Shock and Awe

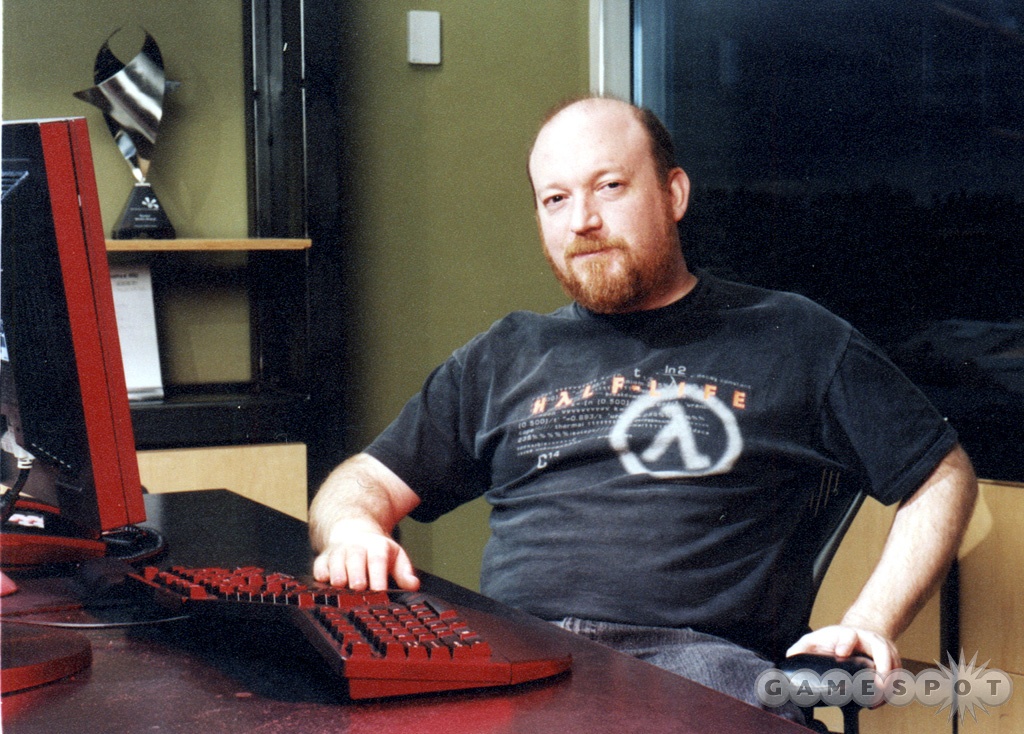

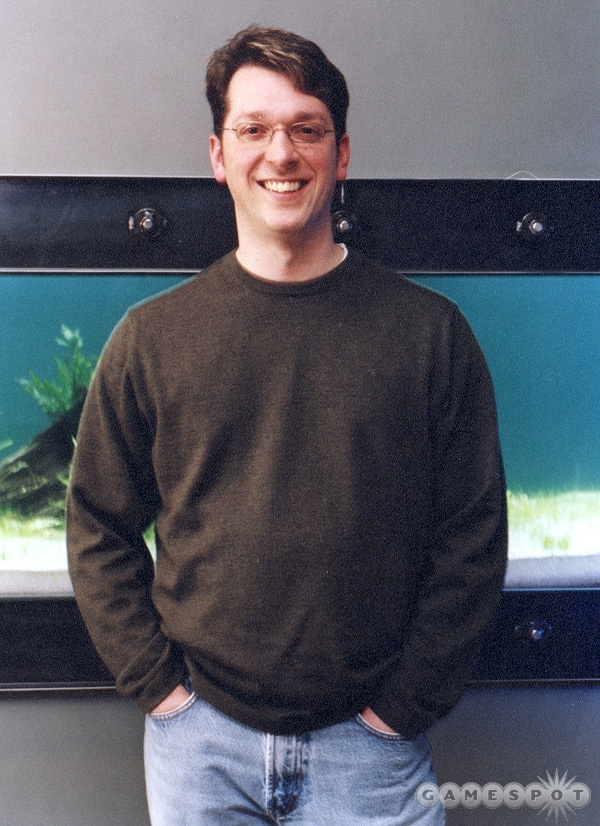

Gabe Newell is about to make a promise. It's 11am on an overcast morning in Bellevue, Washington, and Newell, the impresario behind Valve, lumbers into the company's starkly decorated 10th-floor conference room. He pulls out an Aeron chair, plops himself down, and runs his stubby hands through his reddish-brown hair.

"OK," he says, taking a deep breath. "During any project there comes a time to draw a line in the sand and put a stick in the ground and say, 'This is it. We're ready,'" he says. "That moment, I'm happy to say, is right now. We finally know when this game is going to be done."

The game he's referring to is Half-Life 2, the sequel to Half-Life, one of the best-selling PC first-person shooters of all time. For years gamers have impatiently waited for definitive news on the sequel. Now Gabe is ready to announce a release date. As Newell talks about the game's imminent completion he speaks with such conviction that you half expect him to give you the exact minute and second the game will be released. He sounds that sure of himself.

Before he divulges the date, however, he pauses. He pulls off his smudged glasses and gently runs an index finger over his right eyelid. "Sorry, I was up really late last night," he explains. Understandable, you think to yourself--it's never easy pulling all-nighters to finish a game.

Unfortunately, Newell's fatigue is the result of something else entirely. "I was up until 3:30am last night watching the first night of bombing in Iraq on CNN," he explains.

Uh-oh.

Today is March 21, 2003--the start of the second war in Iraq, which is a fitting parallel to the battle Newell is about to start with the announcement of Half-Life 2 and its release date. Like the second American offensive in Iraq, Newell's battle will begin today with a shock-and-awe campaign of spectacular visual firepower--the first demo of the game. Unfortunately, the parallels don't stop there. From the perspective of many fans, Newell's battle to release Half-Life 2 will also end up being a campaign filled with misinformation. And at times there will seem to be no exit strategy for Newell, no clear sense of when victory--the release of the game--will be achieved.

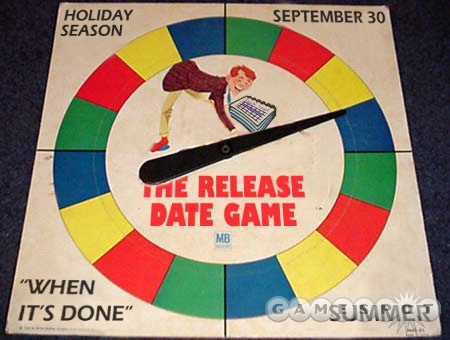

But none of that is evident to Gabe today. No, today is a day of great resolve--a carefully calculated announcement of Half-Life 2 and a public declaration that the game is about to enter the final stretch of development. "We didn't want to do the whole 'when it's done' thing," Newell explains in his preamble. "The reason we are announcing the game today is because we now know when it will be done."

OK, so when will it be done?

"We're going to launch the product at E3 and we're going to ship it on September 30, 2003," Newell empathically states. Knowing what you know now, you want to coach Newell to not be so sure of himself. He could say "September" and no one would complain. Even "fall" or "when it's done" would probably fly. But no, that's far too imprecise for Gabe. Today he wants to make a promise to the fans, to open the eyes of expectation. Half-Life 2 will be coming on September 30, 2003. Not "hopefully" or "maybe" September 30. It will be coming September 30.

"The reason we are announcing [Half-Life 2] today is because we now know when it will be done."- Gabe Newell, March 2003

Of course, Half-Life 2 didn't arrive on September 30. In fact, it wasn't anywhere close to being done on that date. Today Newell admits the statements he made in March 2003 have haunted him every day for the past 18 months. He was embarrassed. He felt paralyzed. He didn't know how or when to explain what really happened.

Now he's ready to come clean.

Club Zero

It's September 30, 2004, and Gabe Newell is looking to the heavens. "OK, what now?" he asks the gods above, wondering aloud how the forces of nature will next conspire against Valve. You imagine the thoughts that must be running through his head. Maybe a meteor will hit the building. Lighting could strike him down. A massive computer virus might infect the network. Given the roller-coaster ride that Valve has been on for the past 18 months, all three of these things seem more likely than what Newell is about to say.

"We were right about the date, just not the year," he says with a smile. Yeah, sure, Gabe. You really expect us to believe that Half-Life 2 is nearly done? Newell just grins wider, turns around and slowly points at an object hanging from the ceiling. Fashioned after the scanner robot in Half-Life 2, a papier-mâché piñata hangs in the air, awaiting its fate. "We just hung it up this morning," Newell boasts. Just as he eviscerated a headcrab piñata the day Half-Life was finished, Newell will whack the scanner piñata as soon as Half-Life 2 is sent off to duplication. OK, you think to yourself, maybe Valve really is within hours of finishing the five-year, $40 million odyssey that is Half-Life 2's development. Either that or Newell is sure good at building up the drama.

Further confirmation of Half-Life 2's imminent release comes at the "4 o'clock" meeting where Newell assembles the team for a status update. There have been more than 2,000 of these meetings since the game first began development. This may be one of the last.

Today's meeting is all about reviewing the members of "Club Zero," a list that appears on a whiteboard. Programmers join the club as soon as all their bugs are fixed. Many of them are already in the club, but a few have yet to join. (You can also be dismissed from the club if someone finds a bug in your level). "We cheer when people join Club Zero and boo when you get moved out of it," explains John Guthrie, the lanky young designer who joined Valve eight years ago, when he was 23. Given the rate that employees are joining Club Zero, Newell thinks the game may be done today or tomorrow. All the bugs are almost gone. More than five years in a pressure-cooker environment might finally be coming to a close.

But will the game ship to consumers anytime soon? That's the question that's been nagging Newell all day. He says the game's publisher, Vivendi Universal Games, is "sort of refusing to tell us anything" about the game's release date. There's little wonder why: Valve and Vivendi have been embroiled in a bitter lawsuit for two years related to the sale and distribution of Valve's games. Newell doesn't know if Vivendi will ship the game when it's finished or hold it hostage for up to six months. It's clear there is no love lost between Valve and its publisher.

The lawsuit against VU Games caps off a development project that, at times, has seemed almost cursed with lawsuits, crimes, delays, and general uncertainty. "It's been hard enough to build the game technically, hard enough to build it artistically, and hard enough to do the gameplay," Newell admits as he slowly walks the halls of Valve after the meeting. "But to have some of these other challenges on top has been a bit too much." In this case, the crushing pressure to build a worthy follow-up to Half-Life--which won more than 50 game-of-the-year awards--was just the first of Valve's worries.

Then again, maybe all the drama was to be expected. Half-Life 2 isn't just a game. No, saying that would be like saying the Atlantic Ocean is just a body of water. Newell sees Half-Life 2 as an engine, a platform, or at best a whole industry unto itself. Going forward there will be engine licenses, hundreds of user modifications (mods), episodic content, sequels, add-ons, and expansions. And Steam, Valve's digital distribution network, may forever change the way consumers buy games. Newell once told The Puget Sound Journal that he hopes Half-Life 2 will sell more than 15 million copies in three years. That would translate into more than $700 million in revenue, making Half-Life 2 a bigger hit than Grand Theft Auto: Vice City and Halo combined.

Half-Life 2 may end up being all those things--a huge success, an agent of change, and a sign of where games are going next. But behind the flashy graphics and the visceral first-person shooter gameplay is the story of what it took to bring this ambitious game to life. For the 84-person team at Valve, the five-year odyssey of creating Half-Life 2 was a strenuous--and sometimes painful--voyage that tested everyone's loyalty to the project.

Now, for the first time, the team at Valve opens up about its journey in stunning detail. No question was off limits: From the missed release date to the code theft to the lawsuit with Vivendi, you'll hear directly from Valve about what really happened. And you'll find out about other struggles that have never before been revealed to the public. Ultimately, this is a story about sacrifice. A story about how 84 passionate gamers gave up nearly everything over five years to create what Newell believes is the best first-person shooter ever created.

This is the story behind the making of Half-Life 2.

What's It Going to Take?

"This time the stakes are different."

It was with those six words that Gabe Newell launched the development of Half-Life 2 in June 1999. Yes, you read that right--1999, only six months after the original Half-Life shipped. For Valve there was never a question about whether there would be a sequel to Half-Life. The question was how the company could top--or even match--what was being heralded as one of the best PC titles of all time.

It was, to be sure, a long way from where Valve started back in 1996. "Last time the fact that a bunch of ex-Microsoft operating-systems guys could get together and ship a game--any game--was a cool story," Newell told the team in reference to Half-Life. "This time we have to follow up the best PC game of all time and do it in a way that doesn't completely burn out the entire staff."

Valve certainly could have created a quick and dirty sequel to capitalize on Half-Life's success. Newell, however, made it clear that wasn't an option. No, Half-Life 2 had to be something much more ambitious. It had to redefine the genre. To innovate where other games hadn't. To be a game that gave fans a totally new first-person shooter experience. "What's the number one thing that drives us?" Newell says. "Well, I just hate the idea that our games might waste people's time. Why spend four years of your life building something that isn't innovative and is basically pointless?"

"Why spend four years of your life building something that isn’t innovative and is basically pointless?" Gabe Newell

Making a revolutionary sequel wouldn't be easy. So, to increase the chances of success, Newell told the team that, at least initially, they had a virtually unlimited budget and absolutely no time pressure. "There's going to be no producer making bad decisions about what has to happen on this project," Newell told the team. All the money Valve made on the original Half-Life would be rolled into the sequel. And since Newell was well-off from his days at Microsoft, he was willing to personally endow the development if necessary. "The only pressure we have is to build a worthy sequel to Half-Life," he told the team.

The experimentation and brainstorming began in the summer of 1999. Ideas were discussed for weeks and thrown up on the whiteboard. What if the game included voice recognition so you could actually talk to characters? What if Half-Life 2 was a buddy story where you and Barney--the AI security guard from the original--worked as a team for the entire game?

Eventually the team crystallized their thoughts around the key concept of making both the characters and the world in Half-Life 2 more believable and interactive. The original Half-Life was heralded for many things, but players particularly appreciated the characters and storyline. "It sounds really goofy, but what we wanted to do was broaden the emotional palette in games," Newell says. "We wanted to try and create characters that mattered and have the player feel a strong attachment to them."

Valve also wanted to bring the world to life. Interactive environments have long been synonymous with first-person shooters, but in the past the interactivity has been limited to flushing a toilet or getting a can of Coke out of an in-game vending machine. Valve wondered if it could create a world that was even more interactive. "The inherent promise of games is that you are an agent in this world and you can affect things," Newell says. So an idea went up on the whiteboard: What if Half-Life 2 used physics, AI, and game design to push the boundaries of interactivity? The team imagined scenarios like letting a player pick up a radiator in an apartment building to use as a shield against an enemy.

By the end of the summer it became clear that Valve would need a new game engine to pull off its ambitious goals. (Valve licensed id Software's Quake engine for the original Half-Life). While Valve looked at licensing an engine for the sequel--such as id's Quake III engine--the team concluded that no outside technology was a good match for Valve's ambitious plans. "Id's stuff is always cutting-edge, but this time we wanted to cut some different edges," says Valve cofounder Mike Harrington. Valve, it seemed, would have to build its own engine from scratch. So while Half-Life 2 may have started production in mid-1999, creating a new engine meant that the game would take at least three years to complete.

A Bittersweet Goodbye

By all accounts Half-Life 2 was going to be a hugely ambitious project. Most of the team members from the original game were more than happy to reenlist for the sequel. But one key member started having second thoughts. He happened to be the cofounder of the company.

Mike Harrington was one of the Gabe's old buddies from Microsoft. They worked together for years and left Microsoft in 1996 to form Valve, a true 50-50 partnership between two best friends who balanced each other out. Gabe was the ambitious dreamer, and Mike was the practical realist who "liked to ship product," as he often told friends. Newell became the public face of Valve, but Harrington was the company's secret weapon--he was responsible for much of the programming on the original Half-Life. As plans for Half-Life 2 began to solidify, Harrington had to decide if he wanted to devote at least another three years to a new Half-Life game. "Part of the problem for Mike was that we succeeded so much out of the gate with Half-Life," Newell says. "I think he said to himself, 'Do I really want to put my ego and self-worth at risk again?'"

Harrington decided the answer was no, in part because he had long planned to take an extended vacation with his wife, Monica, another former Microsoft executive who worked as Valve's first director of marketing. Mike and Monica had dreams of building a boat and exploring the world. They had enough money from their days at Microsoft--the question was whether Mike had the time. Harrington spent weeks contemplating what to do. Eventually he realized that making one Half-Life was enough. "At Microsoft you always wonder, 'Is it me being successful or is it Microsoft?'' he says. "But with Half-Life I knew Gabe and I had built that product and company from scratch." So Harrington decided to leave on a high note. On January 15, 2000, he checked in his last piece of code and then dissolved his partnership with Newell. "It was really sad that first day after I left Valve," he recalls. "Something that was so intense, so powerful, and so engaging was completely gone from my life."

To the outside world it would seem like nothing had changed at Valve. But to Newell, Harrington's departure was much more significant. It made him feel isolated and alone. "It was really hard," Newell admits. "Mike was the one person who I could talk to more than anyone else about things that worried me." Still, Newell wasn't about to retire and shut down Valve. "I'd go insane if you put me on a boat or if I tried to learn how to golf," he says. (Harrington, on the other hand, did just that: He and Monica built their own 77-foot boat, the MV Meander, which they now sail around the world).

Harrington's departure was tough on Newell, but he couldn't dwell on it for long. Valve needed to aggressively push forward with Half-Life 2 and begin experimenting with new technology.

Wild Experimentation

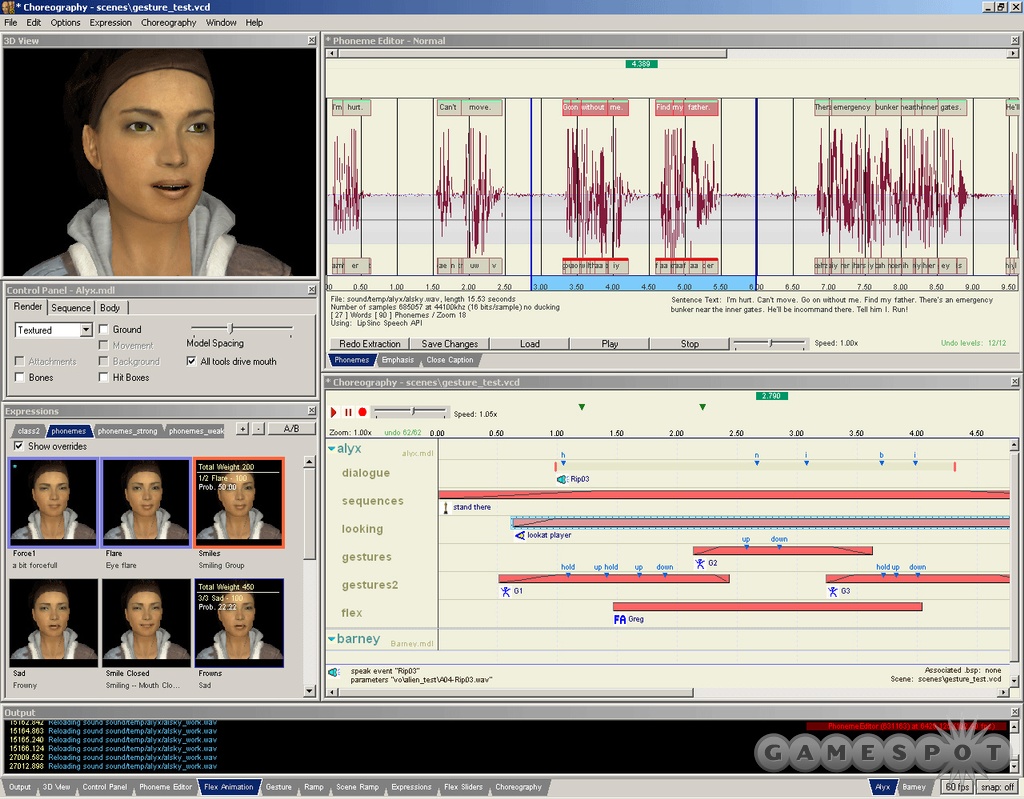

"As she lifts her arms up her breasts rise and flatten," says Valve's Ken Birdwell. He's showing off one of the character models for Alyx Vance, the female lead in Half-Life 2. Birdwell, who once wrote software to create custom shoe insoles, was the man tasked with making more-believable characters for Half-Life 2--characters who could express emotions through their faces and have full musculatures, as evidenced by the breast demonstration.

Why did Valve place such an importance on creating more-believable in-game characters? Birdwell says the decision was a result of the player reaction to the primitive but engaging characters in the first Half-Life. "We didn't spend a lot of time on them in the first game," he says. "But people anthropomorphized them a great deal. People genuinely felt bad when Barney was killed in the original." For the sequel Newell wanted the team to take those characters to the next level by adding believable facial animation and body movement. "I told Ken I wanted players to see the characters as real people and stop thinking of them as automatons or robots," Newell says.

That was an ambitious goal, considering that Hollywood animation houses had yet to crack the problem of creating realistic CG humans. Nevertheless, Birdwell began researching how he might create lifelike in-game characters. He spent some time working with Dr. Ken Perlin, a professor at NYU who is one of the leaders in the computer-graphics field. Perlin's Web site at NYU includes a demonstration of his computerized characters. Birdwell also came across the work of Dr. Paul Ekman, a psychologist who had trained police officers how to detect liars by studying facial expressions. Back in the '70s, Ekman wrote an influential book that laid out a set of rules about how facial muscles work together to create expressions like sadness, glee, anger, and puzzlement. (Eckman's rules were also used to help diagnose mental illness). Birdwell thought that by setting those rules inside the computer he could create in-game characters who would never make unnatural expressions.

Jay Stelly, meanwhile, focused on integrating physics into Valve's new Source engine. For years game companies had attempted to use physics to make more-believable worlds, often to disastrous results. (Remember Trespasser?) Valve was determined to do physics the right way. "We wanted integrated physics that mattered in gameplay," Newell says. As Stelly puts it, "We wanted to do physics so they would reinforce your presence in the world. If we did it right, players would be able to impact their surroundings and take the game beyond the constraints of scripted action." The idea was to take a regular game level and turn it into a playground of sorts where players could manipulate objects and solve puzzles in multiple ways.

While the core technologists worked on the engine, the rest of the team began thinking about the gameplay and story. Still, they kept an eager eye on the new technology. "We wanted to be like Hitchcock and use our new technology in deliberate ways that could have a huge impact on gameplay," says Marc Laidlaw, Valve's resident writer. "I always think of how Hitchcock used the zoom lens for the first time in Vertigo. It was a very specific effect and afterward everyone did the zoom in and out just like him."

The Hemoglobin

As research and development continued, the rest of the team fleshed out the plot and gameplay. Although Newell was expecting the new game engine to dazzle audiences, he wanted to avoid building a sequel that was all about whiz-bang technology. "Our games aren't about throwing you in a room with a gun and a bunch of enemies and saying, 'Go have a game experience,'" he says. "Look at the tram ride in Half-Life--it had an almost operatic quality."

"Our games aren't about throwing you in a room with a gun and a bunch of enemies and saying, 'Go have a game experience.'"Gabe Newell

Half-Life's memorable storytelling can be traced to Laidlaw. A former legal secretary and novelist, Laidlaw worked with the team to create the game's overall narrative structure--he cross-pollinated ideas among the technologists, artists, and designers. So it's hardly surprising he's sometimes referred to as the "hemoglobin" of the team. While it would be easy describe Laidlaw as the game's writer, his role is deeper than that. "I'm a story guy but what I'm doing is in service to the gameplay," he says. "I'd be perfectly happy to work on a game that doesn't have a line of dialogue or text in it."

Laidlaw says the Half-Life 2 team never wanted to stray far from the plot and storytelling devices that worked in Half-Life. "We still wanted to do a game about the journey of Gordon Freeman," he says, referring to the MIT-educated scientist who starred in the original game. "It's a story about a guy who doesn't speak and who finds out about himself only through what others tell him. The great thing about Half-Life is that Gordon walks around with everyone assuming he knows what to do. In fact, the player doesn't have a clue."

Gordon would be back for the sequel, as would the G-Man, the mysterious briefcase-carrying operative who now employs Gordon. But Black Mesa, the New Mexico research facility featured in the original, would not make a return. "The problem was that because the original game was set only in Black Mesa, we didn't have to think what was beyond its walls," Laidlaw says. For Half-Life 2, Valve wanted to create a brand-new environment that could support more-varied gameplay. "We just started coming up with a random list of environments that would be a visual challenge and fun to build," Laidlaw says. "We wanted to go from a unified lab to a much more epic and global feel."

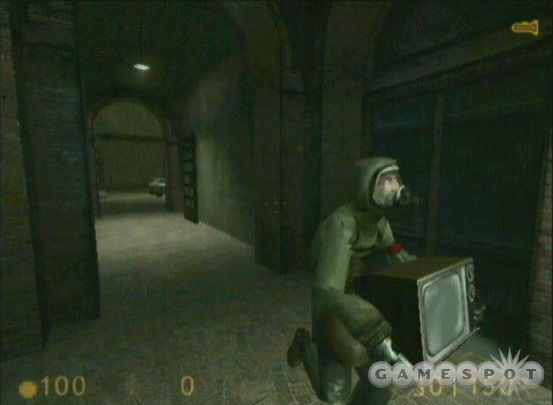

At first the team considered designing a game where Gordon would teleport to various planets around the galaxy and combat the Xen aliens from the first game. But Laidlaw says the team ultimately rejected that idea because it would be hard to create continuity between levels. Then Viktor Antonov--Valve's Bulgarian-born art director--suggested that the team think of setting the game in the suburban and outlying areas around an Eastern European-style city. The team liked the idea. Soon "City 17" was born.

In Laidlaw's first pass at the script, players would start the game by boarding the Borealis, an icebreaker bound for City 17. Once players arrived, they would discover the Combine, a new group of aliens trying to take over Earth, and Dr. Breen, an ominous Big Brother-like figure who appears on television monitors throughout the city. Half-Life 2, like the original, would be a voyage of discovery for the player. Valve would purposely not tell players how long it had been since the original game or what Gordon was doing in City 17.

Once Laidlaw nailed down the plot points, he then focused on fleshing out specific characters. Birdwell's impressive in-game character models meant that there would be huge potential to create drama using richly animated characters. (Like the original, Half-Life 2 wouldn't include any cutscenes or have Gordon speak). Laidlaw, working in collaboration with designer Bill Van Buren, honed in on the idea of building familial relationships between characters such as Eli Vance, a scientist, and Alyx, his daughter. "Characters in games don't really have families, but it's this basic dramatic unit everyone understands," Laidlaw says. "I know, I know--this isn't the stuff you'd expect to see in a game derived from Quake and Doom," he admits with a chuckle.

Zombie Basketball

By mid-2001, Valve had been working on Half-Life 2 for almost two years in complete secrecy. And what did it have to show for all its hard work? Not much. There was a rough script, a bunch of concept art, and tons of experimentation being performed with the technology. Now it was time for the team to try to blend all that technology together--the characters, the physics, and the new Source engine.

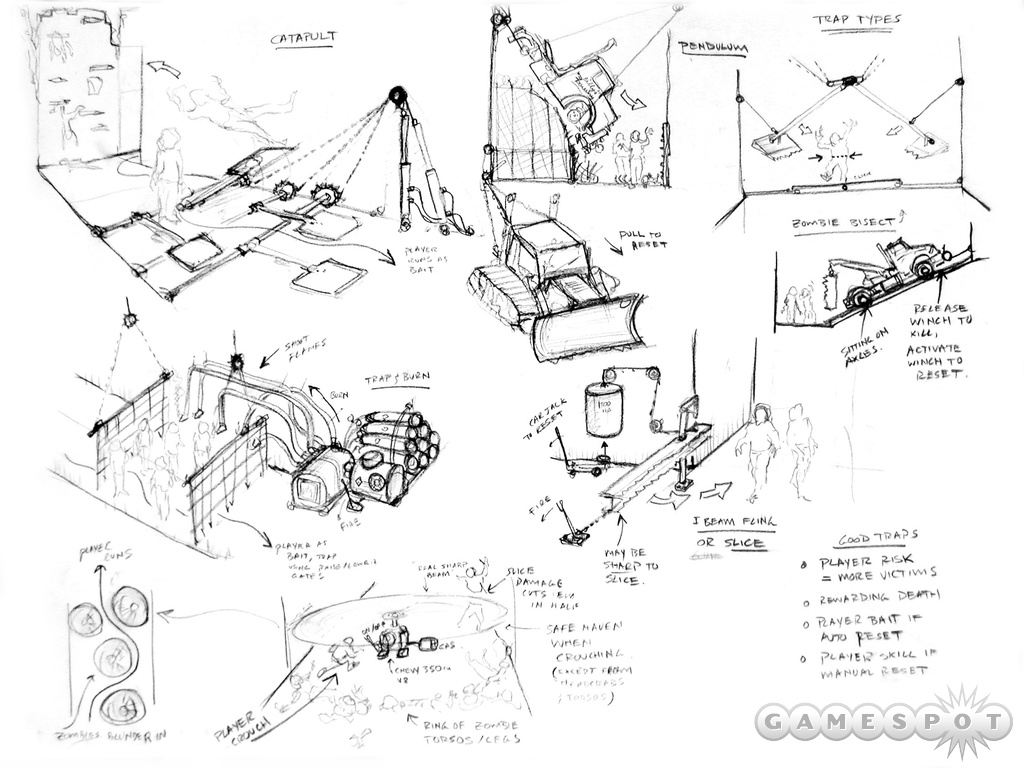

The first big breakthrough came when the physics started working inside the game environment. All of a sudden, static game levels became virtual playgrounds where the team could create objects with mass and have forces act on them. Some of the designers even developed a minigame called Zombie Basketball, where they used a physics-manipulator gun to throw zombies through hoops and get them to land in trash bins. "We got the physics working and started saying, 'Wow, we can do anything in this game!'" Laidlaw remembers. "But then we came to the painful realization about what that was going to mean for the design. It was going to be a nightmare to give players so much freedom."

Still, designers like Guthrie thought that allowing players to manipulate objects would help the designers invent new gameplay paradigms. "I imagined throwing saw blades to cut enemies in half, tossing a paint can against a wall and seeing it splatter," he says. "It was going to add another whole layer to the gameplay. It was going to give us what we needed to differentiate this game from Half-Life."

Another point of differentiation was Birdwell's character technology. Rumors began swirling around the industry that the characters looked as good as those in the Final Fantasy movie, The Spirits Within. Valve recruited Bill Fletcher, a Disney animator, to bring the characters to life. Microsoft chairman Bill Gates, who used to play poker at Newell's apartment, even requested an in-person demo.

Suddenly there seemed to be a lot of positive momentum on the project. So Valve decided to try something ambitious during the summer of 2001: The designers started working on a test sequence that would highlight all the new technology. The concept was to simulate a street war between rioting citizens and the Metrocops sent to contain them. Such a sequence would test the engine's ability to create a vast, believable world and lifelike characters. There would be APCs and tanks rolling down the streets. Citizens would throw Molotov cocktails at the vehicles, which would then gloriously explode, thanks to the physics engine. Other characters would start looting stores and yell, "Get your free TVs!" There was even a hand-to-hand fighting system so the Metrocops and citizens could get into fistfights.

No one actually thought the level would make it into the final game. "It was really just an early attempt at getting something--anything--in the game that used non-player characters and physics," Guthrie remembers. Still, the street-war sequence showed tremendous promise. So much promise that, after seeing the sequence, Newell asked the team to prepare a "proof of concept" reel for the actual game. The reel would contain about a dozen different snippets of gameplay. If it looked good, Half-Life 2 would be given the green light for full-scale production. In late 2001, the team started work on the reel, hoping to finish it in early 2002 and then unveil the game at E3 2002.

But soon the team would discover the challenges of working with new and unstable technology. Half-Life 2 was about to hit its first major speed bump. And the geniuses at Valve were about to get a frightening reality check.

The E3 That Never Was

Normally, Gabe Newell prides himself on being an integral part of the design team at Valve. On Half-Life 2, he even came up with the idea of making Dr. Breen, the main antagonist, the same character as the administrator from Black Mesa in Half-Life. But in early 2002 Newell let the rest of the team take the lead on the development of the game. He wanted to make sure he maintained an unbiased perspective on the proof-of-concept reel. That way, he would be able to accurately judge how the press and fans would respond to their first look at the game. So for months he turned a blind eye to the game's development. That didn't mean, however, that Newell was about to head off on vacation.

Instead, he began working on other projects, like Steam, Valve's ambitious online distribution platform. Newell unveiled the platform at the Game Developers Conference in March 2002. Onstage, Newell positioned himself as a new-age Robin Hood who wanted to take from the greedy publishers what independent game developers deserved: a larger piece of the revenue pie. Newell told the crowd that, under the current system, most developers make only about $7 for each game they sell. But an online distribution platform like Steam--which cuts out the middleman and delivers a game directly to the consumer's desktop--could net developers more than $30 per copy. Newell announced that, while Valve still planned to ship its future games to retail, it would also start releasing games over Steam.

Back at Valve, the team was putting the finishing touches on the noninteractive proof-of-concept reel. As soon as Newell returned from the GDC, he was ready to see what the team had accomplished. Everyone knew the reel wasn't perfect, but they had made tremendous strides in a short amount of time. The characters, physics, and game engine all seemed to be working together for the first time. The team put on their game faces and summoned Newell into the conference room.

As the reel started, Newell carefully watched the screen. The employees nervously watched Newell's face for any reaction--even a faint smile. The first few segments showed how the physics would work inside the gameworld. Other segments showed off environments, like the Borealis. But the linchpin of the demo was a nearly 20-minute scene that took place in the science lab of Dr. Kleiner--the bald-pated scientist who appeared with Gordon and Alyx in the demonstration. The dialogue-heavy sequence was an attempt to show the strides Valve had made with in-game storytelling and emotion.

Then the reel faded to black. That was it. Everyone eagerly awaited Newell's reaction.

Oh My God

The lights came up and Newell turned to the team to deliver his verdict. "You guys did amazing work," he said. But the way he complimented the team made everyone think there was a big "but" coming. They were right. "We could take this to E3," Newell told the team. "But you want this to be the thing the fans want it to be--something that is going to blow them away." The implication was that the demo wasn't quite good enough. The character technology was visually impressive but the dramatic scenes were too long and boring. The physics gameplay seemed interesting, but there weren't any moments that really sold how the physics would take first-person shooters to the next level. Newell finished his review by delivering the bad news: "Guys, unfortunately we are just not there yet." The decision had been made. Half-Life 2 would not appear at E3 2002.

"Guys were walking around the office saying, 'Oh my God, what if we actually f*** this up?'" Gabe Newell on the aftermath of the failed proof of concept

Suddenly, the momentum on the project disappeared. After nearly three years of work, the employees began wondering if they were on the right track. No one was confident about the project's future. Had they been wrong all this time--would the physics gameplay really be as revolutionary as they had once thought? Were the dramatic sequences going to bore players to death? What seemed like brilliant choices three years ago were now being questioned. The failed proof-of-concept reel was an agonizing reminder that Half-Life 2's success wasn't a foregone conclusion.

The disappointment was amplified by the fact that Valve didn't want Half-Life 2 to just be a good game--it wanted the game to blow the competition out of the water. "Look, getting game of the year won't be good enough for guys like [designer] Steve Bond," Newell says. "If Half-Life 2 isn't viewed as the best PC game of all time, it's going to completely bum out most of the guys on this team." So, if anything, the failed proof of concept meant that the team would want to double its efforts going forward. They weren't going to give up, they were just going to work harder and longer until the game was in fighting shape. "That was the hard part," Newell admits. "We had already been working on this thing for bloody forever and now we couldn't see the end point anywhere in sight."

The seemingly invincible Valve had stumbled in a very dramatic--yet very private--way. According to Newell, the mood at Valve took a turn for the worse: "Guys were walking around the office saying, 'Oh my God, what if we actually f*** this up?'"

Try, Try Again

Once the initial disappointment subsided, some of the team realized that they may have overreacted to the failed proof of concept. "In retrospect we crammed a lot of technology into that demo," Guthrie says. He was particularly happy that striders, massive 60-foot robots with gazellelike legs, were now technically possible. Others at Valve were even more philosophical about the disappointment. "I find that in any creative process you say, 'I've forgotten why I'm doing this,' about halfway through," Laidlaw says. "The key is that you just have to keep plowing through and eventually you end up with the thing you pictured originally and that much more."

So that's exactly what the team did: They put their heads down and worked on a new proof-of-concept reel during the summer of 2002. The team definitely felt internal pressure to get the project back on track but there was absolutely no pressure from the outside. There were no publishers threatening to cut off funding or marketing executives demanding that the game be announced on a certain date. Valve was free to do as it pleased.

In a way, the failed proof-of-concept reel mirrored another failure in Valve's past. In the fall of 1997, Newell played through an early version of Half-Life, only to realize that the game wasn't any fun to play. So Valve scrapped the game and almost completely redesigned it in 12 months. Choices like these are often the difference between a good game and an exceptional one. Newell says Valve will always err on the side of redoing things if a game isn't up to snuff. "We don't have some producer from the packaged-foods industry coming in here and saying, 'Ship this in six weeks or else!" he says.

True. But most game developers also aren't in Valve's position, where Newell has enough money to fund a game's development out of his pocket, if he so pleases. So is it really fair to hold other developers to the same standard as Valve? Ask Newell this question and he grows agitated. "Any developer who bitches about, 'Oh, our publisher cut off our money,' or, 'The publisher made us ship the game early,' doesn't get it," he says. "That's the interesting problem you have to solve as a developer. If you don't, well, you'll be perpetually screwed." But how do you solve the problem? Newell cites the development of Counter-Strike, where a young college kid in Vancouver made a Half-Life add-on, as a prime example. "You bootstrap," Newell suggests. "The Counter-Strike guys didn't have some sugar daddy show up and drop a huge wad of cash in their lap. You have to be creative."

"The Counter-Strike guys didn’t have some sugar daddy show up and drop a huge wad of cash in their lap. You have to be creative."Gabe Newell on how game developers should get their start

Valve wasn't beholden to a game publisher, but it did feel beholden to the fans. And by the summer of 2002, the team began to realize that Newell was right--the March proof-of-concept reel probably would have disappointed the fans. "The whole Dr. Kleiner's lab sequence way too long and boring," Van Buren admits. Laidlaw says that back in March the team had yet to strike the right balance between dialogue and gameplay. "It's like what Hitchcock said: 'Pictures of people talking is not a movie,'" he says. "We are building a game with interactivity and gameplay. The dramatic scenes with the characters are important, but they have to be in service of the interactivity and gameplay."

Now the question was if Valve could learn from its mistakes and get the project back on track.

The Devil Is in the Details

The summer of 2002 was a tough slog for the team. Until a new proof of concept was completed, there was no knowing when--or if--the project would get back on track. But one thing was for sure: Expectations were sky-high for the sequel to Half-Life. And after more than three years of hard work, the team wasn't about to let the fans down.

By early September, the team had completed what it judged to be a greatly refined proof-of-concept reel. The tools for both level design and character animation had improved, so it was now easier to prototype gameplay ideas. The reel included new and improved gameplay sequences: A buggy race along the coast of City 17, an encounter with headcrabs on a pier, and the pièce de résistance, a strider attacking the downtown area of City 17. Many of the gameplay sequences were actually refined versions of what had been shown in March. The sequence in Dr. Kleiner's lab was still included, but it was now just a few minutes long.

The new demo was set to be presented on a Monday in September. The weekend before, the team worked around the clock to pull it together. Yet by Sunday night the team started getting cold feet. No one was quite sure if the reel was going to be good enough. When Jay Stelly left the office around 7pm on Sunday, he remembers being uncertain whether the new proof of concept would pass muster. "When I left the office the strider was shooting at a bridge and there were explosions," he recalls. "It looked OK, but I didn't think it was that impressive."

Fifteen hours later, the team presented the new proof-of-concept reel to Newell. Stelly was amazed at what had changed overnight. "Now the physics of the bridge breaking were in, the people were running across the catwalk, and the strider was ducking under the bridge as it attacked," he recalls. "It just seemed like we finally had a game and it came together overnight." The rest of the team--including Newell--agreed with Stelly's assessment. The game was back on track.

Newell briefly toyed with announcing the game in the fall of 2002 to celebrate the fourth anniversary of Half-Life's release. But those plans were called off because he didn't want to announce the game until he had a ship date. As a result, the employees went through another holiday season without being able to tell their relatives what game they were developing. "When I went home for Thanksgiving, my relatives asked me, 'So how did that game you were working on last year turn out?'" Stelly says. For the fourth consecutive year, he had to admit he was working on the same game. And he couldn't even tell them the name of it.

The secrecy around Half-Life 2, however, would soon be lifted. Valve was about to move into full-scale production. Newell assembled the team in October of 2002 and delivered a rallying call: "We have to prepare to announce the game at E3 and get it out by the end of 2003." There was no turning back now.

The Cabals Move In

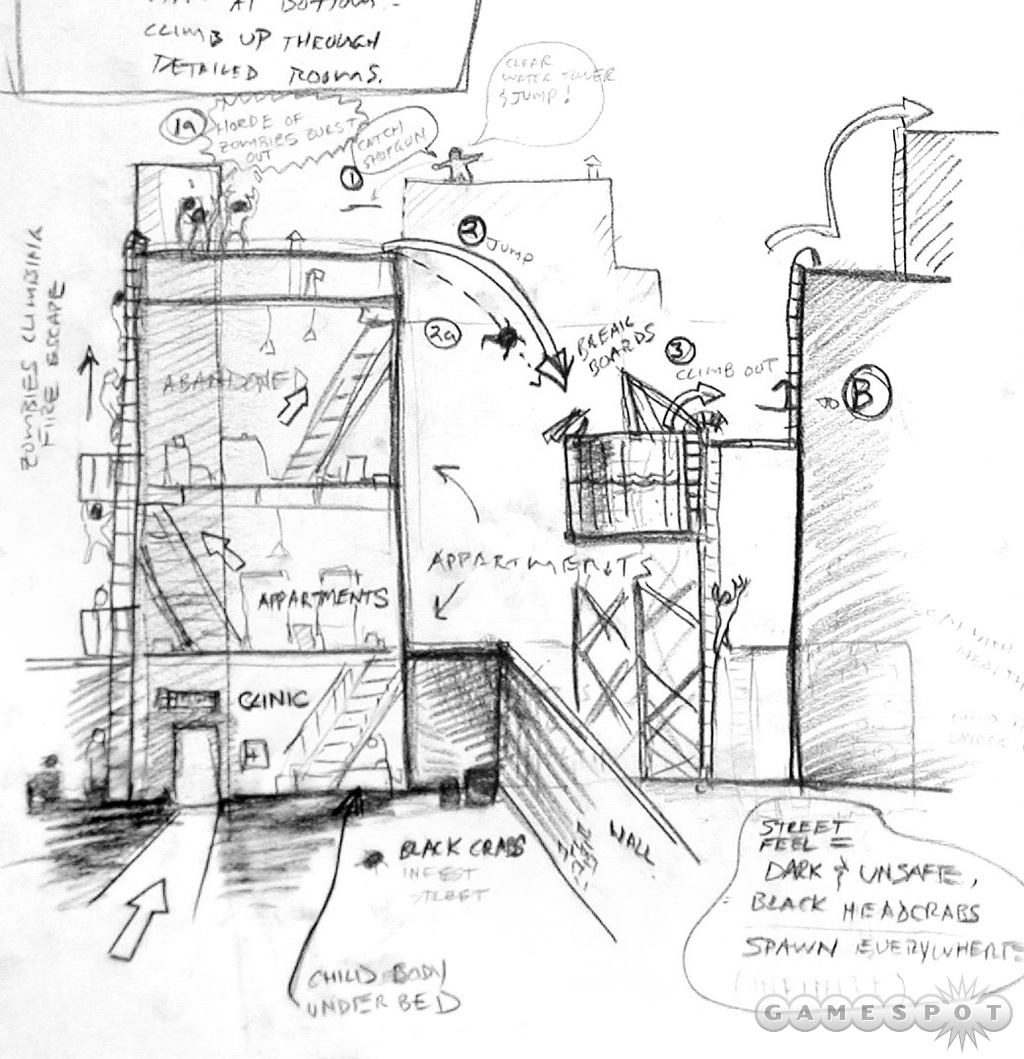

The immense scope of City 17 meant that no one designer could oversee the entire game. So, as was the case with Half-Life, Valve employed its "cabal" design process, in which small design hives tackled different parts of the city. For Half-Life 2, there were three main cabals of up to six designers. Each cabal worked in a large office that looked a bit like the bridge of a submarine. John Guthrie's cabal--which worked on the game's canal section and Ravenholm, a zombie-infested part of town--consisted of his longtime friend Steve Bond (they first started working together at age 16), Dario Casali, and Tom Leonard. "I actually see these guys more than I do my girlfriend," Guthrie jokes. On second thought, maybe he isn't joking.

|

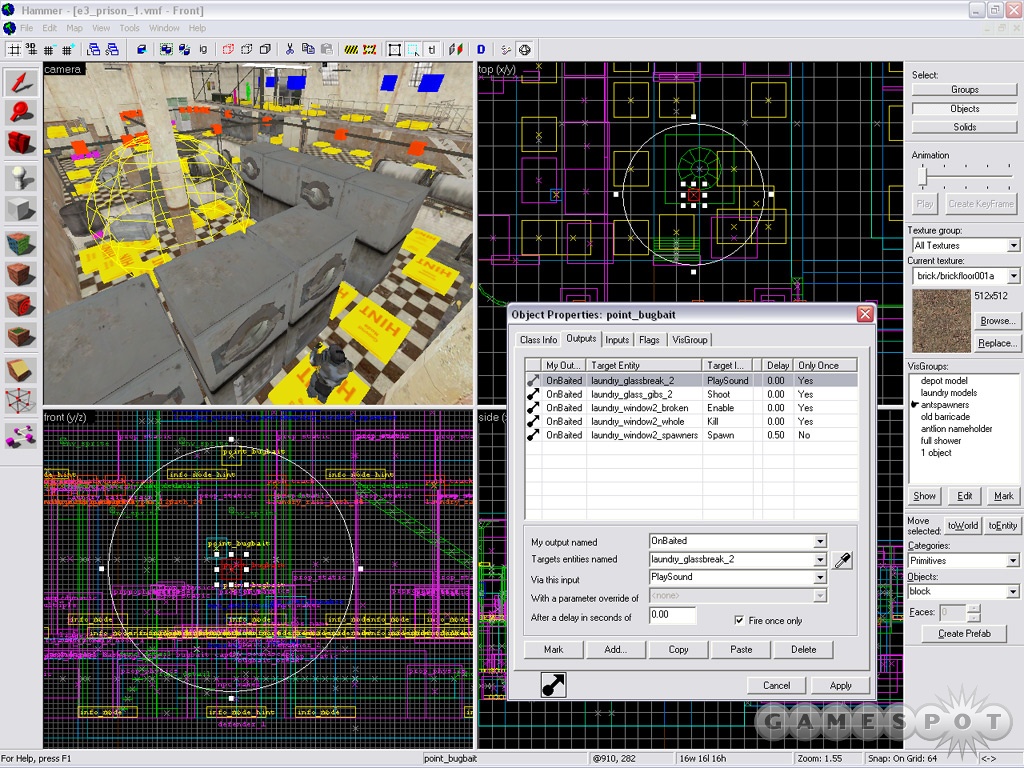

The cabals designed levels much like they designed levels for Half-Life, with one notable exception: Level design was separated from art for Half-Life 2. In other words, the designers first fleshed out the gameplay before the artists began to gussy up the levels with beautiful textures. This new production pipeline let the cabals rapidly create new content. (The first pass at a map was called an "orange map" because all the level textures would be the same shade of orange). The cabals even designed the scripted elements of the game using simple text bubbles that would pop up on screen. So in the first pass at a level, the cabal might put in a text bubble that said, "One day you'll be able to drive a jeep and jump this ramp." This allowed the team to perfect the gameplay and work out story issues like pacing long before an artist touched the level. The orange maps even helped the cabals when it came to designing the physics of the gameplay." Before you could hoist up cars and drop them on enemies, you were hoisting up orange cubes," Guthrie says.

By early 2003, the cabals were cranking away on game design, working on countless levels and collaborating with Laidlaw to make sure all the levels would fit into the larger storyline. Still, there were struggles during the early days of production. Namely, the core game technology was unstable and unfinished. Unlike Half-Life's development, in which Valve licensed the fully working Quake engine and built a game on top of it, Half-Life 2's development employed the Valve-created Source engine, which was a constant work in progress. In-game vehicles, for instance, weren't working when the cabals first started the design. That led to much frustration. "We needed levels built for vehicles but we didn't know how the vehicles would work," Newell says. "For instance, we didn't know how high off the ground the buggy could bounce." But since vehicles played a major role in the game, the cabals had to make assumptions about how they'd work. "Unfortunately, those assumptions often turned out to be wrong," Newell says.

Despite these early concerns, Newell had a meeting late in late February of 2003 to discuss the state of the project with Yahn Bernier and Stelly. Newell still planned to show the game at E3 and ship it later in the year. But now he wanted to get more precise. He looked at the schedule and made a bold prediction: The game could be finished in September. Then his calculus got even more specific: The game would ship on September 30, 2003. While he won't confirm it, many have speculated that Newell set such an aggressive target to make sure the team stayed motivated during the summer. He maintains that when he made the September 30 decision, he fully believed the game could be done by that date.

"The good news was that we actually had a ship date--a date to look forward to."John Guthrie’s initial thoughts on the September 30, 2003 ship date

Newell next announced the ambitious date to the team. Many of them were surprised by Newell's aggressive target. "The good news was that we actually had a ship date--a date to look forward to," Guthrie says. But then the harsh reality set in: There would be no room for error. In fact, there would hardly be any room for sleep. "I figured there were enough hours left between where we were in February and where we needed to be in September to finish the game," Guthrie says. "But I wasn't exactly looking forward to using all those hours to hit that date."

The Half-Life 2 team was about to enter a very serious crunch mode--a period of intense development that would last until the game was finished, hopefully in mid-September. The days of working on a project with no time pressure and an unlimited budget were a distant memory. Newell had now fast-tracked the game's release. It was going to be a very stressful summer at Valve.

The Potemkin Village?

It's March 2003 and Gabe Newell looks like he's about to start a shadow-puppet show. Sitting in the conference room at Valve, Newell has raised his right hand and clasped his thumb to his index finger to make a mock mouth. "I've sort of been having this internal conversation with our fans for years," he says while looking at his hand. "So I have to pretend my hand here is a fan and I need to guess what they are going to think of Half-Life 2." Newell goes on to say that he's sick and tired of guessing what the fans will think. He's ready to show them the game and get their reaction. "At E3 I'm finally going to be able to look the fans in the eyes and say, 'OK, what do you guys think?'" he says.

"We looked at the cost of doing a demo like that and said, 'No way in hell."Ken Birdwell on the aborted E3 demo concept

How would Valve unveil the game at E3 2003? At first Newell wanted the team to create an extensive 30-minute demo that would feature Alyx, the main female character, guiding the audience through a science lab that showcased the Source technology. Then, halfway through the demo, the lab would suddenly be attacked and the player would have to escape alongside Alyx. It sounded like a great way to break the fourth wall and show off Valve's character technology. But in the weeks leading up to E3, it became clear there was no time to create such an elaborate demo. "We looked at the cost of doing a demo like that and said, 'No way in hell,'" Birdwell remembers. "If we were shipping September 30, everything that was going to be at E3 had to be something we could ship."

The fans at E3 would have no idea that Valve had dramatically scaled back its plans for the demo. In place of the Alyx demo, Valve showed off a number of the proof-of-concept demos, along with a few new snippets of gameplay. The demo started off with everyone's favorite character, the G-Man. Valve even thought up a brilliant way to add some dramatic flair to the demo: At first the G-Man looked as he did in the original Half-Life. Then the image changed to the new photo-realistic character model for Half-Life 2. The contrast between the two character models was a masterstroke--it showed the audience just how far Valve had come in five years.

But it didn't matter if Valve thought its demo was cool. Newell was more interested in the fan reaction. As soon as the first E3 demo was finished, he turned to the audience and asked a simple question: Is this a worthy successor to Half-Life? Time and again, the answer was yes. "I can't tell you how much that meant to me," Newell says. "Our fans said, 'We trusted you to do something very cool and exciting and this lives up to our expectations.'" Newell would keep asking the same question for all three days of the show. Every time he'd get the same response.

Half-Life 2 was the buzz of the show. In the weeks following its debut, the Game Critics Awards: Best of E3 2003 awarded it the highly coveted Best of Show award. But just like with any popular demo at E3, competitors and some members of the press remained skeptical about what Valve had shown--especially in light of the promised September 30 ship date.

The line of reasoning went like this: If the game really were coming September 30, that meant Valve had to finish the game in the summer. So why didn't Valve let people actually play the game at E3 in mid-May? The physics gameplay looked interesting, but competitors said that it could never actually work in a game like that--it would be a design nightmare to let players have so much control. The skeptics wondered if Valve had hoodwinked the entire industry with an elaborate tech demo that would never become a game. Was City 17 actually a Potemkin village, an elaborate fake town like the one Russian field marshal Grigori Aleksandrovich Potemkin supposedly created to impress Catherine the Great on her tour of the Ukraine in the late 1700s?

Valve had heard all this before--it was sour grapes, it thought. And Newell had just one message for the doubters: We will see you on September 30. Or maybe not. As soon as Newell returned from E3, he took a long, hard look at the team's progress. And he soon reached a heartbreaking conclusion.

The Sweater Falls Apart

The post-E3 celebration at Valve was short-lived. With Newell hell-bent on shipping the game on September 30, there wasn't time to celebrate or take a vacation. But it might have been a good time for a reality check. Even though Newell kept talking about the September 30 release, the team knew there was no way the game could make that date. No one, however, had the heart to tell Gabe. "In retrospect I could tell things were off with the schedule when I came back from E3," Newell admits. "I'd sit in meetings and when I'd talk about September 30 the rest of the team would just start looking at the ceiling."

"In retrospect I could tell things were off in the schedule when I came back from E3 [2003]."Gabe Newell

But at the time Newell didn't pick up on the signals. He just kept talking about how exciting it would be to ship the game on September 30. "I'd say we needed to get the localization going for the dialogue to meet the September date," he recalls. "But the dialogue wasn't done so we couldn't start that." Slowly Newell began to realize that something was wrong. "We hadn't put a bunch of items on the list that needed to be there--and the items on the list were taking longer than expected," he says. Newell felt backed into a corner: He had been so absolute in setting the September 30 date that he felt an obligation to deliver the game as promised. When he finally realized the game was unlikely to make the date he called a meeting with the team. "We all sat around and said, 'OK, what the hell do we do?'" Birdwell remembers.

One option considered was to drastically cut the size and scope of the game. "We looked at the game and said, 'OK, if we cut this in half can we ship it in time?'" Birdwell says. If Valve took that path it would mean cutting the most difficult--and potentially memorable--scenes out of the game. Since vehicles weren't working yet, the Jet Ski levels would have to be cut. The dramatic scenes would also have to be scaled back because they were still too hard to animate. "So we went back to Gabe and said, 'OK, here's what we can do to meet your date or a date close to it: We can cut all this stuff and ship a game that's half of what it's supposed to be,'" Birdwell says.

"There wasn’t one big moment where we said, ‘S***! We’re going to miss September 30th.'"Gabe Newell on the missed release date

Not surprisingly, Newell told the team that they shouldn't compromise the game design to meet a release date. And that's when reality set in: The game wasn't going to ship on September 30. "There wasn't one big moment where we said, 'S***! We're going to miss September 30," Newell says. "It was more like slowly pulling the thread of a sweater until eventually the whole thing falls apart." Newell now admits that by July it was "pretty obvious" the game wasn't going to ship in September. But Valve kept the change of plans quiet. No one outside the company knew the game was going to miss its widely publicized release date.

Except maybe the executives at Vivendi Universal Games. On July 29, 2003, Vivendi informed retailers that Half-Life 2's release date had been moved from September 30 to "holidays 2003." The fans on the Internet hit the roof. Had Half-Life 2 really been delayed? One webmaster e-mailed Newell for confirmation. He received a response that has now become legendary among Half-Life fans: "First time I've heard of this," Newell wrote. The fans read that response as Newell confirming the game was still on for September 30.

In August, Valve continued to confirm the September 30 release date in a very public and direct fashion. On August 24, Valve said that the "release date's unchanged" and went so far as to confirm the game would come out worldwide on September 30. Perhaps the most telling comment, however, came on August 27, when Valve's Greg Coomer told a journalist at the ECTS trade show in London that, "It'll be tight, but Half-Life 2 is still on for a September 30 ship."

The fans began preparing for the gold announcement in early September. They started discussing what they would do on September 30. Would they take the day off from school? Call in sick to work? For months everyone had been anticipating the September 30 date. And while rumors kept swirling that the game wouldn't ship on time, Valve insisted it was right on schedule. Even as late as September 18, a Half-Life fan visited Valve and asked Newell about the September 30 release date. The fan must have been skeptical--wouldn't the game have to be in duplication by now to ship in only 12 days? Newell looked the fan square in the eyes and still wouldn't confirm the delay. But he hedged for the first time. "We'll see," he said.

Broken Promises

Gabe Newell loves his fans. He answers their e-mails all the time. He even answers their weird e-mails. Like the one in which a fan asked Gabe if he'd trade some sexual favors in return for an advance copy of the game. ("Whose sexual favors?" he wrote back. "If they are Cameron Diaz's, and you get my wife to agree, then you're on.") Newell says he gets more than 400 e-mails a day from fans who want to check in with him and see how things are going.

Sometimes the fans even call him at home--at 3am. He briefly indulges them in conversation and then politely asks them to call at a more reasonable hour. For Gabe almost everything at Valve is done for "the fans." You'd be hard-pressed to find another developer in the game industry who spends more time writing to fans, posting on forums, and even giving fans tours of the Valve office. Why spend so much time talking to the fans? "They pay the bills," Newell says.

Why would a guy who cares so much about his fans keep them in the dark for months on end about the state of Half-Life 2? During the summer of 2003 Newell practically stopped communicating with the fan community. No one knew what to think. But they trusted Gabe. If the game wasn't going to ship on September 30, the fans figured that Gabe would come out and tell them that. Or at least he'd admit that the game might be delayed. But Gabe said nothing and the fans took that to mean good news.

"The previously announced September 30 release date for Half-Life 2 is being pushed back."E-mail from Valve on Sept 23, 2003

But on the night of September 23 the truth emerged. Exactly one week before the game was supposed to ship, Valve released a short statement to the Shacknews Web site. "The previously announced September 30 release date for Half-Life 2 is being pushed back. We are currently targeting a holiday release, but do not have a specific 'in store' date to share at this time."

The fans were stunned. A month ago Valve was confirming a September 30 ship date. And now Valve claimed the date had been pushed back? The fans didn't understand. Why did Valve create a false sense of hope? Why did they string us along for so long? Why would Valve, a company that seemed to do everything for "the fans," turn around and bite the hand that had fed it so well?

As September 30 approached, Newell turned down interview requests, and no one at Valve would elaborate on the state of the game. The fans were enraged. After all the hype and all the buildup, they began to wonder what else Valve might have been lying about. Perhaps the cynics were right--maybe the E3 demo really was a sham or a facade. Some fans remembered Team Fortress 2, a game that was announced at E3 in 1999, won countless awards, and then disappeared shortly afterward. Was Valve up to its old tricks again--was Half-Life 2 going to disappear like Team Fortress 2? The webmaster of one Half-Life fan site posted a bitter missive on Valve: "The bottom line is this: I'm not a fan of Valve anymore. I don't believe a damn thing they say and I'm sick of their bulls***." Valve, the company that had created one of the greatest PC games of all time, now seemed to have pulled off one of the greatest cases of deception ever seen in the game industry.

The fans felt burned. They wanted answers. The problem was that Valve wasn't giving any. Until now.

Gabe Comes Clean

Game release dates slip all the time. In fact, it's hard to think of a cutting-edge, genre-defining game that didn't have its release date moved back at least once. Even the original Half-Life shipped a year later than first projected. So why did the fan community whip itself into such a frenzy over the Half-Life 2 delay? It boiled down to this: The fans weren't upset that the game was delayed, they were upset over the way the delay was handled by Valve. In the weeks following the delay announcement, Valve wouldn't say anything to explain the delay. Indeed, until now, Gabe Newell has never publicly commented on the release-date fiasco.

But he wants to set the record straight--to explain to the fans why Valve did what it did. It's not, however, an easy thing for him to do. Ask him about the debacle and his first explanation is utterly unsatisfying. "I was just dumb," he says bluntly. So you ask him again. This time he delivers a highly technical and emotionally distant answer: "I made the decisions I had to make based on the problems that were apparent and the questions that needed to be answered."

But finally, after much prodding, Newell begins to explain why Valve seemingly misled the public for months. First, he wants everyone to know that those initial September 30 promises haunt him to this day. "Listen, I feel absolutely terrible about the date fiasco," he explains. Then he lists every possible adjective of regret he can conjure: "I feel totally guilty and embarrassed and ashamed and humiliated about what happened."

So what did happen? As Newell and the team have explained, by July it was obvious that Half-Life 2 would not be finished in time for a September 30 release. So why was Valve still telling the public in late August that the game was on schedule? "We were paralyzed," Newell says. "We knew we weren't going to make the date we promised, and that was going to be a huge fiasco and really embarrassing. But we didn't have a new date to give people either." In other words, Newell didn't want to announce the delay until he had a new official date to announce. It's that simple. "So I decided we should just stay quiet," he says.

Still, there's a difference between staying quiet and confirming a ship date that you know to be incorrect. Newell says that, in retrospect, he may have made the wrong decision on this front. At the time, however, he didn't want to announce the delay until he had something better to tell the fans. "I didn't want to go to 'when it's done' or announce 17 different dates over the next few months," he says.

"We were paralyzed...We knew we weren’t going to make the date we promised and that was going to be a huge fiasco and really embarrassing." Gabe Newell on the missed release date

So by mid-summer he was in an awkward situation: He had dug himself into a hole by loudly proclaiming the September 30 ship date. Now he knew he was going to miss that date. So what did he do? Like people sometimes do in an embarrassing situation, he stalled. He thought that by saying, "The game's still on schedule," he could quickly move on to other questions in interviews and not have to confront the slippage. But as September 30 approached, Valve didn't have a new date, and Newell finally had to fess up about the delay.

Looking back on those months, would Newell change anything about how he handled the situation? He says yes. "If I learned anything, it's just that we should be more open with the community--to tell them what we know and don't know," he admits. Indeed, no one asked Valve to promise the game on a specific date. That was Newell's choice. And it's a choice he now regrets. "Yeah," he says with a chuckle. "In retrospect I probably should have just said, 'When it's done.'"

On Top of the Rock

If Gabe Newell had his way, he would have spent September 30, 2003, lying low at the Valve office. He was deeply embarrassed by the slipped date and frustrated that the fans were berating Valve on the Internet. In other words, he just wanted September 30, 2003, to quietly pass. Unfortunately, that wasn't a possibility. He had a prior obligation: the Half-Life 2 launch party, which graphics-card manufacturer ATI had scheduled months in advance--fully assuming, of course, that the game would ship on September 30.

ATI, which is rumored to have paid more than $6 million to Valve as part of a broad endorsement deal, planned a massive fete to celebrate the launch of the game and a new ATI graphics card. ATI rented out the entire island of Alcatraz in San Francisco and planned to host the party inside the prison. Newell wanted to pull out of the event but couldn't. It was an obligation to a business partner--a partner that was "none too pleased we missed our date," he says.

On the afternoon of September 30, Newell arrived at Pier 41 in San Francisco and boarded the ferry that would take him to Alcatraz. It must have been his worst nightmare: to be trapped on an island with the world's gaming press, a group that wanted nothing more than to pelt Newell with tough questions about Half-Life 2's release date.

At about 8:30pm, Newell, dressed in a red polo shirt, walked onto a makeshift stage inside the prison. No one knew what he was going to say. Was he going to address the botched release date? Was he going to show a new demo of the game? This was Newell's chance to win back the fans he'd alienated and misled. All he had to do was say he was sorry and show that the game was nearly done. But he didn't do that. In what seemed like a carefully prepared speech he praised ATI and then showed a very brief "benchmark" demo of the Source engine. Half-Life 2 was nowhere to be seen.

"It wasn’t me saying, 'You know, the Doom 3 engine is looking really good right about now.'"Gabe Newell on a leaked e-mail message from Valve

The press was floored. Here it was September 30 and Valve still wasn't showing Half-Life 2 to anyone? Not even a level? Once again rumors started swirling about the state of the project. Would it even come out in 2003? Newell, who desperately wanted to get back to Seattle, was briefly cornered by GameSpot as he tried to leave the prison. "I hate release dates," he said. "No matter how hard we try we screw them up." And with that comment Newell slipped out the door and caught the first ferry back to the mainland at 9:30pm.

Newell just wanted September 30 to end. And who could blame him? Six months earlier, this was the date he promised everyone they'd be playing the game. And now no one was playing the game. No one, that is, except a young man in southern Germany.

An Unthinkable Crime

It all started one September day in 2003. That's when the hard-drive light on Gabe Newell's PC started flashing at bizarre times. The problem persisted even after he reformatted his hard drive and ran a virus scan. So he sent an e-mail to check if anyone else's PC was on the fritz. "Has anyone seen anything weird going on?" he asked the staff. No one responded.

Then something even weirder happened. A copy of an e-mail between Newell and Valve programmer Dave Riller appeared on the Internet. It was an innocuous e-mail about Counter-Strike. "It wasn't me saying, 'You know, the Doom 3 engine is looking really good right about now,'" Newell jokes. But how did the private e-mail end up online? Newell walked down to Riller's office and asked if he had forwarded it to anyone. Riller said no. "All of a sudden I got this sinking feeling," Newell says. He started to worry that someone had figured out his e-mail password. He quickly changed it. Problem solved? Not quite. "In retrospect we were looking for bruises when our throats had already been cut," he says.

As Newell looked into the situation more closely, he came to an alarming conclusion: "We were f***ed." He found odd software installed on his machine. There were hidden hard-drive partitions. The network activity on Valve's servers showed uncommon spikes. When he began to check other computers, he found at least 13 that had similar software installed. Valve's security had been compromised. Racing around the office, he told everyone to disconnect their computers from the Internet. He started pulling wires out of walls, shutting down computers and effectively cutting Valve off from the outside world.

It was too late. As soon as the hacker realized that his access had been cut off he started releasing to the Internet parts of what he had been able to obtain from Valve's network. On October 4, the first bomb dropped: The entire source code to Half-Life 2 was let loose. Newell was furious, but he also didn't know if it was the start or the end of the hacker's plans. "It's not like someone hands you a card that says, 'This is how screwed you are,'" he says.

"Then people started using the game to compose their own screenshots of Dr. Kleiner performing [oral sex] on Alyx. It's basically your worst nightmare."Gabe Newell on the leaked copy of Half-Life 2

The source-code leak turned out to be only the opening salvo from a man calling himself "Osama Bin Leaker." (It would later be learned that the hacker was "Axel G," a 21-year-old man in Germany). On October 7, only three days after the source code leaked, the second bomb dropped: A playable version of the game was released, including portions of the E3 2003 demo. Newell didn't know what to think--was the worst over? "It just felt like each day things kept getting worse," he recalls. "First the source code. Then the game. And then people started using the game to compose their own screenshots of Dr. Kleiner performing [oral sex] on Alyx. It's basically your worst nightmare."

The theft of the game and its release to the Internet was a crushing blow for Valve. But it had an even worse aftershock: It exposed the real state of the game's development as of September 19, only 11 days before the scheduled release. In his notes accompanying the release, Osama Bin Leaker said, "I'd like to point out this is what you wanted Valve to release on 9/30/03." And then he added a pithy footnote: "I'd like to point out the E3 demo was one big fake by Valve."

"For months Newell hadn’t told anyone about the state of the game. Now he was getting his comeuppance-- the game was speaking for itself."

For months Newell hadn't told anyone about the state of the game. Now he was getting his comeuppance--the game was speaking for itself. Those who obtained the illegal release found a game that was nowhere near finished. While it was uncertain if the leaked version fully represented Valve's progress, some insensitive fans took pleasure in the effects of the code theft. Valve got what it deserved for lying to us, they claimed.

Conspiracy theories started bouncing around the Internet. Some fans advanced the theory that perhaps Valve deliberately leaked the code to buy itself more time and deflect attention from the delay. (This, of course, was not true). Still, it was strange that the game leaked only days after September 30. Newell says the hacker's claim that he released the code to prove Valve was lying about September 30 was, as he puts it, "utter bulls***." What triggered the code release wasn't the date," Newell says. "They knew we had discovered them in our network so they were just going to go ahead and release what they had. They just made up a goofy excuse."

The damage had already been done. At Valve no one knew what the code theft meant for a project that had been through its fair share of twists and turns. Would this unthinkable crime derail the game? Newell had no idea how to measure the impact of what had just happened. And worse, the team members--the people who had spent more than four years tirelessly working on the game--were absolutely crushed to see their unfinished work exposed to millions.

One young designer brought his concerns right to Newell in his office. "Gabe," he said, "is this going to destroy the company?"

Picking up the Pieces

Gabe was mad. No, he was more than mad. He was furious with whoever perpetrated this crime against Valve. It was one thing for the fans to make fun of him online. But as soon as he saw that his designers, artists, and programmers were worrying about the future, well, that's when he really went off. For years Newell had worked to make Valve a safe creative haven for the best and brightest in the business. He was the video game equivalent of the X-Men's Professor X, running his own school for the gifted. While the code theft might have meant millions in lost revenue for Valve, Newell was much more concerned about the morale and well-being of his team.

So he put on a brave face. He called everyone into the conference room and displayed remarkable sangfroid. "You know guys, every id release has leaked early and it's been no big deal,'" he told the disillusioned team in an attempt to comfort them. Then he tried to turn lemons into lemonade. "We've made it through all this," he told the team. "How much worse can it get?"

Keeping his team in high spirits was only part of the problem. Newell also had to figure out just who had compromised Valve's security and stolen the game off the network one byte at a time. He called the FBI to start an investigation. He also kicked off his own investigation by posting a message to fans online--yes, those very same fans that were furious over the missed release date. "Ever have one of those weeks?" he asked in a forum post. Newell went on to appeal to the Half-Life community for help in tracking down the hacker.

"We lost a fair amount of time because of the theft."-- Gabe Newell on the impact of the code theft

Newell also had to keep his team focused on the task at hand: finishing Half-Life 2, a game that was now costing Valve more than $1 million a month to develop. While there was no way the game could be finished in 2003, Newell wanted to make sure the project didn't lose momentum. "We lost a fair amount of time because of the theft," he says. But that lost time wasn't necessarily because the game had to be reprogrammed. It was more due to the team losing focus for a number of weeks. "It was sort of like running this race and you fall down," he says. "You eventually get back up and probably run just as fast as you did before. But for a while you are stunned and just staring around, wondering what just happened."

The 2003 holiday season was supposed to be a time of great celebration and relaxation for Valve. Half-Life 2 was supposed to be done and on store shelves. But now the employees would return in January and face 20-hour workdays with no clear sense of when the game would be finished. "By Christmas there were still a lot of empty spots in the game and really low density to the levels," Laidlaw says.

Would 2004 be Half-Life 2's year? Newell, now the eternal pessimist, couldn't see any way the game would be done before the summertime. But he didn't want to say anything to the public just yet. One thing was for sure: He didn't want a repeat of the September 30 fiasco.

Hello, Gabe

When the team returned to work in January 2004, it had been in crunch mode for almost a year. Worst of all, there was no sign the stressful development period would end anytime soon. There was, however, a silver lining: Improved level design and animation tools meant that it was now easier to produce game content. "By January there weren't any really interesting problems left for us to solve," Newell says. He even went so far as to calculate that Valve could produce about three hours of quality gameplay per month. "I finally got the sense that we were turning the crank on this project in a major way," he says. While Newell wasn't confident enough to predict a release date, he started to believe an "alpha" version--where the game could be played from beginning to end--would be ready by March.

There was other good news as well. While Birdwell's in-game characters had always been visually impressive, no one was sure how the in-game acting would blend with the fast-paced action. But in early 2004 the game's dramatic scenes started coming together in a powerful way. For years Laidlaw and Van Buren worked on honing the script for the game, which ended up amounting to more than 150 pages of dialogue, or about two hours of fully animated in-game scenes. (The original game had only 19 pages of dialogue). They even hired an impressive Hollywood cast of actors to play a number of key roles, including Robert Culp as Dr. Breen, the game's antagonist. (Robin Williams expressed interest in voicing the alien character Voiteguart, but scheduling conflicts prevented him from playing the role). Newell finally got his wish: The characters weren't robots--they acted, talked, and moved like real people.

Even the fans seemed to be coming back around in early 2004. Many of them realized that perhaps they had overreacted in the wake of the September 30 release-date fiasco. One even e-mailed Newell in January 2004 to express concern about his health. "You seem to have taken on some weight [in your recent media appearances]," the fan, MJA Lebbink, wrote. "All the fanboys are going to kill me for saying this, but if delaying HL2 is what it takes to keep you healthy by all means do so. I'd rather see HL2 in 2005 and you healthy and making more great games than a HL2 today and no more Gabe in the future." Newell, after reading the e-mail, sent a response. "I appreciate the sentiment," he wrote.

The e-mail from MJA underscored the unique relationship Newell maintained with Valve's fans throughout the project. Over the course of Half-Life 2's development he gave many tours of Valve to fans and responded to thousands of e-mails. But there was one e-mail that stood out from the rest. Newell found that one sitting in his inbox the day after Valentine's Day.

I'm Getting My Crowbar

On February 15 a strange e-mail arrived in Gabe Newell's inbox at 6:18pm. The subject line was blank, but the text of the e-mail from "Da Guy" was rich in detail. "Hello, Gabe," the author began. He then proceeded to admit that yes, he was the hacker who had broken into Valve's network. In fact, he had been inside Valve's network for about six months, watching the game's development on a daily basis. He claimed he never intended to harm Valve with his hacking. Instead he just wanted to observe Half-Life 2's development because he was such a huge fan of the original game. And then, unbelievably, he even offered his compliments to Newell and the team on their amazing development skills.

"I'm getting on a plane and I'm bringing my crowbar with me." Gabe’s reaction to an e-mail from the hacker who attacked Valve

At first Newell didn't know if the e-mail was some sick joke or an authentic mea culpa. But then, at the end of the e-mail, the hacker provided proof that he was legit: He included two files from Valve's network that hadn't been released to the public. One was a Microsoft Word document that detailed Valve's plans for the E3 2003 demo. That was all the evidence Newell needed. This was "da guy" who had screwed them. His first reaction: "I'm getting on a plane and I'm bringing my crowbar with me."

But Newell was smarter than that--he decided to play along with the hacker. So two days later he responded at 5:39pm. He did his best to seem calm and collected, stripping all emotion out of his e-mail. He wrote that he "need[ed] to run home to deliver chicken yakisoba to the starving children," but he'd "take a look at [the files you sent] tonight." Then he ended his brief e-mail to "Da Guy" with a question: "So it's cool that you are clearing up the mystery for us, but why are you doing it?" he asked.

Over the next few weeks, Newell and "Da Guy" would continue their e-mail conversation. "He had the typical hacker mentality," Newell says. "He thinks, 'If I can get away with it, you deserve it!'" So Newell tried playing to the hacker's line of reasoning: He told him how cool it was that he was able to break into Valve's network. In fact, it was so cool that Valve wanted to hire him as a special security consultant to protect Valve from any future attacks. "Da Guy" couldn't believe it! Newell was offering him a job at Valve headquarters in Bellevue, Washington.

As the e-mail exchange continued, "Da Guy"--whom Newell came to know as "Axel G," a 21-year-old from the southern German state of Baden-Wüerttemberg--started preparing for his "job interview," which would take place at Valve headquarters in Bellevue. Unbelievably, he even asked Newell if he could also fly over his dad and his brother for the occasion. Newell said that sounded great--he'd even give them all a tour.

"[Newell] told the hacker how cool it was that he was able to break into Valve networks. So cool, in fact, that Valve wanted to hire him as a special security consultant."

There would, of course, be no job interview. Newell had convinced the hacker to fall for the oldest trick in the book. As soon as "Axel G" was to walk off the plane in Seattle, the FBI would be there waiting to place him under arrest. Those plans changed at the last minute, however, when the German government got wind of Newell's plan. The government objected to Valve enticing a German national out of the country solely so he could be arrested on US soil. The German authorities wanted to handle the arrest directly. And they did just that: "Axel G" was arrested this spring in Germany and now faces charges not just for hacking into Valve, but also for developing a number of pernicious viruses, including the Phatbot worm. "He's really a pretty evil guy," Newell says. "He built up these distributive productivity tools for hackers so you can send off 100,000 machines to look for unprotected IP addresses."

The arrest of "Axel G" solved the mystery of who hacked Valve and why. Now all that remained was solving the other mystery on the project: Was Half-Life 2 going to be any fun to play? In early March the team would solve that mystery by playing through a rough version the game from start to finish. Would the game come together like a masterpiece, or would it flounder, much like the team's first crack at Half-Life? No one knew what to expect. The fate of Half-Life 2 hung in the balance.

Oh My God (Reprise)

Early March brought an important milestone on the project: the alpha play test. In the fall of 2003, the idea of playing through the entire game from start to finish seemed like an unattainable goal. Now, thanks to months of hard work and perseverance, the Valve team was ready to put all 14 chapters of the game through a rigorous play test. The entire company stopped what it was doing and played for an entire week. Even Gabe's dad, a retired Air Force officer, came in to play the game and provide some feedback.