INTRO:

A Midsummer Night’s Dream is Daedalic Entertainment’s next attempt at turning yet another work of William Shakespeare into a hidden-object game.

Unfortunately, A Midsummer Night’s Dream does not offer more than the banal gameplay of the previous title.

(A Midsummer Night’s Dream is sometimes packaged together with Romeo & Juliet in digital stores. This review has been placed under the Double Game Pack, but it is mainly about A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The user review for Romeo and Juliet is here.)

PREMISE:

Following the conclusion in Chronicles of Shakespeare: Romeo & Juliet, Daedalic’s William Shakespeare has been tasked to work on a comedy, which is the titular A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

One of his two patron lords, Ferdinando Stanley, is still supportive of him. However, the other lord, William Stanley, remains a cynic. Furthermore, he has tasked a theatrical editor by the name of Nicholas Rowe to challenge Shakespeare.

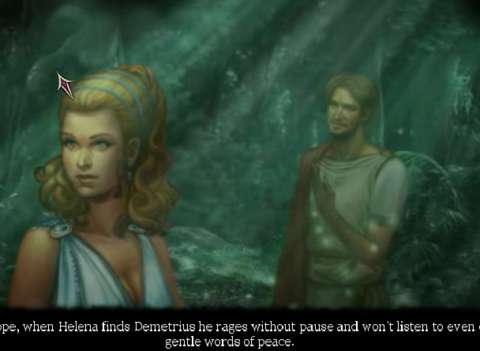

Shakespeare, with the help of Anne (the daughter of Ferdinando), will have to improvise the script in order to produce a memorable play of chaotic love and shenanigans. As for Daedalic’s rendition of the play itself, it is set in a fictitious and magical Greece, where elves are gods and humans are the hapless playthings of immortals.

OBJECT-HUNTING GAMEPLAY:

The player though, will be saddled with the boring task of hunting for hidden objects in scenes. Players who have played the previous game will be familiar with such gameplay – and probably disappointed or even disgusted too.

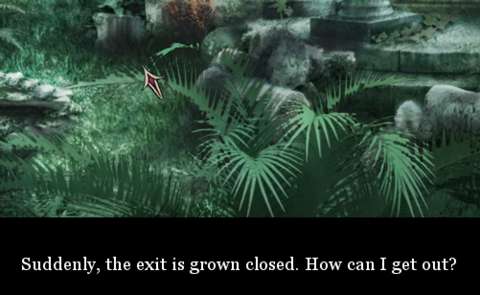

Like in the previous game, when Shakespeare starts to describe an act in his play, the player is brought into the scenes within the fictitious world of his story. The scenes have hidden objects.

These hidden objects are obscured by other objects within the pretty sceneries; the player is tasked with finding those objects which are needed to solve the current puzzle.

LITTLE SENSE IN OBJECT PLACEMENTS:

Items are lying all over the scenes, seemingly randomly and for sometimes no discernible reason. For example, the player might find sickles and hammers in unlikely places, such as holes in trees.

One could argue that a certain roguish non-mortal character has set these up for the mortal characters to find, but this argument falls apart in scenes which have the player taking on the role of this particular character. He himself has to find objects which are randomly strewn about too.

The random placement of objects can seem unbelievable. Of course, one could argue that the scenes’ fantastical settings would have ‘justified’ such lack of believability. Yet, if this argument is acknowledged and accepted, there is the complaint that the player would still have to check every nook and cranny for the things which he/she needs to find.

It is also worth noting here that this issue is not as pervasive in Romeo & Juliet. At least the characters in that game mention reasonable excuses for objects to be found all over the place. Consequently, the lack of sense in the placement of hidden objects makes the gameplay in this entry of Daedalic’s Chronicles of Shakespeare even more tedious than in the previous game.

OTHER PUZZLES:

Even Daedalic knows that finding one hidden object after another can be boring. Therefore, it has included some additional puzzles to cleanse the palate once in a while. Unfortunately, the puzzles which it has chosen are similarly banal.

There are the usual tile-sliding, duct-linking and object-swapping puzzles which have been seen in so many other puzzle-solving games.

Then there are puzzles which require simple motions, which can irritate players who do not like gimmicks. These also act as reminders that the game was intended for the touch-screen platforms too.

Some of the puzzles might also not have been designed with people who have vision problems in mind. For example, there are a few puzzles where the player must input colour codes, but the colours are a bit too similar in hues and shades for this to be comfortably achievable.

INCONSISTENCIES & VAGUE PUZZLE LOGIC:

Unfortunately, there are other problems which compound the tedium of the hidden-object gameplay and the boring familiarity of the other puzzles. These include inconsistencies in the presentation of some puzzles. There are also puzzles with logic which is so vague to the point of being allegorical or metaphorical.

For the elaboration of the complaints about vague logic, there are a few scenes in the game which can be used as examples. Early on in the game, there is a puzzle where one of the player characters, Demetrius, has to carve a statue of another character. For whatever reason, he must collect various objects which are allegories of the beauty of said other character.

Players who have better appreciation of the sublime can understand and perhaps even appreciate these puzzles. However, other players would be left scratching their heads as to why tiaras, rags and such could help in carving a humanoid shape out of a marble block.

Another example has even less believable logic. The player has to pick up a red-hot rock by creating a forceps out of twigs. Maybe people with vast outdoors camping experience can attest to this, but anyone else would have the impression that having dry twigs touch red-hot rocks is not a good idea.

The inconsistencies in the presentation of puzzles can be seen in the occasions where the artists for the game fail to keep in mind what they have drawn in earlier scenes when they are drawing a different but related scene.

For example, there is one scene in which the player can see a decapitated gargoyle (or cherub) statue. When the player is in the main view of this scene, the statue is holding a hammer with its left arm. When the player looks closer at the statue, the picture which is shown to the player has the statue holding the hammer with its right arm instead.

HINTS:

Like in the previous game, the player is told what to find; even if this is not done, a bit of logic would help the player to know what to click on before the game does so.

The hint-giving system in the previous game returns, though it is now represented with a beaker of self-replenishing green fluid instead of Anne reading a book. It still does the same thing: bright white swirls appear around objects which the player should check out.

At least there has been an improvement here; the hint system refreshes a lot quicker this time around, so the player can spend less time on tedious searching.

CHARACTER DESIGNS:

Most of the characters which are in Daedalic’s fictitious representations of Shakespeare’s early career return from the previous game. Shakespeare is still modestly dapper, the Stanley brothers are still foppishly upper-class and Anne is still a sweet little girl.

Nicholas Rowe (who, in real-life, is Shakespeare’s first editor) has been featured in the previous game, but he did not have a lot of screen time. He has more of that the second time around, for better or worse. He does come off a bit snarky (more so than the cynical William Stanley), but at least he expresses this through sophisticated sarcasm.

There is at least one new character: Nicholas Zettel, who eventually plays the role of the ass-headed mutant which the Greek goddess Titania would fall in love with when Shakespeare reveals the fourth-wall-breaking twist in his play.

There may be some confusion among literature buffs over this character, so the following passages are intended to clear it up.

Players who do their scholarly research will know that the ass-headed mutant is played by “Nick Bottom”. Nick Bottom plays as a member of the unlikely acting troupe that is the “Mechanicals”. The Mechanicals are a bunch of skilled labourers who are eager to have acting careers, both within the play itself (in its fourth-wall-breaking segments) and supposedly in real-life too.

Incidentally, the German recounts of William Shakespeare’s works name him as “Niklaus Zettel”. Therefore, Zettel’s character in this game may have retained his Deutsch surname, despite the translation over to English.

That Zettel’s surname has been retained instead of being written as “Nick Bottom” may give an impression that the translation has been done by people who could not give a damn about the Bard’s works. Of course, there is the irony that Zettel or Bottom may not have been real people at all; if they are not, then their names would not have mattered.

VISUAL DESIGNS:

A Midsummer Night’s Dream is set in a fictitiously fantastical version of Greece, so this gave Daedalic’s artists the opportunity to come up with vibrantly beautiful and surreal locales, more so than those in the previous game.

The mystical locales are particularly notable examples. There are groves of magical trees, gilded gates which function as portals between worlds and more than a few particle effects.

(In fact, they probably contributed the most to the game’s 1.0 gigabyte installation size; there will be more on this later.)

The same artstyle for characters has been retained, so the player can expect good-looking characters.

However, the same visual issues in the previous game return. The biggest of these is that the artwork for the characters is recycled in scene after scene, eventually diminishing their appeal and giving rise to the impression that the artists and animators are lazy.

SOUND DESIGNS:

As in Romeo & Juliet, the voice-overs are the best sounds in the game. The addition of Nicholas Rowe enriches the high-class English back-and-forth further. Zettel is the least pleasant of the characters, which is an irony considering that he is supposed to be a source of comic relief. Unfortunately, he is incessant at trying to be funny.

The music would have been great, if not for the interference of the background noises. These compete with the music for the player’s attention.

OTHER COMPLAINTS:

Daedalic is not exactly known for making technically sound games, even at this time of writing. It tends to miss a few glitches here and there, suggesting that its quality control is not thorough.

In the case of this game, there are at least no silly bugged puzzles like the one about a scale in the previous game. However, there are still problems, albeit minor ones.

For example, the progress record for the player sometimes only makes auto-saves at the start of an act instead of where the player left off when he/she quits the game. This problem does not happen as often – if at all – in the previous game.

For a casual game, A Midsummer Night’s Dream has some irritating verification processes during installation. Speaking of which, it has a big installation size too.

CONCLUSION:

A Midsummer Night’s Dream is little more than a continuation of the poor design policies which Daedalic has for its portrayal of Shakespeare’s works. Perhaps the only few things which are salvageable are the experience which its artists and sound designers get, and this happens to mature in Daedalic’s later games.