INTRO:

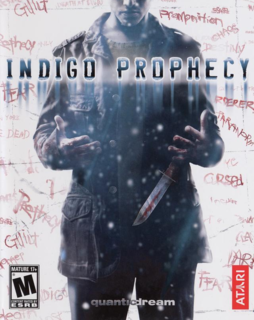

Themes and settings such as conspiracy theories, zero-to-hero, latent superpowers and murky pasts have become quite the trope in works of fiction. However, it did not stop the likes of Quantic Dream to mash all these together for their next game after Omikron. The result is an adventure game that is quite far removed from the usual point-and-click fare, though it would not seem positively refreshing to everyone – especially to those who despise Quick-Time Events (QTEs).

PREMISE:

The introductory chapter is perhaps the most gripping segment of the story. Murders are yet again occurring across one of the USA's cities; the only interesting difference this time around is that the perpetrators do not appear to remember a single detail of their heinous acts. Amidst this, the world appears to be undergoing an unprecedentedly rapid climate change.

(Incidentally, one of the titles of the game reflects this latter occurrence, but the game was renamed in the USA to avoid confusion regarding a certain documentary that mocks politics in the USA at the time.)

The player takes on the roles of a few characters that are caught up in the occurrences in this game, though one of them is particularly pivotal to the story. The player's decisions will decide the fates of these characters; they can die if the player did not manage them well, and this may well lead to a game-over. If the player perseveres, he/she can watch the story unfold and turn into something that is far from dull but which may seem outrageous as well.

CONSEQUENCES OF DECISIONS:

An aspect of the game that the game will drill into the player early on is the consequences of the player's decisions. The protagonist starts out in a very compromising position, specifically one that would get him into hot water if he doesn't clean/cover up what he had just done and quickly so. The player has to take decisions that calm him down as well as buy him time, if only he could just escape without leaving too much of a trail.

Indeed, if the player decides to have him fumbling out, this decision will have consequences down the line – specifically consequences that could lead to a game-over much more easily, with far less room for error than if the player had handled the prologue chapter in a wiser manner.

Unfortunately, this is the furthest extent of the game's designs for long-term consequences would get. Eventually, the story will heat up, and short-term consequences become the norm instead of the exception. The long-term development of the story, namely its overarching plot and how it turns out, is ultimately out of the player's control.

(It is worth noting here that Quantic Dream would later learn from this limitation in order to ensure that its next game has less of this drawback.)

That is not to say the short-term consequences are all as shallow as a trip to the several game-over screens in the game. Some of these are the results of the game's conversation consequences, which have the current characters in play (usually) sitting down with someone else to talk. The player is presented with some dialogue options, which may yield more information about the happenings in the game or provide boosts to the player characters' mental health (more on this shortly).

However, it is more likely that the player would remember these conversation sequences more for the quality of the voice-acting in this game than their gameplay or story consequences. If there is any memorable conversation consequence, it is one that involves helping one of the player characters achieve his current goal, but at the expense of another player character, which is a refreshingly interesting scenario.

MENTAL HEALTH:

One aspect of the game that was quite hyped up is the "mental health" of the character that the player is currently controlling. This mechanism is actually the representation of the game's short-term consequences and also acts as a sort of "life meter".

Every character that the player controls is ultimately a mortal, specifically one that is not used to extraordinary circumstances. This is emphasized in the prologue, where the aforementioned protagonist gets into trouble that puts him in a lot of distress. His mental health is displayed via a meter of arbitrary measurements; the emptier the meter gets, the worse his (vaguely defined) mental state is.

If this meter goes empty, the character that is under the player's (not-guaranteed) control simply outright fails to get out of his/her current situation, dooming the player to a game-over. The outcomes of an absolutely emptied-out mental health meter are not unique, as bad decisions on the part of the player can lead to the same outcomes, regardless of the characters' mental health.

The character's mental health can be refilled by having him/her perform actions with results that are to his/her liking. These actions appear to only preserve his/her mental health, and do not appear to have any long-term consequences.

At best, this mental health mechanism somewhat has the game divulging from the usual gameplay of adventure games by providing a constant source of worry for the player, who otherwise only has to focus on the current situation.

However, in the last few chapters of the game, this mechanism is thrown out the window, as it happens to be no longer important when the story has increased in outrageousness such that mortal concerns such as mental health seem petty in comparison. In fact, when the visual indicator for mental health changes does appear in these latter parts of the game, it may even seem silly and inconsequential.

QUICK-TIME EVENTS & EXTRA LIVES:

Unfortunately, instead of realizing how refreshingly sophisticated that the mechanism of consequences of decisions is and building on it, Quantic Dream decided to implement more and more QTEs as the story gains more supernatural and outrageous elements.

At first, most of these QTEs appear for optional decisions that the player can make, namely those that improve the mental health of the characters but generally do nothing else. Actions such as taking cups to a coffee machine and playing a guitar have QTEs, which the player must complete successfully; failing these cause the character to flub, which in turn cause them to lose mental health instead.

Eventually, when characters with superhuman powers start to become prevalent, a lot more QTEs occur, and many of these have to be successfully completed in order to progress in the story.

Players who prefer more traditional gameplay in adventure games are likely not to be enamoured by such moments. Unfortunately, the QTEs are part of Quantic Dream's vision of this game being more of an "interactive film" than a game.

Furthermore, the QTEs highlight the shallowness of one of the game's mechanisms: its take on "extra lives". During the more life-threatening QTEs, the player may flub, causing the protagonist to take a hit and then forcing the player to restart the sequence of QTEs again, while expending one of these "extra lives". If the player runs of "extra lives", it is game-over.

These "extra lives" would have been more useful if they allow the player to continue the QTE sequences without having to restart, which can be restarted anyway using a game-reload. They are handier when there are checkpoints (of sorts) in these sequences, which allow the player to restart at these checkpoints after expending an "extra life", but these sequences are so few and far in between; most of the sequences require restarting from scratch, or just outright lead to a game-over anyway if the player flubs.

Additional "extra lives" can be obtained by having the player characters collect what look like pendants and medallions, yet the significance of these objects do not appear to be acknowledged in-game in appreciable ways. There are remarks from the player characters on the matter of their faith and belief when they encounter these objects, but that is just about all there is.

MOVING AROUND IN THE ENVIRONMENT:

Outside of the game's many cutscenes, conversation sequences and of course QTEs, the player gets to move the player character about in a very limited level. Most of the time, the camera would be hovering behind the player character's back, giving a view of much of what is in front of the character. However, the camera cannot be independently controlled, which may cause problems when the player character's model visually obscures what the player wants him/her to interact with.

Interacting with something generally triggers an in-game cutscene with its own unique camera angles; this includes even simple acts such as opening doors and closets. Such a transition can seem overly dramatic at times, though to compensate, something interesting usually happens next.

STORY & CHARACTER DESIGN:

As mentioned earlier, this game has the theme of zero-to-hero. The protagonist appears to be just an everyday person, albeit a talented white-collar worker. Having the events in the game happen unto him is quite a lot for him to take; the writing for his lines and his voice-overs would make it easy for the player to empathize with him.

There are other main characters, namely two persons who are investigating the murders. The player will get to play both of them, but ultimately only one of them would matter; the other appears to act as a barometer for the consequences of the player's decisions, as well as a source of drama and a figurative report card later into the story. The game also portrays them as regular people who are facing extraordinary circumstances, which also make them just as easy to empathize with as the protagonist.

The other characters, especially the villains, tend to be a lot more difficult to appreciate, though they deliver on their primary roles. One of them has a lot of potential to be a sophisticated villain, what with his ancient past and his dealings with shadowy organizations, but ultimately he is just there to show how much the protagonist would develop over the course of the story. Another villain appears to be just there to portray the theme of the dangers of advanced technology, but does so well enough without appearing cheesy.

One of the side characters is of the archetype of the enigma, serving as a reason for the protagonist to keep asking questions about what is happening to him and around him. Seasoned film-goers may recognize more than a few elements from Japanese horror movies regarding this character though, giving the impression that the story-writing is not convincingly original. Nevertheless, there is a reward to be had from this character at the end if the player can put up with her clichéd appearances before that.

The best side character would be one of the protagonist's familial acquaintances and a certain former love interest. These characters act as emotional crutches as the protagonist's mind becomes frailer as events that he could not explain to them transpire in the early parts of the game. Interactions between them and the protagonist are perhaps the most emotionally uncomfortable parts of the game, though to describe more would be to invite spoilers.

Unfortunately, the abovementioned segments of the story would be its best parts to most people. What started as sort of a drama/horror thriller story eventually turns into one with more than a few inspirations from sci-fi action movies, which in turn becomes an excuse for the game designers to include the aforementioned QTEs. Having to trudge through obligatory QTEs can detract a lot from the experience.

GRAPHICS:

The graphical designs are the aspect of the game that opposes Quantic Dream's claim of it being an "interactive film" the most.

For its time, the visuals of the game were far from cutting edge. Although the models and environments in the game have plenty of polygons which allow for many animations, textures, particle effects and lighting leave much to be desired. In fact, they look rudimentary, even at the highest settings.

In the early parts of the game, the animations look quite convincing. Plenty of body language and facial animations, including accurate lip-synching, have been implemented in the character models, providing them with believable expressions and making it very easy for players to deduce their current mood.

Unfortunately, instead of delivering more on what has been done very well, the game has outrageous animations for the latter parts of the game. There are plenty of exaggerated backflips, storeys-high jumps and such other superhuman feats. Of course, they appear to have been adapted from motion-capture, but this only serves to highlight the inconsistency of the game's design direction.

Furthermore, these animations betray the limitations of the character models, such as how stiff they are at animating clothing.

The art design of the game could have been impressive, what with its variety of locales and next-to-no recycling of objects, but the abovementioned problems detract from its appeal.

It should be noted here that the game was designed for multiple platforms, including sixth-generation consoles. That Quantic Dream does not appear to have taken advantage of the more powerful computer platform to render better visuals for the game is a very glaring shortfall.

SOUND DESIGNS:

The aural ambience of this game can be said to be much like the animations. They start off with very believable noises, such as the bustle of a city and ambient sounds such as the wind, punctuated by the almost subdued crackle of things cracking in the freezing cold. Radio announcements comment on the progression of the climate change, giving a sense of brevity.

However, these are replaced with stupendous and wild noises that one would associate with sci-fi fantasy in the latter parts of the game, dashing the otherwise believable aural ambience of the game.

Fortunately, the music and voice-overs are a lot more consistent, sound-wise.

In the early parts of the game, the music mostly consists of moody and ominous symphonies, which befits the theme of mystery. In the latter parts, when the action heats up, much more exciting tracks are included in the mix, which somewhat compensate for the lack of graphical pizzazz in the thrilling parts of the game.

In fact, one could say that if not for the soundtracks, which are designed by veteran composer Angelo Badalamenti, the story would not be able to retain its atmosphere of cryptic thrill.

The voice-overs are performed by veterans of voice-overs in video games such as David Gasman, Paul Bandey and Barbara Scaff, so their voice-overs are expectedly appropriate for the occasion at the very least; otherwise, they are exceptional at portraying their characters and their current mood. Incidentally, many of these voice talents have contributed to Quantic Dream's earlier games, so some players may be familiar with their voice-overs.

CONCLUSION:

Indigo Prophecy, a.k.a. Fahrenheit in places other than the USA, appears to have a very promising story to deliver, especially if one considers its interesting prologue. However, a seeming lack of focus in design direction results in the game turning out to be all too different from the first impressions that it would create, especially considering the pervasiveness of QTEs. Adding to the doubts about the game designers' calibre is the game's lack of graphical pizzazz, which dashes their lofty claims of the game being as good as a gripping film against the figurative wall.

Indigo Prophecy is quite a flawed game that could have been so much better, though Quantic Dream's later offerings would show that it learns from most of its mistakes (but unfortunately not its preference for QTEs).