INTRO:

Obsidian has a spotty history in programming, but its followers recognize this spiritual successor to the long-defunct Black Isle for its stellar writers and ability to commit to the overarching story in its game. Thanks to this arguably skewed perception, Obsidian’s Kickstarter project for Pillars of Eternity was successfully funded. Furthermore, through PayPal, that project received even more funding afterwards.

After three years of development (one of which is spent in the “early access” phase), Pillars of Eternity, predictably, released with plenty of small bugs. Bug-fixing had to be done for close to one-and-a-half years.

Yet, despite this less-than-flawless launch, Pillars of Eternity was hailed as an excellent game that revived the Western RPG genre, at least according to its fans. This might seem to be too much praise, but an experience with the game would reveal why it is feted so much.

(The game still has technical issues to this day, of course. Obsidian is just like that.)

PREMISE:

Obsidian’s writers and designers crafted a new fantasy world for Pillars of Eternity. It has the usual recognizable tropes, like swords, shields, dungeons and dragons. Its main appeal though is its peculiar take on souls and mortality.

Souls have been identified as something tangible and workable in the Pillars of Eternity universe, but unlike From Software’s Souls games, they have not been denigrated to the status of a consumable (albeit very precious) resource. They are not treated like playthings for beings that are beyond mortal either, unlike Dungeons & Dragons and to a much worse extent, Warhammer Fantasy. Rather, souls are sacrosanct things, and there are severe consequences and great danger in tampering with them. Even the gods – and there are indeed deities in this fictional universe – think twice about directly messing with souls. (Emphasis on “directly”; gods being gods, they want to mess with souls anyway.)

The current state of the world in this universe is such that souls are being recognized as something worth messing with. The foremost proponent of this is the field of animancy, the latest field of sorcerous science. On the other hand, the manipulation of souls is nothing new; ancient civilizations are believed to have dabbled in such things, and are believed to have perished as a result. Predictably, this leads to a powder-keg situation, made all the more complicated by the hands of the gods (i.e. their mortal champions).

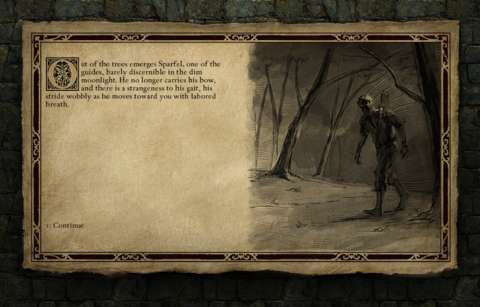

It is into this world that the protagonist is introduced. He/She is a tag-along in a caravan that is going through the particularly dangerous forests of the Dyrwood, which is one of the regions that the game takes place in. (Incidentally, this also acts as the tutorial and prologue.)

Unfortunately, the worst that could happen to anyone in these forests happened; a ravenous storm of spirits ploughed through the caravan, killing just about everyone except the protagonist and two other characters (who will be provisional party members throughout the tutorial).

After another misfortune that killed everyone except the player character, he/she starts having waking dreams, visions and the memories of others, and realizes that his/her sanity is at risk. The only lead that he/she has is a mysterious man that left the scene before this happened.

To describe the story any further would be unnecessary and inappropriate. Suffice to say, the story is woven quite well into the gameplay, typically as an impetus to get the player to move forward. There are side quests that serve as distraction and source of experience points and money, but the main storyline and how it is tied to the backstory of the fictional universe is still the primary appeal of the story-telling in this game.

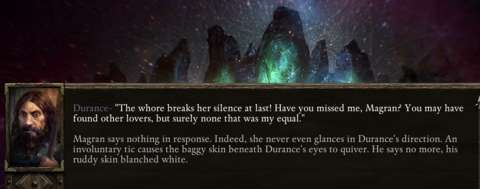

PLAYER CHARACTERS – FOREWORD:

The core of the gameplay revolves around the player characters, including the protagonists. As to be expected of a Western RPG, there is a complex system of mechanisms and statistics that govern their performance in combat and non-combat situations (the latter happens much more often for the protagonist).

Most of the rewards that would come the player’s way are things that bolster player characters, whether it be in the form of loot, gear and other assets, and in the case of the protagonist, his/her reputation.

ATTRIBUTES:

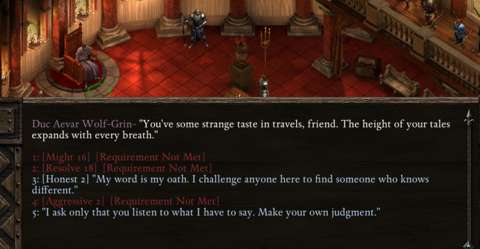

Veterans of Dungeons & Dragons (be it the tabletop version or the video games based on it) would find the statistics known as “attributes” to be all too familiar.

Some of the attributes are the usual mainstays, namely Might (which is of course another name for “Strength”), Dexterity and Constitution. For the sake of the layman who does not know anything about these, these determine a character’s physical capabilities.

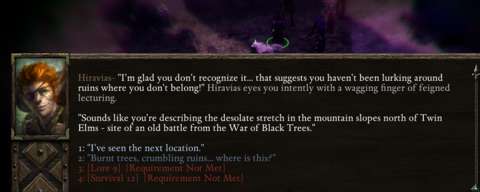

Some attributes have familiar names, but work quite differently from one would expect. For example, there is “Intellect”, which is actually Charisma, Intelligence and Wisdom from Dungeons & Dragons lumped together. “Resolve” is a similar mash-up. They are actually used for different things and different situations. In the case of non-combat situations, which of these two is applied to which situation can be conveniently determined by the literal meaning of these words. Their uses in combat are more arbitrary, but there is in-game documentation that describes this.

“Perception” is perhaps something borrowed from non-fantasy RPG IPs. As in those RPGs, it determines the ability of a character to shoot targets with ranged weapons. Interestingly, it also determines the Reflex rating (more on this later), which is the ability of a character to dodge area effect attacks; in other games, this is usually determined by Agility (or its equivalent) only.

There are plenty of options in non-combat situations that appear when the player has the Attributes to unlock them; the player can enable the feature to show any unavailable options that are associated with these Attributes.

DEFENSE RATINGS:

Defense ratings are statistics that are only ever used for combat purposes. There are four types of defense ratings: Deflection, Reflex, Fortitude and Will. The values of the defense ratings are dependent on their associated Attributes and modifications from gear and spells.

Each defense rating is used against incoming attacks that specifically target the rating. This means that for better efficiency in combat, the player might want to use attacks that target the lowest defense ratings that enemies have.

That said, it seems that these defense ratings are no more complex than as a part of an expanded rock-paper-scissors system. For one, it is peculiar that despite its name, the Reflex rating could not be used for evading melee or ranged attacks.

‘ACCURACY’:

As mentioned earlier, there are attacks that target specific defense ratings. The statistic that determines the reliability of these attacks is known as ‘Accuracy’. For example, all physical weapons have an ‘Accuracy’ rating against Deflection.

Some attacks do not have any modifiers for their ‘Accuracy’, but there are some that have bonuses or penalties for the thresholds of the roll that will be made against the appropriate defense rating. For example, weapons of higher quality have better bonuses to their ‘Accuracy’ ratings.

ATTACK RESOLUTION:

Pillars of Eternity does have a hit-or-miss system for the outcome of attacks. Rather, its system has some nuances that make it much more reliable than the usual chance-to-hit system used in other RNG-dependent games.

Firstly, the Accuracy of an attack and the targeted Defense rating is not used as thresholds for rolls. Rather, the difference between these two statistics is used to shift the entirety of the threshold range for rolls.

To elaborate, the default threshold range is 15% chance for missing, 35% chance for grazes (more on this later) and 50% chance for regular hits. This is the range that is used if the aforementioned difference is zero. There is also no chance for a critical hit, which is a rank above regular hits.

As an example, if the difference is a positive 15, the threshold range is shifted to 0% chance of missing, 35% chance for grazes, 50% chance of regular hits and, most lucratively, 15% of critical hits. This is obviously a vast improvement, there being no chance of missing at all.

In yet another example, if the difference is a negative 50 (which happens if the player is going to places that are far too dangerous for the party), there is no chance of regular hits whatsoever. There is 35% of grazes, and an abysmal 65% of missing altogether.

Perhaps the most important consequence of such a system is that there are no guaranteed ranges for ‘critical’ misses or hits. It also means that if the party greatly overmatches a group of enemies, the party is going to wipe them out in very short order, with no chance of screw-ups due to bad luck at all.

GRAZES & CRITICAL HITS:

Grazes have weaker damage output than regular hits. If the attack has any secondary effects, like inflicting a de-buff with a duration, the duration will be reduced too. Critical hits do the converse.

There are buffs that can improve or demote the type of hit that a landed attack has made. (Emphasis on “landed”; there are very few things, if any at all, that can turn missed attacks into grazes or better.) These buffs can be provided by certain potions, spells and more commonly, gear pieces. These buffs essentially alter the aforementioned threshold range further, albeit section by section, instead of resorting to RNG rolls to decide which attacks are upgraded. For example, the potion of Merciless Gaze folds the upper 15% of the sub-range for regular Hits into the sub-range for Critical Hits.

REAL-TIME COMBAT:

Veterans of the Black Isle games may have the impression that the combat in Pillars of Eternity is based on the so-called “pseudo-real-time” combat of the Infinity Engine games. Although the former does resemble the latter, combat in Pillars of Eternity is real-time.

This can be seen in the application of timed buffs and de-buffs; these have durations measured in seconds, and commence upon their application. They do not work on basis of combat turns like the Infinity Engine games. Even long-term buffs and de-buffs have their durations measured in seconds, albeit in three-digits.

This makes for little to no ambiguity about the factor of time in combat, which is good.

RECOVERY:

Even though combat occurs second-by-second, characters still have a statistic that regulate how frequently that they perform actions. This is “recovery”. It can be difficult to understand at first, due to how rare this system is in the history of video games.

When a character takes an action, there is the time needed for the animation for that action to happen; this is spent time that generally cannot be avoided or reduced. However, each action also comes with another time cost: this is the recovery time, which is measured in units equivalent to seconds. As long as the character is subjected to recovery time, he/she/it cannot perform any other action.

(Running about freezes the countdown of the recovery time, so kiting tactics are not as efficient as one would think.)

By default, every character experiences recovery time by one unit per second; this is his/her/its recovery speed. There appears to be nothing in the game that accelerate recovery speed, which is perhaps a gameplay-balancing design decision.

However, there is a thing that can reduce recovery speed: the weight of the armor that a character is wearing, if any. This reduction in a character’s recovery speed results in longer actual recovery times. There are few things that can reduce this penalty, so the player must keep in mind the trade-off between the protection provided by armor and how much it slows down a character.

Recovery is an elegant gameplay element that brings balance to combat, but its representation in the user interface is perhaps not as elegant. It is represented as a meter that floats above a character’s model, diminishing from full to empty, regardless of the actual recovery time in seconds. It is helpful when there are only a few characters to track, but it is next to useless when there are many characters; in these scenarios, the player is better off looking for another variable as a yardstick for micromanagement, such as characters’ health meters.

ATTACK SPEEDS:

Spellcasters always have more versatility than front-line characters such as Fighters and Paladins, but they are stuck with whatever speeds that their spells have. Front-line characters can change their weapons though, so they are not as stumped.

Different weapons also have different recovery speeds after their attacks, though this statistic is unfortunately not entirely clear to the player. Generally though, lighter one-handed weapons have faster recovery speed than the bigger, two-handed ones.

DAMAGE TYPES & DAMAGE REDUCTION:

Damage Reduction (DR) is the statistic that, obviously, reduces damage from hits that land. There is a DR rating that corresponds to each type of damage, of which there are three overarching groups.

Physical damage types are inflicted by weapons most of the time, but there are magic spells that do this too. Elemental damage types include the usual suspects of non-physical damage like fire, though some of them have slightly different names, such as “Corrode”, which stands in for “acid”.

Raw damage is its own group. This is essentially damage that cannot be diminished by DR ratings. It tends to be inflicted by poisonous and mental attacks, though there are a few damage-over-time effects that inflict it too, such as the Insect Plague spell.

Armor provides the bulk of a humanoid character’s damage reduction. Unless stated otherwise, the damage reduced by armor from any kind of attack is equal to the DR rating of the armor. However, certain pieces of armor have different ratings for different types of damage. For example, plate armor has weaker resistance to Shock damage, which is represented as a percentage penalty for its Shock resistance.

GEAR PIECES:

A humanoid character (called “kith”, in-universe) can wear several types of gear. There is armor, which is gear that anyone should have, even though most armor diminishes the recovery speed of characters.

Next, there are of course weapons. There is the usual fantasy RPG fare, such as swords, axes, spears and bows. However, there are also more interesting medieval weaponry, such as estocs that can bypass some of a target’s DR rating. Furthermore, since the setting of the game includes the advent of gunpowder, there are firearms too.

Wands and sceptres also count as weapons; they are essentially ranged weapons. This is nothing new in video games, but interestingly, they do not inflict elemental or magical damage. Rather, they fire projectiles that either pummel the target or pierce through it, thus inflicting the appropriate physical damage.

Each kith character can wear one ring on each hand. This is just as well, because rings are among some of the most common non-armor accoutrements. Next, there are belts, boots and gloves.

A kith character can wear amulets or capes too, but these two types of items occupy the same slot. This is an odd design decision; having to choose between capes and amulets is unbelievable when humanoid people should have been able to wear both.

There are helmets, but most helmets, if they are not enchanted, are quite useless. Incidentally, there are incredibly few enchanted headgear; what there are, are not particularly powerful. This limitation is perhaps there to balance the fact that the God-like kith cannot wear helmets.

ONE-HANDED AND DUAL-WIELDING:

Although the player will want to make sure that any non-weapon gear slot is filled, he/she might need to be more careful with weapon slots.

One-handed weapons take up only one slot; as long as the other weapon slot is empty, the character gains a bonus to his/her Accuracy.

This bonus is of course lost if the other slot is filled with a weapon; the character gains another attack cycle, but the recovery times do happen to compound and accumulate (though a character that is dual-wielding will always have more attacks than a character that is wielding a single one-handed weapon for any given period of time). Furthermore, there is a penalty to the Accuracy of the attacks made with the second weapon. These differences require some consideration on the part of the player.

SHIELDS:

Shields further increase the Deflection rating of a kith character. The larger shields have higher bonuses, but come with the price of penalties to the Accuracy of all attacks; these penalties represent the difficulty of doing things with one’s hands when a large piece of metal is strapped to one’s arm.

By now, most players would realize that the protection provided by almost any piece of gear comes with the price of being less effective when going on the offense. This means that the player would have to consider having specific party members kitted out to be damage-sponges, and only make use of them in offensive moves after the player has softened enemies with the other characters.

CANNOT CHANGE EQUIPPED GEAR DURING COMBAT:

The player cannot change the weapons of characters during combat. In fact, the characters cannot access anything in their inventory, other than items in their quick-use slots.

Nevertheless, to ensure that the player does have some options for dealing with enemies that are resistant to certain damage types, there are two measures that have been implemented.

One of these measures is the usual weapon grouping, which had been around for a while. A player character can switch from one group of weapons to another, which presumably has different damage types, if the player had been paying attention to this detail.

ALTERNATIVE DAMAGE TYPES FOR WEAPONS:

The other measure is more esoteric, at least in the history of Western RPGs. In most RPGs with damage types, weapons only do one type of damage. In Pillars of Eternity, many weapons have two damage types. The justification for this, according to the game, is pragmatism. For example, swords have pommels in their handles, which can be used to bash enemies with, and the hafts of spears can always be used as a bludgeon. As for magical weapons, like wands, their projectiles can be moulded to either explode on contact with enemies, or drill through them.

Whichever damage type would do more damage on an enemy is the one used for damage calculations; there is no other complication, which is very convenient. However, most weapons with reach, such as bows and firearms, do only one type of damage. Perhaps this is to balance against their advantage of range.

KITH RACE:

As mentioned earlier, the “kith” is the catch-all term for sapient humanoids that can converse in languages, use tools and such. There are the humans, which are of course the staple race in just about any RPG, fantasy or otherwise. In this universe, they are the yardstick for physical strength and strength of will (or to put it more cynically, stubbornness).

Next, there are the other fantasy staples. Dwarfs and elves are there, and they typically do not like each other. (The elves in this game are closer in physique to D&D elves than the Tolkien ones.)

Pillars of Eternity’s facsimile of Tolkien halflings are the Orlans. They have very long ears, are intense in their personalities and often quick – which make them very much Halflings, except for the ears.

A fantasy RPG would not be complete with a race that has particularly large physique, so Pillars of Eternity has the Aumauans. They are also practically merfolk.

Finally, there is the Godlike. Rumored to have been the result of the meddling of the gods (something that is indeed confirmed in the sequel), the Godlike have cranial traits that outright make them stand out from other kith. In Pillars of Eternity’s less-than-nice world, this dooms them to a life of persecution and/or uncomfortable veneration. In-game, they cannot wear headgear, but are compensated with bonuses that no other kith has.

(There are no hybrid races; according to the creators of the game, inter-breeding between kith races is impossible.)

In the narrative of the game, the kith race that a companion character belongs to matters a lot, but the kith race of the player character does not appear to be as significant. There are some dialogue options that concern the protagonist’s species in some situations, but the prejudicial ramifications for some kith options are not fully realized. For example, I have selected the kith race of Death Godlike for my character, but the prejudice against Death Godlike rarely manifested in interactions with other characters (despite how understandably hideous Death Godlike can look).

SPELLS:

A fantasy RPG would not be one without magic being thrown or gesticulated around. Pillars of Eternity follows the system of spells that has been established by D&D. Specifically, there are three schools of spells: priestly miracles, druidic magic and wizardry.

Spells for wizards and druids are learned as they gain character levels; the mix of spells that they would get are predetermined, and often less in variety than those available to wizards. However, among the spells that they have, there is always at least one that is useful for any occasion. Yet, there could have been more differentiation between these two schools of spells.

HOLY RADIANCE:

Priests have a special spell that they can use in every combat encounter, but only once. It is initially not a powerful spell, has limited range and is restricted to being radiated outwards from the priest. However, as the priest gains in levels and nurtures personality quirks that his/her patron deity likes, the spell increases in potency and range.

Compared to the system of spells in D&D, which grant different mixes of spells to priests according to their moral disposition and their deific alignment, this single per-encounter spell can seem rather limited in complexity.

SPIRIT-SHIFTING:

Druids would not be druids if they do not have favoured animal totems, so the ones in this game do. They can change their forms into a humanoid monstrosity that resembles their totem animal, gaining bonuses that are associated with the latter. These forms cannot use any weapons, and any bonuses from armor is also lost. These are replaced with animal hides and claws or other appendages.

In close combat, the animal forms can only ever pummel, stomp, gore and/or shred enemies (though they do benefit from bonuses that contribute to unarmed combat). However, they can still cast spells, which is something that is rare in video game druids.

WIZARDRY & GRIMOIRES:

Wizards can boast about having the greatest repertoire of spells; they can learn many, many spells and keep the knowledge of these in their heads. Yet, they also have the embarrassing limitation of having to cast spells from grimoires (i.e. oversized books). To elaborate, wizard spells draw magic from their user’s souls like other spells do, but they are complex enough to require incantations that are read aloud from written media. (In other words, this is the traditional archetypal spell-casting gobbledygook.)

Each wizard has to have a grimoire, into which his/her spells are scribed. The wizard can only cast spells from that grimoire; to cast other spells, the wizard has to switch to other grimoires. Grimoires occupy their own slots, and are the only items that can be swapped in and out of inventory during combat. However, doing so adds a lot of recovery time, thus stalling the wizard’s ability to contribute to battle.

Therefore, the player might want to think carefully about a wizard’s spell composition before heading into battle (or just reload a game-save before battle). After all, the game does provide the convenience of swapping spells in and out of a grimoire outside of combat without any cost.

Grimoires contain practically complete documentation of spells. Therefore, any competent wizard can obtain another wizard’s grimoire (by any means), and proceed to learn and copy any of the latter’s spells that have been scribed into the grimoire. Gameplay-wise, this happens instantaneously, with the payment of a money fee. Wizards can learn spells when they gain levels too, but copying from others’ grimoires is the quickest way to expand one’s arsenal of wizardry.

FOCUS:

The Cypher is another kind of spell-caster, but unlike other spell-casters, his/her spells are not replenished upon resting. Rather, they are always available, as long as the Cypher has built up the energy to cast them; this energy is called “Focus” in-game, though that is a bit misleading (perhaps deliberately so, narrative-wise).

“Focus” is built up by practically stealing the soulstuff from the fringes of an enemy’s soul (and only enemies; none can be obtained by attacking player characters). This is done by simply attacking enemies with any weapon; the Cypher enchants his/her weapon to do this, as long as he/she can still absorb soulstuff. Speaking of which, there is a limit to how much can be absorbed, though the limit increases as the Cypher gains levels. The Cypher’s default Focus level also increases as he/she gains levels (meaning that his/her opening move in combat can be an increasingly more powerful spell).

Focus that is accumulated in combat can be spent to cast spells. Any accumulated Focus is reset to the default level after a successful battle, but will not dissipate during battle if it is not used.

CHANTING:

The game’s analog of the bard is the Chanter. Like the D&D bard, the Chanter can activate chants (practically songs) that grant benefits to the party. However, the chants only last for several seconds each, and have to be renewed via the “chant” system, which has its own user interface.

A chant is a string of consecutive “phrases”. The trick with chants is that after a phrase ends, its benefits linger for a short while. The chanter begins another phrase, the benefits of which can stack with the lingering benefits of the previous one.

A chanter can have several chants, and can customize each outside of combat. During combat, the chanter can switch between chants readily, but must pay a penalty in recovery time.

A chanter can have several chants, and can customize each outside of combat. During combat, the chanter can switch between chants readily, but must complete the current chant.

Any phrases that have been completed go into a counter that the Chanter can spend for invocations. These invocations tend to be quite tactically valuable, which compensates for the Chanter’s lack of offensive and defensive power. For example, many invocations summon monsters, thus piling pressure on enemies.

It might be tempting to just use short phrases to build up invocations quickly. However, shorter phrases have less potent benefits that becomes progressively less competitive. The longer phrases have powerful buffs that the player might want to keep around, but the chanter would be building up invocations slowly.

Compared to the systems for the other magic-workers, the chanter’s is very interesting to use, though not as readily deployable (even when compared to the Focus system). However, chants do have the advantage of being applied to the entire party, regardless of where party members are.

QUICK-USE ITEMS:

In addition to the gear that a player character has, there are loose consumables that he/she can use. These include potions, scrolls, food and magically-charged baubles. These must be equipped in the quick-use slots before they can be used. That said, this requirement can make these items very cumbersome to use. Nevertheless, these items are powerful enough to give a character a considerable edge. (They will be described later in their own sections.)

PER ENCOUNTER ABILITIES:

All player characters have powerful abilities that can turn the tide of a battle when used at the right time. These powerful abilities may come from their own innate capability or their gear. However, to balance these, these abilities have limited uses per combat encounter. After the combat encounter ends, the number of uses for their abilities resets.

PER REST ABILITIES:

There are abilities that are even more potent and/or versatile than those that are reset per encounter. These include spells and some particularly powerful attacks (such as those that high level Fighters have). Understandably, these are replenished by resting.

MODAL ABILITIES:

Some abilities are used by toggling them on or off. Paladins and Fighters, in particular, have a number of these. After activated, they usually confer some benefits to the player character (or to other party members), but at the expense of the character that activated them. For example, the Fighter can have a modal ability that reduces his/her Deflection rating while increasing the number of enemies that he/she can be engaged with (more on engagements later).

The problem with modal abilities is their opportunity costs. They are often obtained from taking options offered by level-ups, yet there are many other options that are competing for the player’s attention. Furthermore, the usage of some modal abilities is mutually exclusive from the others, such as the Paladin’s (completely beneficial) auras, but they have to be separately obtained from level-ups.

ENGAGEMENT:

There are games that implement gameplay coding that represents the concept of being outnumbered in melee. Then, there are games that have features that allow characters to attack the backs of enemies for extra damage, or “sneak attacks”, to state their colloquial names. Pillars of Eternity is a game that does both, and elegantly so with a single gameplay element instead of two.

There is the system of “Engagement”. A character is “engaged” when it is being attacked by an enemy in close combat. In this case, the character immediately stops moving, if he/she was moving earlier, and has to fend off said enemy.

A character’s limit on Engagement determines how many opponents that he/she/it can lock into close combat. If the character’s Engagement limit is higher than one, any other enemy that moves too close to the character has to stop and fight the character in close combat. In the case of there being more enemies than a character’s Engagement limit, engagement priority is given to enemies that have engaged the character earlier. Any extra enemies can move past the character, if they wish to do so.

Any enemy that has been locked into close combat through the Engagement system is also considered to have used up one unit of its Engagement limit. This means that the player (or the opposing CPU-controlled side) can have his/her own characters moving past enemies that have already been fully engaged.

Most characters can only handle one-on-one engagements, though characters that are meant for frontline combat can engage more than one enemy.

ATTACKS OF OPPORTUNITY:

Characters that are Engaged are not permanently stuck in close combat. They can move away, but this immediately triggers an attack from an opponent that they were engaged with. This is, of course, the game’s take on the “attack of opportunity” system that had been around in RPGs.

For the most part, this works against the player more than it does CPU-controlled enemies. CPU-controlled enemies rarely if not never willingly invite such attacks. Moreover, CPU-controlled enemies are well aware of the Engagement limits that player characters have; expect them to just run past the party’s front-liners after they have been fully engaged, if they can.

FLANKED:

The facing of enemies relative to a character when they are engaged in close combat is important too. If a character is engaged with an enemy and is attacking it, any enemy that happens to engage him/her/it at his/her back will cause the character to suffer the “Flanked” de-buff, which is a considerable reduction in his/her/its Deflection.

The worst problem is that this de-buff enables the character to be struck by Sneak Attacks, which inflict considerable damage. Sneak Attacks can be used against characters with other de-buffs, but the Flanked de-buff is the easiest to inflict on characters as long as they are outnumbered. Incidentally, the player’s party is almost always outnumbered, especially on the higher difficulty settings.

INTERRUPTION:

Having a hit land on oneself is an unpleasant experience that is more than likely to disrupt whatever one is doing. In this game, this concept is represented by the Interrupt system.

Landing hits on characters forces them to make concentration rolls. If they fail their concentration rolls, any action that they are currently undertaking is cancelled; spells fizzle, swings with weapons stop and such other actions that require bodily motion are cut short. They are then subjected to Interruption.

Every attack, be it sourced from a weapon or spell, has an Interrupt rating. Any attack that lands essentially adds its Interrupt time to the target’s recovery time. This can be a source of imbalance, so there are some mitigation measures. For example, weapons that have high attack speeds and low recovery times have very low interrupts.

This gameplay element can increase the complexity of the estimation of the performance of the party against an enemy group and introduce more concerns to combat. For example, the player would have to consider whether to focus on an enemy that has debilitating attacks in order to impede it from crippling the party, or to follow the usual strategy of killing glass cannons first.

POTIONS:

Potions are a staple of fantasy RPGs. The potions in Pillars of Eternity are the positively beneficial kind; very few, if any, of them have deleterious side effects. Potions can be found from a number of sources: loot from cupboards and cabinets, purchases from alchemists and medicine-sellers and products of crafting. A potion used at the right time can be incredibly advantageous.

SCROLLS:

Scrolls hold the power of spells in them, though not the knowledge to learn them. To use a scroll, a character must have the necessary character level and Lore level to use it. More powerful scrolls have higher requirements. Most scrolls have spells that are used by druids, wizards or priests.

Apparently, scrolls are there just in case the party lacks certain spell-casters. For example, a wizard may only cast wizardly spells, but he/she can still use scrolls with spells that his peers in other fields use.

Interestingly, there are some scrolls with spells that druids, priests or wizards do not have. These are the “Rite” spells. Generally, these scrolls increase characters’ attributes or skills, which are considerable bonuses.

BAUBLES:

There are fetishes, magical foci and trinkets that have been invested with powerful spells. Most of them have limited uses, but there are some that refresh their charges after having the party rest.

The main advantage that these items provide is that anyone can use them; they do not require Lore skill to be used. They can be placed in the hands of characters who otherwise have very little overall versatility in combat, such as Fighters and Rangers.

MANY THINGS CANNOT BE USED OUTSIDE OF COMBAT:

Potions, scrolls and baubles cannot be used outside of combat; most spells also cannot be used outside of combat. This is a considerable difference from many Western fantasy RPGs. This means that the player cannot power up the party with buffs before a battle, even if the player can see it coming. Furthermore, any buffs that are sourced from potions, spells, non-Rite scrolls and baubles are lost after a battle. (Fortunately, de-buffs are lost too.)

Perhaps this was intended for the purpose of gameplay balance. The player will need to decide whether to have the party spend their first few seconds buffing themselves up, or doing something to harm or impede the opposition.

Nevertheless, the player does have some options for pre-battle buffing. For example, Rite scrolls can be used outside of battle. Food, drinks and drugs can also be used outside of battle too, though only food is positively beneficial.

FOOD:

Foods are consumables that generally grant bonuses to attributes (with the exception of Intellect) and Endurance (more on this later). Food does not spoil and they have considerably long durations that last beyond the end of a battle. The player can also stack buffs from different types of food. However, the ingredients for food are generally only ever bought from hawkers, or found in kitchens or the warehouses of civilized places.

CRAFTING:

There is a rudimentary system of crafting in this game. The player can gather ingredients and materials that are needed in recipes from many sources, loot from enemies being the most abundant. All recipes for items that can be crafted are available from the start. These items are consumables, namely potions, scrolls and food.

Conveniently, crafting can be done at any time and anywhere. Crafting is instantaneous too. The player only needs to meet the ingredient and material requirements. Ingredients and materials never spoil too, and they are stored in the stash section of the player’s inventory (more on this later).

All these advantages greatly encourage the use of crafting. However, as mentioned earlier, many things cannot be used outside of battle, so having lots of consumables is not always useful.

DRINKS & DRUGS:

The world of Pillars of Eternity is not one without hard vices. There is plenty of strong drink, and a considerable number of substances that can be abused.

Drinks and drugs grant considerable bonuses for an incredibly long time (600 seconds); they last beyond the end of battles too. Some of these can be useful, such as the drug that makes its user immune to the Confused de-buff. However, as soon as their effects end, their users are struck with equally long-lasting de-buffs. The de-buffs can be removed by consuming the drinks or drugs again, but of course, this is not sustainable in the long term.

STASH:

One of the most significant problems – and complaints – about Western RPGs on the computer platform is that the player’s inventory of items is only limited to whatever the party of player characters can only carry. Although this is an understandable limitation, it hurts any attempt by game designers to diversify the gear that player characters can use. More diversity requires more items, which the party cannot hold, or it requires more complex gear that can be reset to have different functions, which meant more complicated coding (which also means more bugs).

Therefore, Obsidian addressed this issue by simply having a stash of stuff that the player can access at any time outside of combat. This is unbelievable, but very convenient.

The stash is not without problems though. The stash is already implemented in the inventory user interface as a tab, so there are few means to navigate through the stock of items that the player has, other than the filter tools.

ENCHANTMENT:

In the world of Pillars of Eternity, soulstuff is strong enough to persist even in supposedly inanimate objects, provided that it has been moulded properly for infusion into objects. Of course, this is not much more different from the fantasy trope of making objects magical.

Although the lore of the game suggests that enchantment is an elaborate process that has to be done by dedicated professional enchanters, the player is given some readily available options for enchanting items. However, these options are limited to just armor pieces and weapons; other items cannot be enchanted at all. Nonetheless, armor and – especially – weapons will be among the player’s most utilized gear, so these options are still likely to be useful to any player.

Enchantment is a mostly irreversible process, however. Some enchantments can be overridden, such as the quality of an item, but the player is not reimbursed for any costs of the previous enchantment. Therefore, the player will want to be careful in his/her decisions. Besides, the ingredients for enchantments, especially the high-end ones like dragon organs, are limited in supply.

In addition, an item can only have so many enchantments; this is represented by enchantment ‘slots’. More powerful enchantments generally consume more slots. Furthermore, unique items already have special enchantments that occupy some slots. Speaking of which, the costs to enchant unique items further are noticeably higher than the costs for enchanting originally mundane items.

Moreover, useful general-purpose enchantments cost more than those with situational uses. For example, bonus damage against kith costs a lot; this is understandable because kith enemies are prevalent throughout the game.

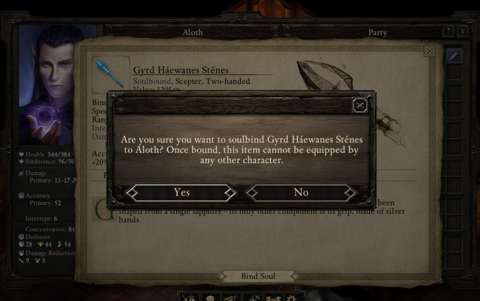

SOUL-BOUND ITEMS:

Some items are not improved through enchantment. Rather, they already have enchantments of their own, but require soulstuff from their wearers/wielders. This soulstuff is provided through the accomplishment of specific tasks performed by their wearers/wielders, who first have to be “bound” to these items.

This is a combination of two systems that had been around in the history of Western-made RPGs: the system that binds items to specific named characters (originally meant to prevent item-trading in games with multiplayer aspects) and a system that applies a progression scheme for items, much like those for characters. In Pillars of Eternity, this is used to balance against the emergent power of these items, which are considerable.

As each task demanded by a soul-bound item is completed, it unlocks one or more of its latent power. In the case of weapons and armor, this almost always includes an increase in their item quality. There are other properties too, and these happen to make them far more powerful than even unique items. For example, there is a sceptre that can inflict debilitating de-buffs on enemies that its projectiles hit. For another example, there is a hat that inflicts de-buffs on enemies that hit its wearer.

However, the player has to doubly make sure that the item is useful to the character that is bound to it. The binding can be severed without consequences for the character, but any magic that has been unlocked for the item is sealed away again.

(This gameplay element was actually introduced in the first White March expansion, but it was also added to the base game upon the release of the second expansion. A free DLC package of the game added more Soul-bound items. Therefore, it is described in this review article instead of the articles for the expansions.)

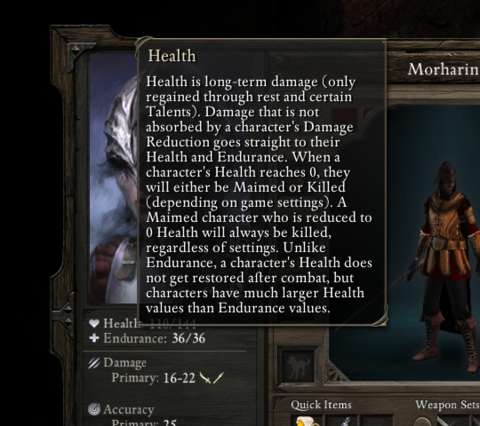

HEALTH AND ENDURANCE:

Interestingly, instead of using a system of hitpoints, Pillars of Eternity uses two layers of durability for player characters. Endurance is the statistic that comes into play in combat; soft-bodied player characters can rarely have more than 200 points of it even at high levels, but front-liners can have more than that. Any damage that is inflicted on a player character goes to reducing Endurance; the damage is also duplicated and this goes to reducing Health. Player characters have much more Health than they do Endurance.

The emphasis here is that only player characters have health; enemies only have Endurance.

During combat, if a player character loses all Endurance, he/she is knocked out and goes unconscious. The model of the player character is still there, and can be hit with area-effect attacks for damage that goes straight to reducing Health. However, they are practically rendered invisible to enemies, who will ignore them and go after any remaining player characters that they can detect. As for enemies who lost all of their Endurance, they are simply dead.

WOUNDS:

The Cypher is not the only character with a unique gameplay system; the Monk is another. Where the Cypher gains energy to do his/her thing by hurting enemies, the Monk gains energy by being hurt. However, the Monk’s Wound system is a bit more complex.

Any nett damage that the Monk took after getting hit goes to a counter. After the threshold for this counter has been breached, the Monk gains one point of Wounds. Wounds activate some of the Monk’s passive abilities, and can be spent to activate some active abilities (usually to return the hurt to enemies, with plenty of interest).

However, unlike Focus, Wounds will dissipate one by one during battle, usually after a few dozen seconds (there is a tracker for each separate point of Wounds). This is perhaps for the purpose of gameplay balance.

REVIVING AFTER BATTLE:

If the player wins a battle and no other enemies enter the fray, the Endurance of all player characters regenerates rapidly. If their Health level is still higher than their maximum Endurance level, their Endurance returns to full. Otherwise, their Endurance is limited to their current Health level; the user interface will conveniently display this. Having the Endurance of one or more player characters curtailed by low Health is a cue that the player might want to have them rest.

This limitation is there to address the abuse of healing spells that are prevalent in Western RPGs, while allowing the player some leeway in having the party continue their adventuring after a nasty battle.

INJURIES:

Player characters that have been downed will revive too, but they will sustain semi-permanent injuries that can only be removed by resting. These injuries are debilitating; if they happen to severely gimp a player character’s performance, the player might want to have the party rest, even if it is just one person.

MAIMING AND DEATH:

On lesser difficulty settings, losing all Health does not immediately result in death for a player character. The player character is Maimed instead, suffering considerable penalties to their performance. This is very much a cue for the player to have the party rest.

If the player persists anyway, the Maimed character becomes a liability; he/she will have next to no Endurance and Health, and will go down in just one hit. This hit will kill them dead, certainly so on the higher difficulty settings. The death of player characters means that the player loses the opportunity to pursue their personal quests or any assistance that they might provide in certain situations.

It is very difficult to end up with such a situation without deliberately putting player characters in the fire, so the player very much deserves this setback. (Of course, the player could just reload a game-save if he/she is not playing on Trial of Iron mode.)

HITTING PLAYER CHARACTERS:

A player character can hit other player characters, unwittingly or deliberately (depending on the player’s decisions). Most of these cases involve the use of spells with area-effects that do not discriminate between friend and foe. Such occurrences also evince amusing remarks from player characters that are hit, e.g. Pallegina curses in Vailian.

There are generally few reasons to deliberately attack player characters. Focus and Wounds cannot be obtained this way. Some tasks to empower Soul-bound items cannot be fulfilled this way too. The developers have certainly thought of preventing such exploits.

However, amusingly, some characters can deliberately hit player characters to impart some benefit. Chief of these is the Paladin, who can hit player characters that are under the effects of mental subversion to immediately cancel the de-buffs.

(Incidentally, this ability of the Paladin is the fastest way to cancel such de-buffs; spells that counter de-buffs only temporarily suppress them.)

Interestingly, all area-effect spells have two radii. The outermost radius is the reach of the spell that is applicable to enemies, whereas the inner radius is where the spell affects both enemies and player characters.

EXPERIENCE SCALING:

Experience points are awarded through many means. Some experience rewards are scaled according to things other than the party’s average level. For example, disarming traps and unlocking things grant experience points that are scaled according to the difficulty of the obstacles. Some other experience rewards are scaled according to the player characters’ levels, such as the experience points from completing quests.

RESTING:

Resting resets the party’s condition completely; even maiming and injuries can be removed with 8 hours of rest. (Of course, presumably, the party focuses its attentions on addressing these problems.) Another incentive to rest is that certain long-term bonuses can be obtained through resting.

Resting can be done in one of three ways: the first is resting with campfires. The party must have camping supplies in order to do this; the maximum amount of supplies that the player can have is determined by the difficulty setting. The range of options for bonuses that are obtained from campfire rests is determined by the player characters’ Survival skills; any character that lacks this skill or is bad at it has very limited options, if any at all. Moreover, the bonuses from this kind of resting only last in between campfire rests; they are overridden by the bonuses from the next campfire rest. However, these bonuses do stack with the bonuses from other forms of resting.

Then, there is paid-for resting at inns. Each inn has its own set of options for bonuses; better bonuses typically have higher fees. Inns usually appear in settlements and places of civilization, which is just as well because the player is prevented from setting up campfires in these places. The bonuses from resting at inns last for a few campfire rests, but does not stack with the bonuses from resting at the stronghold.

Speaking of which, after the player has obtained the stronghold (which is the keep of Caed Nua), the party can rest at the stronghold and gain one of the bonuses from the buildings that the player have restored. These are potent bonuses, more so than even the glitziest of inns, but this comes at the price of having to travel to the stronghold, which just seems to be one day worth of travel from anywhere.

TRAPS AND TEDIOUSNESS:

As to be expected of a Western fantasy RPG, there are traps strewn about in dungeons and lairs. They await the unwary, springing when careless fools step on their triggers. The punishment that they can inflict varies, from small sharp darts to petrification spells. (There do not seem to be any massive traps such as crushing walls and rolling boulders though.)

Traps have delayed triggers, but always make attacks against whoever triggered them, or center their area of effect on the victim, if they are the kind that affects an area. The keyword here is “attack”; traps do not automatically hit their victims, and will need to make rolls against the latter’s Defense Rating, whichever appropriate.

Player characters that have invested points into their Mechanics are able to spot them; they are more capable at doing so if they are in Scout mode (more on this shortly). Any discovered traps can be disarmed, if there is a character capable of disarming them. Failure to disarm traps does not trigger the traps; they just remain where they are. However, player characters will not automatically avoid traps.

Disarmed traps are recovered intact and go into the inventory, ready to be reused. The player can also purchase traps for use.

Unfortunately, there are plenty of limitations that gimp the use of traps against enemies. The first and worst of these is that each player character can only place one trap; attempting to place another causes the previous one to be removed and returned to inventory. It can be very dissatisfying that the player character that had been clearing entire corridors of traps can only ever lay down one trap.

The second is that any trap placed by a player character has a trigger zone that can only encompass the space of a doorway. Without the use of chokepoints (such as doorways) or at the very least, turns around corners, traps are next to useless.

The third is that many traps have inherent penalties against the Accuracy rolls that they make against the victim’s Defense Rating. To offset these penalties, the player character needs to have a high Mechanic skill, which can reduce the penalties and perhaps even boost the rolls. Unfortunately, this also means that player characters that are lousy at Mechanics will be placing traps that are flawed.

These limitations are not completely described in the in-game documentation.

There had been other games that did traps better, such as (overall inferior) Neverwinter Nights series, which allowed the player to easily hotkey trap-setting, did not limit trap setting and have much more generous trap-triggering zones. Perhaps all the limitations on traps in Pillars of Eternity is intended for gameplay balance, but they also make them tedious to use.

LOCKPICKING:

The other use of Mechanics is to pick open locks. Unlike the system for traps, the system for Lockpicking is much more generous.

Every lock has four levels of difficulty, represented by the levels of Mechanics that are needed to deal with it. If the player character has a Mechanics rating that is far above these levels or at least matching the highest level, the lock can be picked open easily without a fuss. For the other three levels, the player character with Mechanics ratings matching them has to use and consume lock-picks; the lowest level requires three of these. They are cheap to buy, but they are sold in small numbers and are not easy to find elsewhere.

Picking a lock happens to grant some experience points, but opening locks with keys that match them do not. The player has to pick between expedience and pedantic experience min-maxing, but the amount of experience granted is small enough to make the decision easy.

SCOUT MODE:

Every player character can go into Scouting mode. This is very much a convenient combination of sneaking and searching.

One purpose of this mode is to search for traps; even characters with lousy Mechanics will eventually spot traps, given enough time.

The other purpose is to sneak around. Thankfully, Pillars of Eternity uses a deterministic system for this. An eye-shaped icon appears under the player character that is sneaking around. This icon fills up when the player character is within proximity of NPCs and/or within their view cones (which are not shown, unfortunately); NPCs that have better perception will cause the icon to fill faster. Once it is filled, the icon turns red, indicating that the player character has been detected.

The Stealth skill of the player character is the main determinant in how good he/she is at sneaking. Interestingly, the equipment of player characters does not inherently hamper their stealth, unless explicitly stated to do so. Even a player character that is wearing plate mail, chain mail or stupidly brightly coloured robes can sneak around, as long as what they have does not penalize stealth outright.

There are some scenarios where stealth might be helpful, such as having a sneaky player character bypass some groups of enemies and finding the switch that would open a door or lower a wall that lets the rest of the party reunite with the player character. However, these scenarios are far and few in between. It might even be in the player’s interest to plough through enemies instead.

HIDDEN THINGS:

Traps can be found given enough time, but hidden treasure and switches will remain undiscovered until there is a player character with high enough Perception or high enough Mechanics to spot them, whichever requirement is met first. Usually, the player’s rewards is extra loot (and sometimes very good gear) or a shortcut.

EXPERIENCE DISTRIBUTION:

Whenever the player is rewarded with experience points, the points are distributed to all player characters, including those that are not in the party at the time. However, the latter gets subtly smaller portions; this becomes noticeable if there had been a character that the player has not been using for a long time. This also means that the main protagonist is always the most experienced, by virtue of always being in the party all the time.

(USELESS) PETS:

The player character has a gear slot that is unique to just him/her. This slot is used to “equip” pet items. Upon doing so, a small-sized NPC appears in the game world and follows the player character around, often at an unsettlingly (but hilariously comical) fast pace. Pets cannot be harmed and do not contribute to combat in any way.

Unfortunately, the presence of pets is not entirely cosmetic. Pets can actually open doors, which can be a problem if the player character is the main sneaker in the party. Pets also have collision boxes, which means that they can get in the way during combat. They are also a problem during exploration, because they do not follow the pathfinding scripts for controllable player characters.

(As a side note, Obsidian does recognize these complaints. Its first step is to introduce a certain “pet” in the first White March expansion. This will be described in another review article.)

PATH-FINDING:

Prior to this game, Obsidian has a history of making games with awful pathfinding for any character, whether human-controlled or CPU-controlled. The player has to hold their hands all the time, during combat and outside of combat.

In Pillars of Eternity, or at least its latest version (2018 at this time of writing, some time after the release of the sequel), the pathfinding of characters is substantially better.

This can be seen in the movement of the party outside of combat. Their models will slow down or accelerate their movement (regardless of any movement modifiers) so that they smoothly pile into a one-icon-wide string that snakes through the map. Furthermore, outside of combat, player characters push away other player characters, if they are ordered to move through them.

Yet, there are still some shortfalls. If a fight is occurring in tight places, which is likely most of the time if the player makes use of chokepoints, the pathfinding of close-combat characters often fails; if they cannot get to their target, they simply stand around, at least until the next “tick” of time when their pathfinding scripts trigger again.

TRAVELLING:

One tribute that Pillars of Eternity makes to the old D&D Infinity Engine games is the lapse of time when travelling from one place to another. It is not entirely clear what kind of travelling method that the party uses, but time will pass when they move from one place to another (barring coding oversights on the part of the developers). The passing of time would not have mattered much, but it does due to the gameplay element that is the stronghold.

STRONGHOLD – FOREWORD:

Ever since Black Isle raised the idea of a staging area for the party in Baldur’s Gate II: Throne of Bhaal, there had been demand among followers of Western fantasy RPGs for similar things. Before this game, the delivery of such a system had been spotty: strongholds, such as the one in Neverwinter Nights 2, give the impression of being watered down in complexity, and do not matter much to the overall gameplay.

The stronghold in Pillars of Eternity is almost a similar disappointment too, if not for its association with some gameplay content that could not be experienced without some attention to the stronghold’s development.

STRONGHOLD BUILDINGS:

The greatest contribution that the stronghold makes to the gameplay is the buildings in it. After restoring them and staffing them, the buildings provide potent long-term resting bonuses. In fact, the player would be spoilt for choices because there are many facilities and buildings that provide these.

Many of these buildings also have vendors staffing them. There are plenty of other vendors, but the vendors at the stronghold happen to more variety in their wares than most other vendors, especially consumables. Having vendors at the stronghold also helps the player in pursuing the story-line about the dungeons and lairs under the stronghold.

NO TELEPORTING TO STRONGHOLD:

There will not be any option to quickly travel to the stronghold, at least not without using the travelling system (which guarantees that in-game time will lapse). Perhaps this was intended to put more emphasis on returning to the stronghold in time to handle matters at the stronghold.

NOTICEABLE LACK OF NPCS IN STRONGHOLD COURTYARD:

As the player invests more in restoring the stronghold, the artwork for the stronghold changes; ruined buildings become pristine again and the grass in the courtyard of the stronghold looks better kempt. However, there is a noticeable absence of NPCs in the courtyard. For example, there is the absence of groundskeepers and soldiers who should be training at the training grounds.

This makes the stronghold just as lively as a piece of still-art. Many other locales are much more vibrant, if only because there are NPCs around to remind the player that they are populated areas. The disparity also gives the impression that the stronghold did not get as much attention from the developers. This can result in a lack of satisfaction from having invested in the stronghold.

PRESTIGE AND SECURITY:

Prior to the arrival of the main player character, the stronghold had fallen on hard times due to neglect. After claiming it, the player can restore it so that its reputation and economic performance are rebuilt. These are represented by two variables: “prestige” and “security”.

Prestige is the main indicator of the income that is flowing into the stronghold (and the party’s account) from the collection of taxes, especially from trade and traffic. As the stronghold’s facilities are improved, its prestige increases.

Security is how well the stronghold performs at securing the aforementioned revenue, and keeping prisoners in (more on this shortly). There are bandits that will always be attacking or pilfering from the tax collectors, resulting in loss of income; this income cannot be recovered in any way and there is no opportunity to hunt down whoever stole it. (Having higher security reduces the money that is lost to banditry, but never completely.)

After having reached certain levels of prestige and security, the stronghold unlocks game content that would not be available through other ways.

STRONGHOLD PETITIONERS:

Some of said content are problems and quests put forth by petitioners that travelled to the stronghold. The petitioners will stay at the stronghold for about a week, during which the party can return so as to entertain their requests, which are often about favours that the player can do for them. Failure to entertain their requests in time means that they leave, but there is usually no further consequence.

Entertaining their requests plays out as a dialogue. Eventually, the player has to choose from one of several options, though the option to send the petitioners away is always there (but there are often consequences for having wasted their time).

These options can result in permanent changes to the stronghold’s prestige and security, so the player will want to choose wisely (i.e. check wikis) in order to avoid wasting the prestige and security improvements from having restored buildings. There are also options that can hurt the player’s holdings, in return for short-term gains or simply to assuage the player’s role-playing desires, if the player is that kind of person. The role-playing options, more often than not, screw over the petitioners and require the assignment of actual party members, which renders them unavailable for inclusion in the party for a few days.

The results of any option are not always immediately known and applied to the player’s holdings. At least several in-game days have to pass before the full consequences are known (though they are always for certain; there is no randomization).

STRONGHOLD ASSIGNMENTS:

Sometimes, other people merely contact the stronghold with messengers and ask for help with problems that happen away from the stronghold. The player can decide to ignore them, or send a party member to deal with the matter. It is in the player’s interest to do the latter; there are rewards that cannot be obtained elsewhere, such as baubles that are charged with powerful spells.

If the player decides to send a party member, he/she will be unusable for a while, but any party member will do; he/she will get the job done. After the job is done, the player is treated to passages about the resolution of the quest. The player is also informed about the rewards, one of which is always a 25% experience boost. (The 25% is 25% of the experience threshold that is needed to level up; all characters obtain them.)

STRONGHOLD TASKS (OR NUISANCES):

Occasionally, the player gets requests from others that are neither petitions or assignments; these are just nuisances instead. These will hurt the stronghold’s Prestige or Security if the player does not respond to them. Responding to them is nothing more than a resource sink or a tying-up of a party member too.

VISITORS TO STRONGHOLD:

There are some stronghold events that the player has little control over: these are visits by prominent people. Fortunately, these are mostly beneficial to the stronghold. For example, one of the visitors could be a wealthy merchant that has been rescued from a bandit attack; the merchant repays the favour by speaking good things about the stronghold for a while, thus temporarily increasing the Prestige of the stronghold.

STRONGHOLD TREASURY LOOTBOX:

Some of the stronghold’s buildings generate resources daily; these are ingredients that the player can use for crafting consumables. However, these do not immediately enter the player’s stash. Instead, they are kept in a chest at the stronghold. This is, of course, another incentive to regularly return to the stronghold. The rewards from assignments are also placed in the chest.

ATTACKS ON STRONGHOLD:

No thanks to the relative lawlessness of the unsettled regions around the keep and the threats from underneath the stronghold, the stronghold is always subjected to the risk of being attacked. Conveniently though, the player is always warned about impending attacks one week away; this gives the player time to confront the attackers. Failure to do so means that the keep gets attacked, and damage might be inflicted. In particular, some buildings can end up being destroyed. (This also removes any Prestige and/or Security bonuses that they provide.)

Confronting them is not an easy matter either. The party is usually placed in one of two places in the stronghold: the main hall of the keep, or the grounds of the keep just outside the main hall. Neither places are great, because they are open. The opposition might also outnumber the party.

Fortunately, the player is informed of the type of enemies that are attacking, so the player could make some preparations. For example, if the player is facing enemies that rely on making their opponents confused, the player might want to have the party ingesting the drug that renders them immune to the Confused de-buff.

However, the enemies that are attacking are not always scaled according to the party’s level of experience. They may be push-overs that can be wiped out in under half a minute, or they can doom the party right from the get-go. Again, the composition of the enemy is a telling detail; for example, if the player is facing vithrack forces, the player might want to reconsider a confrontation; these monsters are particularly capable of dumping a lot of de-buffs that take the player’s control away.

PRISONERS:

At certain moments in a playthrough, especially during side-quests and encounters that are not listed as quests, the player might defeat some enemies, who then clearly plead for mercy. These are occasions that allow the player to obtain prisoners for incarceration at the stronghold.

When NPCs become prisoners, they effectively lose whatever personality or backstory that they originally have. They become nothing more than just NPCs with prisoner scripts, saying similar things (usually about how they would like to be released) whenever the player talks to them.

Prisoners are security liabilities as long as they remain in the stronghold’s dungeon. They will try to escape, and if they are successful, they might cause damage to the stronghold.

On the other hand, if the player can hold onto them long enough, other people eventually come over to pay the ransom for their release. Releasing them is as simple as clicking a button. (Occasionally, the player could sell prisoners to slave traders, though this can harm the stronghold’s Prestige.)

Overall, this gameplay element is underwhelming. One would think that there could have been more significant uses for prisoners, such as using them for some non-stronghold quests, but there is none. There are so many lost opportunities here.

PASSAGE OF TIME AT THE STRONGHOLD:

Some things in the stronghold, like the expiration of opportunities for quests, the presence of petitioners, and the generation of ingredients, are subjected to the passing of regular in-game time. The occurrence of impending attacks on the stronghold is also subjected to this.

The other things, such as income flows and completion of assignments, are not subjected to the same schema of time. As a rule of thumb, these other things bring money into the player’s coffers, such as the income from collected taxes.

These other things only progress upon the completion of quests, or the completion of a significant phase of a quest; each of these occurrences is called a “turn” in-game. The player will see other notifications appearing on-screen when a quest or quest phase has been completed.

HIRING NPCS TO DEFEND THE STRONGHOLD:

Having to return to the stronghold to fend off attacks can get old quite quickly. Fortunately, there is the choice of hiring NPCs to defend the stronghold. The player can only have eight of them, but all of them will be committed to a battle against attackers; that would be eight characters, compared with six from the player’s party. Of course, the player cannot control them, and the outcome is determined by RNGs.

Some of the NPCs have modifiers to the stronghold’s Prestige and Security. Some of them are beneficial, such as if they are reputable guards and mercenaries. Some give penalties, such as if they are an ogre that the player can hire after some careful diplomacy with it; ogres might be sapient, but they are sociopathic and often of hostile temperament.

NPCs can die, however. In the case of named NPCs, they are lost if they are killed.

VENDORS:

There are plenty of merchants, shopkeepers, stall-owners and other vendors. Obviously, they are there so that the player can sell and buy stuff.

The user interface for buying and selling stuff is a variation of the UI for the inventory screen, for better or worse. There are filters, but not more tabs. At the very least, there are more icons on the right side of the UI, one of which is the icon for accessing the stash.

However, there is no way to arrange the inventory of a vendor, like the player could with his/her own inventory. This becomes a problem after the player has sold things to the vendor, because these things also appear in his/her/its inventory, making it more difficult to find things that the vendor originally sold.

Fortunately, there is a work-around for this problem, thanks to the convenience of being able to sell anything to any vendor at any amount. The player can sell things that a vendor does not usually sell, e.g. selling weapons to a food vendor, and then use the filters to sift through things.

RETRAINING:

One convenient but narratively awkward feature that inns and the stronghold provide is the retraining of player characters. For a fee that becomes greater as a player character increases in levels, the player character can be completely re-tooled to however the player likes. Of course, if the player has been planning the development of a party character and is committing to that plan, this feature would be used much, if at all.

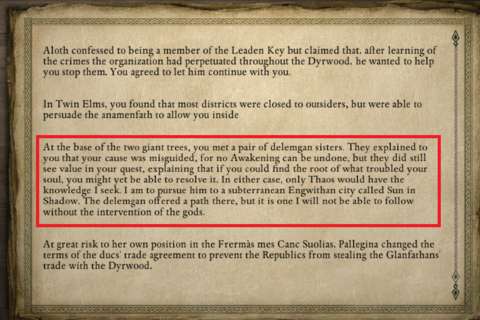

TERTIARY PLAYER CHARACTERS:

Although there are more named and storied party members than there are slots in the party, they might not be enough for the player’s wants and desires. Furthermore, when the player begins a playthrough, the party is understaffed, if the player is using only named and storied party members.

Therefore, there is the convenience of hiring player characters that are practically story extras; this can be done at inns. They do not contribute to the storytelling and do not have quest-lines of their own. Yet, if the player desires effective party synergy and performance min-maxing more than good story-telling, there is this option.

ENEMIES:

A Western fantasy RPG would not be one if the player does not have to fight hostile characters. After all, many abilities and statistics of any player character are relevant to battle and little else.

Some characters, such as angry spirits and hungry wildlife, are inherently hostile to the player’s party. Some others, especially if they are involved in quests, can become hostile if the player antagonizes them. Of course, non-hostile NPCs become hostile if the player hurts them, deliberately or accidentally. Hostile characters can never be ameliorated, outside of scripted events; they are out for the party’s blood, and there is no choice other than to put them down.

Enemies that have been killed generally cannot return in any way; there does not seem to be any spell that can revive enemies. Besides, the icons under their models simply disappear and their models are rendered to little more than props.

(However, enemies that happen to be animal companions of other enemies are merely knocked out when their Endurance is reduced to zero. They can be revived if their friends have the ability to revive animal companions.)

KITING:

Enemies have different movement speeds, and player characters can have their movement speed boosted to considerable levels (or they may already be fast in the first place, such as the smaller animal companions of rangers). Therefore, the player can resort to the tactic of having the party move away from enemies; faster enemies can then be fought piece-meal, or if the enemies are slow enough, they can be shot at while the party avoids close combat with them.

Of course, there is the risk that the party might run into other enemies that are patrolling around if they have been moving about. There is also the limitation about recovery times being frozen while the player characters are moving about.

TRAPPED IN COMBAT BY PROXIMITY OF DOWNED CHARACTERS TO ENEMIES:

The player could break out of combat by having the party run sufficiently far away from enemies if they can (preferably to places where enemies have been cleared out). Enemies will not pursue the player characters once past certain distances from the places where they originally were (unless they have been programmed to continue pursuit).

However, if a player character has been knocked out close to where they were originally were, combat will not end; the player must defeat the enemies and clear out the area around the downed player character for this to happen.

This can be exploited by a reckless player though. If the surviving player characters are still under the effects of powerful spells and potions (especially potions) and/or have a Cypher with a lot of Focus, the player could have them attack the next group of enemies and crush the latter while the benefits are still in effect. Of course, the player is at a disadvantage of having less player characters to deal with these other enemies.

CHOKING:

The player’s most effective tactic against enemies, especially at higher difficulty levels, is to use chokepoints. Most enemies will just pile up in front of the chokepoint, if there are no means to flank the player’s party in the immediate vicinity. This allows the player to efficiently use area-effect spells to ruin them without retaliation. On the other hand, kith enemies could have ranged weapons and will switch over to them if they cannot engage in close combat.

NO CLEAR INDICATOR OF HOW STRONG KITH ENEMIES ARE:

The bestiary helps in gauging the power of non-kith enemies, but there is no way to know how powerful kith enemies are. This can result in some unpleasant combat encounters, especially for groups of hostiles that spawn in a previously visited area after certain conditions have been met. This is particularly the case for bounty targets and their minions, but at least these came with warnings. There are encounters with particularly tough brigands and such others that can result in the player reloading a game-save.

NO EXPERIENCE FROM KILLING ENEMIES:

Unlike the old Infinity Engine titles, defeating individual enemies does not grant any experience points at all; the only exception to this is the first several encounters with previously unseen monsters (this will be described later), but the experience rewards from these are limited.

Therefore, the player might want to consider peaceful or stealthy means of dealing with hostile characters, if there are any such means. However, loot from defeated enemies remains an incentive to be bloodthirsty.

TEXT ADVENTURE MOMENTS:

There are moments in the game when a different UI screen takes over. This is the interface that is used for the text-based adventure moments. In particular, it appears when the party comes across obstacles and physical hazards like large rocks, cave-ins, vine growths and such.

If the player has the means for them, the player sees the options for dealing with these impediments. One of these options might be very dangerous, but does not require more than RNG rolls against the attributes of party members. Success means that they bypass or overcome the obstacles without a problem; failure means that they suffer Injury de-buffs.