INTRO:

Tharsis may have been a frustratingly difficult rogue-lite, but its gameplay turns dice into something more than just the outcomes of fickle RNG rolls. It made dice into resources, something that had been done in table-top games but virtually unheard of in video games.

Perhaps deservingly, Tharsis became infamous for having incredibly fickle gameplay, much of it due to gameplay elements that are actually not the dice. Thus, its innovation would be overlooked by many other game developers, but not Terry Cavanaugh.

Terry Cavanaugh, creator of VVVVV, has diversified his portfolio by making a game that would be better at what Tharsis tried to do than Tharsis did itself.

PREMISE:

As its name suggests, Dicey Dungeons takes place in a dungeon. Initially, the dungeon looks like a film set for a game show, considering the presence of cameras, spotlights and a host that talks to an disembodied audience. The player characters are the contestants of the game show, having been somehow “invited” and brought to the dungeon.

However, it would become clear that not is all that it seems. The presumably human contestants are turned into giant dice with actual faces and comical limbs sticking out from them. The host, “Lady Luck”, eventually reveals her sinister intentions for all the contestants.

The player needs to win run after run in order to move the story forward. This might seem difficult, due to the prevalence of some factors of luck. However, familiarity with each player character’s capabilities and the intricacies of the dungeon denizens would help a lot – even if the player might find their character designs to be mostly boring.

ROGUE-LITE AND GAME-SAVES:

Dicey Dungeons is one of those “rogue-lites”, which insist that not having a versatile game-saving feature is part of the game’s “challenge”.

The player can only have one playthrough active at any time. The player’s progress in this playthrough is therefore contained in just one file. In the Windows version of the game, the game-save can be found in the usual places, such as the Users directory or the Steam data directory.

The game-save is updated in just two ways: finishing and winning a fight, or going into the gear load-out screen (called “deck” in-game) and then exiting. The latter is more within the control of the player, of course.

CHARACTER CLASSES:

For reasons that seem little more than the whimsy of Lady Luck, all of the player characters are turned into giant dice.

Despite their aesthetic silliness, the giant dice are capable of combat – somehow their transformation has also given them skills that are associated with their “character class”.

Speaking of which, the giant dice are named according to their supposed professions, each of which has been decided through the whimsy of Lady Luck.

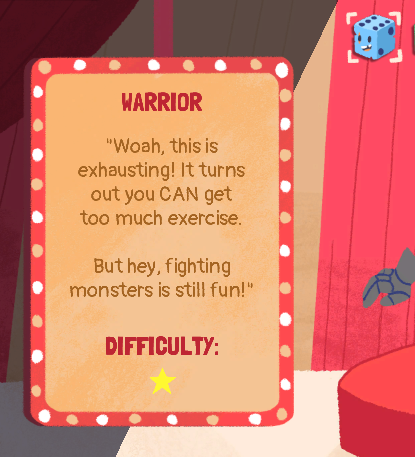

The Warrior is the first class. He has the simplest and thus most understandable gameplay. That said, runs with him often involve little more complexity than rolling dice at the start of his turn and allocating those dice into cards that represent his equipment.

The Thief is the second. His gameplay functions like the Warrior’s. However, much of his gear requires rolling low, splitting dice into more dice with lower values, or just outright generating more dice. He also gets to use the cards of enemies. This is notably more complicated.

The Robot is the third. The other giant dice get a specific amount of dice to use each turn, but the Robot does not. Instead, the player gets a mechanism that is close to the card-game of blackjack; the Robot can keep generating dice as long as the total value of the generated dice does not overshoot a specified limit.

The Inventor is the fourth. Where the Thief, the Warrior and the Robot generally keep their gear as long as the player wills it, the Inventor has the uncontrollable habit of trashing her current gear to make “gadgets”. The player has to frequently sacrifice cards in order to satisfy this habit of hers, but at least the piece of equipment that she makes can be used without any dice. Furthermore, the Inventor’s ability to turn all dice into boxcars can be devastating, if the player can find damage-oriented cards.

The Witch is the fifth. Unlike the previous four, she does not even use equipment at all. In fact, she does not always have cards prepared already. To have cards, she has to spend dice to activate her spells and put them into one of four slots, meaning that she can only have up to four cards ready for use, unlike the others that can have more. She does have the advantage of being able to refresh her cards, albeit by spending dice.

The Jester is the sixth, and is not obtained like the others. Rather, the Jester is obtained through playing the game many times and defeating a specific opponent many times. Incidentally, this unlocking process would also solidly establish a plot point, if the player has not been wise enough to realize it already.

Like the Witch, the Jester has a limited number of cards at any time – up to three, specifically. However, he replaces these cards readily, by drawing them from a deck. Indeed, the Jester is the only class that treats cards like cards. Having the luck of the draw and the roll of the dice may seem like too much luck is involved. However, the player can see what cards are going to be drawn next, and the Jester can drop some cards instead of having to spend dice on them. A crafty player can make a devastating chain of card activations, surprisingly easily.

UNLOCKING CLASSES ONE BY ONE:

The aforementioned descriptions of the character classes according to a numbered order is not without a reason. They have to be unlocked for play in that order, generally by playing one run with the previous class; the run does not need to be successful.

The unlocking of other classes might seem like a reward, or a compensation in case the player lost the previous run.

“DIFFICULTY” RATING:

However, the “difficulty” rating of the character class may disabuse the player of this notion – or not. The in-game documentation does not clearly describe what the “difficulty” rating of a character class is. Of course, more experienced players would eventually recognize it as a paraphrasing of “complexity”. However, everyone else would have been confused over what it means, especially considering that there would be gameplay elements that increase the challenge of runs.

“EPISODES”:

Every run begins with the player selecting one of the “episodes” that is associated with the character class. When playing any character for the first time, the episode that is played is always the introductory episode, in which the character is, of course, introduced.

The other episodes also have to be unlocked one by one. This is just as well, because the later episodes are more complicated, have tougher enemies or are subtly different in terms of gameplay mechanisms. These will be described later, after the mechanisms of the gameplay have been described.

EQUIPMENT AND ABILITIES REPRESENTED AS CARDS:

The equipment and abilities that the giant dice would accrue are visually represented as cards, which appear on-screen as part of the user interface during battle. Some of them might even remark that equipment like hammers appear to look like cards.

For most player characters, they can only bring a number of equipment that is specified by how the player fills a 3X2 grid of squares. Some cards only take one square, whereas others take 2 vertical squares. The arrangement of the cards does not matter, so long as they fit. (In fact, each time when the player brings up the equipment screen, the game automatically arranges the cards.)

For the Witch and the Jester, their cards number up to four and three slots, respectively. They can only allocate dice to these cards, until the cards are replaced.

A character class’s ability is virtually always available, unless they are silenced. For some characters, these are represented as cards, such as in the case of the thief, who can by default, duplicate one of the opponent’s cards for his own use.

There will be more elaboration on the mechanisms that determine the use of cards later.

DICE ROLLS AND ALLOCATION:

Whichever mechanism that is used to deploy cards, there is generally only one way for cards to be used: the player must allocate dice to them. The Inventor and Jester do get cards that do not require dice to be used, but they have subtle caveats that will be described later.

When a character’s turn comes up, he/she/it rolls the dice that he/she/it has and these are generally what he/she/it will only ever have. The exception is the Robot, which generates its dice one by one, at the player’s own discretion.

Anyway, dice that have been rolled are to be allocated to the cards; this is where Dicey Dungeons is similar to Tharsis. The player may have more dice than cards, in which case the player may be wasting dice, or the player has more cards than dice, in which case the player is spoilt for choice.

There are two overarching ways through which cards utilize the dice that have been allocated to them. Some may consume the dice and then activate immediately, if the dice is appropriate. Some others have a countdown counter, not unlike the repair counters in Tharsis.

ACTIVATING CARDS:

After a card has been allocated an appropriate die or multiple dice with the correct value, it activates. When it does, it usually disappears from the screen, unless it has been described as having multiple uses, is reusable, or has been rendered either way from an ability or another card.

Anyway, when a card is activated, its effects may be directed at the player character, at the opponent, or the player’s cards. It is not always clear which it would be.

Each card has a description that mentions what it does, but there are wordings that presume that the player knows about whom the effects would be directed at. For example, text like “lock 1 die” or “burn 2 dice” would mean that the effects would be directed at the opponent’s dice. However, there are also statements like “lose 1 HP”, which actually mean that the effects would be directed at the player character.

Terry Cavanaugh tries to address this by using colour-coding for the cards, but this is not always effective.

COLOUR-CODING OF CARDS:

Cards with red fills are mainly meant to harm the opponent. Green cards are usually healing cards, or grant some aggressive defensive bonuses, like Thorns. Brown cards are generally defensive, meant to reduce incoming damage. Yellow cards are generally meant to inflict de-buffs on the opponent. Blue cards generally apply buffs on the player character. Dark green cards alter dice.

Ultimately though, the colour-coding does not matter much, even when their functions do not overlap like in the case of green and brown cards. This is because certain cards have effects and rules that they are not so easily lumped under one category or another.

There does not appear to be any gameplay mechanism that utilizes the colour-coding of the cards. This is perhaps for the better, because some of the colour hues can be a problem to the colour-blind.

CARDS THAT REQUIRE SPECIFIC DICE:

Some cards do not require specific dice roll outcomes in order to be activated. Examples include most of the cards that are associated with the Warrior, such as the Sword. However, other cards have prerequisites.

Some cards require even-numbered or odd-numbered dice. It is possible for a character’s dice to simply all land evens or odds, meaning that these cards could not be used at all. This is observable in fights with the Snowman, Fireman or Yeti.

Some other cards require a minimum or maximum number. These cards usually involve the application of damage, though some of them use the maxima and minima as thresholds for triggering effects that are the same regardless of the dice used.

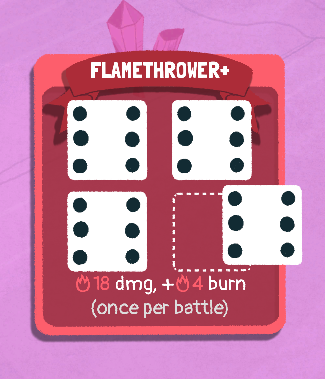

Then there are cards that require dice of exact numbers. These are rare, and their effects are often considerable enough to change the tide of the battle. For example, the Hall of Mirrors card requires a dice of 6, by default, to give the character one additional dice for the fight.

Messing up the opponents’ dice rolls is a key strategy. With clever manipulation, the player can deny the use of any of their dice during their own turns.

CARDS THAT ALTER DICE:

Some cards alter dice, so that they can be used for other cards much more effectively. Understandably, these help the player manage his/her rolled dice.

There are some dice-altering cards that “flip” dice around. Players who are not particularly familiar and experienced with real dice might wonder how the outcome would be. In actuality, these cards require the player to know about the facings of real standard D6 dice.

Some cards change the number of the dice. For example, there is the Bump card, which increases the number of the dice by 1. Some others combine dice. For example, there is a card that combines two dice; the outcome is that most of the value of the dice is concentrated in one die, whereas the other die gains the remainder.

The increments, decrements or combinations may actually result in overflows or underflows. For these cases, new dice are created in the case of overflows, or dice are taken away in the case of underflows. For example, using a 6 die on Bump increases the value to 7, so to accommodate this, the card returns the 6 die, and creates a 1 die to contain the overflow. If the player character has the ability or cards to alter dice, these freebie dice can be incredibly useful.

Some cards duplicate dice outright. These are very handy, if the player character has cards that have to be activated using specific dice roll outcomes.

CARDS WITH MULTIPLE USES:

Most cards are removed when they are activated. However, some cards can be used a few times; this is shown to the player with text labels. These cards often have limited effects, but their value often lies in their repeatability. There are also cards that are completely reusable; these often have weak effects, but are useful if the player is somehow having more dice than there are cards.

CARD UPGRADES:

Cards can be upgraded. In the case of the player’s cards, they have to be upgraded by getting them to the resident blacksmith of the dungeon. The blacksmith appears to work for free (as long as her service is not purchased through her colleague’s shop), but only one card can be upgraded at any opportunity.

Anyway, upgraded cards may have one of several discrete advantages; it is rare for them to have more than one advantage, by the way. The card may become smaller, thus allowing the player to pack in more cards into the inventory grid. The card may inflict more damage. The card may have lower initial countdowns. It may have wider dice restrictions. There are more types of improvements, often unique to the cards that are upgraded.

DICE AND CARD DE-BUFFS – FOREWORD:

In addition to inflicting damage or altering dice, there are cards and abilities that inflict de-buffs that hobble the use of cards and dice. Learning to use these would be very useful, because there are enemies that are best countered by preventing them from using their dice or cards.

Dice and card de-buffs only last for a turn. They disappear by the end of the next turn. Considering their ill effects, it might be prudent to skip a turn if the player character has many of them. On the other hand, if the opponent can reliably inflict so many de-buffs, the player is screwed.

BURN:

Dice can be set on fire. They do not destroy the dice, but they make them hazardous for their owner to use. In the case of the player’s dice, merely tapping on them (with touchscreen controls or the mouse cursor) causes the burn’s effects to trigger, which is 2 HP of damage. This damage can be nullified with shields or damage reduction (more on these later).

Burning dice will not dissuade the CPU-controlled opponent from using its dice if it has the HPs to absorb the damage. However, every bit of damage helps.

The level of the burning de-buff determines how many dice will be set on fire. If the level of the burning is greater than the number of dice, the surplus levels are not wasted; if any further dice are created as the result of the character’s decisions, these are set on fire too.

LOCK:

Dice can be locked down. This prevents their owner from ever using them; in the case of the player’s dice, the player cannot even move them. The Witch cannot even throw locked dice too.

BLIND:

Blinding causes the player’s dice to be obscured. Obscured dice remain obscured after the player alters them with dice-altering cards.

The player could still attempt to figure out what value it is by attempting to apply them to cards with dice restrictions. If the obscured dice could not be allocated to the cards, the player will have an inkling of what value the dice have.

Similarly, the player could use damage-inflicting cards that require two dice and with damage output that is dependent on the total value of the dice. If the player places obscured dice into the slots on such a card, its text description will indirectly reveal the value of the obscured dice.

Blinding is generally a de-buff that enemies use. The player can attempt to get cards that cause blindness (usually through the Thief’s abilities), but CPU-controlled enemies always know the values of their dice.

FREEZE:

Freezing causes dice to change their value to one point. This is applied on the dice with the highest value. This is effective on characters that use cards with damage output that is dependent on dice value – especially the player character.

Among the dice de-buffs, this one grants opportunities just as much as it causes hindrances. This is because the 1-point dice are still usable; there are a number of cards that can use such dice, and some others that do not require dice of higher value.

MULTIPLE DE-BUFFS ON DICE:

If a character has multiple de-buffs that affect dice, their application follows a sequence. Firstly, dice-locking is applied; any locked dice cannot be affected any further, so the other dice has to take the other de-buffs instead. Next, blinding is applied. After that, dice-freezing is applied, followed by burning de-buffs.

This sequence is not told to the player, unfortunately. This knowledge would have been helpful to players that are using card builds that are oriented around de-buff application.

SHOCK:

Shock affects cards. They prevent cards from being used. For any card that is locked, its owner has to spend one usable die (of any value) on the card to render it available. This can be costly, unless the player has spare dice to use, or has the means to generate new dice.

For every level of shock, one randomly selected card is locked. Understandably, this can unpleasant if it happens to the player. However, having more cards than one would ever use happens to be a good way to mitigate the effects of shock.

CURSE:

Curse is the most unpleasant de-buff, because it is luck-dependent. As long as a character has this d-buff, there is a 50% chance that the next card that the player is using would be outright wasted. Even if the card is reusable or have multiple uses, the card is gone. Furthermore, curse is a de-buff that generally only enemies use, which can seem unfair at times.

BUFFS AND DE-BUFFS FOR CHARACTERS – FOREWORD:

There are buffs and de-buffs that affect characters directly. These do not prevent either character from using their cards or dice, at least not in the default rules.

DAMAGE REDUCTION:

Damage reduction is a rare buff. Like its name suggests, it reduces the damage of incoming attacks. This buff is generally available only to the player. However, it only lasts for one turn, after which it has to be reset. Considering that cards that grant this buff can be tedious to use and the buff is often just one point per application, the player might want to consider the opportunity costs of activating the card.

SHIELDS:

Shields act like ablative hitpoints. Unlike the other buffs, shields can be accumulated and are not lost over the end of the turn. Any attacks that would inflict de-buffs in addition to damage will still inflict their de-buffs anyway if the shields absorbed all of the damage. However, shields will absorb any damage from handling burning dice.

FURY:

Fury is a buff that is readily available to the Warrior. Few enemies have it, and there are next to no cards that have it. Fury makes the next card to be activated activate twice in succession. This also causes any setback of the card to be incurred twice – something that can be unpleasant to learn the hard way. If used on a card with multiple uses, Fury will consume two uses instead of one. This is also not told to the player.

DODGE:

Dodge is a buff that lets a character avoid the next attack, ignoring all of its damage and secondary effects. There are two ways to work around an opponent with Dodge: focus on something else other than attacking and waiting for the buff to disappear over the turn, or spend a weak dice on a weak attack to waste the Dodge. CPU-controlled enemies are aware of any Dodge buffs and know how to do the latter work-around, by the way.

Interestingly, likely due to a programming hole, the Inventor’s gadgets can make attacks that bypass Dodge.

POISON:

Poison is a nasty de-buff that applies its effects as soon as the afflicted character gets his/her/its turn. Poison affects every character, by the way, including even the Robot and the Gargoyle.

The level of poison determines how much damage that a character would take when his/her/its turn comes up. There is no way to mitigate this damage, other than to reduce the level of poison. There are not many cards that can reduce poison levels, unfortunately. Fortunately, after every turn, the poison level reduces by one.

THORNS:

Thorns inflict damage on an attacker. Whatever the nature of the attack is does not matter; even if the attack is meant to inflict a de-buff, Thorns will trigger.

The level of Thorns determines the amount of damage that is inflicted. Only the damage reduction buff can reduce the damage that is inflicted; not even shields can do so.

THROWING UNUSED DICE:

The Witch has the special ability to toss unused dice at the enemy, inflicting one measly point of damage per die. This might seem inefficient, but there are quite a number of occasions when the player’s dice are rendered unusable, or harmful to use. In such cases, tossing them at the enemy is still better than simply having them go to waste.

Interestingly, if the dice are burning, the burning damage is immediately inflicted on the opponent. This is something that is not told to the player, but learning this through observation can be entertaining.

In the unpleasant “Bonus Round” episodes, one of the rules allows enemies to toss unused dice at the player character. This rule is generally less bad than the others, but if the player is using a card deck that is oriented around setting dice on fire, this rule can be particularly bothersome.

SPECIAL CARDS FOR SPECIFIC CLASSES:

Each character class has some cards that generally only appear in runs involving him/her. Some of these cards can be obtained through the level-up system, which will be described shortly. For example, the Sword is available to the Warrior, and rarely if not never appear in the others’.

CHARGE-UP ABILITIES:

As the player characters take damage, they gain charge for one of their special abilities. This ability is often powerful enough to turn the tide of battle, and it can also be hoarded for later fights. The wise player would consider doing just that, if only so that the next difficult fight can begin with the use of the special ability to gain an early advantage.

LEVEL-UPS AND REWARDS:

The player character can become more powerful, typically by defeating enemies. The fights do not appear to have fatal conclusions, however; presumably, Lady Luck is preventing them from dying permanently.

Anyway, accumulated experience points are somehow reset after each run. Thus, each run begins with the player fighting the weakest of enemies on the first floor, before progressing to stronger ones that yield more experience points when they are defeated.

There are a finite number of enemies in each run. Incidentally, in order to reach the highest experience level, which is level 6, the player must defeat all enemies before the last floor.

When the player character gains a level, his/her hit-points are completely restored. Indeed, this is such a significant occasion that the wise player would attempt to fight enemies in specific orders. For example, it would be wise to pick fights that minimizes HP losses prior to fighting a tough enemy that would inflict a lot of damage but otherwise give enough XP for a level. Learning how to do so will be essential for successful runs.

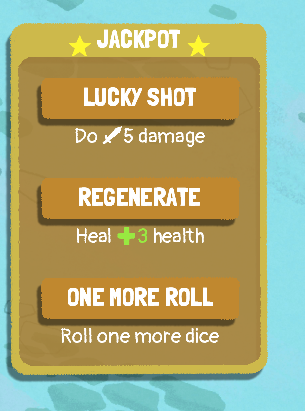

A level gain also yields other things, depending on the character class. The even-numbered character levels usually grant additional dice, whereas the odd-numbered ones grant cards that are specific to the character class. Some of these cards are potent, even important. For example, the Robot gets the Buster Sword, which is one of few cards that are immune to errors caused through its dice generator.

ENEMY’S CARDS AND DICE:

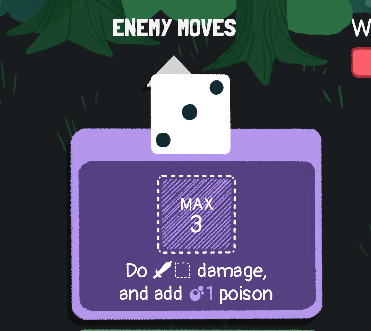

Enemies also have their own cards and dice. Knowing this information is important when deciding which enemy to fight next. (Knowing this is also important for the finale, which will be described later.)

The number of dice that they get are often decided by their card designs too. For example, enemies with cards that can only be triggered with even-numbered dice often have a considerable number of dice, if only so that they can roll some evens.

The dice and cards that they get are used to categorize them according to character levels too. For example, the enemies with the least dice and/or cards appear on Floors 1 and 2 as level 1 or 2 enemies. The later ones have more dice and cards, so they have more options during combat.

SLIGHT LEVEL VARIATION IN ENEMIES:

Some enemies occupy more than one level of categorization. For example, Slimes can be level 1 or level 2. If they are level 2, they have one more card and one more dice; this makes Slimes much more difficult to deal with. (Indeed, Slimes are one of the most daunting enemies in the game, due to how much poison that they can stack.)

SUPER ENEMIES:

After the player has “won” at least one run, enemies that have been rendered “super” will begin to appear. These enemies have more hitpoints than their regular versions, more dice, and more cards. However, their level remains the same, and they still give the same amount of rewards. Obviously, fighting them would not be fun.

UPGRADED ENEMY CARDS:

The player would eventually unlock the episodes where enemies have upgraded cards. Upgraded enemy cards are often more powerful and/or easier for enemies to use. For example, the Wizard has the upgraded Hall of Mirrors cards, which let him gain more dice through allocation of even-numbered dice to the cards instead of exact 6’s. Understandably, runs with these episodes are more difficult.

THIEF’S BORROWING:

The Thief has two special abilities instead of just one. One is a rather underwhelming but subtly useful ability to generate four dice with values of 1 each. (Certain episodes replace this ability with something else, but generating low-value dice is still its function.)

The Thief’s other ability is to generate an additional card from the enemy’s deck. This will not prevent the enemy from using the card, but there might be some appeal from harming the enemy with its own card.

However, for some enemies, it might not be wise to use the card against the enemy, especially the Snowman and Yeti. Using their own cards against them means that they are afflicted with Freeze, which turns their dice into 1’s. Of course, 1 is an odd number, and their cards so happen to be triggered with odd-numbered cards.

ROBOT’S DICE GENERATOR:

The Robot does not have any dice, but gets to generate as many as it could as long as it did not exceed certain limitations.

As mentioned earlier, his dice generator works like blackjack. At first, it might seem that the Robot has a more complex system of resource management.

The player can keep generating dice as long as the total cumulative value of the dice that have been generated does not exceed the “target”. The total cumulative sum also includes the values of any dice that have been allocated.

Yet, the most problematic setback of this system is that if the player overshoots the target, virtually all unused cards are removed from the screen. Only cards that are immune to this “error” will stay.

After several runs of having to use “error”-resistant cards to absorb any dice that caused the overshoots, the Robot’s playstyle can eventually seem stifling. It would have been more fun if unused cards did not disappear upon overshoots.

INVENTOR’S LIMITED IMAGINATION:

As mentioned earlier, the inventor has a habit of trashing her cards to make “gadgets”. Gadgets can be used without any dice, so this might seem to be a good thing, as long as the player can manage the frequent replacement of her gadgets.

The problem is her limited imagination, or to be precise, the limited variety of gadgets that she can make. Different cards might be turned into the same gadget. For example, any card that inflicts fire damage would be turned into a gadget that inflicts some fire damage, regardless of how that card actually works or how much damage that it does. This limitation also extends to upgraded variants of cards.

WITCH’S PREPARED AND BOOSTED SLOTS:

The Witch is exempted from any card upgrading system, because her gameplay system makes use of slots that already take into account the regular or upgraded versions of her cards.

When the Witch gains even-numbered levels, the player is presented with two mutually exclusive options. One has one of her slots already prepared with a spell, so she does need to spend any dice to activate her spells.

The other option turn one of her slots into a “boosted” one. Any card that is placed into a boosted slot becomes an upgraded card. This can take up quite a lot of dice, which diminishes the Witch’s damage output.

Wise players would likely opt for the prepared slots, if only to minimize the vagaries of luck and so that the Witch can do something in the first turn instead of prepping spells.

WITCH’S NUMBER-CODING FOR SPELLS:

Another layer of complexity with the Witch’s gameplay is that her spells are number-coded according to the values of the D6 dice. That means that she can have up to six spells, but the player must carefully allocate each spell to any of the numbers. For example, the player might want to avoid assigning Hall of Mirrors to number 6, or any even number for that matter, because the card itself needs dice with these values to be activated.

The number coding is used to determine what spell that she can use to fill in a slot, or replace a spell with. This allows the player to use the same spell more than once in the Witch’s turn, if the player has enough dice. Replacing spells is also a good way to work around any de-buff that affects cards, especially the alternate version of poison.

JESTER’S DECK:

The Jester is the only character with no limit to the cards that he can have; even the Witch can only have up to six spells.

However, the player has to manage the risk of having the cards being all mixed up at the start of every turn. The order in which the cards appear might not be convenient, and having to have the correct dice to use on them can lead to more complication than the player would like.

The deck can be altered by removing cards from the them too; this can be done at the vendor (more on this later). However, the opportunity to do this is limited and it does require coins.

FLOORS:

Lady Luck’s dungeon is organized in floors. The floors are reorganized for every playthrough, hence this rogue-lite ticks the checkbox on “procedurally generated levels”.

Each floor has a layout that is built on a sequence of nodes. The player character begins on one node, and has to travel to the node with the exit to the next floor. Of course, this is easier said than done, because there are enemies in the way.

Speaking of enemies in the way, the player character cannot move to any other node as long as all possible paths to the node contain enemies. The player character will automatically take the long way around an enemy if it is possible; there is no cost to doing so.

WASTED OPPORTUNITY ON BIOMES:

The floors have aesthetic themes, such as being a clearing in the middle of a jungle, the floor space of a library or the dank depths of a gaol. These serve no gameplay purposes, however. There could have been additional procedural generation scripts that are oriented around introducing enemies according to biomes, but there is not any. There is also not any gameplay mechanism that is oriented around biomes.

COINS:

“Coins” are the currency that is used in the dungeon. That there is somehow a currency in what is supposed to be some kind of game show parody is not really explained in the narrative.

Anyway, coins are only ever obtained from defeating enemies; presumably, they are forced to yield their coins, though where they got them is unclear. (Lady Luck is implied to have never paid her minions.) They are never found as loot, which can seem odd.

CHESTS:

Dungeons would not be complete without chests filled with loot. Enemies often bar the way to these, but otherwise there are no other obstacles like them being locked. There is the infamous Mimic, of course, though it would not take long for an observant (and perhaps quite cross) player to notice the presence of a mimic without having to hover the cursor over any chest.

APPLES:

Through the dungeons, there are somehow large fresh apples that are lying about waiting to be eaten. As to be expected of video game food, they restore the health of anyone who eats them. Incidentally, only the player characters can eat them, despite being giant dice and that there are other people in the dungeons that can eat the apples.

Gameplay-wise, the player has to manage the consumption of the apples carefully, especially before fights that would not grant enough experience points to achieve a level-up. Thankfully, the player character does not immediately eat any apples that he/she comes across. Rather, to eat an apple, the player needs to click on the node that contains the apple.

Like the chests, there is a monster that mimics apples. This can be unpleasant, because the distribution of applies is freer than the distribution of chests, so fake apples are more difficult to spot.

VENDORS:

Throughout the dungeon floors, the player would come across a trio of horned teal-skinned ladies. They are the only denizens who are not outright hostile, and they offer some services that can help the player improve his/her load-out.

The shopkeeper is the only person in the dungeon that acknowledge the coins as currency. Wherever she sets up shop, she offers three purchasable options; the options may be a card, an upgrade or an apple with 10 HPs. In the case of the upgrade, the player must decide on it immediately after the purchase.

The dealer is a rare vendor; her stall is shaded in hues of green instead of brown. The dealer offers only one deal: the player exchanges one of his/her cards for another. The deal is rarely good, unfortunately; the card that the dealer wants is often the card that the player has been using frequently. The other card does not always have commensurate value, and may even have a completely different function.

As mentioned earlier, the blacksmith would apply an upgrade for free, if she is found elsewhere other than at the shop of her colleague. She appears in most runs, except those for the Witch, because the Witch’s card-upgrade system has been repackaged as her boosted slots.

CHARACTER-SPECIFIC EPISODES:

Three of the episodes for each character specifically involve the gameplay designs of the character; these episodes have their own unique names. Their gameplay differences are relatively easy-to-understand and they can still provide considerable challenge. For example, there is an episode that causes the Warrior to lose health as he gains levels.

The other three episodes are far more complicated than the first three. Incidentally, the player needs to have played the earlier three to unlock these.

PARALLEL UNIVERSES - FOREWORD:

There are episodes called “parallel universes”. These make for some of the toughest runs in the game. This is because these episodes are the depository for some of Terry Cavanaugh’s worst ideas for the gameplay designs. These very different designs can make for wildly inconsistent experiences from runs with these episodes.

COMPLETELY DIFFERENT STATUS EFFECTS:

Firstly, there are completely different effects for de-buffs and buffs. Fortunately, the game does change the tool-tip text for them so that they are easier to understand.

For example, there is the different mechanism for shields. Shields will heal the character in the next turn by an amount equal to their level. For another example, “damage reduction” is replaced with an ablative shield that protects the character from enemy-applied de-buffs.

Perhaps the problem with these different status effects is that their descriptions are only viewable after they have been applied. They could have been easier to learn if the cards that apply them also included these descriptions.

DIFFERENT CLASS ABILITIES:

Most of the classes have their abilities changed too. For example, the Thief gains a counter-based card that when activated, allows the player to pick one of the enemy’s cards to keep. This is an incredibly useful ability because some enemy cards are rather powerful.

Wrapping one’s head around the different mechanisms in Parallel Universe runs can be a bit daunting at first. However, they are often a lot more exploitable in entertaining ways – which is perhaps why they are relegated to these episodes in the first place.

ELIMINATION ROUNDS:

The elimination rounds bump up the hitpoints of enemies and upgrade all of their cards. Obviously, these differences make for stiffer challenges. Incidentally, when the player unlocks the elimination round for each character, starting a run with it shows a cutscene that has the character making statements that they are well aware that the game show is rigged.

BONUS ROUNDS:

Bonus Rounds are the final episodes for all characters. All enemies receive a bump to their hitpoints, by default.

Unique to the Bonus Rounds, the player is given the choice of selecting the starting cards for the player character. The packages of starting cards also changes from run to run. There are not a lot of choices though, since the range of cards that the packages draw from is limited.

Speaking of cards, the player will be finding cards from both the runs with regular rules and the runs with Elimination Round episodes. Mixing and matching them will be needed to overcome the enemies in the Bonus Rounds.

The main gimmick of the Bonus Rounds is the implementation of rules that can greatly shake up the gameplay – usually not in the favour of the player. Each floor after the first one requires the player to pick one rule to implement.

One of the choices is already revealed to the player. If the player does not like that rule, the player can attempt to pick another, but this one is ‘randomly’ picked from the others.

The truth is that the one that would be selected through the so-called “random” option is actually already pre-determined through a seeded variable that has been made for the playthrough. Even if the player tries to save-scum, or even restore an earlier game-save to replay entire floors, the two options at the end of any floor will always be the same. This can result in terrible choices, like giving enemies more hitpoints or giving them a free Dodge in every round.

BONUS ROUND RULES:

The Bonus Round rules are mostly troublesome. One of them causes dice – especially the player’s dice – to simply disappear if multiples are rolled. Not being able to use dice is a major setback.

For another example of a rule that makes things more difficult, there is one that increases the health of enemies by 20%. This is stacked on top of the 10% that the Bonus Rounds already apply.

Not all rules are awful though. There are some rare ones that might seem beneficial, or at least double-edged. For example, there is a rule that causes the Curse de-buff to have a 25% chance of occurring instead of 50%. Since Curse is mostly inflicted on the player, this is a good change.

There are also some rules that are definitely double-edged. For example, there is a rule that causes any dice with values of 6 to be automatically set on fire.

BROKEN BONUS ROUND RULES:

Unfortunately, the Bonus Round rules also reveal how poorly the game is designed for intermittent gameplay.

For one, there is the rule that hits the player character with a health penalty. If the player leaves during the game during a Bonus Round run with this rule, the player will be hit with the death penalty again. Repeated save-scumming will stack this penalty indefinitely, until the player character’s health goes into the negatives by default. The next fight will immediately lead to a game-over.

For another example, the rule of enemies always rolling 6’s does not appear to work at all.

CHALLENGES:

Shortly after the player has finished a run successfully, the player is shown the list of “challenges”. These are the game’s “achievements”, albeit implemented in-game too. The player’s rewards are short biographies of the enemies that the player would encounter.

Dicey Dungeons is hardly the first game to do so. Furthermore, the writing in these biographies can range from decently amusing to just groan-worthy to a jaded follower of fiction-writing.

ENEMIES ARE PEOPLE TOO:

It is not uncommon for indie games to give personalities to individual enemies, especially if they are recurring characters. Dicey Dungeons is a particularly notable example. In its case, it has actually done more than just the mediocre writing in the “Challenges” feature.

Observant players might notice that a specific type of enemy never appears more than once in the same floor. He/She/It may appear in other floors, but never twice in the same floor. This is because the denizens of the dungeons are indeed individuals.

Indeed, as the player encounters them in fights and defeats them, they would make remarks about their histories or preferences – or incomprehensible gibberish, in the case of clearly inhuman creatures like the Slime and Crystallina. It is as if they are growing friendlier from each pounding that they took.

Of course, this might not seem like much to a player that is more concerned about gameplay than story-telling. However, in the run-up to the finale of the game, there is one last gameplay element that the game would reveal – and it is very, very entertaining.

REBELLION:

The following is understandably a spoiler, but it also happens to be about gameplay mechanisms that were not present in the earlier segments of the playthrough. In fact, they are going to replace most of the earlier gameplay mechanisms.

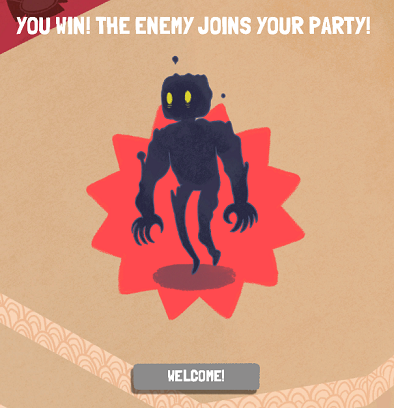

The final chapter has one of the giant dice leading a breakout attempt. Any enemy that the player character comes across and defeats joins his/her party. These former enemies retain most of the cards that the player should have learned that they have. However, they have substantially reduced HP – likely for purposes of gameplay balance.

The vendors no longer offer any services, but if they are found, they give dice, which is helpful. Of course, enemies bar the way to them. As for the apples, they give 10 HP each and the player gets to decide who eats them. (So the minions do eat the apples too!)

MAIN PLAYER CHARACTER ABILITIES DISABLED:

The most significant setback of the final chapter is that the abilities of the giant dice are all disabled. They get a fixed set of cards; they are a bit more than their usual starting sets, but that is it. The fixed set of cards completely nullifies the Inventor’s gadget-making habits, and the Witch cannot prepare or change spells.

Many of their gimmicks are also disabled, and sometimes not for the better. For one, the display of the Jester’s upcoming cards is obscured by the button to switch characters. Thus, it is more difficult for the player to plan for his upcoming cards.

The ability that charges as the player character takes damage has been replaced with one that generates even-numbered dice. This might not be helpful if the player has recruited individuals with cards that require odd-numbered dice.

SWITCHING PLAYER CHARACTERS:

During combat, the player starts with the main player character. The player can switch to any of the minions, and from there, back to the main player character or other minions. This can only be done once, so whoever that is switched to will face the ire of the opponent. This is important to keep in mind, especially when fighting against the final boss.

Furthermore, the player is likely to have more dice than there are cards for any player character. Some characters, like the Handyman, do have reusable cards, but the player is better off switching characters so that the dice can be spent as efficiently as possible.

CHARACTERS BEING KNOCKED OUT:

Any characters that are knocked out are out permanently. In the case of the main player character, having him/her knocked out ends the run immediately, so the player might want to have the others take hits if possible.

The player can have at most 11 characters, and most of them do not have a lot of HP. This is important to keep in mind, because the final boss has attacks that can potentially one-shot most characters.

FINAL BOSS’S GIMMICKS:

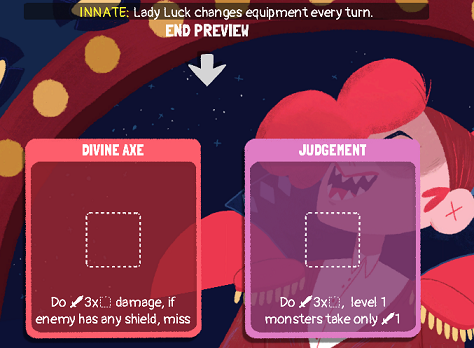

The final boss always rolls boxcars. Many of her cards would also be incredibly powerful, but with weird setbacks. Her cards also change frequently, thus requiring the player to check the cards that she would be fielding – not unlike what the player would have been done when fighting the Jester prior to him becoming a giant dice.

The final boss will also make new rules on the spot, usually a prohibition of sorts. This does not prevent the player from doing what is prohibited, but doing so immediately causes a backlash, such as loss of health or infliction of de-buffs.

VISUAL DESIGNS:

The game does noticeably look different from Terry Cavanaugh’s earlier works, especially VVVVV. Dicey Dungeons is made with Flash and Unity, so there are layers of animated 2D artwork.

The player should not expect anything that is more sophisticated than idle animations, however. Indeed, most characters retain the same posture throughout the game. In fact, Lady Luck is the character with the most expressions and poses, far more than the other characters.

The “3” facing of the standard cubic dice happens to be where the “faces” of the anthropomorphic dice are located. The various numbered faces of standard D6 dice are also represented on their persons. This is something that might be helpful if the player is using cards that flip dice instead of re-rolling them.

There are two sets of sprites for each character: one set is shown during battle, whereas the other set is used for their visual representation on the dungeon floor. The latter is noticeably super-deformed, more comical and has only two frames. Perhaps they are intended to be an homage to old JRPGs, when sprites that are in the view modes for strategic planning did not (and still not) have many animations.

The most energetic animations that the player would see are the activation and movement of cards. This can seem underwhelming, especially if the player has played indie games with far more animations. (Terry Cavanaugh may have the excuse of working alone, but there have been other lone developers that did far better in the graphics department, like the developer for Dust: An Elysian Tail.)

SOUND DESIGNS:

The first thing that the player hears from the game is the music, which is just as well. The music is composed by Chipzel, who is skilled at “9-bit” tracks. With this game’s tracks, Chipzel has expanded its portfolio to include digital versions of instruments that are associated with jazz, especially the saxophone.

Most of the tracks are short and designed to loop. These are used for the menu screens, when the player is in the dungeon floor screen, or any other situation outside of battle. The longest tracks are used for fights, and these can stretch into minutes. They are great to listen to though, and help compensate for the otherwise lacklustre presentation of the combat in this game.

There are not a lot of legible voice-overs. Most characters make illegible utterances, like groans, grunts, yelps, pause fillers (e.g. “hmmm”) or animal noises. Only the Witch has enunciated voice-clips, and even then most of them are Harry Potter-inspired gibberish.

When the characters “talk”, the player would hear the kind of beeps and boops that one typically hears when characters talk in JRPGs. In the case of Lady Luck, she will make some illegible utterances too, but there is little else.

The activation of cards is accompanied with sound effects that are mostly appropriate with what the cards would do. For example, if the player activates the Sword card, the player can hear the clash of something solid on something else.

SUMMARY:

In terms of gameplay designs, Dicey Dungeons did well what the infamous Tharsis has failed to do, namely utilizing and highlighting the innovation of using rolled dice as resources. Furthermore, Terry Cavanaugh has gone a step further by giving each individual player character his/her own unique gameplay. Indeed, most of the appeal of the game lies in the variety of the gameplay mechanisms for the player characters.

However, there are a few lost opportunities to introduce more complexity to the gameplay. There may have been plans for biomes, but the different environments are little more than aesthetics.

That said, Dicey Dungeon’s presentation leaves something to be desired. There have been indie games with better 2D animations and/or artwork. Its attempts at humour is not always effective. Chipzel’s music goes a long way, but disabling the music would reveal how bland the game could be without its strongest aesthetic element.

There are some teething problems, such as bugs that remained at this time of writing, several months after the release of the game. The major changes in the main player characters' capabilities in the final chapter also waters down the differences between them.

Still, Dicey Dungeons is by far the best video game at implementing a complex system involving dice, thus making factors of luck a lot less prominent in the gameplay.