INTRO:

Stories with steampunk settings often rely on the interaction between fictitiously advanced steam technology and more believable story elements to generate appeal. More often than not, packing in more story elements would dilute the impact of the story-telling, or make it a chaotic mess. (The recent The Order 1886 comes to mind.)

Frostpunk is an example that works quite well. To mitigate the risk of a messy story, the developers (who made This War of Mine) focuses the story around a makeshift settlement and the struggles of its inhabitants. Conveniently, such a set-up sets the framework for making yet another resource management game – something that developer 11-bit Studios is decently skilled at.

PREMISE:

Frostpunk is set in a world with steampunk tech – and a descending Ice Age. Said Ice Age has doomed most of the world; the southern hemisphere is said to have been completely destroyed due to how unprepared it is for cold weather. Therefore, the game’s story focuses on the plight of northern westerners, most of whom happen to be curiously British.

That is not to say that there has been no attempt to write any story about the cause of the Ice Age and its consequences. There happened to be a caste of scientists, who have noticed the signs of the impending Ice Age months earlier and went up north to look for the cause. With the information from the boffins, wise governments have invested in secret projects to prepare certain sites up north for would-be refugees.

The projects installed “generators” into the sites. Incidentally, these generators are the survivors’ only hope. No other heat source is massive enough to sustain their lives and where they were, there was not enough fuel. Conveniently, many of these sites have considerable resources to be tapped too.

Expedient narrowing of scope aside, the plight of the survivors is as believable as it is incredible. Much of the gameplay will be about sustaining and improving the player’s settlement, while finding news about what is happening elsewhere and making preparations for emergencies and worsening weather.

PRESERVE THE TOWER:

The generator is a clearly steampunk edifice. It generates and radiates considerable heat, enough to stop the very air from being frozen. The one that the player gets happens to be in the centre of a considerable but limited amount of land for a settlement.

However, the generator only has its most basic parts. It has to be improved in order to prepare for colder days. Conveniently, the management of each settlement has the schematics for its improvement, among other things.

Anyway, the player is obliged to keep the generator running, while expanding its heating capability to support larger populations. Of course, greater heat production means more fuel consumption, so the player has to balance the development of the settlement between producing more coal and to support a higher quality of life.

The generator is tough enough to be set on “overdrive”. This increases its output beyond its safe design specs, at the cost of stressing it out. It can recover from the stress after “overdrive” is turned off; the recovery rate is the same as the stress build-up rate. The game will warn the player of critical stress build-ups.

If the player ignores the warning, the player eventually loses control of the camera, which then shows the generator blowing up. Obviously, if this happens, the settlement is doomed and it is (a much deserved) game-over.

POLICIES:

The gameplay element of “policies” is closely tied to the story-telling. Policies are the rules that the player could make for the settlement. The first set of these policies are under the “Adaptation” group, which is the first group that the player gets.

Some of these rules slant towards heartless efficiency, e.g. they weed out the infirm so that they do not become resource drains, or they squeeze more productivity out of people and exhaust them. Obviously, this will hurt people’s feelings a lot, but the settlement is more able to conserve its resources.

Some other rules are kinder, but they almost always lead to resource drains and opportunity costs. They give more hope to people, but they can harm the settlement in the long run by hurting its resource efficiency.

For whatever reason, these two kinds of policies are often mutually exclusive and cannot be rescinded. The narrative reason for this is not clear, but the gameplay-related reasoning behind this would be obvious to any experienced game consumer: it represents the tough long-term choices that the player has to make.

New policies can only be issued once every one-and-a-half days. Generally, it is in the player’s interest to issue them as soon as the timer refreshes, mainly because a policy that has been issued earlier can save the player from a lot of hassle.

SOCIETY-CHANGING POLICIES:

In most campaigns and scenarios other than the “Arks”, the game makes it clear that the post-apocalypse has destroyed all semblance of society as people knew it (especially in the “Refugees” campaign). However, not everyone is able to accept that survival is the only end-all-be-all goal, and there would be confusion over whether ‘survival’ means ‘mutual survival’ or ‘every man for himself’.

Hence, there is the narrative reason for implementation of additional groups of policies. When this moment comes, the player has to select one of two mutually exclusive groups: Faith or Order. Faith would give resolve to the people, whereas Order would give them discipline. Either way, gameplay-wise, the player is granted options that let the player manage discontent and raise hope.

Either group has a policy node that is not described with any text, but has a rather severe-looking symbolic design and is surrounded with a nimbus or aura. This one has considerable gameplay effects, and also represents a turning point in the narrative that would be described in the ending of a playthrough.

COAL:

Steampunk would never be complete without coal. Conveniently, the settlement is located on a site of abundant coal deposits. The ones who prepared the sites have mostly chosen well.

There are piles of loose coal, presumably dug and left behind by the scientists that came before the player’s survivors. These are limited, but are the easiest to gather.

Then there are the surface seams, which are the second easiest source of coal. These do require the use of the rare Steam Cores, which will be described later. These seams are also limited in amounts, but with six-digit amounts in most scenarios, it is unlikely that the player would ever exhaust them in any playthrough.

Finally, there are the deep deposits, which can be forced up using the “Thumper” devices. These are completely inexhaustible, but the coal is not automatically collected. Rather, it piles up and has to be manually collected.

In the “New Home” campaign, coal can also be collected from an outpost set up outside the settlement. However, the deliveries of these resources are intermittent, and the investment needed to get the outpost is considerable.

FOOD:

The survivors may seem rather hardy for humans, but they are ultimately mortal. They need food, without which they become angry. Of course, if they go long enough without food, they starve and die.

Food is obviously hard to come by in extremely cold weather. However, there are, curiously, many animals that have somehow survived the onset of the ice age. Thus, hunting is a reliable source of food, although the income of food from hunting is among the lowest.

Food can also be grown in “hothouses”, which are practically steam-fueled greenhouses. However, maintaining the micro-climate that the plants need requires the use of rare steam cores (more on these later). The hothouses also need temperatures at a minimum level, thus requiring heating even if they are being worked on by automatons (more on these later).

Food is always received raw, even from hothouses. Raw food is not dangerous, due to the unbelievable cold having preserved them. However, eating rock-hard raw food is unpleasant, and many would be understandably displeased at having to do so. People only eat raw food if they are starving, by the way. (There will be more explanation on hunger later.)

To have proper food, the raw food should be cooked. Somehow, every 2 units of raw food can be cooked into four portions of “standard rations”. The process also happens rather quickly at the Cookhouse, in which just five persons can cook hundreds of units of raw food in a single work shift. (Indeed, the player might want to rotate people in and out of the cookhouse early on in the game, when manpower is a problem.)

OTHER “RECIPES”:

There does not appear to any kind of food that is better than “standard rations”. That said, everything else is worse. After the player has unlocked these “recipes” through the system of policies, the player can have cookhouses make them instead.

There is sawdust-adulterated food, meant to fill stomachs while minimizing the consumption of actual food. Obviously, this is a really desperate thing to do, and it causes recurrent health problems in the long term.

Then there is soup, which is practically thinned food. It is nutritionally sufficient, but soup is not exactly something that the British people in this game like. Every time people eat soup, they accumulate discontent (more on this later).

Curiously, these two “recipes” are mutually exclusive to each other, for whatever reason; after unlocking one, the other is never available.

WOOD:

Wood is needed for just about everything, with the exception of the unlocking of certain techs about steel production and the building of steam hubs (more on these later). Therefore, the player will need a lot of wood.

Initially, wood can be found in loose piles; the player should get these and spend these carefully, because subsequent sources of wood need set-ups that consume wood too. Speaking of which, the player would later have to build sawmills to harvest the frozen trees around the settlement.

There is also the wall drill, which drills into certain spots in the ice walls around the settlement to get at frozen trees that had been trapped in them. The wall drills do require steam cores, however.

In the “New Home” campaign and any maps that have them, there are outposts that can be set up to deliver wood to the settlement. Like the coal outposts, these take considerable investments. However, as mentioned already, wood is used for just about everything, so the player will want to diversify sources of wood.

(There will be more on outposts later.)

STEEL:

Steel is implemented as a resource in order to complicate the management of resources that are needed to develop the settlement’s infrastructure. After all, steel has no more uses than wood. At least wood can be turned into coal, but the player is better off focusing resources on improving the coal mines. (That charcoal is not exactly coal is not an issue in this game.)

Anyway, steel is initially obtained from salvaging the wreckages that are around the settlement site. These wreckages have a notable tendency to generate injury-related events, especially if children have been assigned to them.

After the wreckages are gone, the player has to develop new sources of steel. That said, the investment for these new sources does not require steel, so the player could carefully spend whatever steel that remains while stalling for time. The opportunity costs can be considerable, but there are many early-game techs that require wood more than steel.

With the wreckages gone, the only source of steel in the settlement are the ore deposits. Most maps only let the player set up two steelworks next to each deposit, so the player’s supply of steel would be quite precious. However, there will still be times when the player might run up surplus production, especially when unlocking and developing mid-game tech.

LIMITED SOURCES OF RESOURCES:

In most campaigns, there are finite amounts of resources that can be harvested. The first examples of these are the piles of loose resources that can be retrieved with manual labour. There are also copses of frozen trees, which will eventually be removed as sawmills clear them out.

Then, there are the resource nodes. These are the coal seams, ore formations and – perhaps most interesting of all – dense copses of trees that are trapped in ice and have to be reached with the wall drill. These nodes are mid- and late-game sources of coal, steel and wood, respectively. In some campaigns, including the main one, the nodes contain a ludicrous amount of resources such that it is unlikely for even the most skilled manager to completely exhaust by the end of the playthrough.

DESTROYING TREES TO PLACE RESOURCES:

When placing buildings, the game will warn the player about any resource nodes being blocked or any resource fields being destroyed. This also applies to the placing of streets (more on these later).

That said, the only resource fields thus far are the frozen trees. As the game has warned the player, placing buildings or streets on frozen trees removes them outright, for whatever reason. (The removed trees are not saved for processing at the sawmills for later, by the way.)

Thus, the player has to balance the need to place those buildings against losing those trees permanently. However, it might be more prudent to do the former, especially if it is to develop the settlement’s economy as soon as possible.

STOCKPILES, DEPOTS & EXCESS RESOURCES:

Frostpunk is one of those games that do place a cap on the amounts of consumable resources that the player can hoard. Indeed, one of the buildings that is next to the generator right from the start is a stockpile. It can hold some resources, but if the player is running up surpluses, the player will need to build resource depots to hold them, especially for coal and food.

Interestingly, and perhaps tediously, resource depots do not hold all resources. Rather, after the player has built one, it has to be set to store a specific type of resource. Thus, as the resource expenditures and incomes wane and wax, the player has to switch depots to store other resources that have run up surpluses. Of course, this is different from other resource management games, but it is tedious.

If a depot is removed or switched, or the settlement gains a windfall of resources, the resource counters may overflow beyond their capacities. This does not cause excess resources to be lost, fortunately. However, any production of these resources at the settlement is stalled and cannot be continued until additional capacity has been obtained.

PAUSING DISMANTLING & CONSTRUCTION:

Conveniently, the game lets the player pause the construction, or dismantling, of buildings. This sends any person or automaton that is doing the building away, preferably off to more productive work. (Building structures and going to work has the same level of priority, by the way; whichever is present before the other takes precedence.)

Crafty players who do not mind the micromanagement can also place down buildings and then pause their construction, effectively turning these into resource banks. This is especially doable for steam hubs, which will be described later.

Besides, cancelling construction refunds all resources, but dismantling already-built structures does not.

UPGRADING STRUCTURES:

The player would eventually unlock techs that allow the construction of buildings that are practically straight upgrades of earlier ones. For example, there are the sturdier and better insulated shelters that supersede the tents.

Conveniently, the player can place the upgraded buildings on top of the obsolete ones. The people who have been assigned to the replaced building will be automatically reassigned to the replacement.

The cost for the upgrade depends on the difference between the amounts of resources recovered from dismantling the superseded building and the building cost of the replacement. Therefore, there is no cost difference from dismantling an old structure and building the new one in its place. Still, the player saves more time from upgrading old buildings.

The upgrading process takes the same time as building a new structure anyway. That said, in terms of task priorities, upgrading buildings has the same priority level as building a new one.

ALL BUILDING & DISMANTLING PRIORITIES DEPEND ON DISTANCES:

For better or worse, the building and dismantling of structures share the same task priority level. For further differentiation of priorities in this case, the game uses the distance of people or automatons to the buildings that are to be constructed. This is a very clumsy solution, because the game does not consider any other factors like the fuel meters of automatons.

STEAM CORES:

Steam cores have been mentioned a few times. These are rare, but technically they are there just to complicate the development of infrastructure, not unlike steel. Steam cores have no other uses, excepting an event involving the tinkering of automatons.

Anyway, steam cores are needed for the most advanced steampunk tech in the game. In particular, coal mines need steam cores, as do wall drills. All automatons also need steam cores.

Yet, steam cores cannot be made. In most campaigns and scenarios, steam cores are also finite in number, so the player has to decide carefully what things to use steam cores in.

Fortunately, steam cores can be completely recovered from dismantling anything that needed them in the first place. Things that do need steam cores happen to have rather long construction times, however, so the player will want to carefully plan the usage of cores in the first place.

DISCONTENT:

People who are experiencing stressful scenarios that are far beyond their imagination and control are more than likely to find someone to blame. Invariably, this would be their leader, because being a leader means being a lightning rod for the ire of one’s followers when things go wrong.

Cynical socio-politics aside, the game measures the dissatisfaction of the settlement’s people with a meter of “discontent”. The exact unit of measurement is unclear, but all the player needs to know is that the meter should be as empty as possible. If it becomes full, the people send the player an ultimatum, failing which the player simply suffers a game-over.

Even if the meter is not full, having any discontent will cause unpleasant events to pop up now and then. More often than not, the player is given a list of terrible options: temporarily forgo the manpower of an individual or a handful of them, spend precious resources to placate them, or risk further discontent.

The player could have been doing well to placate the survivors, but there will be events that pose dilemmas to the player; accidents are the most common of these. The player may have to take options that are practically resource drains, or leave the poor fools to their own devices, which of course anger people.

HOPE:

The coming of the Ice Age is not exactly something that the human spirit can overcome. Therefore, there would be a lot of people who do not have much hope that they could possibly survive what comes. However, the survivors of the player’s settlement have arrived there after a long and gruelling trek, so they have hope that they could pull off another miracle.

On the other hand, the survivors came to the settlement on a proverbial road that was paved by the frozen corpses of their compatriots. They know that, and all it would take is just a few more deaths to snap their resolve like a twig. Therefore, the player will want to keep deaths at a minimum.

That said, any of the player’s decisions that make people aghast or horrified would diminish hope too. Some are not too serious, like the early-game policy of having children take up “safe” jobs like hauling things around. Some are serious, like preserving corpses in a pit of snow so that their organs can be fished out later. (Never mind that the frost would have damaged the organs.)

If people lose hope, they start abandoning the settlement, especially if there is also considerable discontent and not enough food or warmth for everyone. These people will not return. Manpower is especially finite, so the player will want to maintain a sufficient level of hope.

Early in the playthrough, there are not a lot of things that can raise hope. Therefore, if the player screws up and gets a number of survivors killed, it would be hard to regain one’s footing.

HUNGER:

Hunger is obviously any human’s concern. By default, eating occurs once per day, if there is a functional cookhouse around and there are food rations available. Speaking of the cookhouse, it does not need to be operated by anyone; people would go there anyway to eat.

Going to eat and eating takes time, but they generally do this during their off-hours. This is because of the priority coding for eating; it is at the same level as working and building/dismantling structures. Therefore, if the player has set up structures or streets to be built, they will do these first before eating. This is convenient, especially for a player who wants to accelerate infrastructure development.

If there is no functional cookhouse, people go hungry, even if there are food rations. This can be exploited to stretch food rations, since hunger meters are completely reset upon eating. That said, the hunger meter of any person is never shown to the player, but the game does track the meter for each person in the settlement.

People only drop everything else to go eat when they are starving. As mentioned earlier, they will eat raw food if they could not eat food rations; food rations can only be served through a functional cookhouse.

WORKPLACES:

Most of the gameplay that is associated with the settlement’s economy revolves around the management of workplaces. These workplaces can be the piles of resources lying about the settlement at the start of the playthrough, and the buildings that the player would have later.

The player assigns humans or automatons (more on these later) to the workplaces to make them useful. Despite the use of clearly steampunk technology, there is no integrated automation of work-places, other than to attach automatons to them.

Some workplaces have their locations fixed, such as the aforementioned piles of loose resources and the deposits of coal and iron ore. The other workplaces are built at locations that the player specifies, preferably for optimal travel paths.

PRIORITIES ON WORK ASSIGNMENT DEPENDENT ON CURRENT DISTANCE:

Like building structures, work assignments have the same priority level as each other and further differentiation depends on the distances of people or automatons to the workplace. Again, this is a clumsy solution.

CRUDE ASSIGNING BUT SPECIFIC DISMISSING:

There may be a design issue in how 11-bit implemented the controls for work assignments and the controls for dismissing individuals from workplaces.

Work assignments are implemented through a simple button-oriented interface that allocates any unemployed individuals to the workplace – emphasis on “any”. As mentioned earlier, the game simply searches for unemployed individuals that are the closest to the workplace.

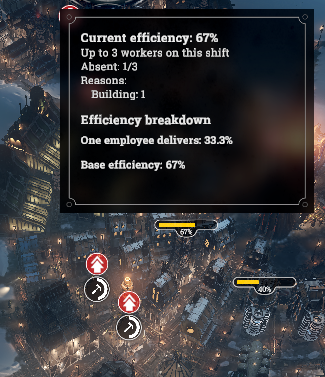

The player has no further control, so the game could select individuals that the player does not want, like people in medical treatment or automatons that are going to refuel. These individuals simply would not contribute to production in the short-term.

On the other hand, the player is shown the list of individuals that have been assigned to the workplace. The player can dismiss specific individuals, which helps a lot in getting people that are unproductive out of the workplace.

However, assigning a replacement is difficult, due to the aforementioned distance-based. The player has to wait for the unwanted individual to move further away from the other unemployed individuals before allocating a replacement. Otherwise, the same ejected individual will be reassigned again.

HEALTH & WORKPLACES:

People can die – something that the game would be happy to remind the player about. In Frostpunk, one of the ways that people can die is from getting sick.

In truth, any individual human does not have his/her own health meter in the coding of the game, unless what was done for hunger. Rather, a person’s health status depends on the conditions of his/her workplace and the time of the day.

Specifically, the game checks the conditions of the workplace throughout the workplace’s shift. If they had been terrible throughout most of the hours of the shift, it will randomly assign health issues to the people who work at the workplace. When these health issues will be applied are unclear, but they tend to occur sometime after midnight.

This is so, regardless of how long that person has worked at the workplace. For example, a person can be assigned to a terrible workplace half an in-game hour to the end of the shift, but after midnight, he/she may be hit with a de-buff.

The times when the game makes the checks on workplace conditions are unclear, and may even be randomized; I have done a lot of experimentation on this, and they are not consistent. Suffice to say though, having a workplace with bad conditions staffed for more hours in the work-shift makes sickness more likely to happen.

HEALTH & HOME:

During their work-shifts, the health of the survivors depends on the conditions of their workplaces. Outside of their work-shifts, their health depends on the conditions of their shelters – if any. This also applies if they have spent the entire night building a structure.

As with workplaces, the game will make checks on the conditions of the shelters and assign sickness de-buffs accordingly. Fortunately, the game does try to fill shelters with good conditions first, before using the shelters with less-great circumstances.

If a person does not have any shelter whatsoever, he/she is in trouble. In this case, the game will track how long any individual has gone without shelter, and inflict de-buffs sometime before dawn. This will happen, even if the person has been lingering in places with considerable warmth, like right next to the generator. This also applies if the person’s shelter is being upgraded, so any upgrades to shelters should be prioritized first.

CANNOT REASSIGN HOMES OR EJECT PEOPLE:

The player cannot assign people to different shelters or dismiss people at shelters like the player could with workplaces.

It is unclear as to why the player is not allowed to do this, but the aforementioned automatic allocation of people to shelters based on the conditions of the shelters would suffice as an excuse.

GOING TO WORK IS ALREADY THE SAME AS WORKING:

Distances from shelters to workplaces are not an issue, because the “going to work” task already automatically causes the workplaces to start producing.

To elaborate, in the case of people or automatons that have just refuelled, their workplaces are considered to be already being worked on as soon as they initiate their “going to work” task. This is unbelievable, but it is very much a blessing of convenience.

WORKPLACE & SHELTER TEMPERATURE:

A workplace may be about shovelling coal. Another might be about working machinery that extracts iron ore. One shelter may be just tents, whereas another is a better constructed one with wooden walls and metal reinforcements.

Yet, despite the myriad of workplaces and shelters, there is only a single building condition that matters to the health of people: temperature.

The temperature is represented as a metered rating. The highest rating, “Comfortable”, does not cause any problems. However, “Comfortable” ratings are not so easy to achieve, at least not before the player figures out how to manage the heating of buildings.

Any lower rating can cause problems, including the second-highest rating that is “Liveable”. The lower ratings can be brutal, especially “Freezing”, which can outright cause grave sickness and sometimes frostbite leading to amputation. There will be more elaboration on health complications later.

MOVING ABOUT IN THE COLD:

Strangely, humans moving about in the cold does not matter in the gameplay; only their workplace and home temperatures matter. Therefore, a person that is unemployed, i.e. not assigned to a workplace, but has been building structures throughout most of the day would not seem to be affected much if he/she has already been assigned to a well-heated shelter. However, this also means that the ambient temperatures of the outdoor places that a person has gone to or is at will not matter at all.

SICKNESS & HEALING:

Despite the various problems that could affect the health of people who live in the cold, Frostpunk simplifies all health problems to just “sickness” de-buffs.

When a person gets a de-buff, the game begins to track his/her condition, creating counters just for him/her. These counters will determine whether this person heals or gets worse.

A person has to receive treatment from medical facilities to become well. Gameplay-wise, his/her sickness meter recedes as long as the facility that provides the treatment is still operational.

The task of “going to treatment” appears to stall the advancement of the sickness meter; this is something that can be confirmed with ruthless experimentation. However, healing will not start until the patient has the “in treatment” status.

If the medical facility is dismantled, disabled or loses its staff, the patient has to go to another medical facility to return to “in treatment” status.

A patient in treatment will not work, but will take up a work slot anyway. Therefore, the player might want to replace him/her with an unemployed person.

NO CONTROL OVER PATIENT ASSIGNMENT TO MEDICAL FACILITIES:

The player has no direct control over which facility that the patient would go to. The game does use the same scripting as that for the allocation of people to shelters, i.e. the medical facilities with the best conditions will be filled first. In the case of facilities with similar conditions, distance is the factor that is used for further prioritization.

However, since “going to treatment” is not the same as “in treatment”. A sick person may take a long time to reach the facility, meaning that a lot of time might be wasted waiting for this person to arrive. Furthermore, sick persons move slower than healthy ones. Prioritizing distance in the first place would have been wiser, if only so the healing process can begin as soon as possible. The player can worry about improving conditions at the medical facility later.

Better yet, it would have been better to give the player direct control.

REGULAR SICKNESS & MEDICAL POSTS:

A person with the regular sickness de-buff eventually becomes worse if he/she is not treated. However, the regular sickness de-buff, if untreated, does not prevent a person from continuing to work and does not appear to affect his/her performance. On the other hand, working while sick will accelerate the eventuality of the sickness worsening.

Regular sickness can be healed with the medical post, the rudimentary medical facility. Healing with medical posts takes quite a while, so the player might want to consider getting the more effective infirmary as soon as possible.

GRAVELY ILL PEOPLE & INFIRMARIES:

The worse grade of sickness is “gravely ill”. For simplicity’s sake, grave illness is presumed to be frostbite or severe pneumonia, even if the cause might have been something else.

It should be pointed out here that as much as the player tries to manage heating, there will be people falling gravely ill due to severe bouts of cold weather that can overwhelm any heating. Therefore, Infirmaries are a must in any playthrough where the player wants to minimize the body count.

Gravely ill people do not recover completely when their sickness meters tick down to zero. Rather, their de-buffs are replaced with the regular sickness one. This is important to keep in mind, because infirmaries will swap out patients with regular sickness for those with grave ones, just so that the latter can be treated. If there are no patient slots for the regularly sick ones that were booted out, they can get worse, resulting in a vicious cycle that ties up the infirmaries.

Outside of treatment, gravely ill people cannot do anything other than rest and eventually die. Without infirmaries or a care house, gravely ill people have to live at medical posts, thus taking up one patient slot indefinitely. Alternatively, there are two nasty policies that let the player reduce the number of gravely ill immediately; one gives the ability to kill off half of them while immediately improving the rest, whereas the other turns most of them into amputees in return for ‘healing’ them. (There will be more elaboration amputees later.)

CARE HOUSES & PALLIATIVE CARE:

In lieu of the aforementioned nasty policies, the player can build care houses that take up considerable space. The care houses can house all sick people, including the gravely ill ones; the latter are prioritized over the regularly sick ones. They will not get better if they do not get treatment, but they will also not get worse. They also consume half of their usual amounts of food, for whatever reason.

What the game does not clearly inform the player about is that in the gameplay, these care houses count as shelter buildings instead of health-related buildings. They can be affected by the area effects of hope-raising and discontent-reducing buildings, specifically those made available by the Faith or Order policies.

AMPUTEES & PROSTHESES:

Gravely ill people may end up being amputated at the same time, if their cause of illness is freezing temperatures. Amputation is also the consequence of events involving industrial accidents and the aforementioned radical treatment (i.e. amputation) of the gravely ill.

Amputees cannot do much of anything. They are permanent resource drains until the player has issued the policy of making prosthetics.

It is narratively unclear as to why this policy issuance is required, because the technology to make them should have been available from the start. Besides, the player has to unlock the tech to make factories, and then have the factories make prosthetics. They also cost a considerable amount of steel. The amputees still need to travel to a medical facility for installation, and this can take a while because amputees move very slowly.

Gameplay-wise, this protracted series of requirements for making amputees useful again are there to make poor decisions costlier. If the player has been mindful of people’s safety and health, there would not be many amputees.

UNLIMITED AMPUTATION:

Amputees that receive prosthetics are converted back into regular people, meaning that they can end up being amputees again, regardless of how many times a person has been amputated. The game does not keep track of the number of amputations and prosthetics that a person has received. Thus, gameplay-wise, prosthetics act more like “cures” to working disability.

TYPES OF INDIVIDUALS - OVERVIEW:

There are several types of inhabitants at the settlement. Knowing what each can do or cannot do, and how they do what they can do, is a major portion of the gameplay. One small segment of the user interface is dedicated to listing the numbers and types of individuals that live in the settlement.

Although the game will track certain things about them, like the aforementioned sickness of ill people and the hunger of people, there are no other statistics. Individuals do not gain experience points and become more skilled. There are no gameplay elements that make specific individuals functionally different from individuals of the same type.

WORKERS:

Workers are the regular working adults of the settlement. They can do most jobs, though there are also some jobs only they can do, such as hunting for food. The bulk of the working adults in the player’s settlement, at least in the main campaign, would be workers.

ENGINEERS:

“Engineers” is the catch-all phrase for working adults who happen to have more technical skill than the others. Despite their name, engineers can work at medical facilities, effectively fulfilling the roles of doctors. This is likely just a gameplay design, because there is no narrative explanation for this.

Engineers can do most of the jobs that workers can do too, but generally, the player will want to have them work jobs that are unique to them. Chief of these is the job at the workshops, which unlock technology that the settlement needs in order to be more productive and resilient.

Ultimately though, the unique jobs are the only things that differentiate engineers from workers.

CHILDREN:

By default, children cannot work at all. Early on in a playthrough in the main campaign, the player has to make a decision on what to do with them. Delaying this decision can be costly in the long run, because without this, children are outright resource drains.

Firstly, there is the policy to shield children from any hard work by building a care shelter for them. This makes children more difficult to get sick, and their parents, if any, will visit them after work hours to give the settlement a small but regular boost of hope. Obviously, if any of the children are orphans, they will not contribute any hope boosts.

There is a policy down this path that educate all children to be assistants that can perform the jobs that are unique to engineers. These jobs are also not likely to get children in trouble.

Secondly, there is the policy of having children work relatively “safe” jobs. This comes with a significant hit to hope and a rise in discontent (perhaps deservingly so), but the children can now work vital jobs, like gathering loose resources and collecting coal released by the coal thumper.

The player can also take a step further down this line by enabling all worker jobs for children. This exposes them to the same risks, and having children get harmed happens to reduce hope and increase discontent more than harmed adult workers would.

NO ACTUAL EXHAUSTION METERS FOR HUMANS:

People have hunger and sickness meters, but no meters for exhaustion. The player might learn this from observing how people that had been working shifts had also been building structures outside their work shifts, and then continuing their work-shifts afterwards.

This is unbelievable stamina, but the developers have implemented this convenient design gap in order to simplify the gameplay. Indeed, the game would have been quite an ugly mess if this was the case.

That said, the extended (14-hour) shifts do not cause any long-term health problems; they merely cause indefinite discontent that can be handled with certain policy-unlocked buildings

RANDOM DEATHS FROM 24-HOUR SHIFTS:

Yet, despite the seeming lack of any tracking of exhaustion, there are attempts to implement health-affecting setbacks that are associated with exhaustion. This can be seen in the use of the 24-hour work shift, which is enabled through one of the policies in the Adaptation group.

The 24-hour shift, as its name suggests, forces the people who work at the affected workplace to continue working for 24 hours starting from the time when the order is issued. During this 24 hours, there is a chance that one of them dies from “exhaustion”. It does not matter whether the player has swapped people out of the workplace for supposedly fresher people; whoever happens to be there when the game decides to inflict the death risks being chosen.

Upon realizing this, this can seem like a cheap way to implement the disadvantages of certain decisions because the game lacks the mechanism to deal with it in a convincing manner.

AUTOMATONS:

Automatons are massive robots that function quite differently from the humans. The first and main difference is their movement; they do not use the same pathfinding scripts as the humans do. This will be described further later, together with one of the complaints about Frostpunk.

Anyway, automatons can do most of the things that workers can do. They can later be upgraded to do the work that even engineers can do, like operate infirmaries and workshops. The narrative does not describe how an automaton with a body that is the size of a house and long spindly legs can work any facility, but presumably the facilities have steampunk tech that is designed to interface with them. (There is also the fact that all of the automatons have the same standardized design.)

Each automaton can theoretically do the work of ten men, albeit at 60% efficiency initially. It will never achieve 100% efficiency, likely due to their size and relative clumsiness. However, there are upgrades that can be unlocked for them and at least one event that can lead to an efficiency upgrade that cannot be obtained any other way.

Automatons also happen to completely occupy workplaces, meaning that no human could work in the same place as them. This is just as well, because automatons would be useful to workplaces that tend to be far away from heat sources, such as the wall drills.

The main appeal of automatons is that they can work round the clock and are of course immune to the cold. Even if they have to refuel, the facility that they are working continues to run anyway. This is likely another design convenience, not unlike “going to work” counts as already working the workplace, as mentioned earlier.

REFUELLING:

Speaking of refuelling, the automatons appear to draw steam from any steam hub or generator, as long as the generator itself is turned on. There does not appear to be any cost for refuelling; they do not consume coal, and they do not appear to impair the function of the generator or hub. As for their refuel frequencies, they do this twice per day, but when exactly is unclear.

The player is never shown their fuel gauges. There is only the indicator light at the top of their hulls, which changes colour when they need a refuel, but the colour changes are not gradual and they are of the same hue.

However, the refuelling animation is very long. The automatons have to set themselves at the correct facing of the generator, or exactly over a steam hub, and settle down. Any interruption causes the refuelling process to be reset, and they have to start over.

This is not an issue if they are already working a facility; as mentioned earlier, their production continues as long as they are not reassigned.

However, if they are in need of a refuel soon and they are reassigned, they will not contribute to production until after they have refuelled. This can be annoying.

(BAD) PATHFINDING:

One of the biggest problems with games that have moving units is pathfinding. Specifically, pathfinding scripts are for in-game characters that need to move from one point to another. As simple as this sounds, no game developer has ever managed to develop scripts that are reliable and efficient, unless the map is completely empty and units can clip through each other.

Unfortunately, Frostpunk has lousy pathfinding too.

People are already so slow with their walking. Even if they aren’t wading through snow, they walk with a sluggish pace. Having poor pathfinding stacked on top of this makes waiting for them even more unpleasant. They seem to use the streets most of the time, but this is not consistent. They also never take the shortest path, even though moving through cold places does not affect them, as mentioned earlier.

Automatons move faster than humans, thanks to their big size and quadruped build. Due to their height and spindly legs, they can walk over just about any building. However, they never walk straight between one point and another. This is because they follow circumferential and radial lines (more elaboration on this later), which also means that they always have to include at least one 90-degree turn in their paths.

Unfortunately, quite a number of gameplay elements are affected by this bad pathfinding. For example, eating and getting medical treatment will require individuals to get to where they need to be; their bad pathfinding can mean that they waste a lot of in-game time moving and thus delaying their return to productiveness.

WORKSHOPS & “RESEARCH”:

One would wonder how extensive steampunk tech is in Frostpunk when most of what the game would show is snow and desperate survival. Most of the first few buildings, other than the generator, do not look convincingly steampunk either. The exception is the workshop, which definitely looks outlandish.

The workshop is presumably where engineers produce the parts that are necessary for upgrading the hardware in the settlement. Gameplay-wise, it enables the tech-unlocking system that is so prevalent in management and strategy games these days.

All the player needs to unlock the system is one workshop. Manning the workshop is needed, if the player actually wants to unlock tech.

Each tech shows its costs, together with what it unlocks. Conveniently, the cost for what a tech unlocks is also shown, which helps a lot when planning the development of the settlement.

The nominal time needed to unlock the tech is also shown. This is important, because time is that one resource that the player would not be getting back.

Indeed, the endgame of any non-Endless playthrough will come, no matter how much the player tries to stall for time. Therefore, the player has to try to make the most of any time elapsed by maximizing the outputs of the workshops.

OUTPUT OF WORKSHOPS:

Speaking of which, the first fully manned workshop gives the default rate of unlocking techs. To increase the rate, the player needs to build and man more workshops. However, the second workshop only increases the rate by 30%.

Each fully manned workshop afterwards has diminishing returns, down to just 10% for each workshop. Even so, tech unlock times can stretch into many hours, so 10% can still be considerable. Therefore, the player has to consider the trade-offs for using engineers in other workplaces against having them accelerate research as much as possible.

Perhaps the best tech that the player should strive for is “Engineer Automaton”, which lets automatons do the work that engineers do. Wise players would place an automaton in one workshop, just so that tech unlocks can happen outside of work-shift hours.

CIRCUMFERENTIAL & RADIAL GRID:

The settlement’s space is divided into a grid with circumferential and radial cells, otherwise known as a circular grid. The actual size of each unit cell is actually quite small; the player cannot see this, even if the player is placing the smallest buildings in the game. Bigger unit cells, which are made from smaller units cells, are shown if the player is placing larger buildings.

The actual unit cell size can be estimated by observing the movement of automatons. As mentioned earlier, automatons move along circumferential and radial lines; these lines are laid across the edges of the actual unit cells in the grid.

PLACING BUILDINGS:

When the player wants to place a building, the game automatically tries to fill in as much space as possible with the building’s base. The game may also use larger unit cells for certain facings of the buildings, in the case of larger buildings. In particular, the game will try to fit buildings in between stretches of streets. This can be irritating to players who are anal-retentive about space usage.

Anyway, the buildings’ actual appearances are always the same, regardless of the number and size of the unit cells that the buildings are taking up. The placement of buildings in concentric circles around the generator is only apparent if the player zooms out and examines the shapes of the settlement.

Conveniently, the game will inform the player of what is going wrong if the player could not place a building, and also what would go wrong if the player places it. For example, if the placement of a building would overlap with frozen trees, the game warns the player that the frozen trees would be destroyed. That said, if the player places the building anyway and cancels the construction of the building, the trees will not return.

STREETS:

Streets are paths laid down along the edges of the unit cells. They do not take up space, but they will destroy any trees that are in their way; the player is not warned about this, unlike how it would be with buildings.

Observant players might notice that snow does not accumulate on top of the streets. This is because the streets also contain pipes that channel steam from the generator, hence melting any snow on the streets. Any building that requires power from the generator thus must need streets reaching up to it, otherwise it is useless.

If people are placing the streets, each person will lay down one unit length of street. Which unit length is not specified to the player, and the sequence that the people follow are not clear either. This can result in very inefficient execution of the player’s construction plans.

PAVING & DISMANTLING STREETS:

Although the streets contain pipes from the generator, streets only require wood to be placed. Of course, this is just a gameplay balance design; having to spend steel to place streets can be prohibitively expensive.

Anyway, the paving of streets takes time, because they need to be placed by people or automatons. The dismantling of streets happens immediately, which is convenient.

Dismantling streets returns some wood, but not all of that which has been spent on placing streets.

TASK PRIORITY FOR PAVING STREETS:

Paving streets shares the same task priority level as having already been working at workplaces. In other words, people or automatons that are already working at workplaces will not leave in order to build streets.

However, paving streets takes precedence over anything else with lower priority than having already been working. People that are going to eat, going to work, going to get treatment, going to build structures, or already building structures will stop whatever that they are doing to build streets.

Automatons that are going to build structures will also stop doing so to build streets; this is bad, because their animations for street placement take quite a long time. For better or worse, the automatons will stop building streets if there are people that would do so.

Perhaps the developers have implemented this because they believe that paving streets is very important. Indeed, it is very important, but only in the long term. In the short term, the player might need to have people and automatons go to work in order to maximize resource gains for the day.

This task prioritization means that the player cannot place new streets until he/she is certain everyone is already working. Unfortunately, there is no screen in the user interface that lets the player know the current task status of each and every person or automaton. Furthermore, where buildings that are being constructed would at least show who is building it, streets do not.

CATEGORIZATION OF BUILDINGS:

Most competently designed management games have user interfaces that show the categorization of facilities or buildings that the player would be placing down. Frostpunk has it too, but its categorization of buildings in the building menu does not exactly match the categorization of buildings in the research menu.

For example, unique buildings like the signal beacon and the factory are simply lumped under the “Tech” tab in the building menu, whereas the research menu lumps their associated techs under “Exploration & Tech”.

The clumsiest organization of the buttons under the building menu is that for the “Resource” tab. The list of resource buildings is very long, and the player has to navigate them through a horizontal arrangement.

BUILDING SIZE AND IMPEDANCE:

A trait of buildings that is not told to the player is their impedance to movement. Certain small buildings, such as all shelters and resource depots, do not impede movement; people simply clip through them and automatons walk over them. The ones that are noticeably tall and/or large, like the workshops and the factory, prevent any movement through them.

This information should perhaps have been made visible to the player, because they mess up the already lousy pathfinding scripts of people and automatons.

EVENTS AT THE SETTLEMENT:

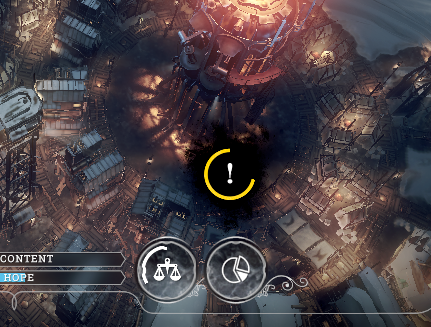

Occasionally, events pop up in the settlement. These are represented with ink blotches and a symbol, together with a diminishing ring that shows the countdown to when the player will be forced to address this event.

The symbol is a good hint on what to expect from the event. For example, exclamation marks suggest a warning or alert of sorts. For another example, icons of people suggest a request from them. If the player has a good idea on what an event is, the player might want to stall for as long as possible to get things ready to address the event.

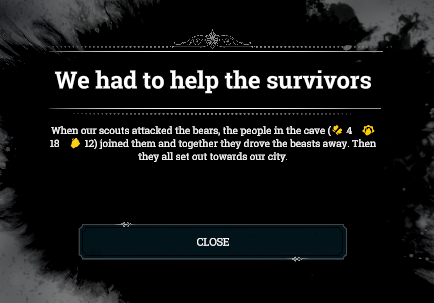

Some of the events that the player would get are troublesome. These pose a dilemma to the player, often the kind that is between a rock and a hard place. Some others are more pleasant, like rewards for having made certain decisions earlier.

REQUIREMENTS FOR EVENTS:

There are requirements for events to happen. The requirements are never shown to the player, but the causes will be described when the player reads the writing for the events.

For example, for the event that is about the people’s request to be exempted from extended shifts for a few days, there have to be workplaces with extended shifts already.

If the player habitually reloads game-saves, he/she might observe that these random events occur at specific albeit randomly assigned times. The player might be able to avoid certain events by addressing their causes before they even trigger.

For example, the event that is about an automaton stepping on a person on the streets will only happen if there is a person that is outside of buildings and is close to an automaton when the game makes a check at specific times. If the player could have everyone stay in buildings at the time, the event will not happen.

EVENT DECISIONS:

Some events are just there to notify the player that something has happened. Others require the player to make decisions – often give-and-take ones. Fortunately, the player is forewarned about what would happen if the player takes a decision – if it is available.

Some decisions are not available, because the player has yet to achieve the requirements for having them available. Some of these can be seen in the events concerning the “Londoners” in the main campaign. Unfortunately, the player is not told about the requirements for decisions that are not available.

SIGNAL BEACON:

Soon after the start of any playthrough, the player has to build the signal beacon. It is vital because it is needed to unlock a significant part of the gameplay.

The signal beacon does have some gameplay problems though. One of them is at least told to the player, namely its rather expensive cost, which can match those of late-game structures.

The other problem is not told to the player. After it has been built and expeditions have been launched, the signal beacon has to stay where it is; the reason is that the expedition teams need to be able to see the beacon in order to triangulate their position. Therefore, if the player has not planned its placement well, it will impede the expansion of the settlement.

EXPEDITIONS:

After the signal beacon has been placed, the player can send people out on expeditions into the “Frostlands”, which is what the survivors call the surrounding region. The expedition must be composed of five people, so the player should be careful about when to send people out, lest the player lacks the manpower for production. Nevertheless, the payoffs from expeditions can be significant, as will be described shortly.

When an expeditionary team sets out, it moves across the Frostlands in straight lines. These lines are just abstracts, because the actual distance to and fro any two pairs of locations have already been pre-determined in the design of the campaign.

The actual distances or the equations that calculate them are not shown to the player, however. Rather, the player is shown the time that is needed for a team to reach a location.

The expeditionary teams are described in-game as “self-sufficient”. Gameplay-wise, this means that the player does not have to worry about their health and hunger. This might seem unbelievable, because the Frostlands do seem rather inhospitable. Still, it is convenient.

SENDING SICK OR HUNGRY PEOPLE ON EXPEDITIONS:

Observant players might notice that people who go on expeditions are practically removed from the list of people whose conditions that the game is tracking. This can be used for an exploit, which is sending sick or hungry people on expeditions. Since the conditions of people on expeditions are not tracked, hungry or sick people would not have their conditions worsen.

On the other hand, when these people return and their teams are disbanded, their conditions also return and the game continues to track them. Therefore, the player might want to have food and medical services ready for them.

However, this will not work for sick people that are already in treatment; this is because undergoing treatment has higher priority than the task of “going on an expedition”. They only leave after they are better, and would somehow join up with their compatriots, wherever they are in the Frostlands. Therefore, as heartless and silly as this sounds, the player might want to disable medical facilities to force them to leave.

LOCATIONS IN THE FROSTLANDS & SCOUTING:

The blizzard and snow make it difficult to see anything along the ground, and the signal beacon can only see so far. Therefore, initially, only a few locations are shown in the Frostlands. To find more locations, the player needs to scout out existing locations, preferably with a scouting team. If a location has been pre-designed to reveal other locations, it will do so after it has been “explored”. There will be more on exploration later.

An expeditionary team can reach a location but not explore it. The contents of the location will be revealed, together with the other locations that it would reveal once explored. Even if the player withholds its exploration, the location is considered as having been scouted.

After a location has been scouted, it becomes easier for a scout team to reach it again. One of the few practical reasons to do this is to park a scout team close to the locations that are furthest from the settlement, so that it can reach newly revealed locations afterwards instead of starting its journey from the settlement.

Incidentally, if a scouting team starts its journey from the settlement, the actual distance from the settlement to a newly revealed location would also have included any changes from already-scouted locations. The exact changes are not shown to the player, however.

EXPLORING LOCATIONS & DECISIONS:

As mentioned earlier, after a location has been scouted, its contents are revealed to the player. Some of these contents may be resources that the player might want.

When the player makes the decision to explore a location, the player is pushed into a screen that the player cannot exit without having made a decision on what to do with the things at the location. Each location has its own unique set of decisions, if there are more options than just pocketing whatever is there and moving on.

Few of the decisions will affect discontent and hope back at the settlement. This is perhaps understandable, as they happen away from the settlement.

RESOURCES FROM EXPLORATION:

The resources that the expeditionary teams found would be collected and stay with the teams until they return to the settlement. Somehow, there is no limit to the amounts that they can carry.

However, there is a risk of losing them. Although the expeditionary teams might not die from sickness or hunger (as unbelievable as this seems), there are locations with risky exploration options; the player is forewarned about them with ominous symbols next to these options. Unfortunately, an RNG roll decides the outcomes of these risky options, so the player might have to resort to game reloads or even re-launches to get a favourable outcome.

OUTPOSTS AND OUTPOST TEAMS:

There are two types of expeditionary teams: scouts and outpost teams. Scouts are composed of five people, whereas outpost teams have ten persons each. Scout teams are meant for exploration.

Outpost teams are slower than scout teams, presumably due to the greater amount of gear that they are carrying. As their name suggests, outpost teams are meant to be used on locations that have been identified as viable outposts, if the campaign has been designed to have them.

The narrative may state that some locations already have amenities that can be used to harvest resources, or they have structures that are so extensive that they cannot be salvaged completely in a short time. Thus, outposts can be set up in these locations to draw more resources from them.

Thus far, I have yet to come across any events involving outposts. There may be a lost opportunity to introduce more complications into the gameplay, but perhaps even the developers are wary of doing so after having implemented so many for the settlement.

OUTPOST DELIVERIES:

After establishing an outpost, an outpost team splits into two sub-teams: one works the location, the other delivers to the settlement. The rate of deliveries are purportedly once per day, but it is unclear when exactly during the day that they would be sent out. In fact, the player is not given any timers at all.

If the settlement’s resource stockpiles have overflowed, outpost deliveries of the surplus resources will be stalled, just outside the settlement. The outpost will not be able to send out new deliveries either.

Late into a campaign that happens to have the “Great Storm”, outposts can be outright destroyed together with the teams if the player does not get them out of the way quickly enough. The Great Storm moves hour by hour across the Frostlands too, so the player will want to get them out of the way early.

WEATHER AND AMBIENT TEMPERATURE LEVELS:

The incredible cold brought with it a significant fall in overall temperature levels. The exact cause is mentioned as not being clearly known in the narrative of the game, which makes for convenient inexplicability in one of the game’s main gameplay elements, which is the significant changes in ambient temperature.

Anyway, the ambient temperature is shown as a temperature reading at the top centre of the screen. This is just for visual flair, because the actual gameplay design for ambient temperature is implemented in the form of “temperature levels”.

Despite their lack of knowledge about the cause of the incredible cold, the scientists in the world of Frostpunk have somehow come up with a way to predict changes in ambient temperature. This is represented in the gameplay as a meter that ticks away the progression of the days. The meter also has symbols that indicate when the temperature rises or falls, and their magnitudes in levels.

Most campaigns have pre-determined rises and falls. These are mainly there to challenge the player’s ability to make preparations. Being able to survive temporary falls is a great feeling the first time. However, observant players might notice that there is just no other practical solution other than to get heating or insulation techs unlocked. This can give the impression that the player is solving puzzles instead of making survival plans.

INSULATION AND HEATING LEVELS:

Insulation and heating are needed – often together – to resist the cold. The performance of insulation and heating are also represented in temperature levels. This eases the calculations that the player would make in determining how much insulation and heating are needed.

Some buildings come with insulation, while some others do not. For example, the basic shelters, which are tents, lack insulation. For another example, the workshop is an early-game structure with two levels of insulation, thus giving more protection to the engineers that work in them than their tents ever would.

Later, the player can have heating installed in some buildings, mostly workplaces. This raises temperature levels, at the cost of using coal. The player has to turn off and turn on each building’s heater, so this can be a hassle at times. Steam hubs are a more convenient solution, because of options to control their activation schedules. The heating from steam hubs and the generator happen to stack with insulation and installed heaters.

STEAM HUBS:

Steam hubs draw steam from the generator through the streets. Incidentally, they can only be placed on streets. Fortunately, they can be placed on streets that are still under construction. As mentioned earlier, the player can also pause their construction to “bank” steel.

Anyway, the main reason to have steam hubs is for them to duplicate heating from the generator. Their range is small, but it is still enough to heat several buildings, if the player is shrewd with their placement.

As mentioned earlier, automatons refuel by drawing steam from the generator or steam hubs. Apparently, they can even do so from steam hubs that have yet to be built. Thus, the player could place unbuilt steam hubs with paused construction close to their workplaces, if only to bank surplus steel and to shorten the automatons’ refuelling distances.

Compared to installed heaters, heating from steam hubs almost always costs more coal, especially at higher generator settings. If the player is using anything higher than level 1 for the generator’s setting, the player might be better off using installed heaters, unless the player needs to stack heating.

NO POINT USING RANGE EXTENDING OPTIONS:

The player can unlock the techs to extend the range of heating from the generator and steam hubs. Presumably, this may help the player reduce the amount of steam hubs that are needed. However, in practice, this is not worthwhile.

The main reason for this is that range-extension multiplies the coal consumption of the generators and steam hubs. This is a lot, and may be too high a price for the ease of having greater heating coverage.

Unfortunately, the player has to unlock the tech for extending the range of steam hubs in order to get the tech for improving their heating efficiency. Unlocking the range-extension tech causes the visual indicator for the range of a steam hub that would be placed to default to that of the extended range. There is no way to change the visual indicator for the heating range.

NO STACKED HEATING FROM OVERLAPPING RANGES:

The player can have steam hubs overlap each other’s heating coverage and the generator’s, but this is only good for purposes of redundancy. This is because the effects from the overlapped heating do not stack.

CAMPAIGNS:

Campaigns are the framework for all playthroughs. Although the game has introduced “Endless” modes since its release, the custom-sculpted campaigns are the main draw of the game. The main reason is that they have narratives, and another reason is that some of them has unique elements of gameplay.

However, in addition to careful resource management, all of them has one thing in common: a finale that hammers home the theme of desperation. Even the most meticulous player who habitually reloads game-saves would be astounded by the terrible – albeit short – conditions and dilemmas that the game would throw the player’s way just before the end.

The “New Home” campaign is the main one; the player is responsible for the largest group of refugees to come from this game’s steampunk Britain. Their site also happens to be among the most prepared, peculiarly circular as it is and well underneath the layer of ice that covers the Frostlands. If the player is skilled, the player would eventually save and keep safe hundreds of survivors.

It should be mentioned here that the player has to reach Day 20 of any “New Home” campaign in order to unlock the others. This is just as well, because the others are even less forgiving.

The “Arks” campaign has the player handling a few dozen engineers but little else, in order to keep certain buildings (that do practically nothing) warm. The lack of manpower is very noticeable in this one, and the player has to resort to fielding automatons to do most of the work.

Unfortunately, among the campaigns, this one highlights the bad pathfinding of people and automatons the most. It also highlights the design issues of task prioritization and lack of controls over the assignment of individuals to workplaces.

The “Refugees” campaign is an iffy campaign, since it has the most social commentary. It has plot elements that describe how British society was like prior to the coming of the cold. Resources are less of an issue and there would be no impending doom creeping up onto the player’s settlement. However, the player has to deal with the upheaval that would occur when refugees of different class strata converge on the player’s settlement, and there is baggage from drastic events prior to the fall of civilization too.

The “Fall of Winterhome” is closely tied to “New Home”, because it is a prequel to one of the turning points in that campaign. Where the other campaigns is about keeping people in and keeping them safe in the generator’s warmth, the settlement of Winterhome is doomed because its generator is failing. The player has to gather resources for people who are leaving so they can survive their escape. The player also has to manage the number of leaving people so that there is still some manpower left to support those who remain. Unlike the other campaigns, the player is guaranteed to lose. Rather, the player’s aim is to minimize the number of people who would die when the generator fails.

CREEPING WALL OF ICY DOOM:

This is a spoiler, but there are some campaigns where the player is notified of the “Great Storm”, which is practically an immense blizzard with unbelievably low temperatures. The Great Storm appears in the view of the Frostlands, and will render locations inaccessible as it creeps over by the hour. The exact extent of its current reach is not clearly indicated, however, so the player has to gauge this through seeing how many locations have been frozen over.

SOME OBTUSE CONDITIONS FOR TRIGGERING PROGESSION:

Conditions for progression in a narrative-driven playthrough are important factors for enjoyment. Frostpunk does mostly well in this regard, especially at how it tracks the fulfilment of objectives.

Unfortunately, there are some progression-related events whose triggers are unclear. Each campaign has at least one instance of this. Players who are anal-retentive about making optimal preparations will find these to be frustrating.

For example, the mid-game segment of a playthrough in “New Home” is about receiving waves of dozens of refugees. There is no warning when each wave might appear. Also, prior to this segment, there is a segment that can be triggered by either following the main objectives of the campaign, or triggered anyway after the player has been stalling for time; the latter is not told to the player, and can be an unpleasant surprise.

For another example, in the Arks campaign, there is the appearance of two regions with locations that can be explored for more resources. The triggering conditions are not informed to the player at all. Even at this time of writing, most third-party documentation either is not aware of this occurrence or is mistaken about the exact conditions.

That said, after having made many frustrating experiments, I discovered that the conditions are very specific (though relevant to one of the goals in this campaign). The player has to have a fully constructed coal mine, a sawmill and a steelworks, and has to have an automaton being constructed. Furthermore, when the automaton is fully constructed, the number of available steam cores must be 2 or less.

The game does not take into account Steam Cores that the player is trying to “bank” by placing buildings that need steam cores, such as the Factory, and pausing their construction. In other words, the steam cores must go into completely-made assets.

FREE-ENDED MAPS:

Some time after the launch of the game, maps for the “Endless Mode” were introduced. Some maps are relatively easy, being mainly there so that the player can try to unlock all techs and experience all gameplay content.

Some others are more desperate, starting the player off in locations with few resources and requiring the player to expand outwards away from the generator in order to secure resources.

VISUAL DESIGNS - OVERVIEW:

11-bit Studios had never been shy about using the latest graphics technology to display its games with. This is also the case for Frostpunk.

Being a game that is set in a frozen post-apocalypse, the player would not be seeing much other than snow and ice. The player may see soil and rocks peeking out from underneath the snow, but there are few other types of terrain.

The same can also be about the dead frozen trees; they are as dull as one would expect of dead frozen trees. The most that the game’s visual designers did for them is to implement transition models for when copses of trees are gradually cut down.

SNOW:

As to be expected of a game that is set in a stormy and wintery setting, there is a lot of snow billowing about. Their particle effects occur both close to the camera and near the ground. Indeed, there are occasions when the particle effects would glitch and the broken snow particles near the camera obscure the player’s view.

The best snow effects are those for the snow on the ground and the buildings. The snow on the buildings recede when the buildings warm up, and build up if they cool down; this is most noticeable for the arks in the Arks campaign. The snow parts as people move through it, and eventually re-accumulate in their wake. When automatons trudge across the snow, they leave behind holes that show their passing.

LIGHTING AND SHADOWING:

The most taxing parts of the graphics of Frostpunk are the lighting and shadowing. The people, the automatons and their buildings have a considerable number of light sources, such as the steampunk lanterns that just about everyone carries around and mount on their buildings. Everything in the game happens to cast shadows that reflect their shapes exactly; the generator, in particular, has a detailed shadow because of empty gaps in its structural design.

MODELS:

Like in This War of Mine, the camera is set far away and has limited zoom in Frostpunk. The player will never be able to see the faces of the humans, at least not clearly. Thus, this allowed 11-bit Studios to focus on the other things about the models of humans, namely their many-layered winter clothing.

Each type of building has several subtly different models. This can be seen best in the models of the shelters. The best variation is that for the flying hunters’ hangars. There are quite a number of different blimps that they use, and watching a fleet of them lift off during the night time can be entertaining.

All of the automatons look similar to each other, unfortunately. This is perhaps to be expected, since they are supposed to be standardized in design. Still, they do look quite impressive, especially when they deploy their legs from their boxy torso.

IMMENSE COMPUTING REQUIREMENTS:

The most entertaining and engaging part of the game is the final act of the main story, when so many survivors are crammed into the settlement awaiting an onslaught of lethal weather.

There will be a lot of particle effects from the weather. There would hundreds if not thousands of individual light sources that the player’s computer would struggle to produce. If the player has saved many people and sheltered them, there would be many, many polygons to maintain, sometimes even causing problems like model pop-ins.

The statement about the final act is admittedly a significant spoiler, but it should be mentioned here that this final act is far, far more taxing on the computer than the “recommended requirements” information of the game would suggest. If the player lacks a state-of-the-art computer, much of its excitement can be sapped due to the sagging framerates, or the watered down graphics after the player has lowered the graphical settings of the game.

As for the rest of the game, the game definitely needs more than the minimum requirements. Even at the lowest graphical setting, getting a decent frame rate can be difficult. The game attempts to mask this by giving everything sluggish animations (the extreme cold being a great excuse), but using time acceleration would reveal this visual trick.

CRASHES:

Unfortunately, sluggish performance would not be the only technical problems in the game.

The game loads all of its assets into access memory, so it uses incredible amounts of the latter. This also means that the game is vulnerable to memory leaks. Incidentally, a leak can happen after playing the game for several hours, and it is typically followed by a hard crash.

Another kind of crash can happen when the player is loading up the screen that shows the statistics for the settlement’s economy. It is unclear what triggers this crash, unfortunately.

WORST CRASH HAPPENS AT THE ENDING:

The most disappointing example of a crash is the one that happens right at the end of a campaign, whether the player’s settlement survived or not.

The ending is actually a time-compressed progression of the settlement from a bird’s-eye view; this data is included in the save-files (which can get quite large, as a consequence). The player is shown the appearance (or disappearance) of structures in the settlement, together with (likely) randomized placement of automatons and people in various poses.