INTRO:

Studio Ghibli has a long history of anime production. However, few, if any, of their IPs have been adapted for video game products. In the years before this game, Studio Ghibli is little-caring for video games, is oblivious of them or is cautious about putting a foot in the video game scene. That said, this game stirred much hype due to the news of collaboration alone.

That said, Studio Ghibli’s partner is Level 5, a game developer with a history that is not as long as most other high-profile Japanese companies. However, its history is a dense one, filled with participation from visionaries with track records of realizing good ideas.

The result is a game that is notable for both its presentation and gameplay, but also notable for when either company’s efforts do not mesh and for lessons that Level 5 had yet to learn.

PREMISE:

The story begins in a manner that is more in-line with Level 5’s style. There is a tense scene that shows the wondrous fantastical setting, which is then followed by a flashback to the actual prologue.

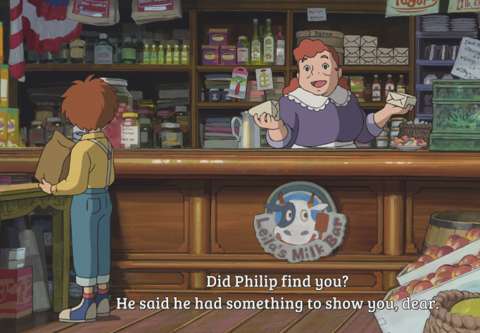

The prologue takes place in what is presumably an American town, possibly in mid-western USA because of the presence of farm produce from Idaho. The era appears to be within the first half of the early 20th century, due to the presence of cars from that era and the prevalence of suspenders in clothing.

Anyway, Oliver is a boy living with his single mum. He would have lived an unassuming life, if not for an event that would be a turning point. A mishap with the car that his friend built led to him nearly drowning in a river. His mother rescued him, but she later died from a heart complication that the ordeal exacerbated. Meanwhile, other scenes show that this was no mere accident; beings from another realm had tampered with events in Oliver’s world to attempt his demise.

In Oliver’s grief, he breaks the curse on a doll that his mother gave to him. The doll comes to life and introduces himself as “Drippy”, one of the most prominent fairies in his world. Drippy tells Oliver about a “chosen one” story, and convinces the latter to go over to his world by telling him that there may be a way to save his mother.

Thus, Oliver goes off to discover another world, determined to somehow bring his mother back to life with magic. However, he will not do so unopposed, because the other world is being oppressed by the aforementioned beings who will not suffer an upstart hero.

ADAPTATION FROM TOUCH-SCREEN CONTROLS:

The original version of the game debuted on the Nintendo DS. There were control inputs that required the use of the touch-screen and tracing of lines. This is a control schema that cannot be translated onto other platforms, at least not without incurring complaints that they are frivolous.

(Indeed, if such schema had been implemented anyway in the computer version of the game, they would have brought back memories of Peter Molyneux’s Black & White titles. Those games were notorious for having line-tracing control schema that does not contribute much to the gameplay.)

Thus, the schema was replaced with button-based controls and context-sensitive scripting when the game was ported over to the console platforms. This is also the case for the “Remastered” version of the game.

THE MUNDANE WORLD:

The gameplay begins with Oliver’s world, specifically his hometown, Motorville. The town setting is something that followers of Ghibli’s works would recognize; the setting is reminiscent of Ponyo and Kiki’s Delivery Service. The eventual introduction of magic would only reinforce this impression.

However, observant players who are long-time game consumers might notice some problems immediately. Firstly, the player does not appear to have any controls over the camera in the mundane world. The camera is set above the town, at an isometric angle. This means that Oliver and NPCs can be obscured by objects, such as the archways that connect the buildings that surround the motor pool of the town.

Fortunately, there is not a lot to do in the mundane world. Even when the player characters need to go to the mundane world, the most that the player would do is get the party from point A to point B and watch some cutscenes. Barely any of the other gameplay mechanisms are functional in the mundane world anyway.

THE MAGICAL WORLD:

The magical world is where most of the gameplay occurs. In this world, the player has more control over the camera.

The gameplay in this world occurs in two modes: overworld mode, and dungeon mode. The overworld mode is where the player characters traipse about from region to region, their travels being abstracted to the appearance of their oversized models moving through undersized landscapes. Dungeon mode occurs when the player characters are exploring dangerous places, e.g. locales that have a lot of “beasties”, as Drippy would say.

The player would be using magic a lot. The magic comes in the form of spells that any follower of the fantasy genre would find familiar. The player would be overcoming obstacles by casting the right spell in the right circumstance. Usually, the results are only described through the statements of NPCs, rather than animated and shown to the player (if Level 5 could not just resort to the use of particle effects).

Most of the combat in the gameplay happens in the magical world too. However, there are a few fights that occur in the mundane world, usually after a character in the mundane world is revealed to have been badly compromised by beings who can apparently influence both worlds.

THE WIZARD’S COMPANION:

The Wizard’s Companion is a book that is revealed and gifted to Oliver early on in the game. It is not a complete book, because many pages are torn out. However, conveniently, the most important ones have been preserved. As the playthrough progresses, characters who want to help Oliver would give him pages to fill out the book with.

The user interface of the book has bookmarks for subchapters and categories, but there are no other aid features such as search queries. Furthermore, the icons and logos that are used in the book are different from those that are used in actual gameplay. The actual gameplay effects of the things that are described in the book are also not mentioned.

The book has its own visual assets, which are different from those that are used for actual gameplay. Thus, players who have difficulty making visual and topical associations might find the Wizard’s Companion to be difficult to peruse. For players who are used to documentation like those in RPG sourcebooks, the Wizard’s Companion would not be much of a problem.

That said, players who are followers of Ghibli’s works might notice Hayao Miyazaki’s hand in the Wizard’s Companion, especially in its illustrations and lore descriptions. These hark back to his days with the Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind manga. This might please players who happen to be ardent fans of Miyazaki’s works.

TELLING STONE:

Fortunately, Level 5 has noticed the aforementioned issue of disparities between the presentation of the Wizard’s Companion and the actual presentation that is used in the gameplay. To address this issue, the Telling Stone is introduced as a character that acts as an on-call tutor.

If the player has any doubt about a certain gameplay element, the player can bring up the Telling Stone’s list of topics. Thankfully, the topics are given concise titles. Selecting a topic has the Stone describing the topic in several statements that are usually just as concise, though the Stone does include some puns or remarks of its own occasionally.

The player should not expect in-depth descriptions of the gameplay elements, however. Things like which ingredients are usually used in which alchemical recipes are not mentioned, for example.

As additional gameplay elements are introduced, the Stone’s list of topics grows longer. Topics that have been added are marked with “new” tags, which help the player know which topics that he/she has yet to read.

GRADUAL INCLUSION OF GAMEPLAY ELEMENTS & CONTROLS:

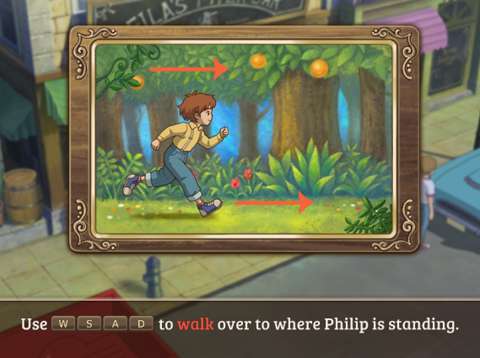

Not everything is available to the player from the get-go. In fact, the control input to make game-saves is not available until after the player has completed Oliver’s first task in the mundane world. Indeed, it can be several hours before the player is introduced to all of the gameplay features in this game.

Although this can give the impression that the game is slow to reveal its best elements, it does have a gradual curve that would not overwhelm the player.

MAGIC – IN GENERAL:

Magic-users are far and few in between; Oliver so happens to be one of them, and his capacity for magic is considerable. However, he is not entirely certain of what he can do and should do. Fortunately, Drippy is experienced enough with magic-users to know what they can do, and he happens to have a copy of the Wizard’s Companion to give to Oliver.

Speaking of which, only spells that are in the book are available for Oliver to use. He is not clever enough to experiment with the fundamentals of spell-casting, much less come up with his own spells. This limitation serves as a light Metrovania element, limiting the places and things that Oliver can reach until he gets the right spell to do so.

However, the progression of the playthrough is such that he eventually gets the spell that lets him overcome hurdles that so happen to be in the way at the time. Therefore, any impression of Metrovania-like gameplay would dissipate quickly.

The original version of the game has the player drawing lines to have the spells cast, but the other versions of the game wisely omits this tedium (among other things).

Suffice to say for now, magic is significant in the gameplay and narrative, but not always in a convincingly satisfactory manner. Level 5’s adaptations also left behind vestiges that had not been cleaned up. These other designs about magic will be described in later sections.

MAGIC POINTS:

Most spells require Magic Points, otherwise known as “MPs”. These are very much the player’s most important resource, more so than even hit points. This is because there are not many ways to replenish MPs, especially when the team is traipsing through dungeons. Unlike typical magic-users in video games, the player characters in this game do not replenish MPs over time.

MPs can be replenished through level-ups, visits to Waystones (these will be described later) and consumption of MP-replenishing items (most of which are magic coffee, amusingly).

This means that romps through the overworld and dungeons can end disastrously, if the player could manage MP consumption carefully. For example, entering a boss fight with diminished MPs is usually a bad idea (especially considering that boss fights are usually preceded by the presence of a Waystone just before their arenas).

SOME SPELLS WITH FEW USES:

There would be many spells that Oliver can use. However, not all of them are usable in actual gameplay. Indeed, there are more than a few spells that seem to be there just for specific moments in the story. For example, the Insight spell is only used once throughout the story of the game, and never once in actual gameplay.

The tell-tale trait of these one-off spells is that they tend to have zero MP costs. The zero cost is there so that the player can use them at the aforementioned story-centric moments, just in case the player has forgotten to refill Oliver’s MP reserves.

Incidentally, some of these one-off spells are vestiges of Level 5’s adaptation of the original Nintendo DS version of the game for other platforms.

INTERACTION SPELLS:

When Oliver and friends are in the overworld, dungeons or towns and cities, most of the spells that the player would be using are spells that are to be cast on NPCs or objects for generally non-violent outcomes. Usually, the player would be using these to overcome obstacles or complete some errands on the side.

GIVE AND TAKE HEART:

The most commonly used interaction spells are Give Heart and Take Heart. There is a narrative element about virtuous elements of the heart, which magicians can skim off and grant unto others. Indeed, there are many errands about finding people who have abundance of one virtue, harvesting some of the virtue from them and finding people to give the harvest to.

Other than the tangible rewards, the only significant value of the taking and giving of virtues is the writing. The player should not expect specially animated cutscenes or even voice-overs.

Indeed, many hours into the game, the narrative element about taking and giving pieces of the heart can seem tiresome to a jaded player. This could have been allayed if story-mandatory segments that involve this narrative element had been presented in ways that are more interesting than just dialogue boxes and eyes of alarming colour. Unfortunately, this is not the case.

COMBAT SPELLS:

Spells that are actually used in fights are fewer in number than interaction spells. Indeed, certain tactical options are only available through the abilities of the player characters’ familiars (more on these later). Even though these spells can harm enemies, the player is better off using the abilities of the familiars instead, especially in the earlier parts of the game.

For example, a familiar with affinity to Wind energies would inflict more damage with a wind/ice spell than Oliver could with the Frostbite spell, if both characters are of comparable levels.

It is only near the finale of the playthrough that Oliver gains powerful spells like Mornstar and Evenstar, which outstrip the damage output of familiars.

Some combat spells do have dual-use as interaction spells. For example, there are frigid places with ice walls that are in Oliver’s way. The Fireball spell happens to melt these obstacles readily.

OVERWORLD – IN GENERAL:

After Oliver has journeyed to the magical world, the player is shown the representation of the lands that he and his friends would journey through. This representation is henceforth referred to as the “overworld”.

The overworld shows the locales that Oliver can go to, as well as the creatures that represent groups of roving beasties. The camera is up above all of these, so the player can see what is approaching Oliver and vice versa.

In the case of locales, coming into contact with the locales usually has Oliver entering that locale. This causes a transition to the other game mode, which will be described later. In the case of groups of beasties, this commences a battle. The facing of the monster group relative to Oliver’s own is a factor, which will be described later.

The player can see the models of other characters that are accompanying Oliver, such as the model for Drippy. These models do not trace Oliver’s steps; rather, they are using their own pathfinding scripts, which also means that they sometimes get left behind when they are caught on collision hitboxes in the overworld.

Fortunately, this is not much of an issue. This is because the representations of Oliver’s companions are only there for aesthetic and narrative purposes; they do not matter in the gameplay of the overworld.

If there are objects that can be interacted with on the overworld, a speech bubble appears over Oliver’s model. If the speech bubble contains an exclamation symbol, entering the control input for interaction has Oliver retrieving something from the object. This is the case for foraging activities.

If the speech bubble has a question mark, Drippy or somebody else in the team would make a remark about what can be done, if it is within Oliver’s power to do so. (There is a recurrent gag throughout the game that despite Oliver’s obvious talent at magic, he is still a slow-learner.)

In the overworld, the player can bring up the game menu at any time to make a game-save. Reloading this game-save returns the player to where Oliver were at the time of the game-save. Some of the state of the overworld is retained too, such as whether foraging points have been foraged or not.

Nearby monster groups are also retained when a game-save is reloaded. However, monster groups that are further away are not retained and are re-populated.

METHODS OF TRAVELLING ON THE OVERWORLD:

Initially, Oliver and company can only move about on foot across the overworld. This quickly becomes an inefficient way of moving about; even an upgrade to Oliver’s movement speed on the overworld does not do much.

Later, Oliver and friends gain exclusive access to a sea-borne ship. This allows the party to reach other islands, as well as return to earlier regions by sailing to their shores, if they have any. This is still not an efficient way to travel, especially considering that the ship has significant inertia that makes it vulnerable to being chased by seaborne monster groups.

Afterwards, Oliver gains the “Travel” spell. This is the premier way to get about; its casting cost is very low and there are no pre-conditions for its use on the overworld. Furthermore, it can be used while the team is within cities and towns. The only limitation is that there are fixed locations on the overworld where Oliver and friends can reappear at, and they can only ever reappear on the overworld and never within locales.

Finally, there is the flying ride. This allows the player to fly to just about anywhere on the overworld, except places that can only be opened up through the progression of the main story. Usually, the visual indication for places that the player cannot go to are clear, such as thick mists that disable the mini-map and prevent any landing.

Speaking of landing, Oliver’s party can only be placed on smooth ground. Any invalid places are indicated with “no entry” symbols, which are usually the case for places like mountains and the seas. However, there are patches of smooth ground that the party cannot land on; these are actually places that are only opened up in the post-game (more on this later). The game does not inform the player about these, however.

CITY/TOWN MODE:

Upon entering a city, town or village, the game switches from the overworld mode to the “exploration” mode. The camera follows Oliver from behind. This gives a restricted view of things around him, but for the purpose of exploring the towns, cities and villages, this is good enough, mainly because there are no threats to Oliver and pals in these places.

What the camera shows is not enough, however. The player will need to bring up the map for these places, or observe the mini-map, if only to identify which NPCs are relevant to “errands” and other jobs that Oliver can carry out.

DUNGEONS:

Some locales in the magical world are practically video game dungeons, even if they seem to be outdoors. Amusingly, the game refers to these places as “Dangerous Places”.

When Oliver and company go to these places, the game switches to a camera view that is like the one that is used when they are in cities or towns. The camera view is generally inadequate for knowing where threats are.

Speaking of which, these places have monster groups appearing and wandering about just like those on the overworld. These generally spawn far away from where Oliver and company are. Therefore, if the player has cleared a small area of monster groups, there will not be any that can threaten the player in the immediate area. Of course, existing monster groups can still wander into the vicinity of the player character.

The monster groups do not appear on the mini-map, for better or worse. Considering the limited camera view, this will not be helpful for noticing any monster groups that may be coming up on the player character from behind. Thus, the player has to rely on other means to notice these occurrences, such as the sound clip that plays whenever a monster group has spotted the player character.

When entering a dungeon for the first time, the mini-map is almost completely obscured. More of it is uncovered as the player character traipses through the dungeon. However, the exact spots that trigger reveals of portions of the mini-map are not shown to the player, so the player would need to have Oliver wander about before being able to reveal more of the mini-map.

The mini-map is at least useful for knowing where the level boundaries are. Any borders with solid lines indicate the presence of these boundaries; having Oliver run up to them merely has him running into invisible walls if there are not any opaque walls to be seen.

The presence of faded-out paths and the absence of solid lines indicates transition to a different section of the level, usually vertically above or below the one that the player character is currently on. Alternatively, if the faded-out paths on the mini-map seems to lead into what should have been a solid wall, the player may be looking at illusory walls that lead into hidden routes.

At the same time when Oliver gains the “Travel” spell, he also gains the “Vacate” spell. This spell lets the team exit from a dungeon, placing them just outside the locale. This is useful, especially considering that monster groups always repopulate where the team has gone through and that Waystones and Familiar Retreats are always close to the entrance of a dungeon (more on these shortly).

NO GAME-SAVES IN DUNGEONS AND COSTLY REVIVES:

Game-saves cannot be made while traipsing through dungeons. This is important to keep in mind; a lot of progress can be lost if the player suffers a team-wipe (or a game crash, though these never happened during my time with the game).

Speaking of wipes, the game will pose the player with two choices if the team is defeated. Firstly, the player can revert to the most-recent game-save, which means a definite loss of progress. Second, the player gives up a portion of the team’s accumulated gold to be revived at the entrance of the dungeon, but otherwise retains any permanent progress through the dungeon, any experience points that have been accrued and any loot that has been acquired.

WAYSTONES:

Waystones are relics that are located around the magical world. They are only useful for people that have an affinity to magic, namely the player characters. Interacting with any Waystone immediately restores them to hale health and vigour, while removing any ailments.

Conveniently, these are located at the entrances of any dungeon, and often just before encounters with particularly powerful enemies. Waystones are also the only means of making game-saves in dungeons.

CHESTS:

For whatever reason that is not clearly explained in the narrative of the game, there are chests that can be found throughout the magical world. Some of them are deliberately used to store things, but others seem to be there just for Oliver to loot. NPCs generally do not acknowledge their presence.

There are several colours of chests, though all of them use the same model. This can be a problem for colour-blind players, especially considering that the chests’ colours are not of considerable luminance.

That said, the most common chests are the red ones, which can be readily opened. Consequently, they usually have the least valuable loot, excepting the chests that are not easy to spot and find.

Next, there are blue chests. These are magically locked, and have to be opened with the “Spring Lock” spell. The spell does cost a bit of MPs, so this can be a minor concern when traipsing through dungeons.

Then, there are green chests; these are the most finicky. These are generally out of direct reach of the party; thus Swaine, who is one of the human party members, is required to get them. Yet, the perennial problem with them is that the player only gets the prompt to use Swaine after the player has positioned Oliver at the right spots. These spots are hidden to the player.

(The only rule of thumb about these spots is that when the player character is on them and looking at the chests, the player would be looking at the front side of the chests.)

Finally, there are purple chests. These have to be opened with the Spring Lock spell too, but only after Oliver has obtained a certain legendary wand.

Overall, getting loot from the chests would be a droll activity for jaded players. Some of their loot are gear pieces that cannot be obtained elsewhere, but the player might already have the most top-notch gear for the team prior to opening the chests. Indeed, a meticulous player might find that the rewards from chests are merely decent at best, and are generally lousier than the rewards from pursuing errands.

MONSTER GROUPS:

Perhaps wisely, Ni No Kuni utilizes the present-day Japanese role-playing game (JRPG) convention of showing monster groups on-screen, rather than the random combat encounters of older JRPGs. That said, as mentioned earlier, monster groups appear as models of individual beasties on the overworld and in dungeons.

The aforementioned models of individual beasties indicate guarantees of the inclusion of that type of creatures in the monster groups. However, the models do not indicate their actual numbers and certainly not actual compositions of the groups.

The models that are used for monster groups do happen to influence their movement speed; this is the only reliable certainty that the player gets from their appearances. Typically, having models of creatures that happen to have fast movement speed in actual battle would result in a monster group having considerable speed on the overworld and in the dungeons, and vice versa.

For example, some monster groups in the Autumnia continent have the model of the Tin-Man creature, which is slow. Consequently, these monster groups are laughably slow.

In the case of monster groups at sea, all of them use the same model: a creature that is underwater and whose features have been reduced to an amorphous blob, save for two white eyes. Consequently, encounters with these monster groups are more uncertain.

Most monster groups follow the default scripting, which will be described shortly. However, the actual composition of a monster group also determines its response when it detects the player characters. For example, monster groups that have the Danglerfish and its advanced forms are always hostile to the player characters and will give pursuit.

LEVEL DIFFERENCES:

The aforementioned default scripting for the response of a monster group to the presence of the player characters is determined by the difference between the average levels of the members in the monster groups and the average levels of the player characters.

If the player characters are of an average level far beyond that of the monster group, the monster group would run away from the player characters.

If the player characters are of an average level that is in the vicinity or under the average level of the monster group, the monster group would likely give pursuit. Having greater average level reduces the likelihood of them giving pursuit, in which case the monster group runs away instead.

SIGHT ARCS OF MONSTER GROUPS:

Interestingly, all creatures in the magical world has eyes that face forward; this applies to even the most bizarre of them. Consequently, monster groups are not aware of anything that is behind them. Most of them have frontal arcs that are initially 150 degrees; there are upgrades for the player characters that narrow this arc.

The sight arcs of the monster groups would be of importance in sneaking up to them; this will be described shortly.

COMBAT ENCOUNTER:

A fight occurs after the player character comes into contact with a monster group, regardless of their relative facings and what they are doing. However, their relative facings do determine how the combat starts.

If the front facing of Oliver’s model comes into contact with the rear arc of the monster group, the player characters gain an advantage over the monster group. The monster group cannot make any attacks and significant actions for several seconds, other than turning around to face the player characters.

If the monster group comes into contact with the rear arc of Oliver’s model instead, the monster group gains the advantage. The player characters are not allowed to take any significant actions, and the player is forced to start with Oliver and cannot switch characters until several seconds later. However, the player characters can still move around; the player will want to move the currently controlled player character around to avoid getting mobbed. (The actual mechanisms will be described later.)

A LOT OF COMBAT ENCOUNTERS:

It would not take long for an observant player to notice there is a preponderance of combat encounters in this game. Indeed, due to the aforementioned issue of constantly respawning enemy groups in both the overworld and in the dungeons, a significant portion of total time that is spent in this game is spent on fighting monster groups.

Furthermore, in turn, a substantial portion of this time is spent watching the ending animations and statistics screens of concluded fights. These cannot be skipped.

Fortunately, the developers have noticed this issue, and implemented the solution that is the aforementioned response of monster groups to the average level of the player characters. Yet, this solution only partially addresses the problem, due to the aforementioned behavior of monster groups that have creatures that are inherently hostile.

PROBLEMS WITH ENEMY GROUPS RUNNING AWAY:

Unfortunately, there are some hiccups in the programming of overmatched enemy groups running away. These groups are supposed to run in a direction away from the player character, but some run towards the location of the player character when the running-away script was triggered. The player can dodge these groups in order to avoid them; they run past the player character. However, it would be apparent that there is some coding error.

In dungeons, the trouble from this problem is compounded further by the limited space in the dungeon environs.

This behavior scripting also goes against the errands that are about capturing specific creatures. If these creatures happen to be fast ones and they represent their groups on the overworld, they might be able to run away before the player character catches up to them. The player can compensate by using stealthy tactics to ambush them, but this is still busywork.

THE HUMAN PLAYER CHARACTERS:

The player can have up to three human player characters in the team. They are the player’s main assets. Each has different capabilities and gear.

The player begins with Oliver, who is the only wizard in the team. Incidentally, among the three, he has the greatest MP pool. Furthermore, due to the spells in his book, Oliver has the greatest variety of actions that he can perform in fights. However, Oliver is the least capable player character at physical fighting; hitting things with wands is not going to do much. Yet, being the main player character, Oliver is always in the party.

The player gains Esther next. Esther has the ability to use magical musical instruments. She has few abilities initially, but eventually she gains more. She becomes the main source of buffs for the party, more so than Oliver is. Esther is also the only character that can recruit beaten creatures into the team, thanks to some silly narrative element about potential familiars liking magical music a lot after they have been beaten up.

Swaine is the third and last human player character. His specialty is the use of a versatile handgun. His handgun can fire wires that can somehow pick open green chests from afar and retrieve their contents; he cannot do this for other chests, for whatever reason. Anyway, during combat, he can fire shots that inflict de-buffs on enemies, though bullets generally do little damage in the magical world.

(The wires that are purportedly coming out of his gun are never shown anyway.)

Marcissin is the fourth and final player character. He does not have any unique special abilities, but he is a wizard, meaning that he can be an additional spellcaster in case Oliver is not enough. However, he has his own set of spells, and cannot cast certain spells in Oliver’s book. Nonetheless, he is more adept at spellcasting; this is expressed as noticeably shorter wind-up time for his spellcasting animations.

After he is introduced, the player has to decide which two of the three characters after Oliver to include in the party. Esther is likely a default inclusion, mainly because of her ability to recruit familiars, but there are fights where there are no recruitment opportunities.

The humans can only wield weapons that are specific to their professions. Only Oliver and Marcissin can exchange their spellcasting implements, which is shown on their models. (The implements are conveniently objects with rod-shaped handles, so animating their wielding is not much of a problem.) Other than these, any of the humans can have two accessory-type items, and that’s it.

The human player characters are generally always in the team, though Swaine does briefly leave the party for a short while due to a narrative reason at one point in the playthrough.

Since they are almost always in the team, the humans would have levels that are higher than those of their familiars. This is just as well, because the familiars use certain statistics that are derived from their human compatriots’. This will be elaborated later.

FAMILIARS – OVERVIEW:

Many of the non-sapient creatures in the magical world are borne from the hearts of living sapient beings, which include humans and other anthropomorphic species. These non-sapient creatures are generally spoiling for a fight, so they represent constant threats to the peoples of the magical worlds.

Fortunately, the same creatures can also be befriended, if they are not already bound to the persons who created them from their hearts in the first place. Creatures that are defeated in combat may come back up, fawning at those who defeated them. With the correct serenades, these creatures become familiars.

This is really Ni No Kuni’s take on the concept that Pokemon established.

The human player characters are generally too squishy for prolonged fights and they have anemic damage output with their default attacks throughout the entire game. Thus, familiars are the player’s main means of taking hits and dishing them out.

Each human player character can have up to three familiars that are bonded to their hearts at any time. During combat, only one of these three familiars can be directed around by any human character. Any damage that their human lieges would suffer are suffered by them, and vice versa.

That said, since a familiar is drawn out of its handler’s heart, its HPs and MPs are based on those of its handler. Thus, a high-level familiar would have the same MPs and HPs as a low-level familiar, if they have the same handler. However, this does not mean that they are interchangeable; indeed, such a logical leap can be disastrous.

Rather, each familiar has its own set of statistics other than HPs and MPs. In turn, these statistics are determined by their levels and combat archetype.

COMBAT ARCHETYPES OF FAMILIARS:

Officially, familiars are categorized into genus, elemental affinity, astral signs and such other lore-related terms. Meticulous players would rather categorize them according to their actual worth in combat.

Some familiars are made for hand-to-hand fighting; these include the Mite that Oliver gets early on in the game. These familiars can take hits and dish out their own quite reliably, so it would be understandable that most players would have these as core members of the team.

Some familiars are push-overs in toe-to-toe fights. However, these can learn buffs and de-buffs that can tip the scales. Many of these physical push-overs also happen to have high magical attack ratings, thus making them suitable for making magical attacks of specific elements against enemies that are vulnerable to them.

MOVEMENT AND ATTACK RATES:

The familiars can also differ greatly in their rates of attacks and movement. For example, the Mite scampers about quite quickly and has a decently fast attack rate. However, there are familiars that are faster on the move, such as the lemur-like beast familiar that is introduced next. In contrast, some familiars are really slow on the move, like the Tin-Man series.

Keeping this in mind is important, because everyone constantly moves about in combat. There are attacks that can hurl their targets far away, so slow movers will have a problem in maintaining their onslaught.

FAMILIAR SIZES:

The sizes of the familiars are also a significant factor in combat. Familiars like the Mite are small, which reduces their hitbox sizes but also diminish their reach. In contrast, large creatures like the Tin-Man series are huge.

There are no familiars that can use ranged attacks by default, so reach in melee combat is a concern throughout the game. Of course, unique enemies, such as the bosses defy most of the limitations that affect familiars.

CERTAIN OVERPOWERED FAMILIAR:

For better or worse, there is a familiar that does not have significant limitations that balance against its advantages.

Most of the familiars that were in the base game package for the DS version of the game are balanced. These include the familiars that can be beaten and recruited into the party. These also include most of the familiars that can only be obtained by redeeming tickets through the Supreme Sage, who is a certain character that represents a major milestone in a playthrough.

There is one of these tickets-only familiars that is incredibly powerful. This is the Griffy series, which are this game’s take on the mythical griffon. It is a creature with high statistics in just about everything. It is likely to be more powerful than other familiars that had been in the active roster as long as it had.

Such a familiar can render otherwise tough fights very manageable even for incompetent players, in that at least one active member in the team is still up and about to do something.

Fortunately, in the long-term, the potency of this familiar eventually peters off, mainly due to the low limit on its character level.

FEEDING FAMILIARS:

Familiars are technically ageless beings (even though some of them visually ages as they turn into advanced forms) and they do not really need to eat. However, they can still consume things and derive benefits from what they eat.

The benefits from any type of food are shown to the player. The magnitude of the benefits are also shown, so the player can gauge how much progress has been or would be achieved from feeding the familiars.

The benefits are measured in terms of points. These points go into meters that are associated with the statistics of the familiar. When a meter is completely filled, the familiar gains one point in the statistic that is associated with the meter; any overflow goes into the progress of achieving the next point. The threshold for the meter then increases, meaning that each subsequent increment for that statistic requires more of the associated food to be fed to the familiar.

It might be tempting to work around the issue of diminishing returns by feeding different foods to a familiar so that it gains the most out of every feeding binge. However, there is a limit to this, which will be described shortly.

FAMILIAR’S FAMILIARITY:

Peculiarly, familiars have preferences towards specific kinds of foods. These preferences are usually determined by their genuses. For example, Milites familiars (that is, familiars that are pre-disposed towards fighting in melee combat) have a preference for chocolates.

This is important to keep in mind, because it is associated with the limitation that is imposed on the amount of statistical increments that can be gained from feeding familiars.

The player is shown the “growth limit” of a familiar when in the “Familiar Cage” screen, which is the user interface for feeding things to the familiars. Each statistical increment from feeding contributes to the counter that is bounded by the growth limit. Reaching the growth limit means no further statistical increments are possible.

However, the growth limit can be raised by increasing the familiar’s familiarity with the player. This can be done simply by feeding the familiar with its preferred food. A meter that is represented with hearts is next to the aforementioned counter; the hearts fill up as the player feeds the familiar with its preferred foods. Each filled heart extends the growth limit by 10 points.

FEEDING IS ULTIMATELY INCONSEQUENTIAL IN THE LONG RUN:

Unfortunately, the statistical increments from feeding are small, compared to the amounts of increments from gaining levels. Even the familiars with the slowest growth rates in its statistics have increments from levels that are more significant than those that it could gain from eating.

Ultimately, feeding is only useful when the familiars are at low levels, or after they have reached their maximum levels.

FAMILIAR EQUIPMENT:

The various shapes and sizes of familiars render the prospect of physically equipping them with things to be an impossibility. After all, some of them do not even have limbs, or are just too small and dainty to have anything on their person.

However, their ability to eat things and derive benefits from them happens to overcome this issue. Somehow, familiars can encase pieces of equipment in bubbles, shrink the bubbles and their contents, and then ingest the bubbles. This is not shown through in-game animations, but through artwork that has been made for the Telling Stone’s lessons and the Wizard’s Companion.

That said, the benefits from each gear piece are shown to the player in the inventory management screens. The gear pieces can be removed and given to others; according to the narrative, the familiars simply regurgitate the bubbles with the gear pieces.

There is only one significant limitation to kitting out familiars with gear. Each distinct series of familiars can only have a specific combination of three pieces of gear. For example, the Mite series can have a sword, a shield and a badge; they cannot have anything else. Some other series cannot even have weapons of any kind, such as the plant-trap series.

Consequently, the player needs to have a variety of gear pieces, including spares, in order to kit out the familiars that would be fielded in battle.

FAMILIAR TRICKS:

With the exception of Oliver, the human party members gradually and continuously learn new skills as they gain levels. These skills – and Oliver’s spells – can be accessed quite readily; Oliver’s spells in particular are selected through a vertical list that appears on-screen.

Familiars develop new abilities as they grow in power too; these abilities are known as “tricks” in the parlance of the game. The player is shown the levels at which they learn tricks, which is convenient.

That this is shown is just as well, because familiars can only learn to use a limited number of tricks in battle. This number is represented by the number of trick “slots” that they have. Their character level determines how many slots that they can have; generally, higher-level familiars have more slots.

There is also the maximum number of tricks that the familiar can learn. If the familiar learns a new trick but has already reached its maximum number, the player is prompted to pick one of the existing tricks for the familiar to deliberately forget and replace with the new trick. Alternatively, the player could skip the process, if the player deems the new trick to be undesirable for that familiar.

TRICK GEMS:

Familiars can also somehow learn tricks by eating Trick Gems. These will count towards their limits of Tricks, so the player will want to carefully consider the use of these items.

Still, there are some generally wise decisions. For example, tricks that bolster a familiar’s main function in battle would be useful, e.g. give gems with area-effect Tricks to familiars that have high Magic Attack ratings.

SIGNS:

The genus and species series of the familiars generally do not matter much in combat. However, their “signs” do. “Signs” are the game’s additional take on elemental strengths and vulnerabilities that are so common in games with fantastical combats. In their case, their mechanism is that of rock-paper-scissors.

There are four types of signs, each with two variants in turn. These are the Sun, Moon and Star, and the Planet. The Planet is mentioned separately from the rest because it is the only one that does not partake in the rock-paper-scissors relationship. Speaking of which, the Star, Moon and Sun are the equivalent of rock, paper and scissors, respectively.

Any advantage of one over another manifests in the form of additional damage against the disadvantaged, and reduced damage taken by the advantaged. This is a considerable difference, so it is in the player’s interest to field familiars with different signs so that they can be matched appropriately against their opponents.

The Sun, Moon and Star signs have variants that are visually represented as double the number of celestial bodies. In their case, the effects of the aforementioned advantages and disadvantages are magnified, especially if these variants are pitted against each other.

ELEMENTAL AFFINITIES:

In addition to signs, Ni No Kuni also has the traditional elemental affinities. However, these do more than just rock-paper-scissors mechanics.

There are six elemental affinities, and each in turn is represented as a variable with three statuses in descending order (according to their coding): attuned, neutral and averse.

Familiars that are attuned to an element can be fed trick gems of types that are associated with the element; these gems are otherwise inedible to other familiars. These familiars also get bonus output from using tricks that are associated with the element. Finally, they are very resistant to any incoming damage that is associated with that element.

Familiars that are neutral to an element have moderate responses to any incoming damage of that element, and of course, they cannot eat trick gems of that element.

Familiars that are averse to an element certainly cannot consume any trick gem of that type of element. They take more damage from attacks that are based on that element too. If they can somehow use abilities that are associated with that element, their attempts are diminished, at best.

AFFINITY-ALTERING GEAR PIECES:

There are some gear pieces that are supposed to increase or change “resistance” to certain elements. However, the coding of the gear pieces alters the affinity of the familiar, usually by a step increment or decrement according to the aforementioned order of statuses.

This means that a familiar that is neutral to an element may become averse or attuned to it. In the latter case, they can consume trick gems that they usually cannot.

METAMORPHOSIS:

The familiars can change into advanced forms of their species line after they have gained enough levels. This is called “metamorphosis” in-game.

It is unclear when this can happen, however; there are no visible trackers for measuring progress towards this. There is no clear pattern to be discerned from creatures of the exact same species either.

Anyway, after a familiar advances into its more potent form, it gains better statistical increments from level-ups and potential to learn other kinds of tricks. Any tricks that it has learned is retained, as is any statistical increment from eating things.

However, its statistics are diminished across the board, and its level is reset to 1. There is no clear pattern to how much is lost.

Fortunately, since the familiar has its level reset to 1, it can gain levels at faster rates than before. On the other hand, advanced familiar forms have higher XP thresholds, meaning that they do not gain levels as fast as they had when they were in their previous forms.

Metamorphosis can also change the celestial sign of a familiar, which may or may not be to its detriment. For example, the Mite series starts with the potential to learn Fire-based tricks. However, if the earlier forms metamorphoses into the Mermite – which is one of its two last forms – they gain an aversion to fire. This would require re-customizing of its learned tricks.

CANDY DROPS:

The main hurdle to metamorphoses is that they can only happen after a familiar has been fed special candy drops. These begin to appear after the player’s familiars have reached levels at which they can metamorphose.

The drops are meant to let the player decide whether to continue pursuing levels for the current form of the familiar, or to advance their forms. The former decision might not be worthwhile in the long run, due to limitations on the levels of the familiars, but that decision would not require the player to keep the candy drops in reserve.

The latter decision would have to be deferred if the player does not have the necessary candy drops. The regular kinds drop readily enough, but the Jumbo variants, which are needed for the final metamorphoses, are rare drops that can only be had from end-game enemies. The materials to make the Jumbo variants through alchemy (more on this later) are similarly not easy drops.

Speaking of alchemy, the regular variants cannot be made through alchemy. They cannot be bought either.

There is another source of Jumbo drops, but this one requires the player to gamble on his/her luck; this will be described later.

Thus, the player may have to stow away familiars that are ready to metamorphose, just so that they do not get XP that could have gone to other familiars.

ALCHEMY:

Almost one-third into the first playthrough, the player is introduced to the feature of alchemy (after a hilarious boss fight of sorts). Oliver does not have chemistry or cooking skills, but the alchemy pot and its resident genie more than compensate for this.

That said, all the player needs to do is hand the materials and ingredients over to the genie, who then attempts to cobble them together with the magic of the pot. If the player gets the combination of items right (as according to the written code for alchemy in this game), the genie produces something and the materials and ingredients are consumed.

If the player gets the combination wrong, a silly animation plays out, but the materials and ingredients are conveniently and thankfully not consumed. However, the animations do take a while; the player of course cannot recover the time that has been wasted.

CHYMISTRY WITHOUT FORMULAE:

The player can manually select ingredients to hand over to the genie. This is necessary if the player does not have the formula for making something, and instead has to look at other documentation, like the illustrations in the Wizard’s Companion.

However, each product has to be made one by one. It would not take long for most players to become annoyed by this method of using the alchemy feature.

WORKING WITH FORMULAE:

Although wizard alchemy is exclusive to wizards, there are people who are fascinated with it and have collected formulae that could only ever be used with alchemy pots. Incidentally, Oliver starts with no formulae at all, and has to receive these from other people that have them.

The player can actually make things with formulae, as mentioned earlier; this includes any product that is mentioned in the formulae themselves. However, with formulae, the player can choose how many multiples of the product to make; the user interface automatically limits the amount depending on the number of ingredients/materials available.

GETTING INGREDIENTS AND MATERIALS:

Most ingredients for treats can be bought from the Hootique Shops in every major population center, or from merchants that do stock ingredients. However, everything else that is needed for alchemy needs to be found elsewhere.

Materials for pieces of gear, in particular, cannot be bought. There are some errands that do yield these as rewards (more on errands later), but of course these are one-time-only.

There are spots in the overworld that can be foraged for materials. These spots are highlighted with sparkly lights that may be difficult to notice at high camera zooms. Furthermore, what they yield are not easily discernible for the new player, though their yields are usually endemic to the region in which they occur. These spots respawn every dozen minutes or so, so the player cannot forage from them continuously.

(Anal-retentive players can try to come up with a foraging circuit after getting the flight-capable ride. However, waiting for the animations for getting on or off the ride can be irksome.)

Then, there are the prizes at a casino (more on this later). These prizes include high-grade ingredients that generally cannot be found elsewhere. Thus, the player would not be making the highest-grade treats for familiars without these ingredients.

Then, there are the rewards from winning fights with specific species of familiars. The Wizard’s Companion does show what each documented species would yield. However, whether the yields occur or not still depend on the player’s luck.

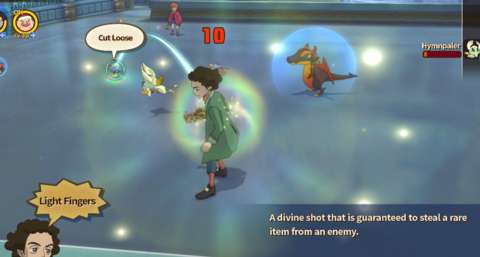

STEALING WITH SWAINE:

Swaine’s skill with his special gun is meant to give the player a more deterministic and repeatable alternative of getting items than depending on lucky yields or time-consuming foraging circuits.

Swaine has some special shots that can be used to steal items from enemy creatures – and only ever enemy creatures. The shots yield nothing when used on special enemies, like the one-of-a-kind bosses.

Unfortunately, the outcome of these shots is still dependent on luck rolls. Swaine may come up with something, or he may come up with nothing. Even if he does come up with something, a creature has a permutation of yields, of which only one would be given to the player. After an item has been nicked off a creature, it can no longer have items stolen from it. The creature is not marked in any way, however.

COMBAT MECHANISMS - OVERVIEW:

Combat is a pseudo-real-time affair. Every combatant has to act according to an assortment of cool-down timers, of which there is one for just about every action. However, while waiting for the cooldown timer for an action to refresh, a combatant can take another action.

Certain actions, such as the casting of spells and the usage of tricks, have wind-up animations that have to be fully performed before the actions are enacted. These animations can be interrupted, usually by hitting the character hard enough. The human player characters are particularly vulnerable to such occurrences, especially spellcasters like Oliver and Marcissin.

While the cooldowns for recently-enacted actions are running down, the player characters can perform other actions. An observant player can have a character perform alternating actions without wasting time that is expended on cooldowns.

There are two camera settings that are used in combat. The default camera setting follows the player character around, while being directed at the center of the arena. Targeting an enemy causes the camera to look at the target.

The other camera setting is used for cinematic angles. This setting occurs whenever a character enacts a particularly potent action, which is shown via an in-game cutscene. Cooldown timers do not cycle during the cutscene.

The abovementioned designs are all easily observable and learned. Unfortunately, the other designs are not so, and these are where the game shows its shortfalls at explaining things to the new player.

ATTACKS – OVERVIEW:

Attacks can be typified according to how they are coded. Unfortunately, how exactly they are coded and how the coding is carried out is not told to the player.

Observant players who are experienced in video games and have learned things about how combat is typically coded can recognize the workings almost as soon as they happen. To anyone else though, learning about the differences between the types of attacks can be unpleasant, because these differences are often exhibited by enemies instead of the player characters.

DEFAULT ATTACKS:

Firstly, there are the default attacks that any character can make. These are always melee attacks, for better or worse; for example, Oliver whacks things with his wand. Even Swaine hits things with his handgun.

That said, default attacks require that the attacker is next to its target and facing it. If this requirement is not fulfilled, the melee attacks are guaranteed to miss; there would be no RNG rolls at all.

If the requirement is met, there will be a roll of the attacker’s Accuracy rating against the defender’s Evasion rating. Thus, even hits that look like they would connect can miss.

Default attacks have almost no wind-up. Even though damage is inflicted at the end of the attack animation, the accuracy roll against evasion has already happened at the beginning of the attack animation. If the target manages to get away during the animation, it would be hit anyway if the roll is successful.

When a character performs default attacks, the attack command is replaced with a cooldown timer. As this timer counts down, the character performs attacks as long as the enemy is within range and if the character is able. During this time, the player cannot move the currently-controlled player character.

FAN ATTACKS:

Some tricks and abilities are implemented as “fan” attacks, to use the game’s own words. Experienced combat RPG players would recognize these as the equivalent of “cone” attacks, to use (similarly poorly-conceived) phrases from Western tabletop RPGs.

Anyway, an arc of particle effects radiates outwards from the attacker; anything that is caught in the arc is hit. There are no rolls against evasion. This advantage for the attacker is much needed, because the target and other characters can still move around and take major actions while the arc radiates outwards.

ATTACKS ON ALL ENEMIES:

Some attacks target all enemies. There are in turn two kinds of these: one that arranges the enemies for a cinematic view of them being hammered, while the other one shows visual effects emanating from the center of the arena to harm any enemy caught in the waves.

In the case of the former, the arrangements are only for the purpose of the cutscene. The game will revert the characters to their previous locations. On the other hand, the abrupt changes can be annoying if the player is meticulous about grouping enemies for fan attacks.

DE-BUFFS:

Attacks that apply de-buffs use the same coding as those for offensive attacks. There is generally no issue with the application of de-buffs, other than the RNG rolls that have to be done because they use the code for attacks.

Most de-buffs are not worthwhile, mainly because their wind-up animations take too long, they last too short or their effects are not that great. (For maximized effects, the player would want to have magic-oriented familiars use de-buffs.)

However, there are some that are useful. For example, Nix is a de-buff that prevents the victim from using spells or abilities; this will be particularly useful against creatures that have troublesome powers, like the ones that heal their entire team.

BUFFS FREEZE THE TARGET:

Buffs generally increase statistics; they are straightforward to use. Healing spells are also implemented with the same code as buffs. Unfortunately, buffs have a problem in their implementation.

The problem is that the application of the buffs and healing require the target to stay still while receiving the benefits. This is very undesirable if the player is trying to have a character move away from enemies that are mobbing him/her/it.

The most that the player could do is to disable CPU-controlled party members from using any abilities, which would prevent them from applying buffs or healing at the wrong times. Yet, this just highlights how unreliable that CPU-controlled party members can be.

UNRELIABLE CPU-CONTROLLED PARTY MEMBERS:

Speaking of which, Ni No Kuni suffers from the same issue that plaques video games with CPU-controlled party members: they are just not reliable.

The player can only control one party member at a time; either one of the human player characters, or his/her familiar. The other two party members are controlled by the CPU. They are just not good at decision-making.

As mentioned earlier, MPs are precious. Unfortunately, CPU-controlled party members spend their MPs left and right with little efficiency, such as applying buffs for a fight with overmatched enemies. Coupled with the mechanism of Glim (which will be described later), the player would find it hard to have the party spend their MPs efficiently without holding the hand of each and every one of them.

FAMILIAR STAMINA:

For whatever reason, familiars cannot stay deployed in combat forever. There is a “stamina” meter that determines the time that they have left before their human handler has to switch to other familiars or back to themselves.

Only a few accessory items affect the stamina meters of familiars. A few rewards from quests also increase the capacity of the meters. However, there are no other gameplay designs that affect stamina. This gives the impression that this gameplay element is just there so that the player does not get to use his/her favoured familiar all the time.

REVERTING TO THE HUMAN CHARACTERS:

When the human party members deploy their familiars, the familiars pop out from the chests of their models; this is expected, because the familiars are borne from their hearts.

After this happens, the familiars become combatants in the place of the humans. The humans then withdraw to the circumferential edge of the arena, cheering on their familiars. For better or worse, this is not just for aesthetics.

While the humans are cheering their familiars, they are rendered invalid targets for the application of damage. To elaborate, area-effect and all-enemies attack can hit them, but no damage is applied. This is odd, but convenient.

However, if the humans have to recall their familiars and take to the field themselves, they revert to the status of combatant, exactly at where they are. If they happen to be too close to enemies at the moment, they are in trouble. There is little that the player can do to control their movement around the edges of the arena. On the other hand, if the player is certain that the humans are far away from enemies, the player can switch control over to the humans and recall any familiars that are in trouble.

GLIM:

Ni No Kuni’s combat has a feature that is rarely seen in video games, likely due to how difficult it is to code and execute properly.

Anyway, this feature involves hitting enemies such that things pop out of them, even while they are still alive. These things are not just for aesthetics, because they have gameplay significance. Typically, the player character must deliberately collect these because they are not automatically collected.

In the case of Ni No Kuni’s take on this feature, these things are called “glim” in-game. These appear as colored orbs that are floating about, waiting to be collected.

There are two overarching types of glim, which are differentiated only with the colours of green and blue. This can be a problem for players that have colour blindness that involves these two hues.

Anyway, the green glim heals the character that collects it, whereas the blue glim replenishes MP. There is no clear pattern as to which glim is produced when enemies are hit, though green glim is noticeably more common.

Glim eventually disappears, so the player will want to keep an eye out for them and collect them wherever possible and/or convenient.

CPU-controlled party members are well aware of the presence of the glim. They will collect them whenever they can, especially if they are in need of MP to use an ability that they have decided on. This also means that the player would be competing with them for glim.

“NICE!”:

Ni No Kuni’s combat also has a feature that rewards the player for timing attack actions.

When enemies intend to perform their default attacks, the beginning moments of their attack animations are when they are vulnerable to being interrupted. If they are hit hard enough during these moments, their attacks are cancelled. They have to wait for their attack actions to finish their cooldowns before they can attack again.

If an enemy is winding-up for an incoming attack, hitting that enemy hard and repeatedly might just cancel the attack before the wind-up finishes. This is not easy to pull off, but it can happen.

These occurrences are accompanied with a disembodied audience shouting “Nice!”. There is a hidden counter that tracks the number of “Nice!” announcements. This counter is carried over from fight to fight.

SUPER GLIM:

The aforementioned counter eventually leads to the appearance of the “Super Glim”. This is a bigger than usual glim that is bright and yellow. The player will want to get it as soon as possible, because its presence on the field is even shorter than those of regular glim. For better or worse, even the CPU-controlled party members will go after it.

Retrieving the Super Glim completely heals the party member that collected it, while super-charging it for a special action. The party member’s next action is locked to that special action, for better or worse.

Each human character and line of familiar species has its own special action. For example, Oliver’s special action is Burning Heart, a much bigger fireball that he hurls at the target. Typically, super-charged attacks inflict considerable damage. Alternatively, the special action may be a powerful buff, such as Inner Strength, which doubles damage per hit and doubles attack rate too.

BOSSES:

Bosses are particularly powerful enemies. There is usually ever only one enemy in every boss fight. (The final boss is assisted by rather powerful minions of its own, thus making that boss fight more troublesome than most.)

Bosses are immune to all de-buffs. Despite their size, bosses that are mobile can move with incredible speed around the arena. Indeed, familiars would not be so useful in these fights, mainly because they have to chase the boss around to hit it with their default attacks.

Bosses have powerful attacks, as to be expected. The player will want to observe the animations and the text bubbles that appear over them, if only to know what they intend to do.

Still, experienced players would not find them too difficult. At worst, these fights are battles of attrition that can be won by having enough supplies and being mindful of when to consume them.

“CHANCE!”:

The greatest reason that the boss fights should be manageable for anyone that is not wretchedly incompetent is that the bosses have rather embarrassing vulnerabilities.

After a minute into each boss fight, or after the boss has done something nasty, Drippy would jump in and inform the player about the boss’s vulnerabilities or tells. Usually, the player can do something to exploit these. The easiest example is hitting the boss with the right spell.

When the boss’s vulnerability is exploited, the boss is staggered and rendered helpless for a while. The boss does not take any more damage in this state, but there is nothing that it can do about the player piling as many attacks on it as possible.

MINI-BOSSES:

There are some particularly large familiar-like creatures that the player can never recruit. Incidentally, these creatures are the targets of bounty quests. They are often found in specific regions of the world, because they are menaces that are endemic to these places.

Like regular bosses, these are immune to all de-buffs. However, they have no particular weakness that can be exploited to render them helpless. They are also often accompanied by other creatures. On the other hand, they are not as daunting as the bosses.

DEFENDING:

In lieu of going on the offensive, the player can have a player character adopting a defensive stance. This is unique only to the player characters, and is the player’s main means of pulling through tough fights.

Any incoming attacks that land on a defending player character inflict very little damage. This also counts as a “Nice!” occurrence.

To prevent the player from exploiting this feature so readily, defending has a cooldown timer, like any other major action. The character will have the defensive stance during the first half of the timer, but the second half has the character dropping that stance. This means that the player must time defenses carefully, lest the player character is hit with an attack during the latter half of the timer.

Timing defenses is not always easy though. Some enemies have powerful attacks with short wind-ups, or they begin their wind-ups while the player character is doing his/her/its own wind-up.

TEAM ALL-OUT ATTACK AND DEFENCE:

There is initially nothing that the player can do to actively direct the CPU-controlled party members. The most that the player has is the “Tactics” command, which can only be used during battle to set their behaviours.

After an encounter with a certain powerful enemy, the “All-Out Attack” and “All-Out Defense” commands are made available. The former causes the CPU-controlled party members to focus on attacking the enemy. However, this might also cause them to switch their familiars, which may or may not be desirable.

The latter command is much more needed than the former. When issued, the other party members try to defend whenever they can; they have cooldown timers for their Defend actions too.

However, both commands do have cooldown timers, but they are not shown to the player. Therefore, the player has to be careful with these too.

If the player issues the defend command at the right time and have the currently-controlled party member take a defend action, the entire party can weather an incoming attack that would have otherwise floored them.

GAMEPLAY PAUSES DURING COMBAT:

To help the player keep pace with the progression of combat, there are certain control inputs that pause the gameplay. Switching characters, selecting targets and selecting spells or items to use cause pauses, to cite some examples.

However, cycling through the dial menu that lists the major actions that a character can make does not pause the gameplay. This can seem annoying, especially considering that the other actions that require deliberation on the player’s part would pause the gameplay.

DRIPPY’S AID:

In the original DS version of the game, Drippy is a full party member, specializing in fairy magic. However, in the Wrath of the White Witch remake, Drippy’s contribution to battle is much reduced, for better or worse.

Drippy’s only contribution to battle is a powerful buffing and healing spell that might trigger when the party is badly mauled. The game apparently uses the averaged hitpoints of the party to decide when this happens. Drippy’s spell imparts considerable healing and bonuses to the defense stats of party members. Unfortunately, he cannot bring back downed party members.

ERRANDS:

Present-day RPGs with overworld elements often have a multitude of quests for the player to pursue. Ni No Kuni is no exception.

Thanks to the Swift Solutions franchise, the people of the world can register tasks and requests at the Swift Solutions branch offices, which adventurers can visit in order to know what good deeds that they can do for the world.

At least, that is the narrative excuse for giving the player the means of finding whether there are any quests that can be pursued. There are certain quest-givers that could not possibly register errands at the branch offices, e.g. ghosts that non-magical people cannot see, but then, video game logic has always been problematic.

Anyway, looking at the board of errands at the offices only informs the player of the existence of quest-givers. The player still has to have the party reach the quest-givers before being able to embark on the quests.

As for the quests, if there are multiple stages, each stage of the quests has its own writing. The player might want to read this, because it contains reminders on what the player needs to do.

Most of the quests are quite simple. The party has to reach someplace somewhere, and then fight and/or retrieve something. Some quests are as simple as casting the right spell (usually from among the aforementioned virtually unused ones). Of course, more than one of them involve a fight, though these are not really difficult and may even be laughably easy.

RIDDLES:

The more troublesome errands are those that involve riddles. Some of the mandatory quests have these too. An unmarked optional quest-line also has doles of these.

Some of the riddles are posed as hints, such as those of the unmarked quest-line. In the case of these, it is a matter of using one’s logic to either search for tell-tale clues or to eliminate the improbable.

Some of the riddles are part of puzzles that require the use of the Puppet Master spell, which is only ever used for these puzzles. That said, some of these puzzles have red herrings that can be dastardly.

SEEK FORTUNE SPELL:

After the player has progressed significantly in the playthrough, Oliver gains the Seek Fortune spell. This spell reveals something that the new player might not have known until that point; there are invisible chests on the overworld.

These chests can be interacted with, just like chests that the player can see. The main difference, other than these chests being invisible, is that they do not have any collision hitboxes. This means that the new player might just have a party move past an invisible treasure chest without knowing it is there.

Using the aforementioned spell reveals the locations of the invisible chests on the regional map. Therefore, the player will need to look at both the party’s location on the overworld and the regional map in order to locate the spots where the chests are. Generally, they are often found at nooks and crannies, though some of them are located at dastardly ambiguous locations, such as the edge of the cliff or the immediate bottom of the same cliff.

When the player character is next to the invisible chests, an exclamation mark appears over his head. However, this only happens if the spell is active. Still, if the spell is not active, the player can have an invisible chest opened anyway if the player is sure that the player character is next to it.

Eventually, the player might find that traipsing on foot is too slow, and the Travel spell puts the party nowhere near any of the chests. The invisible chests are always located on land, so the ship is not of much use. This leaves the flying ride, which does help a lot in cutting down travel time.

Unfortunately, this just reveals another design issue. When the party is on the flying ride, the player cannot see the regional maps. The player can only see the world map, which does not show the hidden chests.

CASINO:

For whatever reason, Level 5 decided that including a feature about gambling would be a good idea in a game that is supposed to be family-friendly. (The inclusion of this feature also bumped up the age ratings of the game to early teens.) The casino becomes available to visit halfway through the playthrough.

Of course, there are no microtransactions to be had in this feature, much less any use of real money. However, the mechanisms of two of the gambling games in the casino very much follow their real-world counterparts.

These are the slot machines and the blackjack table. These follow rules that would be familiar to people who have experienced these relatively simple gambling games. This also means that they are the most fickle games at the casino.

Then, there is “Platoon”. This is supposedly a game about strategy, because both players are allocating cards to stacks that will be pitted against each other. However, the luck of the draw is a significant factor anyway; the player could be dealt a hand that is very poor compared to that for the CPU-controlled opponent.

The only game at the casino that is not luck-dependent is “Double Cross”, which has the player controlling the movement of two player characters simultaneously. This game is based on a certain mandatory challenge in the main story, albeit expanded further with additional levels.

To briefly describe this game, the two player characters have to navigate an obstacle course while staying ahead of collapsing tiles.

This can be daunting to a single player, especially if he/she is using a controller. On the computer version of the game, the player can use the WSAD and arrow keys, which make for easier gameplay especially if the player is ambidextrous.

The player can have another person help; this is perhaps the only part of the game that sort of supports multiplayer. Of course, the single player can still persevere on his/her own. After all, the levels in Double-Cross are fixed, and thus can be memorized.

The objective of the player is to win enough chips to redeem for prizes. This is easier said than done, because entry into any of the games requires an entry stake (and much more so for the slot machines, of course).

The prizes include some items that are very hard to find elsewhere. The prizes also include tickets for familiars that are not encountered elsewhere.

POST-GAME:

After the player has pursued the main storyline to its conclusion, the game prompts the player to make a post-game game-save. Making it and reloading it later unlocks the post-game content. The post-game content contains some of the most arduous quests, most obtuse riddles and such other “challenges”. The player’s reward is generally powerful gear pieces, a spell that has yet to be obtained and more lore on the backstory of the game.