The Road to E3: Multiplayer

We count down to the 2011 Electronic Entertainment Expo with a series of features about the issues affecting the future of the games industry.

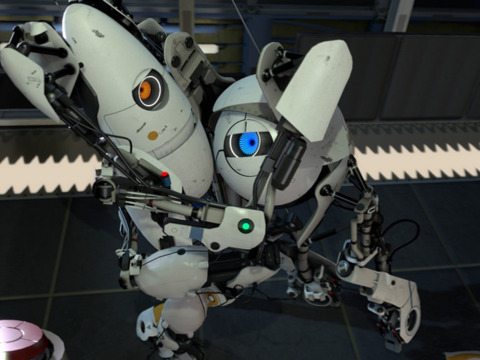

Multiplayer gaming has been an integral part of the wider gaming experience since the arcade days, taking on a new form with each passing decade and wave of technical innovation. In December last year, EA Games president Frank Gibeau declared that publishers can no longer get away with making games without a multiplayer component; indeed, Gibeau made it clear that games that fail to provide this all-important experience are likely to fail. This statement, bold as it was, echoed the thoughts of the wider industry. In an interview with Forbes magazine in June the same year, Square Enix head Yoichi Wada confirmed that every game that the company made from that point on would include some element of multiplayer or social gaming. Square Enix wasn't the only publisher eager to go down that road. In the past two years, the push toward multiplayer gaming has led publishers, developers, and consumers to rethink the way in which video games are both made and played. Ubisoft introduced multiplayer for the first time in its Assassin's Creed franchise; Valve launched co-op in Portal 2; Warner Brothers hinted at including multiplayer in future Batman games; and Sony has begun hiring programmers for what could be a multiplayer God of War game.

So where is multiplayer headed? Does it really stand true that games offering only single-player experiences are a thing of the past? Or are developers looking to create a more seamless experience between the two? To find out, GameSpot spoke to some of the biggest names in the industry today, including John Romero, Ubisoft's Patrick Redding, developers Harmonix and Activision's Call of Duty team.

Why We Play Together

When industry heavyweights like Frank Gibeau say that video games can no longer get away with offering just a single-player experience, they are also echoing the demands of the market. This ever-changing and ever-growing market is united by a common goal: entertainment. Video games, above all else, have to be fun. This is the reason why multiplayer not only makes sense as a gaming experience, but it's also the reason why more than one type of multiplayer experience has found success. People like to have fun with other people, whether it is in person or online.

But the benefits of playing together go far beyond making a great gaming experience. Nick Yee and Nic Ducheneaut are two researchers working as part of the Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) PlayOn project, which is focused on the study of social dynamics in multiplayer games. Using Web surveys, lab experiments, and data mining from games like World of Warcraft, Yee and Ducheneaut have looked at the social interactions between players, from examining players who fall in love online to what it means to be a guild leader. Analyzing the unique forms of social behavior that can happen in online games, Yee and Ducheneaut's research led them to discover that even though massively multiplayer online games are designed to encourage intense group interactions through raids and quests, it is more intimate sociability that keeps players interested in playing. This includes chatting with guild mates while grinding crafting materials, watching others perform fun tasks in the main cities, and the like. For some players, simply feeling part of a world inhabited by other human beings was enough. Based on their research, Yee and Ducheneaut have begun to develop tools to help game designers monitor social activity in online worlds.

With every game having its own sensibility when it comes to multiplayer, Yee and Ducheneaut have split the experience into three categories: a) games that are simply meant to be played with someone nearby, like Mario Kart; b) games that allow players to engage in a match-making system, like Halo or Call of Duty; and c) persistent virtual worlds, such as World of Warcraft.

"I want to be provocative and flip the question around and suggest that perhaps it is the games that are making relationships more salient and important," Yee says. "As a simple example of this concept, Farmville makes your friends more relevant and important because of the game mechanisms of gifting and helping. In the same way, World of Warcraft uses grouping and high-end raiding as a social means to satisfy game-related goals. Would playing games together be equally enjoyable if you could kill the dragon bosses by yourself? Certainly there are social players, but it’s equally important to keep in mind that game architecture also plays a crucial role in making people want to play with each other."

"I think playing games together simply makes your accomplishments in them more rewarding and more meaningful," Ducheneaut adds. "Nobody would care about wearing an epic set of armor if there were no one around to see it! Ted Castronova, a well-known game researcher, said that the presence of other people in online games validates emotions, and I think that’s exactly what’s going on: Doing something in the presence of other people who share the same interests and objectives makes it much more attractive."

This exhibitionist quality has also been observed by developers, who often focus test multiplayer experiences before a game's launch. Patrick Redding, game director at Ubisoft Toronto, is often amazed at how big of a role social skills play as a mechanism for negotiation in multiplayer games when he is observing focus tests. He believes game designers need to give players more autonomy in multiplayer, requiring them to use individual social skills to form a collective agency (in the case of co-op) and effectively overcome challenges. For example, observing player behavior in Splinter Cell: Conviction multiplayer, Redding found that players realized quickly that they have a better chance of beating the game if they work together. In this way, players working together are more likely to take risks and try things that they wouldn't have tried if they were playing single-player.

"Prior to recent years, the attitude was that single-player was different from multiplayer, and in fact, there was an implicit distinction between people who liked single-player (solitary, time-intensive) and people who liked multiplayer (mechanics-focused, living in the dynamics, doesn't care about the fiction of the game)," Redding says. "What's happened now is we've arrived at a new generation of players who want complexity and depth in both single-player and multiplayer. It has become socially acceptable to want this."

Are You Online?

There is certainly a feeling of going around in circles when it comes to multiplayer gaming. Video games were born as social experiences in the game arcades of the 1970s, gradually moving inside the home with the Atari 2600 and the Nintendo 64 and into split-screen territory on the Xbox and the PlayStation. Now, they've moved into the online space with the new-generation home consoles. While the Wii succeeded in bringing multiplayer back into the shared physical space of the living room, online multiplayer experiences still command a large portion of the market today.

According to the NPD Group--an industry research firm that has been tracking retail sales data in the US market since 1995-- the number-one best-selling title by units sold in US history, with 13.7 million units and total revenue of US$787.4 million to date, is Call of Duty: Black Ops. In March this year, NPD released a list of the all-time top 10 titles according to revenue (not units sold). While it's not correct to say that every single game on the list offers more in the way of a multiplayer experience than it does single-player, there is certainly a noticeable emphasis on games that offer a strong online multiplayer component: 1. Guitar Hero III: Legends of Rock; 2. Call of Duty: Black Ops; 3. Wii Fit; 4. Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2; 5. Rock Band; 6. Wii Play; 7. Guitar Hero World Tour; 8. Wii Fit Plus; 9. Mario Kart Wii; and 10. Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare.

Veteran game designer John Romero (cofounder of id Software and designer on Doom, Quake, and Wolfenstein 3D) was part of the development team that pioneered the modern concept of networked multiplayer with the release of Doom in 1993. The game was influential on many counts: It mass-popularized the first-person shooter genre and introduced cooperative and deathmatch modes (the latter term is also credited to Romero). Looking back, Romero admits the team set itself a lot of lofty technical goals with the game but not all of them were met.

"We issued a press release in January 1993 that said multiplayer was going to be in the game," he says. "Near the end of the project, we remembered that we said [that], and we hurried to start getting that working. At that time, IPX and TCP networking on a LAN was becoming common, and we had been using a company LAN for about two years at that point. So, learning the IPX protocol and how to transfer packets got us to moving the player around, and voila: multiplayer at a high rate of speed!"

Echoing Redding's thoughts on allowing players autonomy, Romero says the Doom team knew from the very start that it was important for players to feel in control: The more players can do in the world, the more immersed in the world they become.

"What I wanted the player to get out of it was a superfast shotgun blast to the face and really feel it. I wanted to be able to sneak around in a level and hunt down other players and surprise them with a rocket in the back. I wanted multiplayer to be everything I dreamed it could be, and it was at the time."

While games like Doom set the precedent for online multiplayer, franchises like Call of Duty have helped bring the experience to the mass market. The growing popularity of these titles points to a never-before-seen demand for experiences that bring people together in the online space. Treyarch design director on Call of Duty: Black Ops, David Vonderhaar, says it took the industry a long time to reach a point where multiplayer was taken seriously.

"In the earliest days of my professional career, having anyone devoted to multiplayer full time was rare, and more than two was something of a miracle," he says. "I consider myself very lucky to have watched this tiny and nearly immeasurable aspect of the game where perhaps 20,000 people might have had the technical capability to actually play multiplayer evolve into million-plus gamers. Online games have certainly gotten more sophisticated over the years, but I generally believe the experience has grown right alongside."

Vonderhaar has been with Activision for the majority of his 14-year professional career, working in central studio, production, and design management roles. His most recent task saw him focusing nearly exclusively on the multiplayer aspects of the Call of Duty franchise. This includes games like Call of Duty 3, Call of Duty: World at War, and Call of Duty: Black Ops. He says services like Xbox Live and consumer adoption of connected devices and open-development platforms like Facebook have grown and evolved the multiplayer experience throughout the decades.

"Fundamentally, multiplayer is so important to AAA titles because it adds so much value to the gaming experience. I'm personally fascinated in what these [the Wii, Move, and Kinect] and other controller-based games like DJ Hero, have done for multiplayer. Gathering together with others in front of the TV to play together or against one another, however indirectly, is great for the social experience. Capturing the vibe, emotion, and feeling of connectedness is something we'll be looking at for a long time. These technologies, and others to come, will help."

Call of Duty and the increased popularity of online multiplayer gaming also gave other multiplayer experiences a chance in the market. Although rhythm games have been a much-loved source of amusement in video game arcades all over Japan since the 1990s, the genre didn't become popular in the West until 2005 with the arrival of the first Guitar Hero game. Publisher Red Octane knew it was a risk--Western gamers simply didn't buy products that came packaged with several peripherals and cost almost triple the price of other games. (Charles Huang, the cofounder of Red Octane, had to take out a second mortgage on his house to raise enough money to get the game to market.) But by December 2005, Guitar Hero had become one of the hardest games to find at US retailers: Demand was huge, and Red Octane hadn't built enough peripherals. Five months after its release, the game cracked the top 10 best-selling games list, a position it held until the launch of Guitar Hero II.

"There were two things very unique about Guitar Hero when it was first released: The first was its social aspect," Huang told GameSpot in 2008. "This was before the term 'social gaming' had even been floated around, so this was just a game that was a lot of fun. Companies told us that people were reserving meeting rooms just so they could play Guitar Hero the entire day, and friends were saying that they were getting together on Saturday nights to play it."

The same thoughts echoed in the mind of Harmonix, the developers behind Guitar Hero I and II, and later, the Rock Band franchise. Although Harmonix recently laid off a number of its staff and has yet to outline its plans for the future, Harmonix designer Sylvain Dubrofsky (Rock Band 2, Rock Band Unplugged, The Beatles: Rock Band, and Rock Band 3) believes there are many success stories tied to the evolution of the multiplayer experience; something that points to how much this particular aspect of gaming has evolved.

"You've got synchronous versus asynchronous or same room versus networked or competitive versus cooperative: There are so many different game genres and systems on which to play that it makes sense that we see a wide variety of approaches," Dubrofsky says. "I think multiplayer experiences have grown primarily in terms of how much focus development teams are putting toward them, which results in deeper and more long-lasting experiences. Rhythm games are a natural fit. It's a performance simulation, and people like to perform together. Rock Band became this party phenomenon, and suddenly, your mom wanted to play video games with you."

Coming Full Circle

During the 2006 Electronic Entertainment Expo, Nintendo unveiled its plans for world domination: a new gaming system--originally known as the Revolution and later renamed the Wii--which promised to change gaming forever. The only problem was that nobody knew exactly how it planned to do this.

"[The] Wii will break down that wall that separates game players from everybody else," Nintendo said during the console's official launch. "[It] will put people more in touch with their games and with each other."

The industry wasn't convinced: How would it be possible to play immersive, in-depth games by waving a controller around in front of the TV? How would it be possible to play shooters and platformers? How was this console going to speak to the non-gamer? Nintendo insisted initial hesitations about motion-control gaming would dissipate. In an interview with CNET in January 2006, Nintendo of America president Reggie Fils-Aime proudly declared that Nintendo's aim was to "turn game development into a democracy of great ideas."

"The mythical performance vector for this industry is more processing power and prettier pictures, but what's really driven growth is actually improving the way consumers play and get into the game. It's what we've successfully done with the Nintendo DS and what we're committed to doing with the Revolution and the controller we've unveiled for [the] Revolution. That level of immersion really has never been done before."

Although Fils-Aime knew what the Wii could do, he could not have anticipated the effect the console would go on to have on the wider industry. By transforming the very nature of gameplay, the Wii successfully resurrected the idea of playing together in a shared physical space. Miyamoto's dream had come true: Gaming had once again broken free of the confines of the screen. Yet despite the Wii's success in carving out a new, casual gaming audience, there are some in the industry who believe that a multiplayer experience outside of the online space will not last long.

John Romero recently left his job to start a new social game development studio called Loot Drop. For him, looking at how multiplayer gaming has evolved on social networks is more important than "hopping and jumping" around to the Wii, Move, or Kinect.

"The asynchronous nature of gameplay in social games is very different from what hardcore gamers are used to, and pushing the boundaries of asynchronous design, before it becomes synchronous, is presenting some interesting gameplay," Romero says. "The Wii, Kinect, and Move are simply controller-replacement technologies. It's up to game designers to use them for multiplayer games. I personally feel that the Kinect and Move are fads that will die just like 3D TV is dying. The reason is that the majority of players just don't want to be hopping and jumping around in their living rooms. I want a minimum amount of effort for a maximum amount of gameplay. That has always been the case in controller design, and the Kinect and Move go against that doctrine."

Romero now believes that the industry has, for the most part, kept multiplayer gaming confined to what can be loaded into a level. For this reason, experiences like World of Warcraft are rare. Players can play in an entire world without loading screens and interact with other players in a big space. He says the future of multiplayer lies in the online space, not in the physical space currently dominated by publishers like Nintendo.

"The industry needs to push much harder to develop full streaming technologies to take multiplayer to the next level. The future of large multiplayer games is all about streaming worlds. With casual games, it's still about competing in a very simple manner if you're in the living room together and jacking around in front of the TV with a Wii Remote, Move or Kinect."

Harmonix's Sylvain Dubrofsky also sees multiplayer heading toward a more social online space, where games will make it easier for players to find and make friends. This is something currently being looked at in the rhythm game genre, which Dubrofsky says is far from spent, despite Activision's recent announcement that the publisher's Guitar Hero unit has been temporarily disbanded.

"Multiplayer really plays to the strengths of games as a medium to provide unique experiences that are not 100 percent authored by the development teams. We’ve said for a while that what the music-game genre needs is innovation, and we are committed to exploring new types of music gaming, both within our established franchises and outside of them. It is important to note that [Harmonix] has never viewed performance simulators, such as Rock Band, as the only possible type of music game. We think there are a variety of music game ideas worth exploring, and we are hard at work right now exploring them."

But despite what audiences seem to want, some developers aren't convinced that single-player experiences are on the way out. It's not hard to recognize when multiplayer has been hastily tacked on to the end of a game or when a particular game works much better as a single-player experience than a multiplayer one. Treyarch's Vonderhaar says there is plenty of room for high-quality, innovative games that don't have any multiplayer whatsoever.

"As a hardcore online gamer who has been advocating that publishers and developers invest heavily in multiplayer his entire professional career, I genuinely want to agree with this [Frank Gibeau's statement that publishers can no longer get away with making games without a multiplayer component]," Vonderhaar says. "However, I don't agree. I love multiplayer more than anything, but forcing it into every game isn't the right thing to do and won't work. It's not a component that can be tacked on to what is otherwise a thoughtful and well-designed single-player experience."

Both Vonderhaar and Ubisoft's Redding believe that rather than try to force a multiplayer component into a game that clearly does not need it, the future lies in creating a more seamless experience for the player. This would be one that blurs the line between traditional concepts of single-player and multiplayer, which is something that MMOGs like World of Warcraft have been doing successfully for years.

"There's more recognition now that players are not disorientated by the experience of hopping in and out of game," Redding says. "The social presence we have now in games with things like Facebook and Twitter integration means that one day, more games will allow players to move dynamically between the different gameplay modes without things like menus getting in the way. It's better for us as developers to try to embrace this trend. Cross-pollination is inevitable and will allow us to tap into a level of comfort that most players are used to by now. We should open the gates and let players play with the technologies that they want."

Got a news tip or want to contact us directly? Email news@gamespot.com

Join the conversation