Yakuza is a high-concept game that achieves its goals, but only if one is willing to take the time to enjoy the ride.

None of this could be further from the truth.

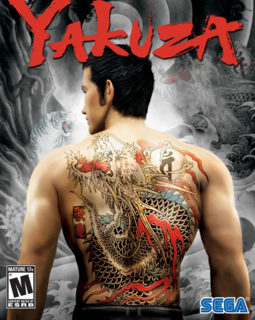

Whether intentional or not, sitting down and getting into Yakuza plays out like a metaphorical journey into Tokyo's seedy underworld itself, where nothing is as it appears and hidden agendas and intriguing secrets are abound. Yakuza opens with Kazuma Kiryu (who pulls through with the action game genre prerequisites of being the kindest-hearted, biggest badass in his dark profession) on a quick run to collect an unpaid debt. This debt collection run introduces the brawling system, the meat-and-bones of Yakuza. The combat controls feels a little sloppy (which it admittedly is), but it eventually proves itself to also be a surprisingly adaptable system, especially as Kazuma upgrades his stats and learns new abilities through the game's leveling-up system. Immediately after this expository mission, a quick and unpleasant turn of fate pits Kazuma against longtime friends and locks him in the slammer for a decade. Flashing forward ten years to Kazuma's release from incarceration, the game unleashes its "world map" (Tokyo's Shinjuku Ward's infamous Kabukicho red-light district, referred to in-game as Kamurocho), and Kazuma's journey opens up to a wealth of sidequests and minigames, which include Bacarrat and slots, working street connections to enter hidden weapons shops, raising your trust with a little girl by indulging her desires for desserts, underground fighting tournaments, and dating simulations. Though Yakuza is by core and design a brawler, its extensive representation of Shinjuku and the darker side of Japan's downtown entertainment turn the world of Yakuza into an experience closer in spirit to that of an adventure title like the Legend of Zelda series (indulging in the avaliable sidequests easily inflates gameplay time beyond the 20-hour mark).

The storytelling in Yakuza is episodic in nature, with a lot of faces and names coming and going between chapters, some to turn up again later as either essential parts of the story or as optional sidequests, while others with their storylines resolved within individual chapters. While not immediately evident, the meandering plot of Yakuza eventually pulls into high gear as the game turns into its third act, and through a series of plot revelations the story ultimately reveals itself to have been guided by the hand of a talented writer, serving well the Hollywood adage of "the same but different," throwing cliche situations at the player with them sufficent color and context as so that they stand on their own, and in the end deliver a memorable experience.

Yakuza has apparently undergone extensive localization before its release on North American soil. The voice cast is solid (the cast is fleshed out with names including Michael Masden, Eliza Dushku, Rachael Leigh Cook, and Mark Hamill), but it's sometimes apparent that actors weren't recording their lines in the same studio, and occasionally the delivery of their very lines has been altered with noticable omissions or additions of silence between words. The pronounceation of Japanese names and jargon is all over the board, the most notable being the colorful and varied butchering of poor Kazuma Kiryu's name (though nobody ever delivers the classic English-language disgrace by saying "Ya'Kooo-Zuh"). The game somewhat ironically suffers from its superb (Japanese-language) lip-synching, and the dialogue very often is noticably at a mismatch, though the observant gamer that knows some Japanese will be able to discern some of the original dialogue verbatim - the lip-synch is that good. The pachinko parlor has been converted to generic "slots" for North America (as if pachinko wasn't famous enough?), and some of the street thugs seems to have been rebuilt to match a generic G-Unit inspired fashion style, wearing large plain sports jerseys and bandanas over their faces. This is an area of the localization that could potentially be considered offensive; the street thugs banter is often delivered in a heavy "ebonics" delivery, and a fair number of the homeless character models have skin much darker than one would expect from Japanese characters - a change likely made to make the homeless characters "read more realistically" to Americans, and what this implies about our society is troubling indeed. However, it remains a small factor of the game, though it never stops sticking out as odd.

As a Japanese-developed title, Yakuza sometimes skimps on explanations of the Japanese social institutions that fill the game, and those familiar with actual Japanese urban life will likely get a very different experience out of Yakuza than those who are not. However, any gamer with an open mind towards both the subject matter and the game itself should find a solid and recommendable experience hidden deep in this adventure in Tokyo's underworld.

Yakuza is a title that should be viewed as an adventure title or perhaps even a light RPG, and if approached as such, it's a game with a great potential to deliver a memorable experience. Yakuza is ultimately a high-concept game that achieves its goals, but only if one is willing to take the time to enjoy the ride.