INTRO:

In fantastical stories, the wizard is an individual who is said to have tremendous arcane might.

However, in video games, the wizard is usually no more than a glass cannon. Moreover, as powerful as his/her spells are, there is always some limitation which prevents a player from simply spamming spells, be it limited mana reserves, cool-down times or the need to “memorize” spells (which the Dungeons & Dragons franchise is famous/infamous for).

Magicka tosses out a lot of these limitations, allowing for free-wheeling casting. It does the latter via a surprisingly simple to use yet deceptively sophisticated system of mixing spell components before unleashing them.

There are more nuances than just these, if one could look past the so many icons which depict premium DLC.

PREMISE:

Despite the screenshot above, Magicka does try to tell some stories.

Its first story is about hooded wizards who set out to save a fantastical world – yet again – from its perennial troubles. The story is mainly an excuse to throw monsters at the player for him/her to fry, electrocute, freeze or just beam to bloody chunky deaths.

The first story does make use of any moments to pan a lot of tropes about fantastical wizards, as well as make fun of video game designs concerning wizards too. However, some parts of its humour might be too over-used to stand the test of time; there will be more elaboration on this later.

The other stories similarly parody a lot of things. However, they are placed behind pay-walls.

MOVING AROUND:

The first thing which the player will learn to do in the game is to move his/her wizard around. There is no in-game tutorial for this, probably because the developers thought that this is so easy that any player could do it.

Anyway, moving the player’s wizard is a point-and-click affair: the player clicks somewhere on-screen and the wizard tries to go there.

Unfortunately, the wizard’s pathfinding script is deficient. If the stretch between where the wizard is and where the player is directing him/her to go to has an obstacle, the wizard gets caught on it. The player will have to manually direct the wizard around obstacles.

(Incidentally, this stupidity is rarely exhibited by enemies in the current build of the game.)

EXAMINING THINGS & CHATTING WITH N.P.C.’S:

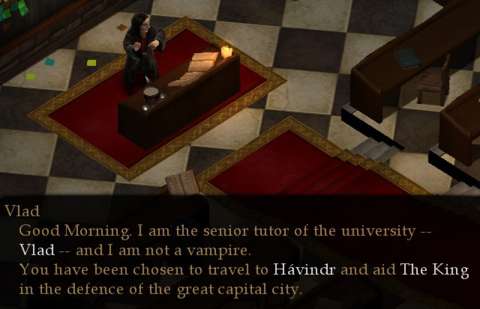

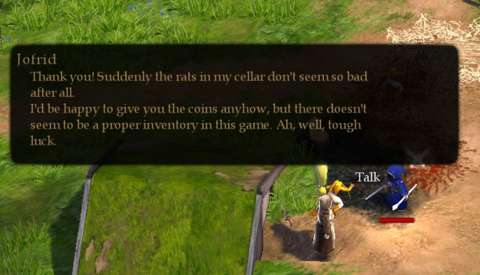

Magicka is a game about unleashing sorcerous power on fools and watching them blow up spectacularly; it is not a game about checking the details of objects or talking to people.

Nevertheless, the game does give the player an opportunity to do this – if only to make fun of itself and lampoon expectations about the game.

PREPPING SPELLS WITH ELEMENTS:

Casting spells is the most sophisticated and engrossing aspect of Magicka’s gameplay. However, it is not as simple as pointing the mouse cursor somewhere and pressing a button.

The player’s character starts with knowledge of the “elements” for spells right from the start. “Elements” are treated like components of spells, not as categories of spells as some other fantastical games do.

In order to cast spells, a wizard has to prepare some elements for the spells. The elements which have been prepped are shown in the bar underneath the wizard’s model. If the permutation of elements is viable, a spell can be cast.

At first, this may seem like a lot of busywork, especially to players who are used to setting up hotkeys for spells. However, this is actually a warranted limitation, because wizards in Magicka do not have any conventional limitations such as mana reserves and cool-down times. This – sort of – acts as the limitation instead.

Yet, there is the nuance that the permutations of elements do not merely determine what spell would be cast. The elements which are used also determine the strength, range and duration of the spell, among other things. A very simple example is shown in the following screenshot.

There are also other nuances, such as merging the Water and Fire element into the Steam element (which can be sprayed like wholly Fire element spells, but they injure fire-resistant enemies too).

If there is any limitation with this system, it is that some different permutations still result in the same spell. To elaborate, this is due to certain elements having precedence over other elements when it comes to deciding what properties a spell would have.

For example, the projectile effect of the Rock element will always take precedence over elements which grant a spell spray effects (such as Freeze and Fire). As another example, the Shield element takes precedence over everything else, meaning that any of the player’s spells which contain a Shield element will always be a shield-, barrier- or mine-creating spell.

The convenience of setting up spells by merely queueing up elements and the lack of any limits such as mana costs can seem to make a wizard all too powerful for gameplay balance.

Yet, there is indeed a disincentive to abuse the system. Stacking up elements slows down the player’s wizard, so having some elements prepared all the time is not a viable strategy.

This also means that the player must quickly decide what spell to cast during a fight; having a slowed-down wizard is not a good thing.

DEFAULT SPELLS:

Without any elements queued, the wizard’s spells are limited to either air-blasting or that provided by his staff.

When casting offensive spells without any elements, the wizard creates blasts of air instead of elemental spells. These not only damage enemies (albeit the damage is small), but more importantly, toss them away from the wizard. This will be incredibly useful in forcing enemies into hazards.

When casting spells onto the wizard himself/herself without any elements, the wizard makes use of the staff’s special powers. These powers generally cannot be replicated through any spell. For example, there is a staff which can summon a tree monster (“ents” to those who admire Tolkien’s works).

However, these staff-derived powers have cool-down timers, which are not exactly shown clearly to the player. (There is an audio cue though.)

MAGICKS:

Any wizard comes already well-equipped with knowledge about the elements and how to combine them to create defensive and offensive spells. Yet, not every wizard knows every spell (which is a fact which will be used for some laughs in the Adventure campaign).

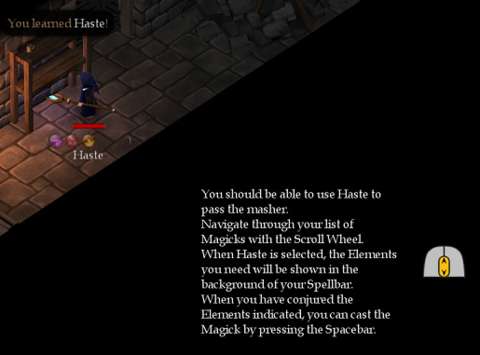

Some spells – known as “Magicks” in-game – can only be learned by retrieving spellbooks which are scattered around the levels in the game; the player is shown a counter of how many have been retrieved when selecting a save-slot to load. After obtaining the spellbooks, the player can cast these spells by queueing up the elements which are needed for the spell.

There is a small problem with Magicks though; the elements must exactly match the requirements, e.g. the correct elements must be in the exact arrangements.

Considering that other spells do not have such a limitation, this can seem an annoyance.

As for the Magick spells themselves, some of them are buff and de-buff spells. For example, there is the “confuse” de-buff, which as its name suggests, messes with enemies’ priorities.

However, these buff and de-buff spells are seemingly only there to tick off check-boxes in typical spell designs. In practice, they are very difficult to use efficiently during battles. After all, the (short) time spent to accumulate the elements for Magicks could have been spent on actual offensive spells.

Some Magicks are sorcerous shenanigans. For example, there is Rain, which does not help much. It may douse widespread fires, but it lasts for so long that its impediment to fire and lightning spells are very much unwelcome. An even more unreliable Magick is Thunderstorm, which sends lightning bolts hitting all over the place.

Some are even jokes. For example, there is “Crash to Desktop”, which causes any random character on-screen to simply die. Of course, one can argue that this is the developer’s apology of sorts for the game’s terribly buggy launch version.

However, it can also be seen as cheeky and insincere. This further strengthens the impression that most Magicks are unreliable and not worth the opportunity cost of casting spells which directly affect enemies.

(By the way, the only unanimously worthwhile Magick is Teleport.)

TURNING SPEED WHEN CASTING SPELLS:

A wizard in Magicka may be able to cast spells without care for cool-down times, mana costs and such other limitations which hobble other, pathetic wizards. However, there are subtle nuances which compensate against this advantage, one of which has been mentioned earlier.

Another nuance is that different spell properties also have different drawbacks and strengths. For example, spray spells are short-ranged, but the wizard can turn around relatively quickly to harm multiple encroaching enemies.

SHIELDS, BARRIERS & MINES:

As mentioned earlier, using the Shield element always results in defensive spells.

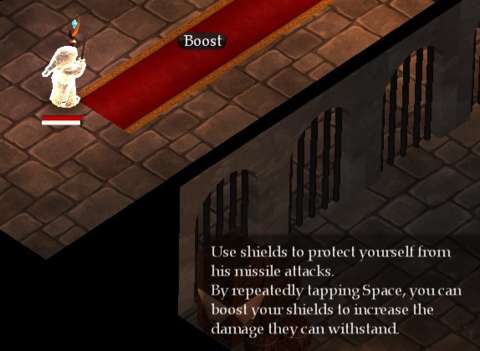

The vanilla Shield spells are the quickest to deploy, but they are also the least practical. This is mainly because the strength of these spells is governed in a different manner. This will be described for each individual permutation.

When used on its own, a Shield element creates either a shimmering layer of energy on the wizard, or a curved shimmering barrier which blocks any incoming attacks. Both have to be maintained by mashing on the spacebar button, which can be tedious. Although both types of vanilla shields can absorb any kind of damage, they do not last long.

The personal shield will not stop a wizard from being knocked down or tossed around either. The barrier shield is even less useful. While it does block attacks from enemies, they also block the wizard’s spells. At best, it is only useful as a magical wall of sorts, because it also happens to block enemy movement (whereas the wizard can pass through it, though doing this is rarely beneficial).

There are few scenarios where either vanilla Shield spell is useful. Even then, these scenarios may feel contrived. For example, there is an enemy which can be defeated by placing a barrier in its path when it attacks.

Instead, shield spells are far more useful when combined with elements. When used with the other elements, Shield-powered spells can be used in two ways: casting them unto the wizard so as to grant him/her an element-specific shield, or casting them unto the ground as mines.

For example, the player can combine the personal shield with the Rock element, essentially making the wizard impervious to most weapons. It also prevents the wizard from being knocked around too. The benefits far outweigh the spell’s drawback of slower movement.

Elementally-charged personal shields also render certain enemy attacks unusable. Returning to the example of the Rock Shield, it renders the Snow Troll’s instant-death chomp useless because it cannot pick up the wizard in the first place.

Combining a Shield element with a non-Rock element and then casting it unto the wizard grants him/her temporary immunity against that element. Alternatively, the player could do something stupid, such as granting the wizard immunity to healing.

(There are Wizard variants which are damaged by healing of course, but that is another matter – specifically a matter of premium DLCs.)

If there is a major issue with personal shields, it is that the game does not mention which shields block healing. The vanilla shields and Rock Shield certainly do, but the non-Rock elemental ones do not.

Barriers are especially customizable with other elements. The best example of this is that Rock and other elements can be used together with the Shield element to create barriers which also have their own auras.

Mines are placed into the ground. Only human players can see them, whereas enemies cannot. Anything can trigger mines, however. If enemies move into them, they blow up. If the wizards get tossed onto them, they blow up. If area-effect spells hit them, they blow up.

Ostensibly, the player can try to mine an entire area and lure enemies into them. However, due to the camera not being in the player’s control, not running into them when retreating can be difficult. Furthermore, they are rendered useless if the game decides that the player cannot backtrack to earlier areas.

Laying down mines in the path of pursuing enemies while being pursued is also risky. Some enemies can move faster than the rest, so the player runs the risk of these enemies triggering the mines when the wizard has not gotten clear of them.

STAFFS:

Although Magicka tossed out many typical tropes about the wizard archetype, it does retain some of them. One of these is the wizard’s staff.

Anyway, at any one time, the wizard has only one staff in his/her left hand.

As mentioned earlier, the wizard’s staff determines what kind of spell which he/she can cast on himself/herself when the wizard does not have spell elements queued up. Most staffs offer buffs.

However, there are some staffs which fire off offensive spells instead, usually at where the player is pointing. Yet, these spells are just not as powerful as those which the player can cook up. Coupled with the cool-down timers for these staff-derived spells, they are generally not practical for combat.

Staffs do have a greater benefit to offer though: passive buffs. These are usually useful. For example, the Staff of War grants a buff which doubles the wizard’s hitpoint reserves.

However, some of these buffs are double-edged. For example, the healing aura of the Staff of Life heals anyone who gets into the area of affect, including enemies.

Staffs are usually obtained from the environment. For example, the Staff of Life is often found standing among farm crops. Some others are obtained as rewards for uncovering secret areas.

WEAPONS & ENCHANTING:

Wizards using steel-wrought weapons are nothing new, so Magicka would not surprise any experienced player when he/she learns that that a wizard can wield a sword or something similar.

Yet, the wizards of Magicka are not martially-inclined people. Regular attacks which they make with their attacks are at best wimpy, even if these weapons may have some additional properties such as being able to freeze enemies which they hit.

Considering that they can only hit one enemy at a time, resorting to weapons is usually a last-ditch affair.

To further expand their repertoire of spells, wizards can enchant their weapons such that they can unleased magically charged attacks. For example, a sword can be enchanted with Freeze elements so that a wizard can unleash a wide swing which can hit and freeze enemies.

This can be seen as a method to store offensive spells without the slow-down penalty. However, this is not exactly a good impression to keep in mind. This is because the spells have been altered after they have been applied as an enchantment.

To cite some examples, beam spells which have been used to enchant weapons lose their beam properties; the same occurs to spray spells.

The game will not inform the player about all these subtle differences though.

The third use of weapons is to block. However, this is only useful against individual human-sized enemies. If the wizard is being mobbed, it will not help much at all. If it has not been said already, keeping distance from enemies is generally a wise tactic.

M60:

The M60 weapon has to be mentioned here, mainly because of two reasons: it is thematically mismatching, and quite overpowered. It easily overshadows the other weapons because of its ability to pile a lot of damage over long ranges.

Of course, one can argue that it only occurs once in the main adventure, does not work against armored enemies (which become more common later) and can be easily lost. It also does not work well with enchantments (e.g. the bullets are not enchanted); when used to release spells, the M60 is used like a bludgeon instead.

RETAINING WEAPONS & STAFFS:

The games does not make it clear that the player’s wizard retains his/her weapon and staff from session to session, until the player customizes his/her wizard. When this happens, the weapon and staff reset to whichever robe which the player picks.

ROBES:

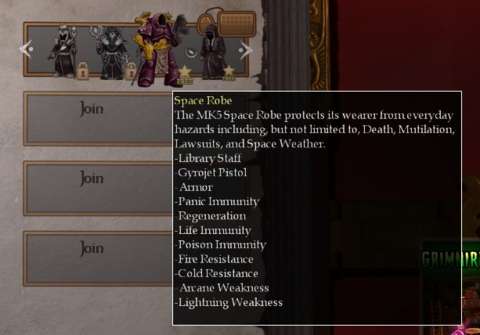

Speaking of robes, picking a robe is an important decision when starting any session; the player’s choice of robes determines the wizard’s starting weapon and staff. It also determines his/her passive resistances and other innate abilities.

Unfortunately, this is also where Magicka’s proliferation of premium DLC shows itself. Many of the robes are placed in premium DLC packages.

DROWNING & FALLING:

A wizard can die in more ways than one. However, two particular types of death stand out, mainly because of how inconvenient they are.

Wizards cannot swim, so getting into deep water causes them to drown. Wizards cannot fly either, so being tossed off cliffs is also undesirable. Either death would have been a comical setback, if not for the fact that a wizard’s staff and weapon are lost permanently when he/she goes out this way.

This can be a problem in multiplayer; the other players could have benefited from looting that wizard’s gear, or that wizard could be revived and immediately rearmed. It is also a problem in single-player when the player still has the fairy to revive his/her wizard.

Of course, a skillful player can still prepare for such possibilities, e.g. having a wall behind his/her wizard if he/she cannot stay away from enemies which can toss wizards around. Very quick fingers, e.g. casting Teleport quickly, also helps a lot.

FAIRY:

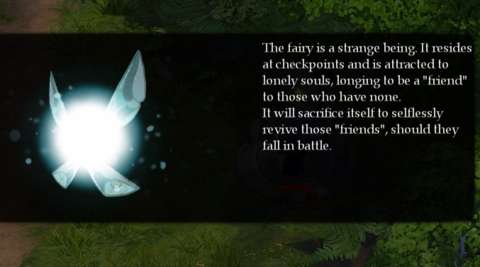

Speaking of the fairy, the fairy was a feature which was implemented later after the release of the game, supposedly to make the single-player experience a bit more forgiving.

Previously, the player is shunted to the previous checkpoint upon having the wizard die. The checkpoints can seem separated by one too many fights, but of course, one can argue that the player should have been careful in the first place. After all, the wizards in Magicka are not easy to kill and are walking magical death.

Anyway, the fairy has been implemented to mitigate this issue, in lieu of more checkpoints. When the wizard dies in a single-player session, the fairy sacrifices herself to revive the wizard on the spot.

However, it is a half-hearted, tongue-in-cheek measure. This is because the fairy can be incredibly annoying with its useless remarks.

(Fortunately, the fairy shuts up when the wizard is fighting.)

DEFICIENT PROGRESS RECORDING:

Magicka lacks a decent game-saving feature. Instead, it makes use of a checkpoint system.

The checkpoint system would not have been an issue if not for the considerable number of fights in between checkpoints.

The game also does not make it clear that there are checkpoints which are not the usual monuments. These checkpoints tend to occur at the start of another stage of a level.

(LACK OF) TARGETING ACROSS DIFFERENT HEIGHTS:

Although the player can target seemingly anything around the wizard with the mouse cursor, the wizard’s spells can only hit objects on the same plane of height. Anything below or above the wizard cannot be hit, and the wizard will not adjust his/her aiming.

The game could have been better if there was more contextual targeting, e.g. aiming scripts which are based on the distance and angle between the wizard and his/her target, but there does not seem to be any.

This limitation becomes a major problem when fighting in craggy terrain, such as the later chapters in the first adventure campaign.

INVISIBLE WALLS & NO CONTROL OVER CAMERA:

Before elaborating on the issue of invisible walls, it has to be said that Magicka is not pretending to be an open-world game. It is more akin to twin-stick shooters.

Hence, it may seem understandable that it would hem the player into a limited area during a battle. However, this limitation is not always applied to every battle.

Some battles allow a wizard to backtrack to earlier locations. Some others place invisible walls at the edges of the screen and fix the camera to a specific location. In these cases, the limitations are there to impose an artificial level of challenge, which may not please every player.

It is not always clear which places the wizard can go to and which he/she cannot either. Sometimes, the wizard can go behind a large object (relative to the view provided by the camera), such as large rock. At other places, the wizard cannot go under what appears to be an overhang.

ENVIRONMENTAL HAZARDS:

If it is not apparent already, there are many things which can kill a wizard, and these are not necessarily hostile creatures or sentient ones.

More often than not, environmental hazards will account for a considerable number of wizard deaths – even players who are skilled at the game would find their wizards tossed into something dooming once in a while if they get careless.

Of course, such statements are nothing remarkable; Magicka does adhere to typical hazard design tropes, such as the “lava level”. What makes the environmental hazards in Magicka remarkable though, is how the player is given the means to get out of them.

The Teleport Magick, in particular, is a life-saver. For example, when executed during the scant few seconds before a fatal fall, the wizard is teleported to the closest ledge. In another example, the drowning animation for a wizard caught in water lasts a few seconds; the player can attempt to quickly cast a teleport spell, though the convenience of being teleported somewhere safe is not there.

NPC ENEMIES:

Most of the computer-controlled enemies which the player will have to eliminate are typical fantastical monsters and vermin, such as trolls and goblins. Some others are wizards. There are also a few legendary creatures (and thus these are typically bosses).

Magicka does follow some good design conventions for enemies, and some stale ones too.

An example of a good one is that almost every enemy which looks different from the others has its own capabilities in combat. A more specific example of this is that regular goblins lope towards wizards, whereas goblin archers prefer to use their bows.

Yet, similar enemies also have common abilities to keep in mind. Returning to the example of the goblins, any goblin is capable of jumping onto a wizard and beating on his/her head. This includes the Goblin archer.

An example of a stale one is that Magicka does resort to palette-swapping. A more specific example is that goblin miners function no differently from regular goblins.

Regardless, most of the enemies in the game are only there to show how awesomely powerful wizards can be – and how fast they can die if the player just does not learn quickly enough how to counter them.

ELEMENTAL WEAKNESS:

Some enemies happen to be vulnerable to specific elements. This is generally clear to players who are experienced with rock-scissors-paper gameplay elements, especially the fantastical ones.

For example, creatures who are wearing armor may be well-protected against weapons, but they are still vulnerable to lightning attacks.

Usually, the game will give overt tips on spotting them. This is sometimes provided through the loading screens (though the loading screens might also give nothing more than useless prattle). For example, the game will point out that water does not mix well with electricity.

Some enemies make this observation even easier, usually through colour-based cues. Each element is associated with a colour after all; for example, the purple colour is for lightning. This is a cue for the player to use the water element, which is associated with the blue colour.

(Incidentally, pure water spells can only damage such enemies.)

GRAPPLES:

There are a few enemies in the game which can grapple wizards; the consequence which follows, if the player does nothing, is usually a lot of damage or an outright, messy death for the wizards.

This may seem cheap at first, but observant players would notice that wizards which are being grappled can still cast spells. Teleporting out would be wise.

(Of course, the player is given the prompt of “breaking free”, but this is an inefficient way to overcome grapples.)

Alternatively, the player could turn the grapple into an opportunity. After all, enemies who are grappling wizards stand quite still. Thus, in multiplayer, other players can line up powerful shots (saving their peer is really a secondary matter). Even the wizard who is being grappled can fight back by casting spells point-blank.

FREEZING:

The Cold element can be worked into spells to grant them the property of slowing down targets, if they are not immune to the cold.

Frost-covered enemies perform their animations a lot slower. This sets them up for slow but powerful spells, such as the devastating boulder which can be shot like a cannonball after charging up a five-Rock-element combination.

Of course, freezing enemies to slow them down are nothing new in video games, of course. However, it is a lot easier to perform in Magicka than in many other games, in which such spells tend to be considered too powerful and are “balanced” with a lot of setbacks.

Unfortunately, the notable designs about the mechanism of freezing happen to be problems instead of nuances.

One of these problems is the supposed synergy between water and the cold. When used together, this results in much quicker application of the slow-down effect. In fact, some enemies can be frozen solid with these spells, rendering them immobile.

Yet, the issue here is that freezing effects which have been augmented by water dissipate very quickly. Perhaps this was intended for purposes of gameplay balance, but they go against believability.

DAMAGE SPONGES:

For better or worse, there are enemies which are nothing more than damage sponges. They do not have clear elemental weaknesses, either. More often than not, they were introduced as bosses (in the early levels of the Adventure campaign), and eventually become mini-bosses.

Trolls are the most representative of such enemies. They are mountains of hitpoints which also happen to heal rapidly. The only reward which the player gets from killing them is their elaborate death animation – which is shared by just about any troll, regardless of their sub-archetype.

There are indeed ways to kill them quickly, but this requires getting rid of other enemies before dealing with the trolls, mainly because these methods take time to set up.

For example, some of these methods involve multi-element spells which require a lot of input before they can be cast. Even then, they require time to charge, or otherwise the resulting spell is so weak that the trolls shrug them off.

USING THE ENVIRONMENT AGAINST ENEMIES:

Some of the most entertaining moments in Magicka are when the player figures out how to use hazards against enemies.

Some of these have been implied already; getting enemies wet by having them cross rivers before electrocuting them is very satisfying.

The best ones though are those which inflict outright death on enemies. An example is shown below.

HOSTILE WIZARDS:

The player will not be the only one who gets to wield sorcerous, army-levelling powers. There are enemy wizards who are controlled by the computer. They have no issues with flaunting their magical might.

In fact, they are incredibly reckless with their spells. Sometimes, they may do silly things, like firing healing beams at allies, only to miss and hit the player’s wizard instead. At other times, they are very vicious, spamming their most powerful spells with wild abandon.

Indeed, if the player is not careful, these wizards can easily ruin his/her day. However, these wizards also happen to share the same weaknesses as the player’s wizards; these can be exploited. For example, it is easier to eliminate a wizard by pushing him/her off a cliff.

MULTIPLAYER:

Magicka is designed with multiplayer in mind (if the recently released Magicka Wars does not suggest so already).

The “Online Play” lobby feature gives the player a browser to look for sessions, probably using Steamworks’ facilities in the case of the computer version of the game.

The vanilla package of Magicka grants the player the following options: playing the Adventure campaign with other players, a survival mode which pits endless waves of enemies against the players, and fighting against other players.

Of the three, the third one, “Versus” mode, is the least developed. This is mainly because of the developers’ shift of focus to the “free-to-play” Magicka Wars. This is unfortunate.

Challenge mode only has two maps in the vanilla package of Magicka; the bulk of the maps for the game is locked behind premium DLC.

CO-OP:

On paper, playing with other players grants opportunities for some powerful co-operative attacks.

Some of these are unique to multiplayer: for example, two players can fire beam spells and cross them together to create a powerful combined beam, if the beams are compatible. If they are not compatible, the result is a very powerful explosion.

In theory, this crossing of beams can be used to quickly annihilate groups of enemies. However, they require a lot of coordination; it might be easier for players to just stay clear of each other’s line of fire and duplicate each other’s spells as the situation dictates. A barrage of similar spells can have the same results with less hassle anyway.

The only truly useful benefit of playing in co-op is that healing spells are much more effective when used on other wizards.

The greatest caveat of playing co-op is that friendly fire is always turned on. This can seem irksome at first, especially if the player has the misfortune of having to play with mischievous or incompetent people.

However, in hindsight, this was perhaps an understandable drawback, considering how powerful wizards are. Indeed, a well-coordinated team can blow through the Adventure campaign very quickly; if they did not have to worry about friendly fire, they would be even faster.

REFERENCES & MEMES:

For better or worse, much of the writing seen in Magicka makes use of references to so much popular culture, including memes.

At first, they might elicit a snicker or two, such as the spoofing of fantastical story tropes which occur early in the Adventure campaign.

However, the rest of the humour from the game is groan-/cringe-worthy.

Many of the loading screens, descriptions for items and magicks, presentation of secret areas and names of achievements are influenced by Internet memes. For example, there is a loading screen which mentions Chuck Norris, of all celebrities to mention.

Such kind of humour might have been popular when this game debuted (2011), but after years of so many games with such humour, it is stale now – except for those who are endlessly amused by such things of course.

VISUAL DESIGNS:

It is worth noting here that a year or so after the release of the game, Magicka had been updated in order to overhaul its artwork, especially for the environments.

However, the character designs remain the same, perhaps for the better.

All wizards still look heavily hooded, their faces all but undiscernible. Other humans (if the wizards are indeed human) appear to look a bit caricaturized and also unremarkable when compared to the wizards.

The enemies are a lot more interesting to look at than the NPC humans. Almost every creature – discounting palette swaps – have its own set of animations, making them easy to discern when they are bunched together.

The most impressive visual effects are those for spells, of course. Watching fire, steam or water spray from wizards’ palms and ruin enemies is satisfying. An even more satisfying example is watching a fully-charged pure-Rock spell spitting forth a boulder which obliterates multiple enemies, leaving craters and chunks of red wherever it bounces.

SOUND DESIGNS:

For better or worse, some of the music tracks in Magicka are slightly influenced by known classics, such as the tracks for Legend of Zelda; these tend to play at places where the aforementioned references are made too. Fortunately, the other tracks, such as those which play during combat, are much more original.

Most of the sound effects which the player would hear from the game are the sounds of spells inflicting painful deaths on their victims.

Perhaps the second-most satisfying noise to be heard is the charging-up of spells and the tinkling of spells having reached full power. (The most satisfying noises are of course those which come next.)

Most of the voice-overs in the game are illegible mixtures of distorted Swedish and English. They are not very memorable, but the subtitles which comes with them (always turned on by default) are at least hilarious to read.

The best voice-acting in the game is the only one which is legible. This is not a bad thing though; it would be difficult for Vlad the not-vampire to fail to entertain the player with his narration.

PREMIUM DLC:

Unfortunately, Magicka is one of those games which succumbed to the temptation of making premium DLCs after its debut.

Additional adventures are priced DLC. Some maps for game modes like Challenge are packaged in priced DLC. Alternative robes for wizards are also in these priced DLC, among other annoyances which are labeled with padlock-shaped icons.

Worst of all, when the player is within the main menu screen, the bottom right corner of the screen is always filled with a product pitch. (This is an unseemly trend in Paradox Interactive games.)

It has been so long since the debut of this game (three years at this time of writing). There is that, and Magicka 2 is being developed. Yet, whoever has the rights for this game has not deemed it fit to consolidate every piece of content for this game into a heavily discounted package at the end of Magicka’s product life-cycle.

Magicka is not exactly a Paradox Interactive property, but it contributes to the impression that Paradox Interactive’s products have a tendency to be tainted with post-release nickel-and-diming.

CONCLUSION:

Magicka is far from an excellently designed game. There is “joke” content with near-worthless practicality in terms of gameplay, such as the Magicks. There is also a lot of humour which has not aged well. There are also a few technical limitations which inconvenience the player. Worst of all, much of the content for Magicka is behind paywalls, even though it has been years since the game’s release.

Regardless, these are minor hiccups which do not detract too much from Magicka’s main appeal of unbridled sorcery. Its very convenient system of spell-casting feeds fantasies of wizards who can spam spells without regard for magical restrictions.