INTRO:

Post-apocalyptic stories were quite popular in video games for a while. The demise of civilization and having to rebuild everything from scratch made for both storytelling fodder and a convenient excuse for extensive progression systems.

At the time of Shardlight, some of the appeal has waned; there had been plenty of such games with these settings. Some of them were even high-profile disappointments, namely the most recent Fallout titles. Thus, Shardlight came out during a time when there is questionable demand for games with such themes.

Still, Shardlight is the personal project of affiliates-turn-employees at Wadjet Eye; if anything, it is noteworthy for Wadjet Eye’s leadership – namely Dave Gilbert – being willing to put resources into developing something that employees came up with.

PREMISE:

As mentioned already, Shardlight takes place in a post-apocalyptic world. Some time after the turn of the century, wars for scarce resources erupted, and – of course – said resources were destroyed together with the world that was. What is left is barely able to support the survivors and the next generation.

The events in the game take place in the ruins of some non-descript Western English-speaking country, specifically in one of that hemisphere’s ruined cities. Although it has only been a few decades, society in that city has changed into a dystopia with a clear class divide, with the poor having little to no resources; scavenging is a major economic activity.

The supposedly wealthy of course get the lion’s share of the still-dwindling resources. Furthermore, above everyone else, there are the “Aristocracy”. They are practically despots who make decisions for everyone, whether they like it or not. Backing the Aristocracy is soldiery with Imperial-era get-up and breach-loaded rifles with bayonets; as silly as they look, these are stone-cold killers.

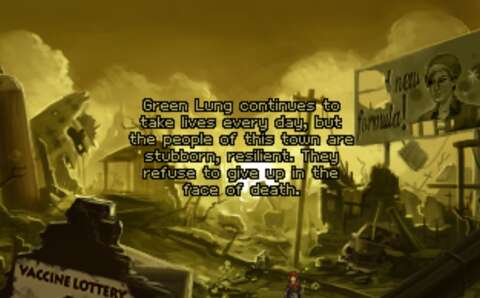

This dystopia would have been bad enough – and quite typical in post-apocalyptic stories. However, there is an additional plot element: a plague. Specifically, the Green Lung is a plague that has been around for a while, likely a consequence of the aforementioned wars. There is a vaccine that can stave off its worst effects, but it is temporary. Of course, frequent supplies are the privilege of the wealthy; everyone else has to work dangerous jobs to even have a chance at getting any. These jobs are called “lottery jobs”.

It is through one of these lottery jobs that the player is introduced to the protagonist, Amy Wellard. She is a part-time scavenger, her main vocation being that of a mechanic. She has Green Lung, and intends to somehow gain some vaccine through the lottery jobs.

She stumbles across the previous person that is sent to do the lottery job; that person had an accident, and is dying. Before he died, he assisted Amy, and in return, asked her to fulfil a task. This task will get her into ordeals that will determine the fate of the city.

Of course, that is just the prologue: the world-building happens after that. Such a set-up is very much a characteristic of Wadjet Eye titles – something that creators Ben Chandler and Francisco Gonzalez have learned from their time working with and under Dave Gilbert.

NOT FOR PLAYERS WHO WANT CLEAR GOALS:

Unfortunately, although they may have learned lessons about story-telling and –pacing, they have not learned every lesson about gameplay designs. The following are passages about certain design gaps.

Early on in the game, Amy intends to find someone to deliver something to. The player would eventually hit a dead-end of sorts. That is because that someone is not someone that is easily found and who also does not want to be found, at least not by people that this person could not trust.

The player’s only clues on how to make progress are characters that make circuitous remarks; one of them mentions “reading between the lines”, to cite an example. Then, for some reason that is only clear in hindsight later, one of these characters simply drop a hint about what to do next. Again, what has to be done is only clear in hindsight.

These clues might not be new to players that have played adventure games with far more vague puzzles. In particular, these clues might not deter players who have simply learned to just look for something to do, regardless of story-telling context, i.e. players who just progress by stumbling into everything and doing whatever that can be done at the time.

Most importantly, Amy has to have met a certain character in order for the observant player to connect the dots between the clues and hints. However, this character happens to be quite out of the way; only players who wander about trying to get anywhere that can be reached would come across him.

For other players though, especially those who want the puzzles designed with the narrative in mind, such a puzzle design might seem like an unnecessary head-scratcher that gets in the way of the storytelling.

SHORT STINT PUZZLES:

Of course, previous Wadjet Eye titles and plenty other adventure games besides have had puzzles that can only be solved by doing whatever that can be done at the time. However, the circumstances for these puzzles are much more convincing, e.g. the protagonist is trapped or imprisoned in some small space, or is in a precarious situation with few things in reach. There are such moments in Shardlight too.

Puzzles that can only be solved by doing whatever that can be done at the time are much more satisfactory when the player’s options are clearly limited. The aforementioned obstacle about finding a certain person in the city does not have such narrowly defined circumstances.

PHYSICAL PUZZLES WITH SUBTLE HINTS:

There are some puzzles that would require the player to recall some lessons on physics. For most of these puzzles, a character might make a remark that gives a clue on what to do; incidentally, Amy, with her technical knowledge, should be the one that would make this remark, and she does so in some cases.

However, this does not always happen when it should. There are some design gaps, such as a puzzle that requires the player to open a window that happens to be dampening the sound of an indoors bell. Amy can ring the bell without opening the window first, but her remark about this not doing much is not accompanied by any clue. Thus, it is up to the player to recall technical knowledge about walls and windows dampening sounds – something that most players are not likely to be able to do, at least not immediately.

NO IN-GAME RECORD-KEEPING:

Prior Wadjet Eye titles like the Blackwell games and Primordia provide the player with a list of clues that the protagonist has learned. This can be problematic to players who do not take notes. (Incidentally, Dave Gilbert himself has mentioned that taking a break from the game to write notes about obstacles and puzzles would break the player’s immersion.)

This is a frequent concern throughout the game. Amy must meet certain people and ask them for help, because they have the skills that she needs but she does not have. She is informed about other people having these skills earlier, but it is often up to the player to recall this information because Amy will not have monologues about remembering who can do what.

Of course, this would not be an issue if the player is playing on a long stretch. For other players who have other things on their mind and could only play for short stretches, this will be a problem.

FEATS WITH ADVENTURE GAME STUDIOS:

Co-creator Ben Chandler coded most of the custom-made modules that are used for the game’s more intricate puzzles. For example, there is a puzzle about connecting threads together to reveal a hidden message; the player uses the mouse to control the threading.

These puzzles are not easy to implement, because Adventure Game Studios – which is used for almost every Wadjet Eye game – is an aging clunker.

On the other hand, the programmers may have gotten carried away with coding the custom-made modules; some of them never made it into the final version of the game. For example, there is a puzzle about using a cleaning agent to reveal a clue; this puzzle was removed. This would not have been a problem, except that the cleaning agent remained in the game as a red herring.

RUN-OF-THE-MILL GAMEPLAY:

Otherwise, Shardlight has rather run-of-the-mill gameplay; for one, the player would be using items on other things after the player has figured out which thing to use on what. Other Wadjet Eye titles have more challenges, such as bringing up the right topics to the right person like what was done in Resonance.

VISUAL DESIGNS:

One of the two creators of the game happens to be a prolific artist, having worked on previous Wadjet Eye titles. His ability very much comes to the fore in this game, though not in a manner that would be convincingly impressive to everyone.

The visual motifs of Shardlight remain consistent almost throughout the entire game. There is demure lighting, with a lot of beige and grey that depict the devastation that has been around since the bombs fell. There is also the proliferation of the material known as “uranium glass”, in the form of shards that can catch the sunlight and somehow re-emit a glow of its own (which is of course the titular “Shardlight”). Consequently, most of the game has a melancholic – and perhaps depressing – impression.

Only one segment of the game is visually different from the rest of it, and very notably so. This segment has a lot of disease-ridden corpses lying about. They are disintegrating from post-mortem Green Lung infestation, if they are not being piled up and burned. If the corpses are not lying about or are not burning, they are hanging from their necks. This particular chapter of the story is very grim – perhaps amusingly so for players who are jaded.

CHARACTER PORTRAITS:

Portraits for characters with multiple expressions since The Blackwell Epiphany; they are much better at expressing the characters’ emotions than their pixelated sprites ever would. Thus, it is fortunate that Shardlight has this design direction too.

The portrait with the most variations is of course Amy’s. The most amusing expression is that of shock, which she expresses more than once in the story; as hard as her life is, she had not seen much brutality and grimness yet.

ANIMATIONS:

During the Sierra and LucasArts years, there were some adventure games that were particularly infamous for having gory pixelated scenes. There are a number of these scenes in Shardlight, which would make this game one of the bloodiest prior to Unavowed (which has much nastier scenes).

Other than these, the animations are the kind that is to be expected from games styled around those from the Sierra and LucasArts years, e.g. characters having their arms at 90-degree angles when they hand things to other people.

SOUND DESIGNS:

Like other Wadjet Eye titles, the voice-overs are the best sound designs in Shardlight. Shelly Shenoy, who was the casting director for previous Wadjet Eye titles, gets the main role this time as Amy Wellard. Amy can sound rather subdued at times, even in ugly scenes; on the other hand, this does fit her personality as someone that has experienced a lot of loss.

As a protagonist of a Wadjet Eye game, Amy is notable for not having any companion by her side for most of the game. Therefore, most of her monologue (which is apparently spoken out loud) is heard by no one else. This is, of course, a trope of adventure games.

The main antagonist is voiced by Abe Goldfarb, long-time main-stay of Wadjet Eye. As the voice of the villain, Goldfarb went a long way to enrich a character that otherwise has no facial expressions due to the use of a porcelain mask.

The ancillary characters are similarly voiced by those that have worked with Wadjet Eye for a long time. Daryl Lathon’s presence in the game is made known early, as are frequent contributors like Brian Silliman. As always, their performance is appropriate for the characters that they voice, though the absence of bloopers in the developer commentary is notable.

Nathaniel Chambers, who has composed music for previous Wadjet Eye games such as Primordia, is the composer for this one. Most of the music is instrumental guitar, which is performed by Frank Gonzalez’s presumably familial acquaintance. There are digital facsimiles in the composition too, of course; as the guitarist would mention in one of the commentaries, the notes are too complicated for a human with two arms to execute at any speed other than slow. As for the theme of the music, much of it is demure and melancholic; of course, this fits the post-apocalyptic setting.

In the matter of sound effects, the post-apocalyptic setting would not offer much; breezes blowing dust and crumbling cement are the most audible ambience in most scenes.

SUMMARY:

Indubitably, a long-time game developer would eventually make a run-of-the-mill product that is noteworthy for just being decent at best. Shardlight is Wadjet Eye’s example of this.

However, it lacks the quality-of-life designs that other Wadjet Eye games have, such as the protagonist taking notes about what needs to be done. This is in contrast to other contemporary Wadjet Eye titles, like Primordia and – especially – the Blackwell games.

Nonetheless, Shardlight still delivers on what Wadjet Eye titles do best: (mostly) satisfying story-telling, interesting presentation and tight writing.