INTRO:

Indie game development always face the trouble of having terribly limited budgets; making do as much as possible with what is given or at hand is an ethos that has to be learned.

There had been indie developers that did quite well in this matter. Then there are those who do little more than take something from the proverbial shelf, polishing it and repackaging it.

Gemini Rue is an expression of the latter case, made all the more noticeable since it is published by Wadjet Eye.

DIFFERENT DEVELOPERS:

Followers of Wadjet Eye Games’ offerings may be quite familiar with Dave Gilbert and his works. He appears to learn about game development as he goes, so there are some games of his that are quite rough around the edges. However, whatever lessons that he learned, he applied quite well.

Gemini Rue is designed by an alumnus of a media design degree, as part of his undergraduate work. The adaptation into a “full” game shows – and not entirely for the better. Perhaps Wadjet Eye Games – and Dave Gilbert – believes that they are supporting indie developers by publishing games from budding creators, but closer examination of this product would have revealed that its design quality is very much different from those of Gilbert’s own works.

PREMISE:

The game is set in a space sci-fi future, where faster-than-light travel is possible. Its setting is one of those unhappy ones, where humanity live in a dystopia brought about by limited resources and lack of ethical oversight.

There appear to be two protagonists: Azriel is a cop that is looking for his brother, whereas Charlie is an inmate in a secret rehabilitation facility. The player swaps between the two player characters, getting clues to what they should know and what they should be doing to overcome their current predicament.

One of the clues suggests that the cop’s brother is in the same facility that the other protagonist is in. The game makes an attempt to have the player think that the two are somehow connected, though further details are withheld.

Veterans of story-telling might already know where this is going; for everyone else, the other clues foreshadow an outcome that the obvious is not always the truth.

The overall plotline is definitely not clumsily written. The problem, however, lies in its execution, specifically how the gameplay is crafted around it and the programming for the game.

AGS STUDIOS GAME:

Like Wadjet Eye’s other games, Gemini Rue is made with Adventure Game Studios (AGS), an engine that is intended to make games that are akin to those in the Sierra and LucasArts years. Thus, the game appears to have a lot of technical similarities with other Wadjet Eye titles.

Unfortunately, there are quite a lot of flawed designs in this game – designs that Gilbert would not use in his own games. These will be described shortly.

RADIAL MENU FOR ACTIONS IS SERVICEABLE:

The game makes use of a pop-up menu, which appears whenever the player right-clicks on something. This radial menu has icons for speaking to people, kicking things, handling them or examining them. This is similar to certain LucasArts games, such as Full Throttle, and it works just as well here.

RADIAL MENU FOR INVENTORY IS NOT:

However, the radial menu is also used for showing the inventory. There are no other means to bring up the inventory. Thus, the player would have to right-click on an object that can be examined or interacted with and that is in the scene in order to bring up the inventory.

Considering that so many other adventure games – including Full Throttle – have already done the established method of dedicating one edge of the screen or a shortcut key to bring up the inventory, the procedure in this game is tedious.

SHORT BUT TEDIOUS AREA TRANSITIONS:

Another tedious matter is the act of area transitions. Most adventure games at the time use hitboxes that are next to the edges of scenes or on obvious objects that are meant for transitions like doors; these hitboxes have tooltips that appear to indicate that they are area-transitioning objects. Players click on the hitboxes to trigger the scripts.

This game has these, of course, but not for every scene. In the scenes that do not have them, the player character must click on locations well into the edge of the screen, or well past doorways, in order to trigger the scripts. Furthermore, the player has to wait for the player character to move out of the screen.

One example happens early on in the game: the player character must open the main doors into an apartment, and the player has to click somewhere just past the open doors to get the player character to walk in.

MANY DOORS, AND CAN’T OPEN MOST OF THEM:

There are many, many doors in this game. Not many of them can be opened; in the case of those in Charlie’s chapters of the story, that they cannot be opened is understandable because he is in a facility with restricted access for inmates.

With a pair of lockpicks in Azriel’s possession, the inquisitive player would try to have Azriel open the locked doors that he comes across – only to have him refuse. In most cases, this is believable, such as when he is supposed to get somewhere soon and that he should not be distracted. On the other hand, he would spend time trying to check if anyone is at home behind the locked doors even though the doors are not the ones that he is looking for.

Some of these doors can later be opened, mainly because the same locale is revisited again in a later part of the story. There will be more elaboration on this later.

MIRRORED PUZZLES:

Apparently, the “Gemini” word in the title of the game is expressed through certain similarities between the puzzles that one protagonist handles and those that the other protagonist handles. For example, both protagonists will be having pipes in their inventory, typically to knock things down or nudge them when they are out of arm’s reach.

At other times, something that appears as an obstacle in one protagonist’s segment appears as just an aesthetic object in the other’s. For example, one protagonist has to make use of dangerous steam to overcome a threat. Meanwhile, the other protagonist passes by a steam hazard that is just barely out of the way.

This peculiar similarity is especially noticeable at the beginning and at the end of the game. The middle sections have less obvious similarities though.

These are there to foreshadow a certain plot twist, in case more overt clues do not suggest so already.

REUSED ASSETS:

Many scenes occur in the same place. This limitation is understandable for the scenes that occur in Charlie’s part of the story, because he is incarcerated. This is not so understandable for Azriel’s.

Of course, the creator of the game has the decency to admit that this has been done to save cost and reduce development time. However, in the case of the story-telling in Azriel’s part, this can seem lazy and even unbelievable.

For example, the player character would be returning to the same apartment where he had shot and killed several people earlier. Yet, the apartment is not under lockdown by anyone that has the authority or power to secure places for investigating who perpetrated the killings.

INCREDIBLE SERENDIPITY:

The world that half of the game takes place in is Barracus, which is a colonized world with what appears to be clearly urbanized places. One would think that the people that the player character has to meet might be scattered across the world, or at least in different districts.

Conveniently though, most of them happen to reside in what is practically the same neighbourhood, within or in the vicinity of two apartment buildings. This is, of course, an expression of reusing assets, as has been mentioned earlier.

One or two persons living close to each other may be a coincidence, but when the list grows to around half a dozen different characters, there is just mounting disbelief.

TRIAL AND ERROR / LOGICAL ELIMINATION PUZZLES:

There are some puzzles in which the player needs to resort to trial and error, because the clues to these puzzles are only clear in hindsight.

A notable example of these puzzles is getting a dummy load to fool a weight-sensing receptacle. This has been done before in the history of adventure games before, of course, but the caveat here is that the player has a few options for the dummy load.

Each option is associated with different weights, with no readily discernible clue as to which weight is needed. The new player has to go through the options one by one, retrieving a different dummy load each time if the previous one did not work.

The only plausible clue that point to the correct option is the weight of the object that the dummy load is replacing; this is only clear after the puzzle has been solved. The handgun, which is of an indeterminate model due to the pixilation, has a weight of four pounds.

Prior to knowing the correct weight, one would think that knowledge of handguns might be handy here, e.g. the most-used handguns are between one to two pounds (lbs) in weight, including when loaded. Indeed, there is a dummy load with this weight. Yet, the correct dummy load is actually four pounds.

Incidentally, four-pound handguns in real-life are large-calibre semi-autos like the Desert Eagle, and they were particularly prominent in video games. Thus, in hindsight, the player’s clue is that four-pound handguns were once a trend in video games.

Furthermore, four-pound handguns in real life can fire large-caliber bullets that punch through any cover that is not made of thick concrete or tougher composition. The ones in this game cannot do so. (There will be more on combat later – yes, there is combat in this game.)

Another example of a trial and error puzzle is trying to get the exact things to say to a certain smuggler. The player’s only clue is that the smuggler is an off-world person, and smuggles goods that are contraband on Barracus. These clues give enough info as to the person’s vocation, skills and available resources and assets, but the person’s motivation is not clear.

The player would have to go through each of the options that concerns the person’s motivation until the correct combination of options is obtained. This can be tedious.

There are a few more, none of them being any more sophisticated. They appear to be just there to “exercise the player’s mind”, according to the developer’s commentary.

INCONSISTENT MEMORY DURATION AMONG NPCS:

Some adventure games have the player trying to get the player character to say the right things to an NPC. The player has options that are not the correct options, and saying them would elicit a denial or refusal from the NPC. The problem with these NPCs is that they have short memories.

It would appear to an onlooker (or eavesdropper) that the player character is repeatedly pestering the NPC, who somehow lets this pestering go on until the player character says the right words. Understandably, these kinds of puzzles can seem silly and unbelievable.

Whimsical games like the Deponia series can get away with this because their characters are comical and may have hilarious responses. However, these puzzles undercuts the seriousness of the settings of games with supposedly mature themes.

Unfortunately, these puzzles occur in this game too. It can seem silly that one of the protagonists can repeatedly call a smuggler without the smuggler simply blocking the incoming calls.

GUNFIGHTS:

For better or worse, there is combat in this otherwise typical point-and-click adventure game.

Gunfights occur whenever someone exclaims that enemies are coming, or a shot from ambushers happens to miss the protagonists. This can seem convenient, of course, but the player has to be warned that a gunfight is coming up.

The player character is always alone. However, enemies may be on their own too, or in pairs; there are never more than two, apparently because the local opposition just so happen to be under-manned at the time. Again, this can seem rather serendipitous.

Furthermore, despite the clearly sci-fi setting (which includes humanity having obtained faster-than-light technology for space travel), the combatants are always armed with ballistic handguns (which apparently weigh four pounds). This can seem disappointing, though of course, the game was developed on a tight budget; hence the lack of any flashy sci-fi weapons.

TAKING SHOTS:

Anyway, the combatants take positions behind pieces of cover, which are always indestructible. To fire shots, they have to peek out of cover to fire. This also renders them vulnerable to being shot at.

In the case of CPU-controlled enemies, they always fire on cycles: they peek out of cover and empty their magazines. The player’s best bet at shooting and hitting them is to have the player character already aiming at them and firing as soon as they peek out.

The player could try to have the player character shoot when they are shooting, but generally this is not a good idea.

AIMING:

The player character has the advantage of being the only character that can land a guaranteed shot. To do this, the player can have the player character hold his breath; a meter shows how long he can hold his breath. At the limits of the meter, there is a region that indicates when a shot that he fires is guaranteed to land a killing blow, i.e. a headshot.

However, the player needs to time the “charging” of the meter with the moment when the enemy peeks out of cover. Any hits that the player character takes will immediately cancel the process.

TAKING HITS:

Any combatant that is hit immediately withdraws back into cover, if he is not killed. In the case of the player character, the first three hits are fortuitously superficial; he will not die from these, and there will be no lasting damage if he prevails. In fact, his “health” meter restores completely by the next gunfight. However, the fourth shot will kill him, and it will be game-over and a game reload.

As for enemies, they also take just about the same number of shots – unless the player is lucky enough to land a headshot. As mentioned earlier, aimed shots are guaranteed to land headshots, but there is a chance that a shot that is not aimed would land a hit on the head anyway.

AMMUNITION:

The player character has a limited number of bullets. He will restock in between scenarios (usually when he returns to the ship of his partner), but there are otherwise few means of restocking during the chapters in the story.

In some of these rare cases, the circumstances are understandable, e.g. pilfering the corpse of a fallen opponent. In other cases, a magazine can be found lying about or stuck in between furniture; again, this can seem unbelievably convenient.

Anyway, if the player runs out of ammunition, he is doomed. Enemies do not have ammunition limits, of course; they need an advantage to compensate for their lack of finesse.

GRAPHICAL GLITCHES IN LOADING GAME-SAVES:

The visual effects in the game are not tightly programmed; specifically, they have not been programmed to account for the loading of game-saves. Reloading a game save results in a lot of things not being rendered, or rendered as multi-coloured static. The worst cases occur in locations where there is rain; reloading one of these scenes results in almost half of the screen being obliterated.

Gemini Rue is not the first Wadjet Eye title to have rain-like visual effects. Of course, the rain in this game is much more believable than the one seen in Blackwell Convergence. However, the lack of tight programming – as admitted by Dave Gilbert on the Steam thread for this game – for Gemini Rue is disappointing.

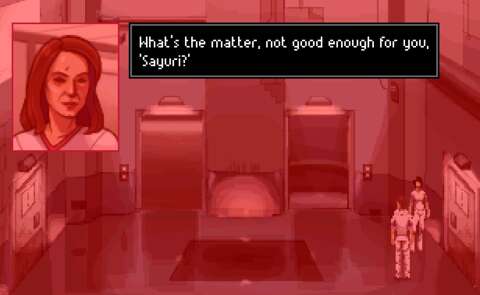

NO FACES:

Where other Wadjet Eye titles have at least tried to give faces to the sprites of characters and give them rudimentary animations, Gemini Rue does not have any. Fortunately, this is not an issue most of the time; if there are characters talking, they are the only few people in the scene and subtitles always appear over their heads. Still, the lack of faces is noticeable. Together with the aforementioned graphical glitches and cumbersome user interface, they mark the game out as not being entirely in the Wadjet Eye line-up of games.

SOUND DESIGNS:

Another thing that reinforces the impression that Gemini Rue is not entirely a Wadjet Eye title is its music; it is mostly forgettable. Incidentally, it is not composed by Thomas Regin, long-time contributor to Wadjet Eye Games. Indeed, it is so forgettable that I could not recall elements of the instruments and composition methods.

As for sound effects and ambiance, most of them are underwhelming. This is mainly due to the dismal conditions of Barracus, which seems to be rainy all the time. Indeed, the most that the player would remember about the sounds in the segments of the game that take place in Barracus is the pitter-patter of rain.

At least the segments of the game that take place in the rehab facility have sounds that are more memorable, mainly due to the oppressive atmosphere of the facility and the dilapidated conditions of their inner workings.

The voice-overs are perhaps the best of the sound designs, mainly because they have been produced under the direction of Dave Gilbert. The cast includes some voice talents that have not been in prior Wadjet Eye games, such as Brian Silliman. The others in the casting include long-time contributors, namely Abe Goldfarb and of course Dave Gilbert himself (who voices tertiary characters). With this game, Sarah Elmaleh and Shelly Shenoy also begin to make themselves known as recurring voice talents that Gilbert hires.

These voice talents deliver adequate performances, which partially compensate for the otherwise unimpressive or dissatisfying parts of the game.

A notable production decision - and not for the betterment of the game - is that Charlie's observation of things are not voiced, i.e. the player appears to only get inner monologue. In contrast, Azriel has spoken lines about his observations. The cause of this difference is at best only implied when the story is reconsidered in hindsight. It could have been a deliberate design direction, or it could have been budgeting limitation.

SUMMARY:

Gemini Rue is a milestone in Wadjet Eye’s history as a game-maker; this much is undeniable. Certain qualities of Wadjet Eye’s production shine through, such as the voice-overs.

However, the rest of the game does not exhibit the same level of production quality. The locales are few and frequently reused, with the excuses being little more than serendipity. There are significant graphical glitches when reloading games.

Years down the line, it would be difficult to recommend this game to anyone who is interested in Wadjet Eye’s works.