INTRO:

Ever since A.I. War, Arcen Games has tried to design games with different forms of gameplay. They were met with mixed reception, such as the interesting but ultimately repetitive first Valley Without Wind. Eventually, Arcen Games decided to focus on the gameplay elements that it does best, and these can be practically described with just a phrase: “opportunity costs”.

Bionic Dues is another title from Arcen Games that follows in the footsteps of its spiritual predecessors that is A.I. War and Valley Without Wind 2. Like in these other games, every decision that affects the player’s strategic assets comes with a price, the most pervasive component of which is an enemy that becomes stronger over time.

Other than this familiar design, Bionic Dues is a game that emphasizes tactical acumen in order to overcome stupid but overwhelmingly numerous enemy forces.

Unfortunately, Bionic Dues also has some of the more dubious idiosyncrasies of its siblings in Arcen Games’ family, and these are practically apparent from the get-go.

PREMISE:

In the far future, humanity has learned to use sentient robots to perform labour. As to be expected of such a set-up, said robots decided to rebel one day and eradicate their creators.

The story focuses on one city that is involved in the war. It so happens that in the opening hours of the conflict, the robots have managed to defeat many of the humans’ defenders, leaving only the player character, a barely tested recruit of an anti-robot military academy. Every day that the player takes to gather the strength needed to fight the robots with, the tougher and stronger they become.

Sadly, it would appear that the story would be used as little more as an excuse for a backstory. A.I. War, Arcen Games’ first title, had done the same, but in practice, it used the story to justify certain sophisticated gameplay elements. Bionic Dues would do nothing of the sort.

In Bionic Dues, it would be hard for the player to believe that the rebelling robots were able to gain the upper hand in the initial days of the war, after having seen how stupid they are. (The descriptions of the robots and their assets even mention that they are stupid.)

If there is element of the story that is believable at the slightest, it is that after having gained so much of an advantage, the robots have decided to sit back and cobble together an attack force to assault the player character’s home base, thus conveniently giving the player 50 days to prepare.

Yet considering that they have practically taken over the city and have multitudes of fighting units, that the thought of using these existing units to wipe out the last bastion of the human resistance did not cross their minds. (Of course, it can be argued that they are stupid, but this goes back to the disbelief that they were able to subjugate much of the city in the first place.)

MUSIC:

The first aspect of the game that would hit the player is the music for the game. After getting to the main menu that has otherwise thematically appropriate visual designs, the player is bombarded with a cheesy song. While the music of this song, composed by Pablo Vega, is otherwise pleasing, the lyrics, vocalized by his wife Hunter Vega, can seem terribly campy.

“The Home That We Once Knew” can seem disappointing, especially if the player has heard the stirring duet that is “To One Who’ll Stand and Fight”, which has been made for the main menu of Valley Without Wind 2.

Among indie circles, Arcen Games is perhaps notorious for recycling many soundtracks that had been used for earlier games for their later ones. Bionic Dues, disappointingly, will not break this dubious tradition.

Although tracks such as the oft-used “Midnight” does not return, tracks such as “Lieutenant Battle” (the first Valley Without Wind) do, albeit remixed. These add to the campiness of the music in Bionic Dues and make them even more of a thematic mismatch.

Most importantly, turning on the music would have the player missing out on the other sound designs of the game, which are far more thematically appropriate.

It would not take long for an annoyed player to disable the music completely.

REGULAR EXOS:

With the music out of the way, the player can focus on the deceptively sophisticated gameplay elements of Bionic Dues.

The robots that the player uses to fight against the rebel robots are called “Exos”, if only to label them differently from the latter, which practically share the same technology. Supposedly, they are called that because they are shells for the pilot’s mind, whereas the pilot’s body is actually elsewhere.

Anyway, there are six Exos that are available for the player’s selection in Bionic Dues. However, only four of these can be chosen for use throughout any one of the player’s campaigns.

Although the game suggests that these cater to the player’s personal playstyles, one of the six is just too useful to be considered from exclusion from the player’s roster of Mechs. The Science Exo, with its innate and considerable reserves of Hacking points (more on these later), is hard to pass up. On the other hand, picking it means that the player is losing out on the firepower that other Exos can offer, because the Science Exo is practically a wimp in terms of weaponry.

The game can be won without the Science Exo, but this is only possible for playstyles that forces a quick but risky show-down with the rebel robots’ main attack force and thus do not need the long-term benefits of the Science Exo.

Like the Science Exo, the Ninja Exo is not very well-armed, though its Welding Laser (which at this time of writing is only unique to itself) does provide it with some tactical advantages. Its main advantage is its large reserves of Stealth points (more on these later too), which allow it to get very close to enemies to perform shenanigans.

The other Exos are mainly intended for combat, but they differ among themselves in roles and effective ranges of engagement.

The Sniper Exo, as its name suggests already, is meant for long-range combat, whereas the Brawler Exo has plenty of short-ranged armaments. Either Exo can be rendered quite difficult to use depending on the map grid that the game procedurally generates (more on this later).

The Assault Exo is for those who cannot make up their minds on what mix of specialized combat-oriented Exos to pick. It has a mixed balance of weaponry to take on all comers, but the Exos with more specialized weaponry excel better in situational scenarios. Considering that the player can only pick four Exos, the Assault Exo is likely to become less lucrative as a player becomes more experienced at the game.

The Siege Exo is the best Exo when it comes to blowing up many rebel robots efficiently. However, the regular version of the Exo has only a rocket launcher to go together with a light machinegun, making it seemingly deficient – at least before it is upgraded (more on upgrades later).

Interestingly, the player is allowed to pick multiple Exos of the same type, if the player is rather fond of that type and has a playstyle that is heavily skewed towards the use of that particular Exo. However, this may cause some complication in knowing which Exo among the Exos of the same type that the player is picking.

(If the player has not disabled tip messages, the game does suggest that a mixed roster of Exos is the wisest choice in general.)

EPIC EXOS:

Not one for subtlety, Bionic Dues uses the label “Epic” for the upgraded versions of the regular Exos. Each Exo can be upgraded if the player can locate what the game calls “Bahamut Upgrade Stations”. After this, the Exo gains statistical increases across the board, and more importantly, obtain new weapons and slots for parts (more on this later).

The Bahamut upgrades are practically a game-changer, because the Epic Exos offer vastly more tactical options.

For example, the once weak Science Exo gains a chaingun, making it very efficient at getting rid of weak cannon-fodder robots.

The Exo that is changed the most is the Siege Exo, which gains two powerful weapons. One of them is practically an upsized version of the Rocket Launcher. The other, the Shadow Torpedo Launcher, practically makes a mockery of lines of sight and cover (more on these later). Such a weapon makes the Siege Exo very difficult to pass up on, though those who pick it would have the urgent objective of finding the Bahamut upgrade that is specific to this Exo.

Perhaps the most disappointing upgrade is that for the Ninja Exo. The Epic version gains only one additional weapon, the Kinetic Burst, which is also used by the Epic Brawler Exo.

Speaking of shared weaponry, certain weapons that are gained from the Bahamut upgrades are shared by multiple types of Exos. The Kinetic Burst has been mentioned as an example. These shared weapons have the consequence of making the Epic Exos less different from each other, which may be counter-productive.

EXO VISUAL DESIGNS:

In terms of visual designs, the Exos are not lookers. From what is practically coloured-in versions of their concept art, they seem to have gangly arms that stick out of the sides of their bulbous bodies. Further bolstering their imagery as lumps of metal with small appendages sticking out of them, these robots (and their rebellious kin) use hover thrusters instead of legs to move about.

To help the player differentiate between them, they have different colour schemes. Although their other artwork suggests other distinguishing features, such as ocular devices for the Science Exo, these features are not discernible through the top-down view that is used for the actual gameplay during missions. Moreover, due to the top-down view, and their general imagery as described earlier, they have terribly similar silhouettes.

Furthermore, certain Exos share rather similar color schemes, such as the Assault Exo having a color scheme that is only a few shades away from that of the Brawler Exo.

The only reliable way to know which Exo is which is to look at the sidebar of icons for their abilities and devices (which will be described later). Even then, this is not a reliable solution when the player picks multiple Exos of the same type.

WEAPONS:

Although the Exos are heavily armed, even in their regular forms, they have limited ammunition reserves to deal with the robots, which outnumber them tremendously. Managing ammunition, reducing overkill and otherwise dealing with the robots as efficiently as possible are important keys to success.

With that said, there may be an issue with the game right at the screen in which the player selects Exos and Pilots. The player can see the general descriptions of the Exos, but cannot see their weapons until he/she actually starts the game.

Once the player starts the game, the player can examine the properties of each weapon via the tooltips that appear when the player hovers the mouse cursor over the graphical presentation of any weapon. Some of the numbers may seem difficult to understand at first, especially the statistic for area of effect (simply called “splash”, appropriately or not).

The player could look up the documentation for the game, but only by either third-party sources or actually playing the game, would the player understand what these vaguely named statistics convey.

To see the range of a weapon with respect to the Exo’s location and its surroundings, the player can hold down a button (“Left-Shift” by default) to obtain a display for this. Unfortunately, this will also reveal the awkwardness of the square-based range system.

The range of the weapon denotes the number of squares on the tile-based map that the weapon can fire over. This means that the range of the weapon is shaped like a diamond, which can seem odd to anyone who has little experience in grid-based strategy games.

Every weapon has base statistics that are more than enough to handle low-level robots at first (more on robot levels later), but to keep it competitive as the robots become tougher, the player must improve it with parts (more on these later). Indeed, the player must keep this in mind throughout a campaign, because taking out robots with just one shot can have tremendously different outcomes than just taking them out with more shots.

Thus, seeking improvements to the Exos’ weapons becomes one of the player’s priorities, which in turn compete with other priorities.

It has to be mentioned here that after the launch of the game, a patch was introduced to bring balance to area-effect weapons. Specifically, this patch reduces the damage done by the weapons the further away a target is from the epicentre of the area-of-effect; the only weapon that had been spared this change is the Volatizer.

Although this change is documented in the notes for the patch, it has not been mentioned in-game. The only indicator that helps a player realize this is that the highlight icons for affected squares become smaller the further away they are from the epicentre.

VISUAL & AURAL DESIGNS OF WEAPONS:

The aforementioned weapons are not modelled on the Exo’s own sprites, or at least not clearly. The on-screen sprite of the Exo during missions also does not show which weapon the player is using. The most reliable way to know this is to glance at the sidebar on the left and see which icon for which weapon is highlighted. Fortunately, this is not so much of an issue because the gameplay does not occur in real-time.

At least the projectiles and other weapon discharges are modelled. However, players that have played A.I. War and its expansions may notice that these are practically taken from those earlier Arcen titles. Even the sound effects have been copied over, albeit they have been mixed around to make this straight transfer less obvious. Still, such recycling of content can seem lazy.

SHIELDS:

Every Exo has a statistic for its durability, which the game officially calls “shields”. However, there are many moments which can confuse the player as to what the “shields” really are.

For example, the descriptions of the parts that go into “shield” slots (more on this later) suggest that these are the field-projection archetypes of fictional shields. Yet, in another example, a certain robot’s remarks suggest that shields are no different from the hulls of robots or Exos.

The nature of “shields” in terms of gameplay is far clearer than their narrative nature. In-game, “shields” are nothing more than hitpoints. When the shields of a robot or Exo drop to zero, it blows up and is taken out of the picture (unless there is something that can return it to play).

Generally, shields go on one-way trips to zero. However, the Exos that are under the player’s control may be able to partially regenerate their shields, if they have the necessary parts to enable this ability. However, regeneration only occurs when the Exos are completely out of combat, i.e. not taking any further damage and not firing weapons.

Nevertheless, shield regeneration can be exploited in some strategies, such as those that involve Overload, which is an ability to sacrifice some shields in order to emit an explosion that inflicts four times the damage on robots that are caught in the blast.

Other than regeneration, the player may be able to find objects in mission areas that restore shields. However, these are very rare.

STEALTH:

All Exos have the ability to go into Stealth mode, which turns them invisible to the robots. This allows the player to move them about without being harassed. However, with the exception of the Ninja Exo, the Exos come out of Stealth immediately after performing any action other than moving around and hacking terminals.

Speaking of actions, the number of Stealth “points” determines the number of actions that an Exo can take before simply running out. Managing Stealth points is important, because going into Stealth mode can help a player extricate an Exo from a terrible situation.

If a player switches to another Exo from an Exo that is already in Stealth mode, that other Exo does not enter Stealth mode. The player can manually activate its Stealth mode within the same turn to protect the other Exo, but this will not prevent robots that have spotted the other Exo from becoming deactivated. This can be a bit annoying, but it is also an understandable limitation that prevents the player from exploiting Stealth.

If there is anything bad about this other satisfactory gameplay element, it is the unsettling warbling noise that accompanies the activation of Stealth mode.

HACKING:

In addition to Stealth points, the Exos have the ability, or at least potential, to break into computer terminals and open locked doors. The Science Exo is by default the only Exo that starts with hacking points.

There are not many things that can be “hacked”. Computer terminals are some of these; they either yield benefits or trouble when they are hacked. As for which terminals yield which effect, these are randomized from session to session. However, once the player has hacked a terminal and figured out what it does, its effect is associated with other terminals that look the same.

For example, if the player had noticed that terminals with yellow markings cause enemies within sensor range to be buffed, he/she would be informed that terminals that have the same appearance but which are encountered later would have the same effect. Therefore, the player is likely to pass over these terminals because they cause trouble, or just shoot them up to get rid of them.

As for locked doors, these indestructible edifices are mainly there to prevent access to goodies, such as loot containers and stations that grant restoration of ammunition and shields. Opening locked doors is not needed to complete a mission with, but if they hide loot containers, the player may want to unlock them to get some long-term edge.

It has to be mentioned here that the costs for hacking is inversely proportional to the number of days remaining; this is not mentioned in-game at all.

PARTS & POWER:

Every weapon on an Exo has slots for hardware to go into. In addition, each Exo has slots for its reactor, propulsion (which generally affects Stealth) and shields.

Epic Exos generally have more slots than their regular counterparts, which give the player a further incentive to go for Bahamut upgrades.

Anyway, parts are loot that the player obtains from undergoing missions, either from looting them off containers or earning them as rewards for keeping the Exos alive (there is no narrative explanation for this).

Parts go into the aforementioned slots, and they are intended to help maintain the competitiveness of the Exos in combat. Indeed, looking for new parts to replace existing ones is an important consideration when picking the next mission. If the player cannot maintain the competitiveness of the Exos, they may be outclassed by the ever-growing robot forces, especially on the higher difficulties.

As the days in the campaign against the robots go by, the parts that the player would gain from looting become more powerful; this is denoted via the “mark” of a part. This certainly helps the player.

Unfortunately, the game does not mention in any way in-game that the potency of the parts is inversely proportional to the number of days remaining, and not the number of days that has gone by; there will be more elaboration on the differences between these later.

Anyway, the more advanced parts also happen to demand more from the Exos that they would be put into. This demand comes in the form of “power”, or more precisely, the capacity to load more parts into an Exo.

The reactor slots of an Exo are mainly there to accommodate parts that increase the power rating of an Exo; propulsion and computer slots may also accommodate such parts. However, parts that generate power also take up space that could have been used for other parts. Yet, if the player cannot juggle the power requirements, the player cannot start missions at all; the game irritably reminds the player that one or more of the Exos have not been properly tuned.

Most of the parts that the player would find are of the basic variety, or the slightly improved variant that grants one more property to a part. However, there are better varieties, specifically three more.

These varieties grant more properties to a part, without increasing its power cost. Increasingly rarer varieties grant more, and they can result in rather peculiar parts, such as a mine-layer mod that grants virus points and hacking points.

AESTHETIC DESIGNS OF PARTS:

Parts are not modelled on the Exos that they go into, though there is the excuse that they are parts after all.

In the loadout screens for the Exos, the parts are represented with various hand-drawn artwork, such as scopes and field emitters.

There is a considerable variety of artwork for parts that go into certain types of slots, but eventually, the observant player will learn to associate specific pieces of artwork with specific benefits that parts can provide. For example, parts with artworks of what appear to be ammunition cases are parts that increase the ammunition capacity of projectile weapons.

The player may even learn to associate rarity with the differences in the details of similar artwork. For example, scopes of basic rarity have only one lens, but rarer scopes have more lenses.

There are more nuances in the artwork, but the abovementioned examples should suffice. These nuances are perhaps more useful than the names of the parts, which are written with mumbo-jumbo that is more at home in a hack-and-slash fantasy RPG than a game like Bionic Dues.

CURRENCY & STORE:

For reasons that the game does not give at all, the robots drop currency that the player automatically picks up when they are destroyed. A handy counter shows how much money the player has accrued in total, including the money that the player already has before starting a mission.

Generally, the tougher and more difficult robots grant more money when they are slain. Other than this, there does not appear to be any more nuance to this gameplay element.

For reasons that the game even considers silly, the currency can be used to purchase parts from merchants that are still in denial that money is quite useless when the robots are threatening every human with extinction.

At least these merchants tend to sell parts of considerable rarity. Indeed, it is important that the player spends money regularly to replace parts of lesser rarity.

However, other than spending money at the store, there does not seem to be any further use for money.

MISSIONS & TIME LIMIT:

As mentioned earlier, the player has only 50 days to accrue the strength to fight the robots or weaken them before the final onslaught. Each day, the player must pick one mission that does either of this.

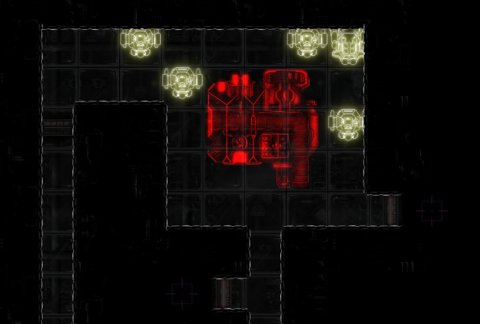

The missions that the player can take are determined by a grid that appears on the map of the city. The player starts with a headquarters building, which is adjacent to a bunch of locations; these locations denote the initial missions that the player can pick from. Completing missions at locations around the map will open up more locations and thus more missions.

If there is any complaint about this system, it is that the city becomes nothing more than a graphical display of the list of missions that the player can possibly take. The locations are randomly determined and distributed when the session is procedurally generated, so they will not depict anything that makes the city more believable, such as districts. This is a lost opportunity to increase the appeal of the narrative of the game beyond it being a mere excuse for backstory.

Anyway, there is a considerable variety of mission types at this time of writing, with more being promised in expansions that may or may not carry a price tag.

On the other hand, an observant player may notice that some of them are little more than chores that require the player to get from point A to point B. This is especially the case for missions which reward the player with parts of better rarity.

Other missions are at least more entertaining. For example, there is the “hostage-rescue” mission in which the player must protect static objects (supposedly cryogenic pods for civilians, who have no understandable reason for being in such a state) from being destroyed (which hardly constitutes the rescuing of hostages). In this mission, the more of these objects that the player can prevent from being destroyed, the more parts that the player can obtain.

Another example of an entertaining mission type has every piece of cover being terrifically explosive. Sometimes, this mission can be an amusingly short cakewalk.

Unfortunately, a few of the most dramatic missions can seem to be too much trouble for the rewards that they provide. For example, there is a mission type that requires the player to run away from a slow but virtually invulnerable robot. The robot prevents the player from exploring the mission area; if the player attempts to do so anyway, the robot will eventually catch up. This can be irksome considering that most other mission types do not have such constraints. The player is rewarded with parts of better rarity, but the player could be better off picking some other mission that provides more opportunities for exploration and planning.

The mission type with the most significant consequences is the one that has the player destroying the robots’ communications assets. Successfully completing such a mission reduces the number of days remaining by five, instead of just one for each mission.

This is a hefty decision to make. Although the robots are deprived of days needed to strengthen themselves with, the player is also deprived of the same number of days to perform missions.

On the other hand, the player is rewarded with parts of the greatest rarity, which cannot be obtained in other ways. More importantly, because the potency of parts is dependent on the number of days remaining and not the number of days that have passed, this can give a wily player an edge.

LOSING A MISSION:

The player can lose a mission by either failing objectives or having all Exos taken out.

If this happens, the player not only wastes a day and forsakes the rewards that could have been obtained from winning the mission, but he/she is also thrown into a mandatory mission where the player must defend the headquarters from a counter-attack by the robots.

In this mission, the player must prevent the headquarters’ (surprisingly many) reactors from being destroyed by the robots, while working on removing them. Each reactor that the robots destroy somehow increases the level of one of the robot types, so this should be clearly something that the player should avoid.

ROBOTS & THEIR STUPIDITY:

The robots, as mentioned earlier, are stupendously stupid. This works in the player’s favour, because the player would find the game terribly difficult otherwise. It is worth noting though that such a design decision makes Bionic Dues very different from A.I. War, Arcen Games’ flagship title.

Anyway, the robots are already seeded into the mission area when a player starts a mission. Their numbers are ultimately finite, perhaps in order to prevent the player from exploiting any infinite spawning.

The robots, even if they are in scenarios in which they are supposed to be on the offensive (such as the aforementioned counter-attack on the player’s headquarters and the final battle), start deactivated. They will only become active if they do spot the player’s Exos, if the player has the Exo whistling to catch their attention (more on this shortly), or if a commotion occurs near them.

Once active, they automatically know where the player’s Exo is, unless it is in Stealth mode. If the player has any sentry turrets or hacked robots, they also know where they are, and will approach to engage.

This behaviour will always play out for any activated robot. This can be exploited, usually by making use of the Exo’s ability to whistle. The whistling range of the Exos depend on their sensor ranges, which means that certain Exos, such as the Science Exo can be useful for luring robots into traps.

If there is any complaint about this otherwise simple behaviour, there does not appear to be a quick way to show the sight distance of the robots. Although there are hotkeys that are already assigned to display the attack range of the robots, there does not appear to be one for showing their sight ranges.

VARIETY OF ROBOTS:

Aside from their common trait of stupidity, the robots are numerous and tremendously varied in capabilities and statistics.

In the first few days of the struggle, the player may come across weak and easily beaten robots, such as the DumBots. Eventually, these get replaced by more powerful enemies such as SkyBots, which can spawn several DumBots. Weaker robots still appear later on, but only as either supportive elements (or at least they are supposed to be) or cannon fodder.

On the lower difficulty settings, the player mostly encounters robots that are not too difficult to deal with. These include the aforementioned DumBots and SkyBots, alongside hilariously clumsy and buggy robots like the BlunderBot (which tends to miss disastrously) and the TigerBot (which is practically stunned every time it is damaged).

However, on higher difficulty settings, the player may encounter more problematic robots more often. These include the PantherBot, which drops mines wherever it moves, and the DoomBot, which become more powerful the more it shoots at things.

Regardless of any difficulty setting, the player will encounter what the game calls “Boss” robots at the final battle, or in assassination missions where the player has the opportunity to destroy them before they can participate in the final battle. As their designation already suggests, these are deadly opponents.

Considering that new encounters can pose a problem to the inexperienced player, it is fortunate that every robot comes with a description that can be seen when the player holds the mouse cursor over them. This description states their most important idiosyncrasies. Clever players will learn to exploit these to defeat them.

AESTHETIC DESIGNS OF ROBOTS:

In contrast with the Exos, the robots had more effort invested into their visual designs in order to differentiate them from each other.

Despite the top-down view of the game, it would not take long for the player to notice that the bulbous-looking robots with goofily large eyes are DumBots and the green stocky ones are TigerBots, among other observations that the player would be able to make.

The robots have two parts to their sprites. Once the robots have been activated, the upper parts of their sprites happen to be turned towards the player’s Exo – even if their harmful attention is directed at something else. This visual design is thus not of much practical use.

As for their weapons, like for the Exos, these are not modelled clearly. Fortunately, the game does mention the weapons that they use in their descriptions, and these are apparently similar or exactly the same as those used by the Exos.

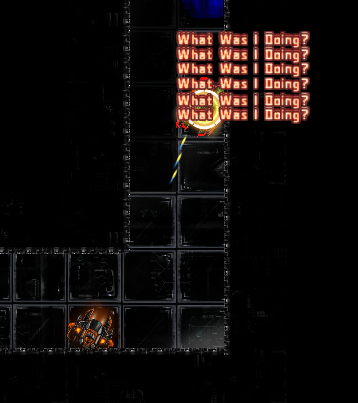

Although different robots certainly look different from one another, they have the same voice, albeit one that has been heavily altered with synthesizing software. They share the same death utterances, and although there are several of these, they are limited enough to the point that they would soon seem repetitive.

Fortunately, different robots with substantially different idiosyncrasies appear to have different lines. For example, the BlunderBot has lines that play out whenever its shots miss (and it misses a lot). The TigerBot with its utterances about memory loss and short attention span is another example.

DIFFICULTY SETTINGS:

Before starting a game session, the player can pick the difficulty setting for it. At this time of writing, the settings mainly affect the strength of the increasing threat posed by the robots. The variety of robots that the player would face has already been described earlier, as an example of the factors that are affected.

Every day, the robots increase their strength by manufacturing more of themselves for the final battle. Their growth rate is proportional to the severity of the difficulty setting. Indeed, at the nastiest difficulty setting, the player could be facing hundreds of robots in the final battle if he/she does not thin out their numbers by performing certain missions.

The robots also gain levels every day. Every level they gain makes them stronger, and in the case of the nastier difficulty settings, also happens to increase their attack range, which can make them a lot more dangerous. The player can force them to regress in levels by doing certain missions, but at the higher difficulty settings, the robots gain so many levels per day that such missions may be a vain effort.

Interestingly, there are no achievements for the toughest difficulty setting, apparently because Arcen Games does not want to subject incorrigible achievement hunters to the severe experience that this setting would provide.

Long-time followers of Arcen Games may notice that Bionic Dues does not offer a versatile tool to customize the difficulty settings to the player’s desire. Perhaps this is a consequence of the game being made for release on Steam first.

VIRUS:

Each of the robots, including the powerful “boss” robots, is vulnerable to electronic subversion. The player can convert robots over to his/her side by expending “Virus” points. The player’s Exos are equipped with Virus points via inserting certain parts into their computer slots; no Exo has Virus points by default, interestingly.

Once the robots have been subverted, they automatically seek out other robots – there is no way to control their behaviour. However, if the robots have abilities that grant buffs, they give these to the player’s Exos. This can be terrifically handy, such as subverting an AmmoBot to have it replenish the ammo reserves of the player’s Exos.

Considering how powerful this ability is, its limitations are understandable. The more powerful a robot is, the more Virus points that are needed to convert them; “Boss” robots in particular are very expensive to convert. The level of the robots and the difficulty setting do not appear to affect the amount of Virus points required, so having more Virus points would be to the player’s increasing advantage.

However, the other major limitation of this tactic prevents the player from abusing it. The player’s Exo can only subvert a robot if it is adjacent to the latter. This means that the player must use this tool in concert with Stealth, or use corners to his/her advantage; these opportunities do not come easily.

MISSION AREA & HAZARDS:

The mission area is one of the most important aspects of the gameplay. Upon starting any mission, the mission area is procedurally generated in order to populate it with enemies, objectives and goodies, among other things.

Any mission area is composed of a grid of squares. Each object, be it a door, an obstacle, a robot or the player’s Exo, generally occupies only one square. The only exceptions are mission objectives, which tend to be large and occupy four or more squares (which make them larger targets if they are search-and-destroy objectives).

As mentioned earlier, weapon ranges are defined with numbers of squares, and these can be seen when there are no obstacles near the player’s Exo.

However, when there are obstacles near the player’s Exo, the player’s line of sight and weapon reach actually follows more believable conventions. For example, that light diffracts around corners is simulated properly in the game, and direct-fire weapons cannot fire around corners. Such stringent designs seem to clash with the designs for the square-based weapon ranges.

(At least the limitations that cover pieces place on weapon range also applies on the robots.)

Speaking of obstacles, these include the map area’s indestructible borders. Although neither Exos or robots can circumvent the borders without the use of teleporters (which only appear in the player’s HQ), there is a bug concerning weapons with area-of-effect properties that will be described later.

Other obstacles include cover pieces. There may be several variations of cover pieces, but the differences are merely cosmetic; all of them still perform the same thing, which is to block the line of sight of the player’s Exos and their line of fire, as well as the robots’ own line of fire.

Oddly, the robots can crash through cover pieces like they are nothing. In contrast, the player’s Exo cannot do the same; the player must shoot at them to destroy them, which may not be a good idea considering that ammunition reserves are limited. Moreover, cover pieces somehow grow in strength as the days go by, which may require the player to expend the ammunition of more powerful weapons.

There are also hazards in mission areas. Some of these cannot be disarmed in any way, such as trip-wires in narrow corridors and which will alert many robots in the vicinity once triggered. These can be very annoying if they happen to be placed where the player must go. They are also difficult to see if the camera is not zoomed in, and there is little other practical reason to do so.

Another hazard that cannot be disarmed is the electric floor, which as mentioned earlier, only appears in assassination missions. These are quite easy to spot though, and can be exploited in many ways, due to a possible bug that will be described later.

After that, there are mines. Most mines that the player would see are those that have been placed into the mission area when it is procedurally generated, but more can be placed by either the player’s Exo or certain robots that drop mines. Either the player’s Exo or the robots can trigger the mines by stepping onto them, regardless of whether they have been placed via procedural generation, by the robots or by the player.

Considering that the “trap skill” of a player’s Exo can greatly increase the damage output of the player’s own mines, stepping onto mines that the player has placed is practically instant death.

It has to be mentioned here that the base damage of mines increases as the days go by; this is not told to the player, but this is an understandable design because it maintains the competitiveness of mines.

What is not understandable though is that mines have hitpoints, and these increase as the days go by too. In fact, in the closing days of the war, mines can be stupendously tough to destroy. It is unsure whether this is a design oversight or not.

Unfortunately, there does not appear to be any way to disarm mines without either triggering them or shooting them. A dedicated method to do so would have been very appreciated.

Next, there are fuel containers that can typically be shot up to release a powerful explosion. Watching enemies saunter near them without realizing the danger can seem like a cliché, but the player would likely appreciate the opportunity to knock out many of them anyway.

It should be noted here that although the Ninja Exo has been stated to be immune to splash damage, it is only immune to damage from exploding fuel containers or booby-trapped computer terminals. The game does not inform the player that it is not immune to splash damage from weapons.

AESTHETIC DESIGNS OF MISSION AREA:

The mission area may have some sophisticated gameplay designs, yet it is also one of the game’s sore points.

Regardless of the mission type that the player has chosen, the textures and sprites that are used for the mission area appear to be randomly picked from the game’s very limited library. Eventually, the player would notice that any mission area does not really look that much different from the rest. The only exception is the mission area for assassination missions, which have clearly hazardous floors, but these exceptions are so rare.

Moreover, regardless of the mission type, the mission area always appear to be indoors, and more often than not, quite claustrophobic. At least the mission area has some ambient noises that are very appropriate for such an appearance, such as ominous machine noises that sound like they are ricocheting down corridors. However, as mentioned earlier, these noises are easily drowned out by the cheesy music.

PLAYER CHARACTERS:

As mentioned earlier, the player character is an untested recruit. However, instead of being one of the most important aspects of the game, the player character is treated in gameplay terms as nothing more than a set of special benefits that alter the gameplay experience of a session. The player character’s narrative aspect is barely any more significant than what has been mentioned earlier.

At least the special benefits that any one of the several player characters are substantial enough to make sessions with different player characters feel different. For example, Genji grants the player the Epic versions of the Exos outright, thus removing the secondary (but important) objectives of finding Bahamut upgrades. Another example is Axle, which is likely the choice of experienced players due to her ability to circumvent the restriction of taking missions that are adjacent to those that have been completed to a limited degree.

BUGS:

Having a hacked Mastermind Bot grant a bonus action on the player’s Exo does not appear to do anything. This may have been deliberate, but if it is so, then the game could have been better off mentioning to the player that this does not work instead of sticking a useless label onto the description of the Exo that has been “buffed”.

Area-effect weapons can somehow affect regions past walls. It is not clear whether this is a deliberate oversight or an unfixed bug (though the former is becoming more likely). Regardless, a wily player can exploit this, which in turn makes certain Exos, such as the Brawler Exo, more useful than they are supposed to be.

Electric floors damage anything that walk over them, this much is apparent. However, they do not continue to apply their damage if what they have damaged earlier simply stands over them. In other words, as long as the player’s Exo can absorb the damage dealt by an electric floor the first time around, it can stay on the floors as long as the player likes.

NO DRM:

In a break from its earlier sale strategies that involved license keys that unlock demo versions of its games, Arcen Games has decided that Bionic Dues is to be solely distributed through Steam. However, instead of shackling the game with scripts that requires the use of the Steamworks API, the game can be played completely without logging onto Steam.

This may go some way to mollify some Arcen fans who had not taken kindly to this change.

CONCLUSION:

Although Bionic Dues serves as proof that Arcen Games still has many ideas for its games that involve interesting A.I. designs, it also shows that Arcen Games has not strengthened its perennial weakness in designing the presentation for their games. It would be very difficult for players to overlook the lack of variety in the game’s visual designs and its wholesale re-use of content from earlier Arcen titles in favour of the better elements of Bionic Dues.

Nevertheless, if the player is looking for tactical gameplay that pits the player against stupid but numerous enemies with varying idiosyncrasies (other than their common idiocy), Bionic Dues is a worthwhile recommendation.