civilization, such as the war-struck cities of the Imperium and the ruins of Eldar civilization when they were still mainly planet-bound, or are wild and/or desolate, such as planets affected by severe tectonic activity and jungle worlds. It is unfortunate that there are not many levels set indoors or in space, but the existing themes are adequate enough to present a thematic variety in the locales.

Perhaps even more impressive than the graphical designs of the models and maps in the game are its sound designs. The voice-overs for units portray their character and personality quite satisfactorily, such as the Orks' guttural and crude enunciations that befit the crass simplicity of their violence-addicted race, and the condescendingly contemptuous and haughty demeanour of the Eldar, who generally have a superiority complex for knowing that they belong to a civilization that once ruled the stars.

When enemies come into the sight of squads under the player's control, voice-over clips will play such that it sounds as if they came from said squads. This impression is further reinforced by specific voice-overs that say the same thing but with different voice qualities that are associated with said squads. A couple of the clearest examples of such audio designs can be heard in the voice-overs for Eldar units: a Guardian squad that encounters an Ork squad will make disparaging remarks on the latter in otherwise clear enunciation, whereas a Warp Spider squad will say almost the same remarks but with warbles to portray their less-than-healthy career as soldiers that make use of dangerous teleportation technology to get from one place to another.

There are also voiced-over warnings on the battlefield situation, though this would not seem to be anything different from earlier RTS games that have emphasized the thematic difference between warring factions. Nonetheless, they are still very much in character.

However, a player with a keen ear will notice that many voice-overs came from a stock few, only given variation through clever mixing and alteration of pitches. For example, the player may notice that the voice-overs for Obliterators are actually those for Chaos Space Marines, only with higher bass and more gurgling.

Adding to the din of battle are the sound effects and ambient noise. As to be expected of a game with sci-fi themes, there are plenty of noises that won't be heard in the real-world, such as the high-pitched discharge of plasma-based weaponry and zings of laser beams. Of course, there are still believable sound effects, like those for explosions, the booms of cannons and the rattle of automatic ballistic weapons. Then there are very peculiar sound effects, which can only be expected from a game that is based on Warhammer 40K, such as the whirring of chain-swords and the grinding of flesh when said weapons hit home.

Yet, despite the otherwise splendid portrayal of battles and war in the Warhammer 40K, Dawn of War does not perform a thoroughly good job at portraying the narrative qualities of the franchise. It will be quickly apparent to Warhammer 40K fans that Relic's writers (and hired writers) have calibre that is far, far different from those that work at Games Workshop HQ, or even Forgeworld.

The story mode concerns the oft-used overarching plot of a struggle against those that thrive on mayhem or are otherwise cruel, selfish and evil. There are no "good guys" in the Warhammer 40K universe, though this is not portrayed so well in the story mode as the player does not often encounter the need to make painful decisions that would sacrifice the few for the sake of the greater good.

For example, the main protagonist is leading a Space Marine taskforce that is attempting to contain a threat from an Ork Waaagh! and has no qualms about wresting command of local Imperial forces, but otherwise plays the role of an otherwise honourable war leader who would not waste forces under his command for no gain, which is often the exception than the norm for the generally canonically aloof Space Marines.

There are secondary plots of regret, redemption, delusions of grandeur and damnation, but these are often used as excuses for some scenarios in the campaign and for the padding of the story's drama. There is not much in the way of long-lasting gameplay consequences from diabolical plot twists, as these are quickly compensated by the appearance of opportunities to make things right or regain something in return for something lost.

For example, there is a critical moment in the story when a trusted ally turns treacherous enemy, but this loss is quickly replaced by someone who is equivalent in terms of ability.

In other words, a player should not expect a story mode that is different from those of so many other RTS games before Dawn of War.

Perhaps the worst that the story mode does is to highlight the limitations of the game engine. A player that zooms up close towards units would realize that the graphics of the game are not really impressive at such intimate ranges. However, Relic's game designers appear not to have realized this, and have used plenty of close-up camera shots for many cutscenes, thus exposing the weaknesses of the game's graphical designs, or more precisely, their lack of effort or skill.

The most terrible of these is the lack of believable facial animations. Most of the characters that are talking on-screen appear to have their jaws distending and contracting without any rhythm with the voice-overs. This makee them look comical, which is a detriment because they are supposed to be anything but. (Perhaps the Orks are an exception, but they do not get much screen time in the story mode.)

In other words, the experienced RTS game veteran should not be expecting much innovation from the story mode of Dawn of War. At best, it can be considered just decent.

The player would not be getting such trouble from the other modes of the game. The skirmish and multiplayer modes present the themes of the Warhammer 40K much more earnestly, though this is of course due to their not needing a story.

However, to experienced RTS game consumers, these modes would not seem to be essentially different from those seen in many other RTS games before. The total annihilation of the enemy is still the overarching objective, though this is not the only goal, if the host and his/her fellow players decide so.

This is where a minor mechanic involving Critical Locations and Strategic Points would come in handy for injecting some variety into the gameplay. Players can agree on enabling conditions that allow players, or teams of players, that control the majority of these map features to start a countdown that will automatically give a victory to the owning team if and when it reaches zero.

Critical Locations have the lowest threshold of them: the owning team/player needs only more than half of them in a map to start a countdown, compared to two-thirds for (the more defensible) Strategic Points.

Perhaps oddly enough for an RTS game, Dawn of War also features options for economic victories for multiplayer/skirmish matches. Players or teams who manage to amass tremendous amounts of resources can win the game outright, if they can survive the onslaught that would come after the game automatically notifies other players that they have managed to hoard resources close to the target amount.

Such victory conditions may seem to encourage "turtling" strategies, which are not exactly well-received by every RTS enthusiast, but such "take-and-hold" gameplay, associated with "king-of-the-hill" matches, adds to the variety in the gameplay, and more variety is generally not a bad thing in games. Dawn of War is no exception.

A team of players can also choose to share resources with each other, or go Dutch. Sharing would seem to be more strategically convenient and more potent, but to ensure that this is an option instead of a necessity, there are drawbacks designed into this option; the bigger a team is, the fewer resources they get from resource nodes.

Perhaps the greatest weakness of the game's designs for multiplayer is the Assassinate victory condition. For this condition, each player is given the toughest Commander unit available to the player's race; losing this character means that the player loses the game outright. This can be a problem to some factions, such as the Eldar, whose Commander unit, the Farseer, is not exactly as durable as the rest and thus may be at a disadvantage if she is forced to duel other Commander units early in a match (which is a very risky proposition).

In conclusion, Dawn of War is generally a well-done RTS game and is just as fun as any other competently designed RTS games of its time, if not even more so because it is very sophisticated. However, there are many mechanics that though functionally sound, have minor design oversights. Worst of all, as a Warhammer 40K-licensed game, it certainly does not do justice to the canon and takes many liberties with it for the sake of convenie