Telltale and the Value of Episodic Content

Laura Parker speaks to Telltale CEO Dan Connors about the success of The Walking Dead and why episodic content could be the way of the future.

Last December, YouTube user OfflimitsPC, or The Girl from Aus as she's better known to the 500+ subscribers to her channel, uploaded a video of herself playing through the final episode of Telltale's The Walking Dead. The Australian teenager's reaction to the final scene of the game, in which she swears, sobs, and tells the developers of the game to f*ck off, caught the attention of Telltale CEO and The Walking Dead executive producer Dan Connors, who included her video in his 2013 DICE Summit presentation on the merits of episodic content. Connors' purpose was simple: to demonstrate the level of investment players can have in video game characters, if only given the chance.

* * *

California-based Telltale Games has turned episodic content into an artform. The studio, founded in 2004 by ex-LucasArts employees Dan Connors and Kevin Bruner, has shown steadfast dedication to the same business model for the last nine years. Episodic content is the foundation of Telltale's design philosophy, driving development on almost all the studio's past games and earning Telltale a reputation for high-quality entertainment that pushes the boundaries of established distribution methods. Strong Bad's Cool Game for Attractive People (2008), Wallace & Gromit's Grand Adventures (2009), Tales of Monkey Island (2009), Back to the Future: The Game (2011), and Jurassic Park: The Game (2011) were all developed with this philosophy, guided by the belief that piecemeal episodic distribution, coupled with a strong narrative focus and the use of licenses as a way to reach existing fanbases, would lead to success in a growing digital market populated by audiences demanding smaller, more user-friendly gaming experiences at lower price points. But it wasn't until 2012's The Walking Dead, a five-part adventure game based on Robert Kirkman's comic series, with its difficult choices, its critical and commercial acclaim, its 80 Game of the Year Awards and its videotaped moments of heartbreak, that Telltale's commitment to episodic content finally paid off.

* * *

"Plenty of business models were falling off the cliff at the time," Connors says, looking back at his and Bruner's initial direction for Telltale. "We could have chased the trend-setters, the casual, social, mobile, or free-to-play models. There was always the lure of the latest get-rich-quick scheme and the fear that if you didn't get involved you would miss out."

"But it didn't feel like it was our thing. It wasn't what we did and it wasn't what we knew. We knew about building stories based on licenses, and we thought the best way to distribute them was episodically. So that's what we did."

Telltale's games have sold well, and, for the most part, have been favorably reviewed. But, before last year, none really managed to make an impact. Some even dragged the studio backwards: 2011's Back to the Future was regarded as an easy adventure game with a great story, but without much choice and consequence to back it up; Jurassic Park shifted gears towards more dramatic pacing and tension but ran into trouble creating believable characters and incorporating a strong gameplay element: while commended for its story and clever references to Spielberg's original film, the game was criticized for being rigidly linear, not placing enough importance on consequences, and having puzzles that were simply too easy to solve, leading some reviewers to conclude that the game was fun to watch but not that much fun to play.

Connors acknowledges that both games were attempts to bring gaming to a wider audience, something that longtime Telltale fans did not appreciate.

"We started to move away from traditional gaming mechanics and that put us in a nebulous state as far as how people felt about our games," he says. "Both games sold well and were profitable for us, but I don't think we had quite landed either the narrative or the gameplay formula when they were released."

After deliberating on what went wrong with each title, Telltale was ready to try again.

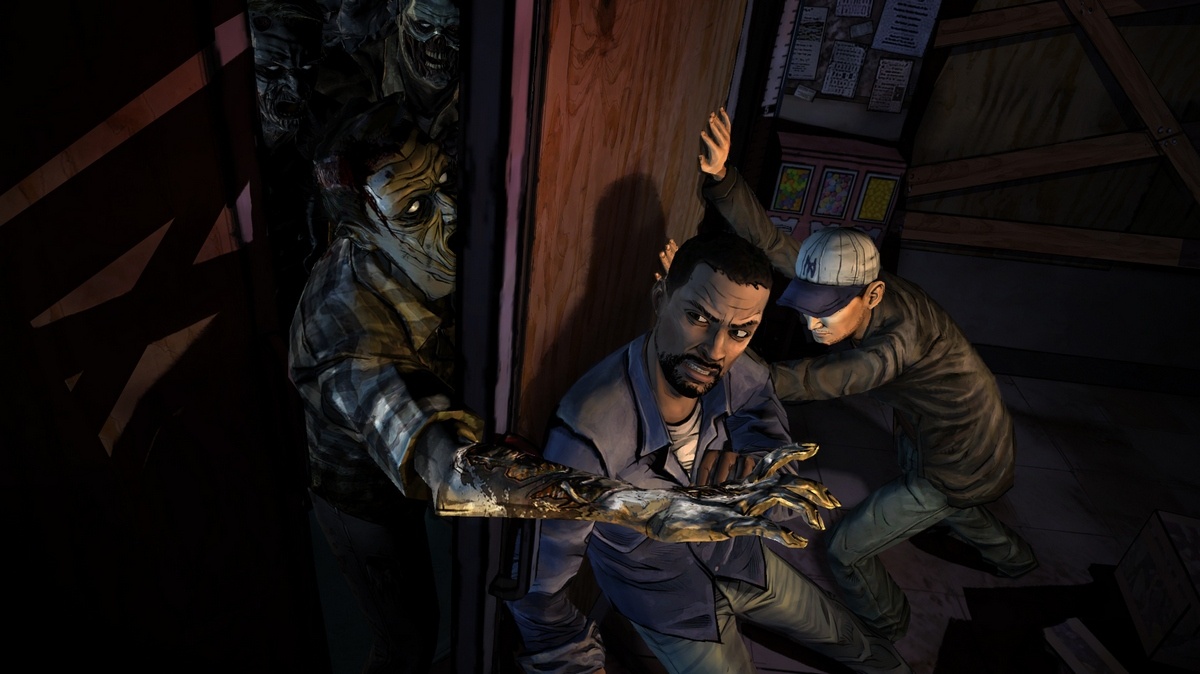

The debut episode of The Walking Dead: The Game was released on April 24, 2012, with four more episodes released between April and November the same year. The game follows university professor and convicted criminal Lee Everett, who is joined by an eight-year-old girl, Clementine, in post-zombie outbreak Georgia. Choices made by the player in the game carried through from one episode to the next, allowing Telltale to record how players behaved in certain situations and giving them an idea of how relatable the characters were. Not surprisingly, the majority of players became invested in protecting Clementine, whose relationship with Lee became a major focus of the story.

The game was a hit, selling 8.5 million episodes to date and earning Telltale critical acclaim across the industry. Connors describes the game as "the quintessential version" of Telltale's design philosophy, a culmination of over eight years' hard work perfecting a very particular style of narrative gameplay on multiple platforms. In Connors' eyes, The Walking Dead is the perfect example of an episodic adventure game.

"With all due respect to The Walking Dead brand, I think if Telltale had delivered a game with the same kind of narrative gameplay [without The Walking Dead license], it still would have been one of the most interesting games of the year, just for what it was capable of making players feel," he says.

For one, the game managed to be believable, presenting the same kind of unromanticized world view of humans grappling with a zombie apocalypse as Kirkman's comics and AMC's The Walking Dead television series. This wasn't the world of Left 4 Dead, Dead Rising, or Dead Island: players' decisions were met with believable reactions from the game's characters and consequences were not always immediately obvious. Secondly, there was something about these characters that made it impossible to remain apathetic to their fate. The more people played, the more obvious it was the choices they made stayed with them.

Once people started writing in to Telltale to share their experiences of playing the game (some good, some bad), Connors realized just how much people viewed their experience in terms of their relationship with the characters. Even in playtests, people always seemed to make decisions based on how they felt about the individuals in the game: they didn't want to piss someone off, make so-and-so sad, or lose someone's trust. Very rarely was a decision based on logic, and that felt good: it proved to Telltale they were onto something.

"That's when we started looking at how we could make the stakes really high, episode to episode," Connors says. "The writers were merciless…I remember fighting for Carly in all the meetings and they just wouldn't hear me out. [Carly gets shot in Episode Three.] They actually went back and added all the flirty exchanges between Carly and Lee once they'd worked out she was going to die, in order to make her character more lovable before killing her off. I couldn't believe it."

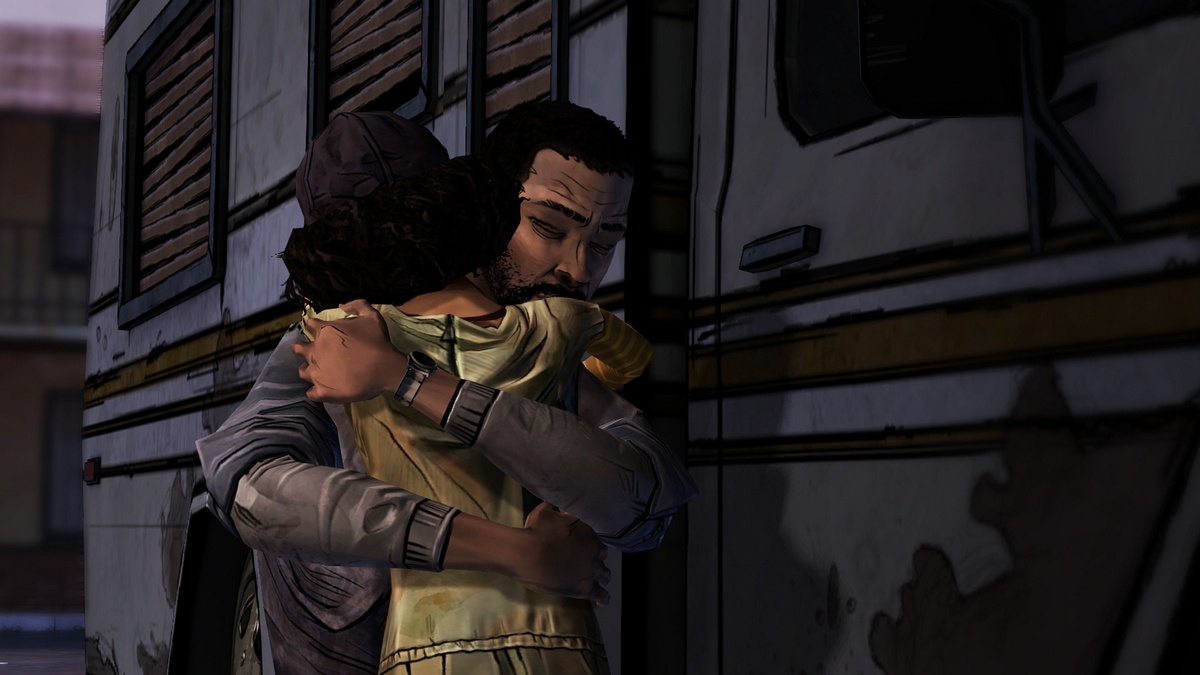

But it was the relationship between Lee and Clementine, with its tender moments and heartbreaking ending, which helped bring the whole thing together. In many ways, this is what The Walking Dead is about.

"The power of that relationship blew us away. We couldn't believe how much it impacted on people. Almost every single player chose to save Clementine over themselves…she almost became the goal in the game."

While the success of The Walking Dead came as a surprise to Telltale, most of the studio's earlier predictions about the changing nature of business models in the games industry had come true, from the onset of digital distribution to the demand for shorter, cheaper content. At last, the climate was right for episodic to succeed.

"We always get asked why we stuck with episodic for as long as we did," Connors says. "The Walking Dead is why. I know it's not immediately obvious, but we made progress with each new game we made. It wasn't moving as fast as we would have liked, but every step of the way there was enough there to show that this could work as a business model. And finally, we proved it could."

* * *

Episodic content is quickly gaining traction as a viable business model. Sony has already announced its newly-unveiled PlayStation 4 console will support both episodic and free-to-play games, while content creators like Metal Gear designer Hideo Kojima have been quick to champion the use of TV-style "pilots" to combat the challenges of next-generation console development based on the idea that developers could trial products to see if players are interested before moving forward. It's an attractive premise for the games industry, more so because it promises to tap into an existing audience already accustomed to getting their entertainment in weekly or monthly doses. Some developers are already experimenting in this area: April will see the worldwide debut of Defiance, an open world, multiplatform MMO developed by Trion Worlds which will be released alongside a global television series on US network Syfy. The developers promise that both the show and game will feed into each other over time, creating a new experience that appeals to both gaming and television audiences.

These are the kinds of opportunities Connors imagines episodic content will allow game developers to explore. Echoing Quantic Dream founder David Cage, Connors believes the game industry should form a closer bond with Hollywood to create new experiences that seek to bridge the gap between passive and active media and draw in new audiences in the process.

"We need to work out how we can build something that works going forward, something that will stop us from falling back into old habits," he says. "Old habits have left us with nothing but layoff after layoff and studio closure after studio closure. Interactivity is our area of expertise: we should own it. We should take advantage and kick ass."

This is not to say that all game developers should stop what they're doing and start making episodic games. This isn't about taking a finished retail game and splitting it up into five pieces: the model is not designed to work for every genre of game, nor will it. But the market is showing interest, and the more interest it shows, the more the industry needs to respond.

"The market is the one forcing the transition between different channels and platforms now, not technology," Connors says. "It's not easy to build a game that you can sell on XBLA, PSN, the PC and the iPhone all at the same time. But this is what people want, and we have to start giving it to them."

'Got a news tip or want to contact us directly? Email news@gamespot.com

Join the conversation