INTRO:

During the early days of Sierra’s foray into point-and-click adventure games, there were a lot of memorable titles; it so happens that these often have inane and comical humour. Success (at least success in popularity, if not commercially) meant that there would be a considerable number of me-toos.

Teenagent (named as Teen Agent in GameSpot’s archives) is one such me-too. It tries to replicate the funniness of its sources of inspiration. Yet, there were a considerable number of missteps which greatly detracted from its fun.

PREMISE:

Banks are having their vaults emptied before the very eyes of their guards. The task to solve this has been handed to the RGB agency (obviously a double-reference to the latest in computer graphics at the time and the Cold-War-era Russian intelligence agency). However, the RGB too is stumped.

In desperation, the RGB has resorted to hiring a fortune teller to provide them with a solution. The fortune teller pointed out an individual, seemingly at random. This is of course the protagonist, and against their better judgement, the RGB would recruit this teenage boy to its cause.

The protagonist is Mark, the teenager who would turn into the titular “Teen Agent”. He does not have much ambition, as is typical of a teenager, but it was easy for the RGB to take advantage of his juvenile inclinations.

PLAYER CHARACTER:

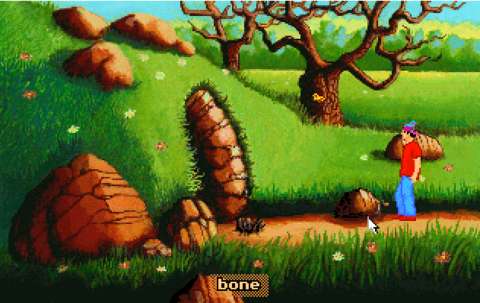

The player character is represented by a humanoid sprite with believable proportions for a Caucasian boy in his mid-to-late teens. His choice of colours for his clothes make him stand out in just about any scene, which is convenient.

Another example of the game’s very, very few good designs is his considerable movement speed. Mark’s sprite moves across any scenery very quickly, which is just as well, because the player would be doing a lot of backtracking.

His mother provided him with “trousers with BIG pockets”, to quote Mark’s own words. This is, of course, the excuse for the unbelievably spacious inventory which he has, not unlike those which so many other comical adventure game protagonists have.

RIGHT-CLICK PROMINENCE:

Where most of its contemporaries used the left-click of the mouse to do most things, Teenagent uses the right-click. This can be slightly off-putting at first, though most players should be able to adapt. Still, this noticeable difference suggests that the creators of the game seems to be out of touch with the norms of the genre, or are just being deliberately non-conformist.

INVENTORY SYSTEM:

Like other adventure games at the time, there is a screen which shows the items within the inventory. The items are represented as pictures of themselves, which is par for the course at the time and is thankfully also the case for this game.

What is not the case for this game is that there is no dedicated button to open the inventory system with. Instead, the player has to hover the mouse cursor along the top edge of the screen and wait a couple of seconds for the inventory display to appear. This can be tedious.

AWKWARD LINES:

The game’s creators happen to be Russian. This would not have been a problem, if their grasp of English had been impeccable. Unfortunately, this is not the case, so there will be plenty of monologue and dialogue lines with noticeable flaws in them.

For example, there is a barman who keeps saying “Miss” whenever the protagonist tries to make a guess at what order is free for the day; the barman should be saying something along the lines of “Nope”.

Another example is the protagonist’s description of an old retiree; he called the latter a “retired sea wolf”, when the proper phrase should have been “sea dog”, in reference to a salty and hardened sailor.

Perhaps the game’s creators could have benefited from having someone else proofread their writing, but they did not.

SOME SOLUTIONS ONLY REASONABLE IN HINDSIGHT:

For better or worse, there are puzzle solutions which would only make sense after the player has obtained it (through chance or trial and error).

For example, there is a bored guard who is doing just about anything to keep himself occupied, including counting leaves. One of the puzzles which concerns him happens to involve exchanging a kaleidoscope with the gazetteer which he is reading. In hindsight, it would seem reasonable that he would want the kaleidoscope. He also says something about the kaleidoscope just before it was handed over.

Yet there is nothing to suggest that he would like a kaleidoscope before this happened; none of the other characters on-location appear to make any remark that would imply this either.

SOLUTIONS FROM RAMPANT TRYING OF THINGS ON OTHER THINGS:

One of the most pervasive complaints about the adventure games of yore is that their puzzles often had to be solved by trial and error. An example of this is the attempt to achieve a breakthrough by using an item on any on-screen object. Even in hindsight, the breakthrough would seem ridiculous.

Chief of these infuriating puzzles in Teenagent is the protagonist’s attempt to open a drawer. At this point of the game, the player might well have some tools, such as a Swiss army knife, which should reasonably be able to force open or circumvent a locked drawer.

However, it has to be opened with the use of an explosive device, the safety pin of which is to be pulled by a cord-like object. This in itself can seem like overkill. Even worse, through an attempt at slapstick humour, the usefulness of the cord-like object is rendered moot.

Another example is the deliberate dirtying of a feather duster by using it on a fireplace (something that is terribly foolish in the real world indeed). One would wonder what the dirty feather duster does. Eventually, after trial and error with the other objects in the inventory, it is to be used to somehow paint a potato such that it looks like a grenade.

A LOT OF SLAPSTICK COMEDY:

For better or worse, there are a lot of puzzle solutions which have the player character abusing other characters to comical effect. Mark will be jolting someone with electricity, having someone drink a mug full of mud and drugging a pigeon with sleeping pills, among other things.

Perhaps there would be people who still appreciate this kind of humour in an adventure game. Otherwise, this kind of puzzles has not had a common presence in the genre since this game’s era.

PLENTY OF HARM TO FICTITIOUS ANIMALS:

Unlike the protagonists in many other adventure games of the time, Mark gets to hurt a lot of animals. The most overt example is firing a shotgun at some birds, one of which visibly falls.

Personally, I am very much amused by these because they are not common in video games, but other people might be perturbed.

PUZZLES REQUIRING HANDYMAN KNOWLEDGE:

Then, there are some puzzles which might require the player to have some knowledge about home-made substances or do-it-yourself techniques. For example, there is a puzzle which involves fuelling a chainsaw with high-percentage alcohol, which in real-life can be done but does not always yield reliable results.

FRUSTRATING TIMED-CLICK PUZZLE:

Unfortunately, there is a puzzle that has been needlessly made more complicated. This is the puzzle about getting an anchor from the bottom of a lake.

Now, of course, there is the protagonist’s own excuse that he needs to have enough air in his lungs to get to the anchor in time. However, this excuse is implemented in-game as a small window of time in which to click on the anchor before the protagonist went too far in his automatic swimming animation.

In more competently designed contemporary games, there is a timer which ticks down to zero in situations that involve limited air or exposure time. This timer runs down while the player still has control over the player character. That Teenagent could not even reach this bar already speaks volumes about the skill – or lack thereof - of its designers.

NONSENSICAL PUZZLES:

Last but not least, there are puzzles which simply make little sense, whether in their requirements, means or results.

For example, there was the aforementioned puzzle solution of somehow painting a potato to look like a grenade with soot. One would think that the “grenade” can be used to trick someone else, but it turns out to be not a dud.

Another example is the sharpening of a sickle with the winch shaft of a well. Yet another example is the use of a heart-shaped orifice in a piece of furniture to somehow remould a piece of candy. Then there is a “dart”, made from a pine cone, a feather and a needle; dartboard aficionados would shake their head in disbelief at this.

Granted, Teenagent was not the only adventure game at the time that had such puzzles. Yet, prevalence was and should not ever be an excuse for incomprehensible ‘puzzles’, especially if they are used to boggle customers and inveigle them into calling premium hint-lines. (In fact, the game does not have any hint-lines, so the players of days of yore would have had to learn the solutions on their own.)

DIALOGUE & MONOLOGUE:

Much of the dialogue and monologue in the game is the result of the writing’s attempt at being comical. Some of the lines are actually effective at expressing humour, such as most of Mark’s monologues about his slacker habits.

However, the other lines are just not as effective. One of the reasons is that they make use of a lot of long pauses, presumably to emphasize awkward moments. Perhaps they would have been funnier if they were fewer of them, but there are so many of these that they become stale.

VISUAL DESIGNS:

Fortunately, the developers were not so lackadaisical with the game’s visual designs. For a game of its time, Teenagent has a considerable amount of animations for its sprites, all of which appear to be done from scratch. As to be expected, Mark has the lion’s share of animations for being the protagonist of the game.

Conveniently and typically, sprite animations are used to indicate what the player character could interact with, or in the case of red herrings, remark on.

The sprites and the environments have a very noticeable cartoonish presentation. Examples include the exaggerated eyes and head sizes of animals. In hindsight, these were perhaps necessary, without which they might have been difficult for the player to recognize as animals.

However, the player might notice that certain ranges of colours are prevalent for almost the entire game. Hues of brown, yellow and green are particularly prominent, as is evident by the noticeable pervasiveness of plant-life in just about any locale.

Perhaps this was because the game was also made for the Amiga, which was a robust platform for its time but ultimately one that was already aging by the time of this game.

SOUND DESIGNS:

The music is composed by Radek Szamrez. It is perhaps the only thing in the game that is completely worthwhile. There is a surprising variety of tunes in the soundtracks, though most of them are uppity tunes as befitting the game’s attempt at projecting a comical atmosphere.

There is no voice-acting whatsoever; in fact, human characters do not utter anything at all. Some animals do have sound effects, though these do not always match what the animals should sound like. On the other hand, all slap-stick occurrences always have sound effects, and these are typically whimsical noises.

SUMMARY:

Teenagent wears its influences on its (short) sleeves, but it does not always emulate the best parts of its sources of inspiration. It tries to copy their humour, but overdoes it to such a point that it is more frustratingly incredulous than amusingly silly. Also, it repeats a lot of their bad practices. The worst among these is the implementation of ridiculous puzzle solutions which would have necessitated the use of the infamous hint lines that the classic titles were notorious for.

The Good Old Games store may have made Teenagent free to every customer, but it is just not worth the time to play when there are so many other better free titles to play.