INTRO:

Tabletop games can be incredibly cheap, if the players and their game master can agree on just using their imagination for visualizing the narrative. However, in terms of gameplay, they will have to use simplified and/or abstracted rules in order to compensate for their lack of any physical aid.

If the game has rules that involve measurements, character placements and other physical factors, gameplay experiences and affordability can vary tremendously. It can be incredibly expensive, if the players insist on models and other sculpted objects. It can be incredibly silly and dissatisfying, if the players have to use cheap substitutes like toilet rolls in place of models.

Ironically, the digital platform can address a lot of the issues with table-top games. The digital version of The Warlock of Firetop Mountain is an example.

YOU ARE ALONE:

The original The Warlock of Firetop Mountain has the appeal of being a completely single-player game. There are no parties, so there is no intra-party drama, divvying of loot, assigning of tasks and other hassles and trouble that one would expect from a group of motley adventurers trying to work with each other.

Of course, the main trade-off is that the player character can only depend on his/her own capabilities, and any shortfalls will not be compensated for. Obviously, if the player character dies, he/she dies alone and miserably.

PREMISE:

The digital version of the game does not deviate from the original story. The eponymous Warlock of Firetop Mountain is a notorious villain, having seized controlled of the region around the mountain with his incredibly sorcery. He has many monsters and other inhuman things within his domain, some of which are his minions while many others are taking advantage of the environments that he has made.

Although there is civilization just outside the mountain, the people live in constant fear of the warlock and the predations of the foul things that live in the shadow of his home.

Such a villain and villainous stronghold filled with lesser villains attract a lot of would-be righteous heroes, curious vagabonds or greedy treasure hunters. This is just as well to Zagor, the titular Warlock; their strong souls are worth much to the likes of him and they, ironically, happen to have gear and items that are treasures in themselves. His demesne is indeed dangerous enough to kill the protagonists – or so he would think.

ORIANA:

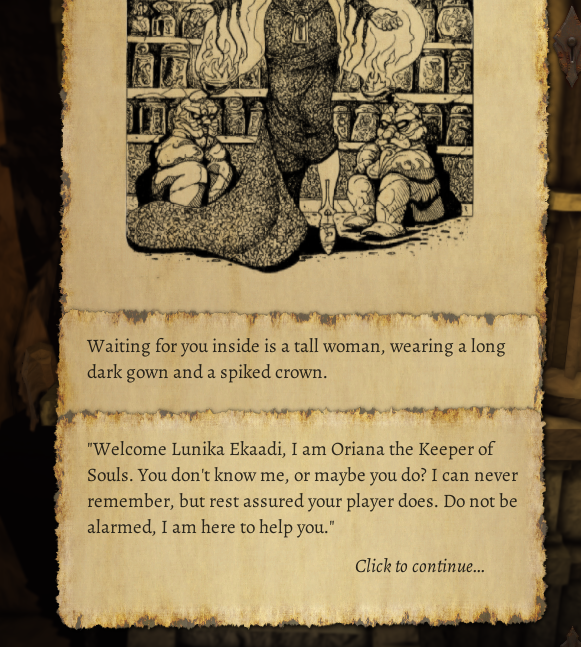

Oriana is a seemingly omniscient being that is capable of seeing past the fourth wall; she is well aware of the player’s involvement, and how the player would be directing the protagonists like unwitting game pieces. She does actually say this out loud in front of the protagonists, thus bewildering them (or alarming them, in the case of those who are aware of the existence of omniscient entities).

Anyway, Oriana is the player’s guide, and apparently game master too. She may appear from time to time to inform the player about gameplay mechanisms, or to reward the player for some impressive feat. She also appears at one location in the actual game, acting as a shopkeeper who would, for whatever reason, accept the player character’s coinage.

Oriana is also an unlockable character that is usable for the “Goblin Gauntlet” game mode, which will be described later.

DICE ROLLS:

As to be expected of a game based on a table-top IP, there are dice rolls involved. The dice used are standard D6’s, and there are usually two of them.

These two are placed into an on-screen bowl (of sorts); the player can see them tumbling around as they clack into each other and rebound off the edges of the bowl. This is not just for aesthetic purposes; the outcome of the roll will depend on this clacking around. Indeed, the physics of the rolling can put noticeable strain on the computer’s graphics processing.

POKING THE DICE:

Of course, if the player can do nothing, the rolling of the dice might as well be fickle and uncontrollable as an RNG roll. That said, the player can actually do something – namely poking the dice.

Unlike the dice poking in Tharsis (another game with dice rolls), the dice poking in this game imparts considerable momentum. Indeed, the player could keep poking the dice and have them clacking about indefinitely. The confines of the bowl make it easier to do so.

Of course, the player would eventually have to let the dice settle in order to proceed – preferably when the dice would seem to settle with favourable faces.

ROLLS AGAINST STATISTICS:

The player character has three statistics. There will be dice rolls against two of these statistics in many non-combat but otherwise significant situations. For success, the dice must yield a total value equal or under the numbers for the statistics.

Incidentally, most statistics that would be rolled against would be 10 or lower, in order to have a real and significant chance of failure. Most statistics would be higher than 7 too, mainly because a total value of 7 has the greatest portion of possible outcomes from the dice rolls.

SKILL:

The main statistic is perhaps Skill, mainly because it is used in many situations outside of combat, and is used during combat too.

Some non-combat situations require rolls against Skill; typically, this involves their finesse. These situations also include any tests of agility, though some characters have traits that make such rolls unnecessary. Skill is also used in “clash” contests during combat, whenever they happen. These will be described later.

LUCK:

Luck is the statistic that is sometimes used to give the player character a chance of sorts when things that are out of the player’s control happens. Not all uncontrollable situations would use Luck, however.

When the player does get this chance, a pair of dice would be rolled against the player character’s Luck rating; this is not unlike situations that involve rolls against Skill. As with Skill, the outcome has to be equal or under the Luck rating for the roll to be successful.

Luck is generally not used in combat. However, there are some rare few characters that do use the rating in some of their attacks or moves. Still, Luck is mostly used outside of combat, meaning that it is quite wasted in the Gauntlet mode (more on this later).

LUCK AND SKILL DRAIN & RESTORATION:

Luck and Skill generally stay the same. However, they are represented as fractional counters for a reason; there are occasions when Luck and Skill can be drained, and the denominators act as reminders of the original amounts.

Skill drains usually happen when the player character gets into an embarrassing situation that saps their confidence. Luck drains happen when the player character gets into situations involving superstitions about luck and messes up.

Luck and Skill can be restored through the opposite sort of events. Situations that improve the confidence of the player character restore Skill, whereas fortuitous occasions (like finding a clover plant with more than four leaves) restore Luck. Luck and Skill can never be raised beyond their maximum, by the way.

STAMINA:

Stamina is the hit points of the player character. Stamina is lost when the player character sustains injuries, or has a bout of severe exhaustion. This can happen through mishaps outside of combat, unsuccessful attempts at dodging dangers and, of course, taking hits during combat.

There are rarely any rolls against Stamina, but there are sometimes checks on Stamina, meaning that things get exponentially worse as the player character’s Stamina lowers.

Fortunately, Stamina is more readily restored than Luck or Skill. At any time, even during scenarios, the player can open the inventory screen and have the player character scarf down something to restore Stamina. That said, the player character is that kind of video game protagonist that can heal through eating food.

There are also things other than food that can restore Stamina. There is the Potion of Strength, which is practically a potion of healing (rather than the usual typical potion that gives a strength buff).

PLAYER CHARACTER TRAITS:

Any player character has gameplay-affecting traits. These are usually only useful in non-combat situations. For example, traits about the player character’s alacrity lets him/her dodge incoming hazards, like a boulder from a boulder trap.

Perhaps the most important of these traits is “Educated”. This means that the player character can read. It so happens that Firetop Mountain has things like signage, books and scrolls, all of which impart important information that the Educated understand quite readily. Those who are uneducated might have a hard time, especially if the player is using them for the first-ever run.

INVENTORY:

Like any other self-respecting adventurer, the player character has stowage somewhere on his/her person to stuff things into. There is no limit to the number of items that the player character can have, as long as the items are sufficiently small.

The items are split into two overarching categories: consumables and non-consumables. Consumables are things that the player character identifies as being immediately useful, like provisions and potions.

In the case of consumables that can restore Stamina, the player can open the inventory at any time to use them. Doing this will be quite important, especially if the player has more than enough provisions or potions of strength.

Non-consumables are often artifacts, keys, tools or some other objects with uses that are not immediately apparent. Generally, the player would want to have as many of them as possible so that the player is prepared for any situation that can be resolved with the use of one of these items. However, the presence of certain items in the inventory might complicate things, such as in the case of covetous entities that can detect the presence of powerful artifacts in the player’s possession.

RESTING BENCHES:

Curiously, there are benches strewn throughout the demesne of Firetop Mountain, even though none of its denizens would be able to use them, want to use them, or even acknowledge their presence. Oriana describes them as being places where any player character can rest without being disturbed. That said, any adventurer would somehow recognize this as a safe spot. (There is some dry humour from the adventurers wondering why these are around and why they are somehow safe spots.)

Resting at these places restores some Stamina points. If the player character consumes a unit of provisions before doing so, more points are restored; the amounts are greater than that from both manual provision consumption and regular resting combined. Anal-retentive players who knows when and where to expect these places may withhold consumption of provisions so that they can be efficiently consumed at these places.

CHECKPOINTS:

The resting benches also happen to be checkpoints; the player can confirm this by looking at the save-game files. For a reason that Oriana would explain with her omniscient powers, the player character’s progress through Firetop Mountain is recorded at the bench that he/she most recently rested at.

The player character also has “Resurrection Stones” in his/her possession; he/she acknowledges that these are somehow important, but does not know what they do. However, Oriana does, and she would explain that these represent “extra lives”. Any time that the player character is slain, one of the stones are expended, and the game would reset to the most recent resting bench.

If the player has not been thorough in finding the resting benches, this might mean a lot of lost progress. Of course, if it was the player’s first run, the player would now have the advantage of knowing what lies ahead, even if the player character does not. (The player character rarely if not never experiences any sense of déjà vu, by the way.)

If all stones have been expended, the playthrough is lost and the player would be reminded that this game is a rogue-lite.

SAVE-SCUMMING:

Of course, the player could just resort to save-scumming to avoid spending any stones, or lose any progress for that matter.

The game auto-saves after just about every input that the player does. Therefore, the player could make a game-save back-up just before a decision, and revert to that back-up if a decision turns out awry. There does not appear to be any randomization in the outcomes of the decisions too, thus making save-scumming a sure way to win the first playthrough.

The auto-save will not update during combat. This means that the player could possibly exit out of a fight and resume the playthrough just to try the fight again.

CERTAIN DEATH OUTCOMES:

Having described save-scumming, the least pleasant design of the gameplay would be described next. This is the inclusion of scenarios with options that lead to fatal outcomes.

Most scenarios would not give options that are undoubtedly suicidal, like ingesting poison. However, there are scenarios where the player is given options that are terribly unwise, and which would turn out to be exactly that if the player picks them. A recurring example is crawling into spaces that are practically the warrens of poisonous spiders.

However, there are options with fatal outcomes that are not easily predictable. Some might impart some warning of sorts, such as a puzzle room that happens to have splotches of dried blood here and there.

Some others prey on players’ tendency towards diplomatic solutions, such as trying to reason with already-angry sentient individuals, only to let them make hits on the player character while his/her guard is down. Of course, the punishment for these is not outright death, but damage will be dealt and if the player character is already weakened, death might happen.

Fortunately, there are not too many of these scenarios.

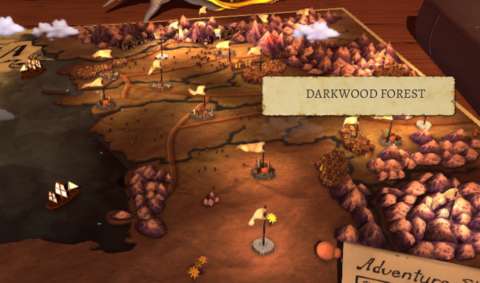

DIORAMAS:

The game’s visual presentation utilizes dioramas. Every major section of the playthrough is represented with a set of models representing the environs, which are also populated with figurines that represent the characters that live in them.

Most of the sets have cut-away sections that are lifted out of sight to show what is underneath them. This is not always the case, such as one segment in an underground port in which the insides of a dockyard and a hut are not shown.

At first, only one set is shown; this is the starting location of the section. Venturing further adds another set to the first one, and so on and so forth until there are many sets joined together.

Unfortunately, the player is not given the choice of zooming the camera out to the see the arrangement of the sets in their full glory. This is a wasted opportunity for the developers to show how much effort that they have put into making the game.

On the other hand, considering how much computing resources that the game would eventually consume – and the likelihood that earlier out-of-sight sets may have been removed – this is probably a wise design decision, albeit not an ideal one.

COMBAT - OVERVIEW:

The player may come across circumstances where combat can be avoided, or not. In the case of the latter, or if the player chooses to fight anyway, the player is thrown into what passes as fights in this game.

Each combat segment has been crafted for the occasion and locale in which it occurs. Thus, the player should not expect procedural generation or a stock-standard battlefield. However, the different sets have certain similarities.

Firstly, all of them occur in a limited span of area. None of the characters can move out of this area, and there can only be so much space for them to move about in. Some fights might have more enemies spawning in, but no one would leave except as casualties or as the victor.

Speaking of which, a fight only ends when the player character is dead, or everyone else is dead. The latter can be a daunting outcomes at times, because the player character can be outnumbered as many as one to eight.

Even if the odds are better, the few enemies might be statistically more powerful than the player character, and may have more hit points too.

TURNS:

Combat plays out in turns; the controllers of the characters decide on the actions that they would make. When the player ends the turn, the actions are effected. The outcomes and the order in which they are resolved are determined through some rules that will be described later.

In the case of enemies, the CPU decides the moves for them according to the behaviour scripts that are associated with them. These behaviours will be described later. However, these scripts have one thing in common: enemies will never do nothing in their turns.

Likewise, the player must either have the player character move to another square or make an attack (or make an attack that makes the player character move). The player cannot choose to have the player character do nothing, for better or worse.

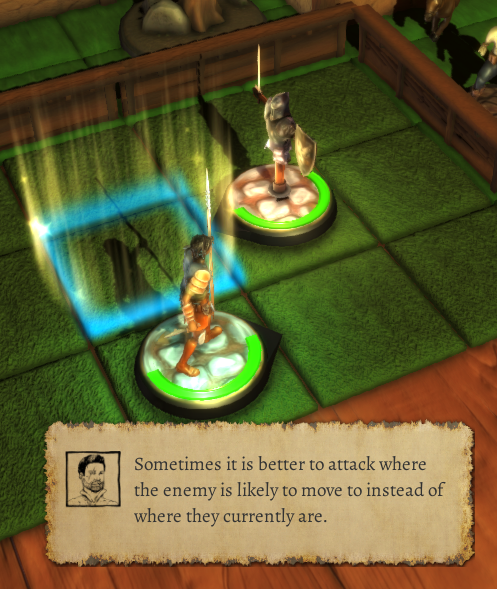

BATTLEFIELD GRID:

Combat plays out on a grid of squares. Each character either occupies one square, or a bigger square comprised of multiple squares in the case of large opponents. Some squares may be occupied with obstacles like tables and chairs.

Some obstacles can be destroyed with attacks, while some others are invulnerable. In the case of destructible objects, the player may hear sounds of things being damaged, like steel striking wood. Removing obstacles of course clears up the grid, which makes movement easier for both the player character and enemies. (Since there are more enemies than there is the player character, enemies benefit more from this.)

During the phase when the player decides what to have the player character do, the player can see the squares that the player character can move onto and the squares that he/she can make attacks on.

Colour-coding is used for differentiation: blue for squares that the player character can move onto and make attacks on, and orange-red for squares that the player character can make attacks on but not move onto. It takes a while to understand, mainly because the tutorial does not thoroughly explain the colour coding.

LIST OF ACTIONS ON A SQUARE:

Clicking on any viable square shows a list of possible actions that can be done on that square. This seems par for the course – at least until the player notices that there is no “cancel” option.

In order to backtrack from the selection of a square, the player must click on another square. To completely cancel the selection of any square, the player has to click on squares that the player character cannot reach. This is not told to the player, unfortunately.

MAKING ATTACKS:

When the owner of a character chooses to make an attack on a square, he/she/it restarts the cooldown for that attack. Basic attacks – which usually do little damage and have little range – have no cooldowns; they are always available in any turn.

Attack actions are only performed after other characters have made their movement actions, if any. This is important to keep in mind, because the player character has to hit at where enemies are going instead of where they are, assuming that the player knows where they are going to move. Otherwise, the attack is wasted.

Similarly, this also applies to enemies. The player must know what kind of attacks that they would use next, however, in order to make effective dodges.

AREA-EFFECT ATTACKS:

Most player characters have at least one area-effect attack. Even the least of these is a wide slash, which can hit two squares. This is just as well, because the player character is almost always outnumbered.

There are enemies that can perform area attacks too. This can complicate dodging attempts. On the other hand, the area-effect attacks of some enemies can inflict damage on their compatriots, so a cunning player might be able to trick enemies into hitting each other.

“CLASH”:

If the player character and an enemy make attacks on each other within the same turn, a “clash” happens; the nature of their attacks does not matter. Anyway, each of them has to roll a pair of dice; the total value of the outcome is added to their Skill ratings. Their sums are then compared to each other; whoever has a higher sum wins the “clash”. The winner gets to apply his/her damage, whereas the loser has to take the hit, unless his/her attack comes with some defensive measures, in which case these will apply.

In the case of a draw, both characters waste their attacks. The player character can still be hit by another enemy, of course.

If the player character used an area effect attack and hit multiple enemies that also made attacks on him/her, the player has to resolve multiple “clash” roll-offs.

ENEMY BEHAVIOURS - OVERVIEW:

Although the enemies that the player character would fight are understandably hostile and will want him/her dead, they are not all competent at doing that.

Most enemies move about the grid in seemingly random directions. There may be some scripts that determine whether they move in the direction of the player character or in some other direction. If there are such scripts, then the RNG rolls are generally rigged against them.

If they are making an attack, they choose one of those that they have, if they have more than one type of attack. After making that attack, they usually go down their lists of attacks in later turns when they make attacks. This can make them seem like clockwork opponents, which was perhaps the intention of the developers.

If the player can observe and remember their attack patterns, the player can come with an attack pattern of his/her own to handily counter the enemy’s. Of course, if there are more enemies around, things get complicated rather quickly.

FACING & FORWARDS AND SIDEWAYS MOVEMENT:

Usually, enemies either move forward or sideways. Some enemies can do both, albeit alternating between them in every turn that they move. The facing of the figurines for enemies usually indicates which possible directions that they can move.

Some enemies are not mindful of obstacles in their way when they spend their turn to move. If they are not physically powerful monsters, they simply bump into these obstacles and waste their turns. Again, this can give the impression that they are clockwork enemies.

Such patterns of movement also mean that their rear facing is always vulnerable. Of course, the player will need to recognize which is their rear facing; there are enemies with physiology that is not immediately recognizable.

BEING MOBBED:

There are enemies that actively move to get closer to the player character. The player character runs the risk of being trapped if enough of these enemies surround him/her. This risk is greater if the player is using the edges of the grid to move about.

LARGE OPPONENTS:

As mentioned earlier, there are opponents that occupy spaces more than one square in size. These opponents tend to have considerable amounts of hit points, as befitting their size.

However, large opponents need to have enough space to move about. This is a major impediment that the player can exploit, if there are obstacles that prevent their movement. On the other hand, large opponents tend to be bulky enough such that they can crash through most obstacles. Furthermore, their large size lets them pin the player character to an edge of the grid rather easily.

GOBLIN GAUNTLET:

As its name suggests, the “Goblin Gauntlet” game mode is a gauntlet-style one: the player character is expected to get in fight after fight, and survive for as long as possible until the next resting point. There are no provisions to eat, and there are no other means of healing in between resting spots.

The Goblin Gauntlet was supposed to be a game mode that comes with the Goblin Scourge DLC. However, it was also included in the main game package – but with a caveat.

This caveat is that it is meant to be played with the characters that are unlocked by the Goblin Scourge DLC. If it has not been purchased and no other character has been unlocked, the game mode is not playable.

Thus far, the only playable character for Goblin Gauntlet is the unlockable Oriana the Soulkeeper, who is very much the avatar of Oriana. (The player should not expect dry wit from Oriana though; she does not seem to acknowledge that the player is using her figurine to play the gauntlet mode.) Of course, the code to unlock Oriana has long been deciphered by followers of Fighting Fantasy, so a mere search on the Internet would reveal it.

PLAYABLE ORIANA:

During the year after the game’s release, players have been teased about bits of code that would unlock Oriana as a playable character. These bits of code are actually references to pages in the original Fighting Fantasy books, so only long-time followers of the IP would have been able to decipher them.

Of course, everyone else could just copy-paste the deciphered code from the forum thread that tracked the progress of the deciphering. This unlocks Oriana’s seemingly masked avatar (so it is not entirely clear whether this is Oriana herself or not).

Anyway, Oriana’s avatar does not have very high stats, despite Oriana being a supernatural being. In fact, she is no more durable than a human, i.e. not having stats higher than most characters.

However, one of her attacks is a dice roll that inflicts damage equal to the value of the dice. Considering that the player can control the dice rolls, this is a potent attack indeed. Furthermore, if the player can manipulate the dice and produce an outcome of a double, the damage is duplicated and applied to all extant enemies. This is obviously a significant advantage.

SOULS:

Whenever the player character defeats enemies, he/she gains souls. There are also treasures in the form of souls trapped in gems. Beyond-mortal characters such as Oriana and Zagor do recognize the worth of these ‘resources’; Oriana, in particular, would dole them out as rewards. The player characters also somehow recognize them as valuable, despite how macabre they are.

Incidentally, souls as a resource was not exactly a known element in the setting of Fighting Fantasy. At most, they were used to highlight the wickedness of villains who harness stolen souls. Indeed, it seems to have been implemented in this game as one of the rogue-lite elements. Of course, there is the bit about From Software’s designers having mentioned that Fighting Fantasy were among their inspirations, so this could have been an homage to Dark Souls too.

Anyway, collected souls are added to the player’s tally after the end of a run, successful or otherwise. They are used to unlock more player characters, thus encouraging the player to have more runs but with different protagonists with different motivations.

PLAYER CHARACTER’S PERSONAL QUEST:

Speaking of which, each individual player character has a reason for entering Firetop Mountain. Usually, this involves their personal quest, which varies from character to character. Whatever this quest is, it falls under one of two categories: the retrieval of some artefact or, the elimination of a specific individual for whatever reason (usually justice or revenge). Some personal quests are a combination of both.

The fulfilment of these quests occur at various points in the playthrough, but rarely at the final act, which is the Warlock’s sanctum. The text narrative generally points out how close the player character is to achieving any objective.

Furthermore, the player’s choices in some scenarios are narrowed down, often to just one that would lead to pursuit of the quest. However, there are circumstances where the player character might not even fulfil his/her personal quest at all, even if he/she defeated the Warlock.

Speaking of which, interestingly, few of the quests directly involve the titular Warlock. Indeed, after their personal quest has been achieved, the player can choose to have them (somehow) leave Firetop Mountain.

If the player so chooses (likely because he/she has run out of Resurrection Stones or other consumables), the run ends. Consequently, the player forfeits any further rewards from forging onwards to defeat the Warlock. The player does get the reward for having completed their personal quest, however.

LITTLE ANIMATIONS:

Dioramas and other set-pieces fall into place with particle effects of dust and sand blowing up as they land. The models themselves are also quite intricate, especially those of the player characters.

However, there are little other visual designs. Outside of combat, only the player character’s figurine moves, and it simply merely turns on its base or hops around on it. In combat, the figurines merely rotate, slides forward or sideways, or shake when they are hit.

Of course, such visual designs are entirely intended by the developer Tin Man Games. If it is not apparent already, the game is intended to have the look of a table-top game with (very expensive) model sets.

On the other hand, Tin Man Games will not continue this design direction in its later games, namely Fighting Fantasy Classics.

UPDATED ARTWORK:

Some of the artwork in the original Fighting Fantasy book have been adapted and updated for the digital version of the game. This would be mainly recognizable to followers of that IP, of course.

SOUND DESIGNS:

Most of the sounds that the player would hear from the game are the music tracks. Speaking of which, most of them mesh well with the themes and setting of the game. Of course, that is a positive way of saying that it is the usual orchestral that typically permeates any work of fantastical fiction in an audio/video format.

That said, the purchase of the license for the game does not come with the packaging of the game’s soundtracks. Although this might not seem like a lost opportunity because most of the tracks would sound rather forgettable to a jaded player, there is one track that stands out. This is the track that plays when the player character comes into the training hall for the orcs.

(The developer would reveal in a Steam forum thread that the song has been sourced from Battlebards.com, though which track is unclear.)

There are not a lot of legible voice-overs in the game. There are vocals that are associated with enemies that play during combat, such as the snarling of canines during fights with the fantastical dog-like creatures of Fighting Fantasy. Yet, that is the most that the player would hear. None of the player characters have any voice-overs. Neither Oriana nor the titular Warlock has any voiced lines too.

During combat, the player will hear noises that accompany the particle effects that appear when characters make attacks. They are usually appropriate to whatever is making the attack, but not what is being hit. There is also the sound of ceramic sliding across ceramic that the figurines make when they move.

Perhaps the best sound designs in the game are the background noises. They provide appropriate ambience to the environments that the player character would come across. For example, caverns have the hollow sighs of air moving through the tunnels, and if they happen to be inhabited by fantastical spiders, the player may be able to hear their chittering. (Real spiders do not chitter of course.)

NO FURTHER CONTENT UPDATE:

At this time, further development of content for the digital version of The Warlock of Firetop Mountain has been put into stasis. Apparently, Tin Man Games has shifted its focus to Fighting Fantasy Classics, a mostly text-based game that would be easier for the developer to deliver.

SUMMARY:

Followers of the decades-old Fighting Fantasy might find the digital version of Warlock of Firetop Mountain to be an entertaining adaptation of the first book in the series. The 3D models for the environs and figurines may be even more entertaining, especially to people who remember but could not afford the real models when they were made way back when.

For everyone else, the fourth-wall elements in the story-telling can be amusing. It might break immersion, but then, having static figurines hop around stiff-looking environs already does that.

The combat is perhaps where most of the sophistication in the game lies. The clockwork-like enemies can seem silly at first, but defeating them with shrewd planning and guesswork can be fun. Incidentally, the Goblin Gauntlet mode is all about doing so.

The player should not expect any further content updates for the game, however, due to the aforementioned development shift to Fighting Fantasy Classics.