INTRO:

Unity and RPG Maker are relatively simple tools for game developers to use. However, whether they could make something truly special is another matter. In this regard, it is unfortunate that quite a number of games that has been made with these, especially in the indie scene, are mostly forgettable. Even if some of them can be remembered, they might be remembered for all the wrong things, like awful glitches.

Freebird Games’ title is an exception. It is easily memorable, and for things that buck the typical norm about RPG Maker titles.

AUTOMATIC PAUSING WHEN SWITCHING TO OTHER PROGRAMS:

Conveniently, when the player switches out of the game to peruse some other game, the game pauses its gameplay scripts, though the current music track and ambient sounds continue to loop.

This has been a pleasant experience for me personally, because it made so much easier to write notes and take screenshots of the game.

MUSIC:

To The Moon begins itself with perhaps its best element. Some of the music is composed and vocalized by the talented and skilled Laura Shigihara. The music is further augmented by tracks composed by Kan Gao himself, who made some of the near-chiptune tracks. There are many tracks distributed throughout the game, and to the developers’ credit, they have associated the most appropriate ones with the scenes.

Indeed, most of the tear-jerking urges that the player would feel can be attributed to the music. Thus, it is perhaps understandable that there is no option to disable the music whatsoever.

Alternatively, the player could disable any audio signals in order to play the game without music. Indeed, without it, some of the brevity of the various situations is diminished, especially for the moments when scenes transition to emphasize a different emotional state for the main character.

SURPRISINGLY DETAILED SPRITE ARTWORK:

Most RPG Maker titles are characterised by artwork that are not a lot better than the ones that had been seen for JRPGs on the SNES. However, the artwork for this particular RPG Maker is surprisingly detailed.

For one, the amount of effort that has been invested into making details in the environment is considerable. Of course, sceptical players may notice that certain sprites have been duplicated, such as those for flowers of the same species. Still, even the copies had been distributed carefully that the duplication is not immediately obvious.

Experienced video game buffs may even notice that the amount of detail in the artwork for this game would rival that for Chrono Trigger, which is arguably one of the visually richest old-school JRPG that has been made.

There are also some scenes that are not sprite artwork, though they have been drawn and coloured such that faces are conveniently not shown. Perhaps this was done with the intention of letting fan artists have their imagination run wild.

Suffice to say, To The Moon is very, very much not a lazy piece of work, despite one glaring omission that will be described shortly.

NOT A JRPG:

Most RPG Maker titles are JRPGs. If they are not JRPGs, then the player character is still someone that may have statistics and variables that are needed for some kind of visceral performance, e.g. combat.

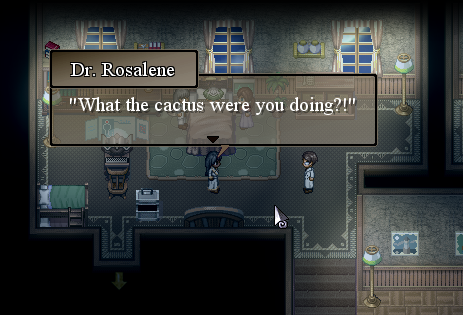

To The Moon is not such a game, and it makes itself clear that it is not one through a gag scene that occurs early in the playthrough.

Of course, one could argue that it is not the first RPG Maker title to be not a JRPG. 1996’s Corpse Party was not one, for example. However, that game and some of its remakes make use of a hitpoint meter, which in turn is used to implement an element of stress in the gameplay.

To The Moon does not have a hit point meter at all. In fact, the most that it does with RPG Maker’s features is to implement an inventory system.

That may suggest that the player character would be going around collecting things and using them on other things, or giving it to people. That is not the case either. However, hindsight would give a strong impression that the game had been intended to be an adventure game, in that it is intended to tell a story.

Still, the experienced game consumer can already expect that there is not much gameplay to be had, upon hearing that the game is oriented around story-telling. Still, there is a bit of gameplay to be had – a bit.

LACK OF USER OPTIONS:

As mentioned earlier, the game lacks an option to disable sounds in-game. Unfortunately, there are many other options that are also not implemented. These are options that long-time game consumers would have taken for granted, like audio volume and even window size. The screen display is also locked to 4:3, which is rather disappointing.

PREMISE:

It is unclear what kind of setting that To The Moon has. It appears that it is set in around the near-future, with flashbacks to an earlier era for scenes involving characters’ pasts. However, there is also the presence of esoteric technology, notably the memory-altering devices that Sigmund Corp. has.

For whatever reason, instead of being outright outlawed, this technology was granted the right for commercial use. Specifically, it would only be used on terminally ill customers, who want to have their memories altered such that they believe that they led a fulfilling life.

This is a head-shaking and eyebrow-raising premise, and it is something that is not discussed in the story-telling. For one, how the permission for the use of this technology came about is not entirely explained, and would perhaps be explored in a later instalment.

(It should also be mentioned that some years after the release of the game, some scenes have been introduced such that it is implied that there is something sinister going on. Of course, there would not be any speculation for this in this article.)

Anyway, the player characters – there are two – are employees of Sigmund Corp., educated and trained for operating one of the aforementioned devices. Their current client is a dying man who wants to believe that he has achieved his dream of being an astronaut – except that he has problems remembering why he wants to do so.

Most of the game will revolve around the present-day and memory-based flashbacks. The present-day segments are often about the dilemmas that the two Sigmund employees face about how to best bring about the false memories without causing cognitive dissonance, while their time with the client runs out. The flashback moments have the employees mostly acting as bystanders, watching the customer’s life go by. Then, they would make the climatic decisions on where to make alterations.

THE SIGMUND EMPLOYEES:

Ethical issues about tweaking memories are a common theme throughout the game. Conveniently, the two Sigmund employees have near diametrically opposite personalities. One is a tad reckless, whereas the other is more conservative; both are determined to bring results, albeit with differing opinions. This is obviously not the most harmonious of professional pair-up, but Sigmund Corps works in peculiar ways, as befitting its commercial use of peculiar technologies.

Other than their professional quarrels, many of the humorous scenes will be about banter between the two, as they make pokes at each other’s level of skill and personal inclinations.

THE DYING CLIENT:

The dying customer is the protagonist in the story, which is mainly about his life as the memory-diving device goes through his memories.

He begins as an old man at death’s door, with little ability to recall his memories. Thanks to the memory-diving machine, the player gets to see his more and more of his past personality, prior to the depression that sets in after the last tragic event in his life.

There would be significant revelations about his past, and how it is tied to his relationship with a certain loved one.

A CERTAIN OTHER MAIN CHARACTER’S CONDITION:

As the story progresses, an experienced story-goer would eventually recognize that most of the plot concerns a certain complicated condition that a small segment of humanity has. When coupled with the theme of memories and people’s general inability to link decades-long experiences together, the story expresses some of the tragic limitations in humans’ ability to interact and relate to each other.

Apparently, drugs were involved too, but to elaborate any further would be a spoiler. Suffice to say that this discovery and the next scenes that come after would link all of the earlier scenes in the playthrough into a wonderfully tragic conclusion.

OTHER CHARACTERS:

Interestingly, the other characters are introduced via a plot progression that works its way from the client’s lonelier and older years towards his younger years, when he had more contact with other people. The significance of these characters to his life are revealed, together with the reason for his choice to live in the “middle of nowhere”, to quote one of the player characters.

Not many stories could be told in such a manner – one example is the film Memento. Indeed, most of them could not be told without resorting to some outrageous gimmick, like Memento’s protagonist lacking any short-term memory and in the case of this game, a technological doohickey.

MOVING AROUND:

Like any other adventure game, the player character would be moving around, looking at things. The game uses the control system for player characters in RPG Maker, but it also incorporates the use of the mouse, likely with the implementation of code from Unity.

Thus, the player characters move like they do in typical JRPGs: always ever in the four cardinal directions. Indeed, the player characters move like a typical 2D JRPG party, with the trailing characters practically replicating the movements of the leading character with lags between them.

However, they move along paths that have been generated by the path-finding scripts, which in turn use information on the whereabouts of the player characters and the destination to do their work. The paths are not always efficient though, and sometimes the player characters do silly things like circling around an object along the longer arc instead of the shorter one.

LOOKING AROUND:

Conveniently, just like in competently designed adventure games, the mouse cursor turns from an arrow into something else when it is over something that the player characters can examine or interact with. Again, like in adventure games, the player characters make remarks on what they examined.

However, since most of the gameplay takes place in memories, the player would not be using things on other things like the player would in typical adventure games. Rather, all the player needs to do is look around.

Indeed, it is not too difficult to make progress. All the player needs to do is have the player characters saunter about and move the mouse cursor over anything that might be of interest. Pixel-hunting is usually not needed, fortunately. (However, the windowed mode of the game squashes visuals to a small size, so things that are small already would look even smaller.)

Interestingly, most scenes occur such that the player is given a visual cue to go somewhere. Of course, the player could just have the player character wander off elsewhere. The player is not always rewarded for doing so, for there might be nothing worth noting elsewhere in the map for the current scene.

CURSOR CHANGES SOMETIMES FAIL:

Unfortunately, the designs of the boxes for the regions where the mouse cursor would change are not reliable throughout the game. There are some segments where they might not work, or work intermittently if they do.

Fortunately, sometimes all the player needs to do to progress is have the player characters bumping into important things. The scripts that are associated with those things would trigger anyway.

INVENTORY:

Seemingly, the player characters would be collecting things like any player character in other adventure games. Ultimately though, due to the memory-diving part of the gameplay, having physical objects is not needed to progress in the story. They can be collected to fulfil some “achievements”, e.g. the ones that had been included in its Steam release, but they do not have much impact on the gameplay.

The Inventory also includes notes on things. Interestingly, these notes are updated as the story progresses, and they help the player recall pertinent things that were revealed earlier.

MEMENTOES:

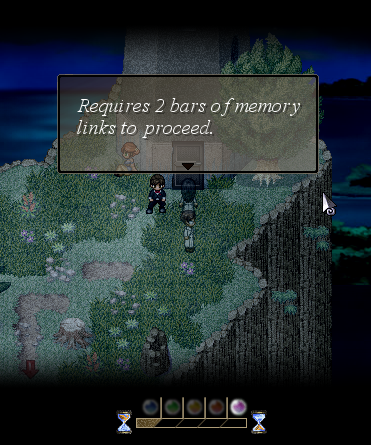

Speaking of mementoes, these are the main thematic gimmick in the story-telling. Due to the client’s old age and trouble at remembering things, the player characters have to resort to focusing on objects that have sentimental value to him. These objects appear in the flashback scenes too, and somehow, they can be used to access his earlier memories.

On the other hand, again due to his old age, likely depression and value of privacy, the mementoes are initially “shielded” against any use. Conveniently, the memory-diving device can remove this shield by “linking” associated mementoes to it. The player characters have to find these links, however, and somehow collect them like one would collect data, or to be more precise, ammunition. The links are then “fired” at the shield to break it – something that the more disrespectful player character rather relishes.

CONVENIENT BUT ODD LINKAGES:

The memory links to remove a shield are only ever found in the same scene, which is perhaps somewhat understandable if the perspective of time is considered. However, the emotional association between the memory links and shielded memento is not always convincing, at least in the current scene and the next one.

For example, there is a scene about the protagonist’s dilemma about spending money on an important thing or another important thing. The memory links are relevant to the dilemma, but the memento is a jar of pickled olives, of all things. Apparently, the design choice of the pickles is that it is one of the small things about his married life, which is the next scene.

The reason for all these odd linkages is, fortunately, revealed at the penultimate act of the story. It would take quite a cold-hearted cynic to still be somehow sceptical of the associations.

TILE-FLIPPLING PUZZLES:

One of the few portions of the gameplay that would challenge the player’s deduction skills is the tile-flipping puzzles. In these, the player clicks on buttons to flip entire rows or columns of tiles, in order to completely reveal the image under the tiles. There is also a button to do a diagonal flip.

These come up whenever the player wants to use a memento to travel to another memory. These are mandatory parts of the game, so players who are only capable of playing games that are not more complex than storytelling-oriented titles may be in trouble.

To anyone that has significant intellect or more experience with tile-based puzzles, these are simple. The player is given all the time that he/she wants to plan tile flips. Since flipping tiles only ever produces a certain result for any single tile, it would not take long for a seasoned player to come up with a set of moves that efficiently solves the puzzle.

The game does show the least number of moves that is needed to solve any puzzle. This would egg the player to come up with an efficient solution, and it also gives a hint for the sequence of moves for that solution.

Interestingly, there is a counter that records the total number of moves that the player has made for all puzzles thus far. There is no hidden story content that is associated with this counter, however, but it is there for an “achievement”.

OTHER PUZZLES:

Most of the other puzzles in the game are one-off scenarios, and they are relatively easy for anyone who have the capability to do logic puzzles. Veteran followers of adventure games would know this all too well, as do people who have played story-oriented RPGs.

Developers sure love to include such pace-breaking tidbits.

SOUND EFFECTS:

Most of the sounds that the player would hear in the game belongs to its musical composition. However, there are some other minor sound clips to be heard, such as for doors opening (which is of course the sound effect that is associated with some character entering the scene).

The use of the sci-fi memory-altering device also means that there would be digital sounds, such as those used for when mementoes are accessed. Perhaps the most important of these are when the player finds memory links, and when enough have been collected to remove the shielding on mementoes.

SOME REFERENCES:

Many indie game developers have a penchant for including references to other works of fiction. Freebird Games is not an exception. In the case of this game, it made references to certain books, including a series of books with a modern/sci-fi setting.

This is mentioned in this article because fans of that particular series of books had pointed out that one of the references may not have been made correctly. On the other hand, the character that was mentioned in the reference is a very minor character with few appearances throughout the series and without any noticeable consistency in his character development.

Some of the references come from the player characters’ lines. For example, the more boisterous one makes a reference to one of Hayao Miyazaki’s works, specifically the one about floating castles. However, unlike the other references, these are mainly there for humour.

SUMMARY:

To The Moon is not a long experience, so there could be plenty of quarrels and arguments over how much value it has. Still, it would become the start of what would be a series of games from Freebird Games, all tied into the same universe. In hindsight, all the money that was spent by consumers on this game did amount to something more later, as is evident by the release of a sequel and some related side-stories that tie the two together.

There is definitely one praise that this game very much deserves though – it is a tear-jerker.