The Secret to Valve's Success

Half-Life developer's new employee orientation manual underscores the benefits of a major player in the industry who isn't publicly traded.

A digital version of Valve's Handbook for New Employees has been making the rounds online (embedded below), and it highlights the numerous fascinating and unconventional ways the company works, from its total lack of management to its active discouragement of development crunch. That's all really cool, but there's one thing about Valve I value more than anything else. It's summed up in just two sentences at the start of the handbook, but it's by far the most important trait of the company, the prerequisite foundation without which none of the company's other distinctive aspects could exist:

"Valve is self-funded. We haven't ever brought in outside financing. Since our earliest days this has been incredibly important in providing freedom to shape the company and its business practices."

The important thing here is that the reportedly $3 billion company is privately owned, and not subject to the same pressures as publicly traded companies like Nintendo, Microsoft, Sony, Activision, Electronic Arts, Ubisoft, Konami, Capcom, THQ, and pretty much every publisher in the industry. Once a company goes public, management is duty bound to grow shareholder value in the company. It's no longer enough to keep the lights on and turn a steady profit; the business needs to grow. This summer needs to be bigger than last summer. Next year needs to be bigger than this year. It wouldn't be sufficient to simply turn the same profit every quarter year in and year out, because a company with a stock price that never changes isn't giving shareholders much of a return on their investment. So if a publisher fails to grow for too long a stretch, investors sell their stock, the share price tanks, and heads roll in upper management.

The result of this system is that long-term planning can be sacrificed to bolster the bottom line in the short term. It's tough to point to examples of this since nobody wants to confess to them, but it's not too difficult to speculate about what happened to Namco Bandai's Ridge Racer Unbounded last month. The publisher had announced a March 6 release date for the Bugbear-developed racer, but on that day instead released an announcement explaining that the game had been pushed to later in 2012 to add new features. That would also give the publisher time to properly promote the game, as the publisher said it would soon unveil a preorder incentive program for the game.

That didn't actually happen, as the delay was the last Namco Bandai said of Ridge Racer Unbounded until the game quietly appeared on store shelves March 27, just four days before the end of the publisher's fiscal year. Reviews varied wildly (GameSpot gave it an 8.0), but Metacritic recorded 28 positive reviews and just four negative. It's difficult to believe that a publisher without the need to bolster its full-year fiscal results would take a game as good as Unbounded--exactly the sort of game that could have benefitted from a proper marketing build-up--and push it out the door with so little fanfare.

"We are all stewards of our long-term relationship with our customers. They watch us, sometimes very publicly make mistakes. Sometimes they get angry with us. But because we always have their best interests at heart, there's faith that we're going to make things better, and that if we've screwed up today, it wasn't because we were trying to take advantage of anyone."

Valve isn't alone with paying lip service to that idea of valuing the customer above all else, but it has precious little company in being able to claim this with a straight face. It's easy to look at the success of Assassin's Creed and Call of Duty and think of Ubisoft and Activision as prisoners of their success, practically forced to release new installments every November or grimly explain to shareholders why their key holiday quarter revenues took a nosedive. It's just as easy to view Blizzard's Diablo III auction house as a money grab for the publisher, or the fact that the game will launch without the player-versus-player arena as a bottom-line-inspired abandonment of the company's standing release window for all its products: "When it's done." Contrast that with Valve's approach to Team Fortress 2 or to Half-Life 3. The studio took an agonizingly long time to launch the former, so much so that it wound up on countless vaporware countdowns. As for the latter, Valve hasn't publicly touched the franchise since Half-Life 2: Episode Two launched five years ago, no doubt leaving a not insignificant amount of money on the table in the process. But where a publicly traded company would consider money leaving and tables to be the stuff of night terrors, Valve has stuck to its guns on the subject. It knows there's a demand for Half-Life 3. It will doubtlessly make the game at some point. But it doesn't need to force a Half-Life 3 out the door to meet quarterly projections or revenue targets.

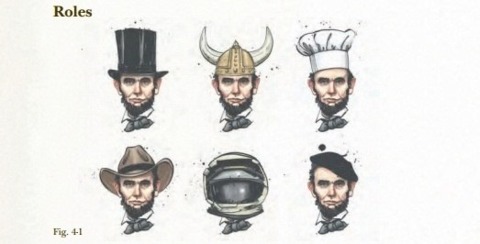

Those who read through the rest of Valve's employee handbook will be given a peek inside an entirely unique corporate culture, where new hires decide what they want to work on, nobody has a title, and moving desks is as simple as literally pushing one's desk wherever in the office it needs to be. There is one more part that bears highlighting here, however. And that's the single-question FAQ at the end of the handbook:

Q: If all this stuff has worked well for us, why doesn't every company work this way?

A: Well, it's really hard. Mainly because, from day one, it requires a commitment to hiring in a way that's very different from the way most companies hire. It also requires the discipline to make the design of the company more important than any one short-term business goal. And it requires a great deal of freedom from outside pressure--being self-funded was key. And having a founder who was confident enough to build this kind of place is rare, indeed. Another reason that it's hard to run a company this way is that it requires vigilance. It's a one-way trip if the core values change, and maintaining them requires the full commitment of everyone--especially those who've been here the longest. For "senior" people at most companies, accumulating more power and/or money over time happens by adopting a more hierarchical culture.

Got a news tip or want to contact us directly? Email news@gamespot.com

Join the conversation