Copycats

In this special GameSpot AU feature, we take an in-depth look at video game piracy in Australia, what the laws are, and how it affects the game industry.

Online piracy has a mighty lure. Armed with a working Internet connection, anyone can download everything from films and TV shows to software and video games. The notion of doing harm, or of participating in an illegal activity, is a nonissue to many. So it should come as no surprise that video game piracy in Australia is rampant. No matter how strong the antipiracy and digital rights management (DRM) measures video game publishers put in place, game piracy continues to grow.

The Interactive Australia IA9 report, released late last year, showed that 17 per cent of gamer adults surveyed admitted to having pirated games in their collections, with nearly 10 per cent of all gamers in Australian homes having illegal copies. Peer-to-peer file sharing now accounts for an estimated 60 per cent of Australian Internet traffic, and console mod-chipping (although now illegal in Australia) continues to flourish as a business. The cost to the video game industry is significant: According to the IA9 report, the cumulative economic impact of video game piracy on the Australian games industry is A$840 million. Australian laws clearly define video game piracy as an illegal infringement of copyright, and the penalties that offenders can incur are far from lenient. So why do people pirate games?

A US study conducted by Microsoft in 2008 showed that half of the young adults surveyed were not familiar with the laws governing the use of online digital content. As a result, Microsoft helped to develop a curriculum for US middle schools to help young people understand how intellectual property rights work. But is education the right answer to curbing video game piracy? Or will publishers feel pressured to impose stricter DRM measures?

In the first part of this feature we analyse the scope of video game piracy in Australia, the laws that govern and protect copyright, the harm piracy contributes to the local video game industry, and local game publisher's perspectives on what can be done to stop piracy. In the second part of the feature we will look at console mod-chipping and how this contributes to video game piracy in Australia. In a follow-up feature, GameSpot AU will look at DRM and the future of antipiracy measures.

Victimless crime?

It seems that very few people have qualms about admitting they pirate movies, songs, and video games. The most likely reason for this is that piracy is a seemingly victimless crime. Video game publishers, movie studios, and record labels are not seen as entities worth pitying; in fact, just the opposite. At one stage or another, we have all been subject to marketing tricks, engorged prices, and plots to make money. Throw in the increasingly high price of video games, CDs, and DVDs and the cost of going to the cinema these days, and piracy suddenly doesn't seem so bad.

According to the IA9 report, of the Australians in the 17 per cent of households with illegal copies of video games, 54 per cent defended their actions by citing high prices charged for new games. Another 36 per cent said they pirate in order to try games before they buy them, and another third said they pirate because they cannot afford all the games they want. One-fifth cited delayed release dates for retail copies of games in Australia compared with other (mainly North American) national markets, and one-fifth said the pirated games in their collection were games that were not released in Australia due to refused classification or because they were distributed in a different market. One-fifth of Australians surveyed said illegal copies are more convenient to obtain than retail copies. Although these insights into gamers' minds would prove otherwise, compiler of the IA9 report, Dr Jeffrey Brand from Bond University in Queensland, said gamers are sensitive to the issue of video game piracy and recognise the importance of supporting the industry. Brand believes Australia's decision to not introduce an R18+ classification for video games is to blame for escalating piracy numbers.

"Australia is the only developed country that doesn't have an R18+ rating, so games which are refused into the country are often downloaded from the Internet and illegal copies are made," Brand said. But with an estimated impact of A$840 million on the Australian game industry, it's worth asking whether Aussie gamers really do get it. Given that Australia is home to largely independent game developers, there is no doubt that piracy is doing substantial harm to the future of our industry.

Tom Crago, president of the Games Development Association of Australia and head of Australian game development studio Tantalus, said gamers don't realise how much piracy harms local studios. "From a developer's perspective, the only financial reward you'll get for the game you've spent two years of your life making is if the game sells well," Crago said. "It would be great if people recognised that when they pirate a game, they're depriving a developer of legitimately earned income. And let me tell you, we're not rock stars; we're small groups of people who work extremely hard to make games that we hope will bring pleasure to those who play them. If consumers aren't prepared to pay to play, then the whole industry collapses."

Crago believes that PC gaming is no longer a viable business for Tantalus. "There's not a great deal we can do in terms of copy protection, as that part of the puzzle tends to be controlled by our publishers, and of course by the platform owners. Larger developers are implementing their own DRM systems. This is very likely the way of the future, assuming the wrinkles can be ironed out."

Representative of the local publishers, the Interactive Entertainment Association of Australia (IEAA) is also doing its best to curb game piracy--the organisation has its own investigators who work closely with local and federal law enforcement agencies to monitor online environments and maintain an antipiracy hotline. "Piracy is not victimless crime," IEAA CEO Ron Curry said. "Whenever someone creates and sells an illegitimate copy of a game, they are stealing money from the many thousands of people involved in development, distribution, marketing, and retailing who have worked tirelessly to create a first-class, local games industry."

The IEAA wants to increase its efforts to stop piracy through education with a soon-to-be-launched antipiracy Web site that focuses on prevention.

"Some of the key factors that lead to video game piracy are the public's lack of understanding that piracy is a breach of copyright--that is, it's a crime," Curry said. "Through a combination of public education on the penalties and impact of piracy, plus tough law enforcement, we hope to reduce this figure." According to Curry, Australia's game piracy levels are increasing through a rising number of gamers and a greater demand for games. "Ease of replication and the rise of Internet file-sharing have had a significant impact on worldwide piracy levels. In Australia, improved technology and growth of Internet file-sharing have been major contributors to the rising levels of game piracy."

Click on the Next Page link to see the rest of the feature!

Laying down the law

Most gamers are aware that piracy is a crime. But ask them what kind of crime, what its scope is in Australia, its penalties and policing, and you'll be met with blank stares all around. According to gamers surveyed for the IA9 report, half of their pirated video game copies came from family and friends, 26 per cent were downloaded from online file-sharing sites, and another 20 per cent came from overseas vendors or market stalls. What most gamers probably didn't realise is that all of these actions carry severe criminal penalties in Australia.

Piracy, or copyright infringement, is the unauthorised reproduction and/or distribution of any material that is covered by copyright law. Under Australian law, piracy is illegal as set out by the Australian Copyright Act of 1968.

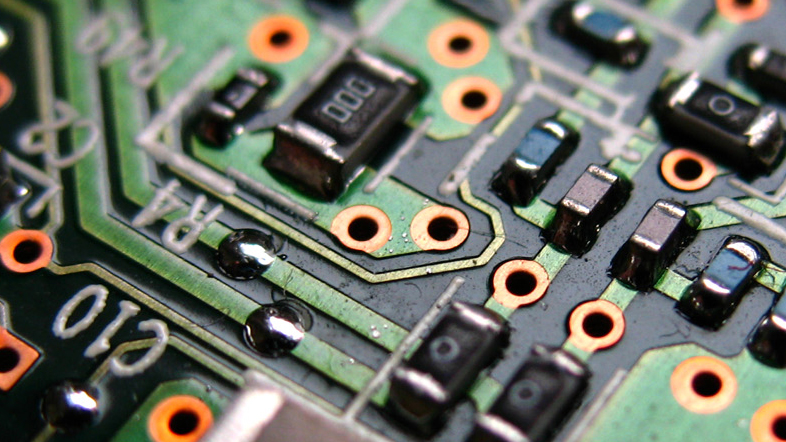

Generally, copyright is infringed if any material, such as text, artistic works, musical works, films, video games, or software, is used without permission in one of the ways exclusively reserved to the copyright owner. The IEAA classifies video game piracy as being when games are illegally copied to a CD or shared on P2P networks; when game consoles are mod-chipped (which involves the soldering of a non-genuine chip on the printed circuit board of the console to circumvent its technological protection measures); and when games are downloaded illegally from the Internet.

Criminal offences for copyright infringement include a tiered offences system, infringement notices, and jail time for offenders involved in commercial dealings and the mass distribution and sale of pirated video games. Penalties for copyright infringement can reach A$93,500 and/or five years imprisonment per offence for individuals. For importation of material that infringes copyright, fines of up to A$71,500 and/or imprisonment for five years apply.

Cases of copyright infringement involving commercial dealings can be taken to the Federal Court of Australia or the Federal Magistrates Court, as well as State and Territory Supreme courts, depending on the offence. When a matter goes to court, courts can order that circumvention devices such as console mod chips, infringing copies, and the devices and equipment used to infringe be destroyed or handed over to the relevant copyright owners.

While not heavily publicised, the Australian Federal Police (AFP) regularly carries out raids to uncover illegal video game piracy operations. In December last year, 2,500 pirated games were found in a Melbourne home, one month after NSW police uncovered thousands of pirated games and films during a raid at a trash and treasure market in Sydney's west.

According to a 2008 report released by the Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC)--Intellectual Property Crime and Enforcement in Australia--one in five households in Australia have, at one time or another, knowingly purchased pirated computer or video goods. Although industry data suggest piracy in Australia is at a low level by world standards, its prevalence led the AIC to believe that there is a high degree of ambivalence amongst the Australian public about the seriousness of piracy.

"Views have occasionally been expressed that IP rights infringement is a 'victimless crime,' being a form of behaviour that is 'technically' illegal but does not violate or threaten the rights of any individuals or companies. Neither the Australian Government nor IP rights owners accept such a view," the AIC report said.

In interviews conducted by the AIC, some interviewees said they were not aware that they were committing a possible criminal act by pirating materials. The AIC hit back with educational and media campaigns that sought to explain why piracy is not a victimless crime, including a joint Crime Stoppers and AFP national crime prevention campaign in 2005 to tackle growing computer and video game piracy; a 2006 education initiative titled "Copyright or Copywrong"; and an ongoing Copyright Advisory Group of Australian Schools and a TAFE awareness program specifically targeted for schoolchildren aged eight to 12.

Taking a different approach to education, the Australian Government aims to tackle rising piracy levels through law enforcement and stronger border-control measures. In 2007, the AFP received an A$12.4 million package to help them target copyright piracy--the funding has resulted in an increase in piracy crime investigations and prosecutions. In November last year, Attorney-General Robert McClelland launched a report on the economic contribution of Australia's copyright industries, where he noted that appropriate enforcement measures to address the growth in piracy was one area that needed to be addressed. "Copyright piracy is a global issue. Material can be uploaded in one country, stored on a server in another country, and downloaded by users in a third country," a spokesperson for the Attorney-General's department said. "We need to ensure that Australia's copyright system remains fair and effective."

Industry headaches

While the government, police, and IEAA continue to work together with the local industry to curb the rising levels of video game piracy in Australia, some publishers have long taken matters into their own hands. For example, Nintendo has begun to significantly invest in the protection of its intellectual property, with DRM now in place on all digital content purchases for the Wii via the WiiShop Channel, including Virtual Console and WiiWare games. Nintendo Australia's managing director Rose Lappin said piracy affects both consumers and publishers.

"From an industry point of view, piracy affects employment, reduces investment, and affects sales," Lappin said. "On the other hand, consumers who receive pirated products may be exposed to faulty goods or inappropriate content."

Nintendo's global approach to curbing video game piracy involves working closely with various authorities in each market. Lappin said education, rather than stricter DRM, is the answer to reducing piracy levels. "Anything Nintendo does, in a technical sense, is always considered from a users' perspective first and foremost," she said. "Education via our industry body, the IEAA, is an important method for providing information to consumers regarding piracy."

Nintendo was the only publisher out of the five contacted by GameSpot AU to speak out; Microsoft, Sony, Rockstar, and THQ chose to leave comment on the issue to the IEAA.

Whether they're trying to protect their intellectual property or protect themselves lest they anger gamers, the silence of both publishers and developers on the sensitive issue of piracy is rarely broken. But rarely does not mean never. In February 2008, former THQ creative director Michael Fitch posted a now notorious response on the Quarter to Three forums blaming piracy for the fall of games developer Iron Lore, whose studio shut down just days before Fitch's post. The studio, in charge of developing Titan Quest and Warhammer 40,000: Dawn of War: Soulstorm for THQ, closed due to financial troubles, prompting Fitch to write the following:

"For a game that doesn't have a Madden-sized advertising budget, word of mouth is your biggest hope. The research I've seen pegs the piracy rate at between 70-85 per cent on PC in the US, 90+ per cent in Europe, and off the charts in Asia. So, if 90 per cent of your audience is stealing your game, even if you got a little bit more, say 10 per cent of that audience to change their ways and pony up, what's the difference in income? Just about double. That's easily the difference between commercial failure and success. That's definitely the difference between doing OK and founding a lasting franchise.

"Titan Quest did OK. We didn't lose money on it. But if even a tiny fraction of the people who pirated the game had actually spent some goddamn money for their 40+ hours of entertainment, things could have been very different today. You can bitch all you want about how piracy is your god-given right, and none of it matters anyway because you can't change how people behave. Some really good people made a seriously good game, and they might still be in business if piracy weren't so rampant on the PC."

Fitch, who is no longer at THQ and is working independently, says that even with the benefit of hindsight, the post he wrote in 2008 still stands true. "My post was really about a variety of issues facing developers who want to make triple-A games on the PC as a platform," Fitch said. "My desire was really to try and get people who are on the consumer side to understand that the challenges PC developers face are much larger and more complex than they may be aware of. The main point that I was trying to make was not that piracy is bad (although it is) or that we need to try to curb it (which we do), but that it's huge. If you look at the numbers, it's astonishing how small of a change it would take to make a major difference in the economics of PC gaming."

Fitch believes publishers and developers are hesitant to talk about piracy because pirates are potential customers, and it is bad business to risk antagonising potential customers. "Clearly, someone who is pirating PC games enjoys PC games, and while the act of piracy may outrage people in the business of making and selling PC games, you don't want to harm your chances that those people may buy your products in the future. It's also a very thorny issue, and a lot of people have near-religious zealotry about their particular take on it."

Personally, Fitch would like to see consumers better educated about the damaging effects of video game piracy. He says if people could take it upon themselves not to accept piracy as normal and justified in their circles, the positive impact this would have on the video game industry would be huge. "At the end of the day, whether they know it or not, they are harming the industry, and I think that a lot of people, if they fully understood the impact of their actions on the people in the trenches, the guys and gals--just like them--who work hard at their jobs every day and want to be successful, some of them would change their behaviors."

Click on the Next Page link to see the rest of the feature!

In Part 1 of Copycats, we looked at the effects of video game piracy on the local publishing and development industry, the laws and penalties regulating it, and asked industry experts for their opinion on how best to curb the rising levels of piracy in Australia. In Part 2, we tackle mod-chipping. Is it legal? How does it contribute to piracy? And finally, what do mod-chippers think about the legitimacy of their businesses? GameSpot Australia’s in-depth look at video game piracy in Australia continues.

Mod-chipping

It’s a common misconception that mod chips are legal in Australia. However, the reality is this: any device, mod chips and Nintendo DS flash cards included, that bypass the protection measures put in place within a console are illegal, following amendments made to the Australian Copyright Act in 2007.

To most gamers, mod-chipping is an all-too familiar aspect of gaming. A mod chip is a simple electronic device installed in consoles that disables the built-in protection measures, circumvents region coding, digital rights management (DRM), and copy protection measures. A mod chip allows gamers to play pirated, unlicensed third-party and/or imported games from other regions, as well as create archival copies. Nintendo DS flash cards also work in the same way as mod chips. Because the DS’ game card slot is encrypted in such a way as to make it only capable of running original games, pirated DS games can be stored on a run from a flash card which is inserted into the GBA slot at the bottom of the console.

Installing mod chips is no easy feat. Most gamers who own mod-chipped consoles have either paid a business for the service, or have employed the skills of a technologically-minded friend (at their own risk). Mod chips are installed inside the console and attached, most often by soldering wires, to the system’s circuit board. Sony’s PlayStation was the first console to be widely mod-chipped, largely due to the fact that copying games was becoming more affordable owing to the ease and price of CD-burning software. With time, mod chips became more sophisticated, allowing gamers to slowly bypass many of the protection measures put in place in all current console systems.

The confusion over the legality of mod chips may have come from a landmark court case between Sony and a Sydney mod-chipper named Eddy Stevens in July 2002. Stevens, who ran a mod-chipping business, was accused by Sony of violating its copyright by selling and installing mod chips for the PlayStation 2 console. Sony lost the case because the judge, Justice Ronald Sackville, ruled that mod-chipping did not violate Australian laws forbidding circumvention of technological protection measures, and found Stevens to be innocent (although Stevens was later charged for selling bootleg PlayStation games).

The Sony case considered whether or not mod-chipping was an infringement of the Copyright Act. Due to certain legal technicalities and the manner in which the PlayStation 2 implemented its protection measures, it was held that mod-chipping the console was not an infringement of the Australian Copyright Act. Sony’s original claim was that the mod chips Stevens sold were capable of circumventing an access code built into the PlayStation 2 consoles, which were designed to stop running unauthorised copies of games. However, Justice Sackville found that Sony’s protection measures on the PlayStation 2 did not conform to the statutory definition of ‘technological protection measure’ and that the mere playing of pirated games did not infringe Sony’s copyright.

Following the case, Sony successfully appealed the Federal Court decision--making mod chips illegal for a short period of time--prompting Stevens to take the case to Australia’s High Court. In 2005, following a four-year legal battle, the High Court ruled in favour of Stevens, finding mod chips to be legal. The court found that mod chips were not responsible for copyright violation because, by the time a mod chip acts upon a copied game, the copyright violation has already taken place i.e., simply because mod chips allow users to play pirated games doesn’t mean mod chips are responsible for the piracy in the first place. At the time of the decision, the court stated: “There is no copyright reason why the purchaser should not be entitled to copy the CD-ROM and modify the console in such a way as to enjoy his or her lawfully acquired property without inhibition.”

When Stevens appeared on ABC Radio National show The Law Report on August 6 2002, it came to light that the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) had intervened in his case, as a friend of the court, to argue that mod chips did not break the law. Sitesh Bojani, the ACCC commissioner responsible for enforcement at the time, had this to say to the ABC regarding why they made the intervention: “Mr Eddy Stevens was a person who was providing a service to modify PlayStation consoles by adding a mod chip… to overcome region coding in PlayStation games. Our concern was that by Sony alleging that this particular service was a breach of the copyright act provisions which make it illegal to make a device or supply a service that is designed to overcome copyright protection measures, Australian consumers in general were going to be severely disadvantaged. We want consumers in Australia to have access to a complete range of computer games; we want them to have access to more competitively priced games; and we’d like them to be able to make use of the legal right they have under the copyright law, to make back-up copies for their own personal use.”

Stevens admitted as much in the same program:

“I mean it’s fair enough, anybody that’s involved in bulk illegal unauthorised copying is obviously doing the wrong thing. But I mean families and stuff that copy amongst them, it’s something that you’re just never going to prevent anyway. Sony’s been making plenty of profits and I would say as far as families go, they should just live with it. They say that [mod] chipping is actually aiding people to play illegal copies, but the problem with that is that the way the protection is with the discs--if you’re a family man with five-year-old kids or something and you go and spend $90 on a game, you don’t want to give that to the kids, because there’s every chance that it’s going to get destroyed,” he said.

“So you make a copy and you want to play the copy. But the way the machine is, and the actual copy protection on the discs, you can’t do that, because it’s just not possible the way the whole thing is designed. So legally, you should be able to use a backup and I think that’s probably part of the reason why the actual court ruled that it wasn’t illegal to put chips in. The only difference between the legal and illegal is people’s attitude to it, basically.”

The Sony vs. Stevens case was the first of its kind in Australia in that it was the first to look at technological protection measures. However, amendments made to the Australian Copyright Act in 2007 due to the US Free Trade Agreement have turned all this around. Mod chips, their sale and distribution, are now illegal.

Ron Curry, president of the Interactive Entertainment Association of Australia, sums it up. “Mod-chipping is not legal. Amendments made to the Australian Copyright Act repealed the provisions upon which the Sony vs. Stevens mod-chipping case was decided in the High Court. The new provisions now also cover ‘access control technological protection measures’, which are worded to include mod chips. Amendments to the Act allow an owner of copyright to take action against a person who provides a circumvention service to get around technological protection measures. In addition, new criminal offences have been inserted in relation to offering circumvention devices to the public.”

The legality of mod-chipping

Over time, publishers have worked tirelessly to find a way to equip their consoles with anti-mod-chip measures. Microsoft came up with a way to ban mod-chipped Xbox 360 consoles from accessing Xbox Live, while Sony, learning from its past mistakes with the PlayStation and PlayStation 2, built the PlayStation 3 in such a way that it is practically impossible to mod chip. In addition, the PS3’s features actually make it more attractive to those who would normally want to mod chip a console: it is region free, meaning gamers aren’t restricted to playing region-locked games, and users can install Linux and their own hard drives on the console. It also uses Blu-ray discs, which are costly.

While these measures seem to be working, there are no signs that video game piracy is slowing down. The purpose of a mod chip, as it is understood not only by gamers but also by the law, is to circumvent copy protection mechanisms; in short, mod chips make it possible to play illegally copied, or pirated, games. The circumvention of copy protection mechanism is illegal in many countries, including Australia. For example, under the United States’ Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), introduced in 1998, it is illegal to produce and distribute any device, technology or service intended to circumvent DRM, regardless whether there is an actual infringement of copyright going on. Similarly, the European Union’s Copyright Directive (EUCD), passed in 2001, outlines the same stance on devices that are designed to infringe copyright. Because of the varying uses of mod chips, and their relatively wide implementation, these acts do not specifically refer to them; the legality of their use is judged on a case by case basis in court, and depends on each country, the ruling judge and his or her interpretation of the law, and the facts as they apply to each individual case.

Click on the Next Page link to see the rest of the feature!

However, Australia’s legal stance on mod chips is much clearer. In general, the provision of mod-chipping services and devices is illegal in Australia, and exposes the provider to both civil and criminal penalties. The current Australian Copyright Act, which previously made no mention of circumvention devices such as mod chips, was amended in early 2007 as part of the US Free Trade Agreement. It now stipulates that it is prohibited to:

a) Circumvent access control technological protection measures (ACTPM) (section 116AN);

b) Manufacture, distribute or offer a circumvention device (section 116AO); and

c) Provide circumvention services to the public (section 116AP).

Under current Australian law, an access control technological protection measure (ACTPM) is any product or technology that is used by or on behalf of the owner of the copyright to control access to the copyrighted works. In the case of video games, these measures control access to the copyright works (i.e., the games) on behalf of the copyright owner (i.e., the game publishers), and include DRM and any other measures in place to prevent piracy or the hacking of a console.

Circumvention devices are defined as devices or products, including computer programs, that have the purpose of circumventing (i.e. getting around) ACTPMs, or are primarily designed to facilitate circumvention. A mod chip is a circumvention device because one of its purposes and abilities is to get around the protection measures in consoles. Finally, a circumvention service is any service provided by a person to facilitate circumvention. Any business that sells or installs mod chips is a circumvention service.

Given the current law, it is therefore illegal in Australia to use a mod chip to play pirated games, to manufacture, sell or install mod chips. The penalties for doing any of these prohibited acts are grave--the copyright owner is entitled to bring a civil action against any person or persons found guilty. A person may also be guilty of criminal offences for engaging in these acts.

Down to business

The illegality of mod chips and mod-chipping in Australia will no doubt come as a surprise to many. In fact, simply Googling the words ‘mod chip’ will produce a long list of mod-chipping businesses in Australia who are all presumably operating with a legal business licence. However, what they’re doing is technically illegal.

GameSpot AU contacted two mod-chipping services to gauge their views on their business ethic, clientele and their thoughts on the link between mod chips and piracy. For their privacy, we have refrained from using their business names and the real names of the individuals we interviewed.

Mod chipper A has been running his mod-chipping business based in Melbourne, where he says he began the service because there were no suppliers that were efficient, honest, and had the ‘balls’ to stock new products. One year on, A says his business is the biggest supplier of Wii and DS mod chips in Australia, with business growing daily. “Consoles are computers,” A said. “They are powerful devices that cannot be used properly until they are ‘unlocked’. For example, the Wii is totally region locked. Mod-chipping the Wii allows users to play almost all games from other regions, as well as use their consoles to play DVDs.”

Mod chipper A says he sells mod chips to four types of customers: people that are interested in playing ‘homebrew’ games, people that are interested in playing backups of games they legally own, people who want to play region-locked games and finally, people who are interested in piracy. “If you think about mod chips the same way as DVD burners for the PC, then you could argue that 90 per cent of people use the latter to copy games, movies and MP3s,” A said. “However, this does not make DVD burners illegal.”

Mod chipper A says that his customers are more likely to only buy consoles they can modify. “The guys that give mod-chipping a bad name are those who sell pirated games in markets,” A said. “Publishers like Nintendo, Microsoft and Sony should concentrate their efforts into shutting these people down, rather then going after the manufacturers of [mod chips].”

Another mod chipper, B, has been running his business in Brisbane, where he says in the past two years business has been slowing down due to the current generation of consoles being limited to the ways that you can modify them. “The main reason people get their consoles modified is because the majority of them are families who have children,” B said. “With games being more expensive in Australia, parents would prefer to have the option to backup their original games and put them away for safekeeping and let the kids play the backup copies--that way when they do get damaged they have the original to make another backup copy. That way the parents are getting more value for money from their purchases plus peace of mind knowing their original games are not getting damaged from continuous play.”

Mod chipper B is aware that some of his customers mod chip their consoles to play pirated games, but he said this does not outweigh the number of customers who mod chip their console for legitimate reasons, such as people who have purchased games from overseas, people who purchase games from eBay that do not work on their console, and amateur game designers and programmers who need a modified console to test their games on. “In my opinion, one can say that mod-chipping benefits the video game industry in Australia because it gives consumers peace of mind knowing that they can backup their original games and not have them damaged. That way, consumers are more likely to purchase more games, knowing that they are going to get the maximum life from their investment.”

At the time of the interview, both A and B admitted that if mod-chipping were illegal in Australia, their businesses would be forced to shut down.

Piracy is a complicated issue. While gamers feel that the rising cost of video games in Australia entitles them to copy games illegally, the harm done to the local video game industry is pushing developers and publishers into a corner. Pirating video games and mod-chipping consoles are now both illegal activities under Australian law, and can incur serious penalties for individuals, including jail time. The game industry believes better education on the harm of video game piracy is the answer to curbing the problem; the Australian Government believes stronger law enforcement is necessary. Whatever measures are planned for the future, one thing is certain: piracy has the potential to destroy the Australian video game industry. If gamers keep this in mind, it might just be enough to stop it from happening.

Got a news tip or want to contact us directly? Email news@gamespot.com

Join the conversation