INTRO:

Sometimes, someone has an idea which he/she thinks is brilliant, though it is not guaranteed to be so.

One such idea is a method to make play sessions brisk, but implementing it in what is practically a board game turned into a digital game. An example of this kind of idea has resulted in Greed Corp, a game which has since been made for many platforms due to its apparent simplicity.

PREMISE:

The fictitious world in which Greed Corp takes place in is very much screwed, and that is an understatement. The people of this world has somehow learned to harvest the mineral wealth of their world, straight down to the core from its surface. Predictably, the technology has ruined their world, destroying the outermost crust of the planet and causing entire continents to crumble into the ominous dust clouds below.

Anyway, whatever stable land which remains on this world is fought over by four factions.

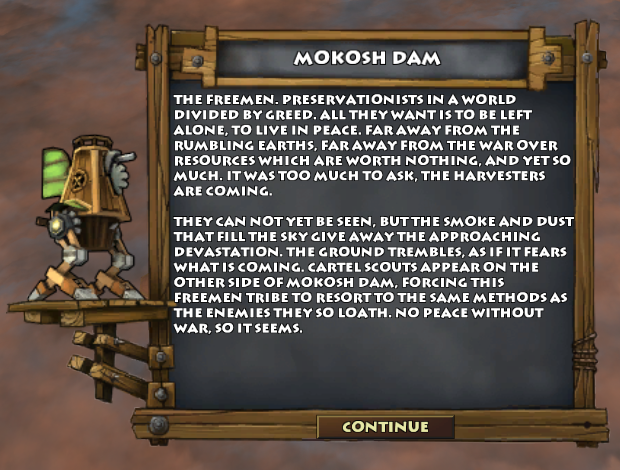

There are the Freemen, a supposedly environmentalist society who has no issue sacrificing a few bits of land here and there to save the rest from the other factions, for the sake of “future generations” of course.

Then there is the Cartel, who is perhaps the most exemplary of the name of the game itself. Being a conglomerate of typically avaricious corporations, the Cartel is the most ardent user of the aforementioned technology.

Next, there is the Empire, which is perhaps the most hypocritical of the lot. Confident in their belief that true order in the world lies with them, they are more than eager to just sweep any opposition away – even if the price is whatever remains of the world.

Finally, there are the Pirates, who are treacherous and rather carefree about the state of the world. They steal from everyone else and scavenge technology instead of designing it themselves.

The game offers a campaign for each faction, if only to depict their ideology. Gameplay-wise, they are fundamentally the same.

GIST OF GAMEPLAY:

The gist of the gameplay in Greed Corp involves managing territory and assets, while trying to diminish those of the opposition.

Such gameplay is nothing new of course. However, Greed Corp injects a caveat into the gameplay: nothing which the player has can be held on for long. The same caveat applies to his/her enemies.

This is due to the need to sacrifice precious land in order to generate the resources needed to take the lands of enemies, or deny them to enemies if the player does not have enough resources for a take-over. Eliminating the assets of enemies also means destroying the land on which they had been placed.

Therefore, the gameplay experience of Greed Corps tends to be quite tense, as players try to outmaneuver each other while the playing field crumbles all around them. As time goes by in a match, the players’ (already limited) strategic options are reduced while they go on a scramble to make sure their enemies go out before they do.

Such an experience goes some way to offset the creeping boredom caused by the lack of technical complexity in the gameplay of Greed Corp.

GAINING TERRITORY:

The territory which players will fight over are represented as hexagonal tiles, each of which sits on top of a column which depicts its remaining “layers”. There will be more on layers later.

Gaining territory is an essential component of any strategy. Without doing so, the player cannot gain the ground necessary to launch attacks against opponents, check their advance or gain any additional income.

To gain territory, the player needs to field and move “walkers” around. Walkers appear as armed bipedal robots, but they are actually little more than simple game-pieces to be moved about. Furthermore, the walkers for any faction are the same as those for any other faction. This can seem like a lost opportunity to make the game more sophisticated.

Anyway, uncontrolled territory is depicted as pristine prairie land or light forest. When at least one walker of any faction is moved onto a tile of uncontrolled territory, that tile’s appearance changes in order to reflect the faction’s just-acquired ownership of that tile. For example, having a tile captured by the Freemen changes the tile so that it appears to be covered with farmland.

However, this is just for the start of a match. Afterwards, this captured territory is to either exchange hands more than a few times or to simply crash into the abyss from over-exploitation, outright bombardment or “scorched-earth” tactics.

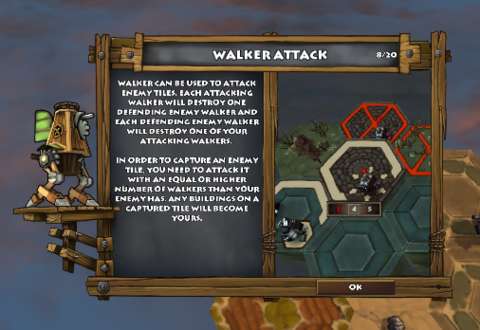

Territory exchanges ownership when the attacker attacks a tile owned by another faction with a stack of walkers equal or greater than the defending stack. Even if the numbers of the opposing stacks are equal, the attacker wins by default; in this case, the tile changes ownership, but it is, of course, undefended and vulnerable to a swift counter-attack in the next turn.

If an owned tile is devoid of any defenders, it is obviously taken over, even if the attacker sends just one walker.

To control the rate of territorial gain by any one player, there are rules to making advances on unclaimed territory and territory which has been claimed by the enemy. The most important rule is that advances can only be launched by walker stacks from adjacent tiles, and the stacks must not have moved from the start of the turn.

This means that any player who happen to have a large number of stacks cannot go on a territory-taking blitz; his/her territory can only expand by one tile in terms of range in any turn.

SHIFTING WALKERS WITHIN TERRITORY:

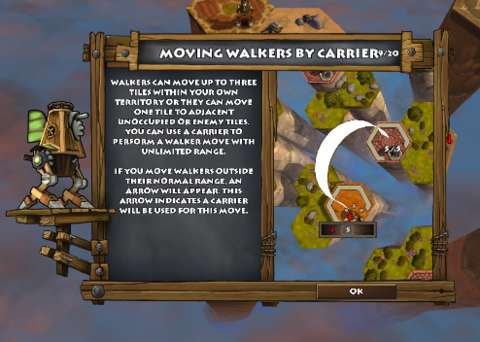

Walkers are likely to be created within the player’s territory, far away from the front-lines (for a reason which will be mentioned later). Therefore, these walkers are given the ability to move up to three tiles within the player’s own territory.

Any movement taken, regardless of the tiles covered, is final for a stack though; if a stack has merely moved one tile, it cannot move another two.

DISTRIBUTING WALKERS:

Only one stack of walkers can be on any tile. Therefore, it is in the player’s interest to distribute walkers about so that they can be where they are most effective (and that is usually away from tiles which are about to crumble).

Walkers can be stacked onto one another so that they can be moved as an entire stack. Some walkers can also be split away from a stack, usually in order to claim or attack multiple tiles.

A handy counter on top of each stack shows how many walkers in that stack still have moves, which the player can spend to bring them away from that stack.

However, there can only be a maximum of 16 walkers in any stack on a tile.

ARMORIES & BUILDING WALKERS:

Obtaining more walkers is an important part of many strategies, so the player has to build armories in order to build more walkers.

The act of building walkers can be a bit wonky though, especially to a veteran of strategy games. To do so, the player has to select the option to build walkers first, and then the armory to produce them with, instead of the other way around. Then, the player has to fiddle with a dial to select the number of walkers to produce; the keyboard buttons for numbers do not work for this, by the way.

The player also has to keep in mind the aforementioned limitation of stack sizes when having armories crank out walkers; if there is a stack on the tile where there is an armory, the armory cannot produce walkers beyond the stack’s limit.

Walkers which have been built in a turn cannot be used within that turn; they are only available for redistribution in the next turn. The same limitation also applies to armories; armories which have just been built can only be used in the next turn.

USING CARRIERS:

As a reminder, walker stacks can only move onto adjacent tiles if they are attacking or across connected tiles if they are moving within their own faction’s territory.

Therefore, if the tiles which the stacks are on are cut off from other tiles, the stacks ostensibly have nowhere to go. In another case, the stacks may have to go across a long sequence of tiles to reach the front lines.

For these scenarios, the player is better off moving stacks of walkers via carriers.

Carriers are aircraft which can carry stacks of walkers across considerable distances; essentially, carriers circumvents the limitations on moving stacks about. Each carrier can only carry one stack, so the player must be careful as not to waste carriers on small stacks.

However, carriers are expensive assets. They cost a lot to build, and the player can only have up to three on stand-by. Carriers can only be used on the turn after they have been built too.

MONEY:

As mentioned earlier, the four factions gain wealth by practically digging out the planet. In-game, this has been implemented as an entertainingly risky gameplay element. However, there is also a turn-by-turn influx of money, just to ensure that players can do something when their turns come up.

In some matches, this alternative form of income is not enough to achieve victory, so the participants must partake in some earth-shattering industry. In others, it increases with each passing turn, making players more reckless and thus making the matches more exciting.

Money which has been obtained can then be spent on building walkers, armories, cannons, ammo and other assets.

HARVESTERS HARVESTING:

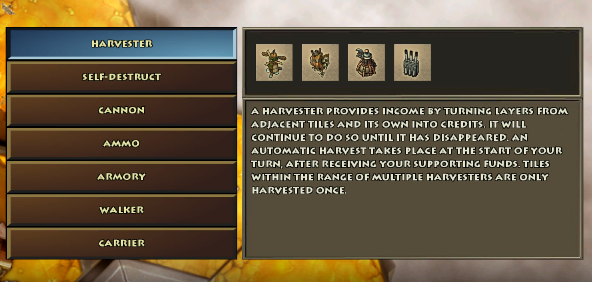

The main way of obtaining money is to thrash the land. To do so, players plonk down harvesters. At the start of any player’s turn – emphasis on “start” – the harvesters under that player’s control will take their due from the tile which they are on and the tiles around them.

Each harvester knocks off one layer from each tile, converting each layer into a few credits; there will be more elaboration on “layers” later. Anyway, this means the placement of each harvester is important, if the player wants it to pay itself off quickly and with a tidy profit. After all, harvesters have to be bought.

It is also important to note that a tile which is within the range of more than one harvester cannot be harvested more than once per turn. This seems a peculiar limitation at first, but it does prevent a cunning player from exploiting this gameplay element in order to affect the other associated gameplay elements.

SELF-DESTRUCT:

Interestingly, a harvester can be ordered by its owner to self-destruct. The harvester goes on over-drive and simply collapses, destroying its own tile and knocking a layer off adjacent tiles anyway, as if it has harvested.

The player does not obtain any money, however, so this decision is best made when losing the potential income from the tile(s) is a price worth paying for crashing a number of tiles which contain significant enemy assets.

LAYERS:

All tiles have different heights; this can be seen when the camera is giving an isometric view of the map.

However, the height differences will not be relevant to any gameplay element other than harvesting. For one, regardless of the difference of layers between tiles, stacks of walkers can move across the tiles without any issue; this can cause a bit of disbelief.

Anyway, layers indicate how much remaining wealth a tile has for plundering, before it crumbles away into the dusty mist below.

This might sound simple, but it is very important to keep in mind. Planning ahead is a very important factor in attaining victory, and planning ahead certainly includes keeping track of the number of layers.

Indeed, a cunning player – or computer-controlled opponent – can try to grab tiles which are adjacent to enemy-owned ones and then plonk down a harvester in an attempt to crash them, if they happen to be weak.

CRITICAL TILES:

Tiles which are reduced to just one layer left are considered to be in a “critical” status. These are depicted through changes in their appearances: the tiles become cracked, and the dots which depict the number of layers remaining turn red.

If a critical tile collapses due to self-destructing harvesters or cannon shell impacts (more on this shortly), any adjacent critical tile collapses; any critical tile which is adjacent to this also collapses, so on and so forth.

This means that if a player’s assets are placed on critical tiles, or are still on them, crashing one of the tiles through self-destruction of a harvester or cannon bombardment can lead to that player losing many assets in a single blow.

More often than not, players both human- and computer-controlled will make use of this gameplay element in the late stages of a match, often in desperation.

CANNONS:

The final significant gameplay element is the cannon.

Cannons are ranged weapons which the player can place on tiles. They are practically fixed artillery, but in some scenarios, they are more effective than walkers and carriers.

Anyway, after building cannons, the player has to purchase ammo for them in the next turn; the act of purchasing ammo is similar to purchasing walkers.

Then, the player has to wait another turn before said ammo can be used. These delays mean that the use of cannons has to be planned before they become useful, or else when they do become operational, the window of opportunity to use them has lapsed.

Cannons do have maximum and minimum ranges. Fortunately, these are shown to the player when the player is looking around searching for a tile to plonk down a cannon.

Interestingly, cannons are built on top of armories. However, this appears to be little more than a cosmetic effect.

Anyway, hitting a tile with a cannon shell causes it to lower by one layer. It also destroys a handful of walkers, if there is a stack of walkers on that tile.

ONLY ON THE NEXT TURN:

That stuff can only be used on the next turn after the turn in which they are bought is a statement which has been mentioned a few times already in this review. This is an important limitation, one that was wisely implemented by the game’s makers to prevent players from using what economic momentum which they have in order to outright steamroll the opposition.

Granted, this is nuanced gameplay-balancing, though whether it makes the game more sophisticated or not is debatable.

CANNOT SCUTTLE ARMORIES & CANNONS:

The player is not able to scuttle armories or cannons in any way. If they are captured, they immediately change possession.

At least the player who captured them cannot make use of these facilities until the next turn, so a wise player can still plan for counter-attacks. However, the player who captured them can choose to build things on them – specifically harvesters, which can complicate matters in later turns.

Perhaps the game could have been more sophisticated if there is the option to destroy armories and cannons. Without that, the player has to make do with the risky self-destruct option of the Harvesters.

CAMPAIGNS:

The single-player mode is a series of “campaigns” fought against computer-controlled opponents, to use that word loosely; the game certainly does.

The “campaigns” are little more than a series of matches with generally the same objective: eliminating all of the other players by destroying all of their assets or taking over all of their tiles.

Considering that the tutorials actually have special objectives (albeit these are geared towards teaching lessons), that the campaign matches do not have any other objectives can seem a bit disappointing.

Anyway, there is one campaign for each faction. There are some stories of sorts going on in the campaigns, but they are ultimately rather inconsequential to the gameplay. The game tries to emphasize the ideological differences among the factions through these stories, but gameplay-wise, it could do no more than display text which describes or hints at how many opponents the player would be facing in the next scenario.

As for the challenge of the campaigns themselves, they increase in difficulty, starting from the easiest, which is the Freemen’s, followed by increasingly more difficult campaigns, which are the Pirates’, the Cartel’s and the Empire’s, in that order.

To elaborate on their relative difficulties, the Freemen’s campaign grants the player unlimited time to make turns with and also pits the player against the lowest of computer-controlled opponents, the “Beginners”. (There will be more elaboration on computer-controlled opponents later.)

The other campaigns place limits on the time which the player can take to made decisions; the limits become more stringent with each subsequent campaign. The player also faces computer-controlled opponents of higher ranks.

‘CONQUEST’ POINTS:

Not all of the campaign scenarios are available from the start. Instead, only a few scenarios in the Freemen’s campaign are available for playing.

To ‘unlock’ the rest, the player must complete the available matches and earn what the game calls ‘conquest points’.

Any kind of completion will grant points; even defeat will grant points. If the player simply starts a scenario and then immediately quits, the player will not get anything of course. Performing better grants more points, of course.

The player cannot ‘farm’ already-attempted scenarios to accrue points though. The game will track how many conquest points have been gained from a scenario; to get more, the player’s performance must be better than his/her performance from the last attempt.

(Obviously, winning a scenario by being the last player remaining is considered as the “best” performance.)

COMPUTER-CONTROLLED OPPONENTS:

There are several different levels of aptitude for computer-controlled opponents, though these different levels are not exactly well-documented.

Generally, all of them seem to be decent in making decisions, and they make them quickly. However, Beginner-ranked opponents do appear to sometimes flub the placement of their assets, among other mistakes such as overlooking tactical opportunities such as not advancing on unclaimed terrain which is not going to be immediately contested by others.

Intermediate-ranked ones are less careless, whereas Expert-ranked ones rarely if not never make apparent mistakes.

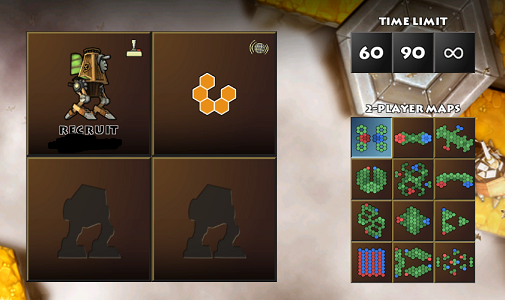

MULTIPLAYER MATCHES:

Greed Corp does have built-in features to facilitate multiplayer matches; specifically, they allow players to create lobbies with slots open for human players, who can use the same features to search for such lobbies.

Alternatively, the player can fill slots with computer-controlled opponents, if the player is looking to fulfill a minimum number of participants for a match.

After all, the variety of maps which the participants can play is restricted according to the number of participants. To elaborate, having two participants means that the host can only choose maps which are designed for two players, and so on.

The multiplayer matches have the same objective for every participant: try to be the last one standing. There does not seem to be any way to select different objectives.

At least the maps may provide different early-match experiences. For example, there are maps which start players far from each other, with plenty of unclaimed territory in between, which in turn means a flurry of late-stage decisions. In contrast, there are maps which start with the players already uncomfortably close to each other.

VISUAL DESIGNS:

That Greed Corp is designed for playing on multiple platforms is apparent almost from the get-go. For a 2010 game that was released on platforms which can support better graphics, Greed Corp would have looked a bit primitive. It does not have lot of polygons in its models, the textures of the models look muddy when viewed up close and the shadowing effects do not look so convincing when shadows fall across tiles of different heights.

There are not a lot of animations for players’ assets. The walkers do have some cute idle animations, but they do not have any other, not even for attacking and defending tiles.

The animations for the harvesters can seem quite impressive, such as when they punch down tiles. However, an observant player might notice a rather abrupt and ugly transition when tiles crash.

When tiles are at their critical layers, their models are already prepped for falling apart, so they look convincing when they do. As for anything else on them though, their models appear to be replaced with other models which have been made specifically for the falling animations.

This replacement of models would not have been an issue, if not for the replacement models looking like they are missing shadows and some textures. They seem to resemble less complete versions of the models which they replaced.

The camera always tries to provide the player with a view of what is happening, though the player can disable this option if he/she prefers to be looking around.

SOUND DESIGNS:

The speakeasy music which is used for the game can be heard from the get-go. It is supposed to match the 1920s-like and steam-punk settings of the game. However, without anything which is immediately associable with speakeasies in the game, e.g. bars, bands and notable relics from the 1920s, the use of this music does not effectively add to the atmosphere.

Rather, it might even sound a bit mocking and whimsical when tiles start to crash around.

Speaking of crashing tiles, the most impressive sounds in the game are those which are associated with crumbling lands and harvesting. Every player’s turn always starts with these noises, since harvesting is always done before the player’s turn starts.

The other sounds are not as impressive or convincing though. For example, there are some attempts to make walkers sound powerful when they go on the attack, but without the animations to accompany this, they sound hollow. In contrast, the carriers and cannons at least have fitting sound effects to go together with their animations.

CONCLUSION:

Greed Corp has a convincing innovation in the form of its emphasis on diminishing territory. However, the rest of its gameplay is not any more sophisticated than a board game which is played to while away an afternoon.