Why I Choose to Kill Goombas

Tom Mc Shea explores how the smallest choices can have the biggest impact on our experiences.

My fiancee does not play video games. Wait, let me amend that. Without a plastic guitar in her hand or high-tech camera tracking her movements, my fiancee does not play video games. But she is an open-minded woman, eager to learn about my favorite pastime, so I've been slowly introducing her to the breadth of what this incredible medium is capable of. Why is this important? Because I realized while we played Thirty Flights of Loving together how the little, seemingly insignificant choices we make during our play time greatly affect how we see the game, and, in some ways, how we view ourselves.

In Thirty Flights of Loving, the basic mechanics are so simple that it feels more like an interactive story than a proper game. One of the only things you can actually do is pick up objects in the environment. Eager to interact with the game the only way she knew how, my fiancee stashed away every object that wasn't bolted down. She scooped up stray bottles, loose bullets, and random guns whenever she found a new cache. After a few minutes of this, she admitted, "I wish I didn't have to pick all this stuff up." Like so many of us, she didn't even realize that she was making a decision every time the E prompt appeared onscreen and that her choice was shaping how she viewed the world. The protagonist transformed from a thoughtful bank robber to a kleptomaniac who couldn't keep his sticky hands in his pockets.

Normally, when we think about moral choice in video games, we imagine the dialogue trees that populate role-playing games from developers such as BioWare. And though this obvious way that we affect the outcome of events is certainly important, its inherent limitations are impossible to ignore. Video games are, after all, about the act of playing, so making important decisions away from the core gameplay feels as if we're reading a "choose your own adventure" book in between bouts of unabashed carnage.

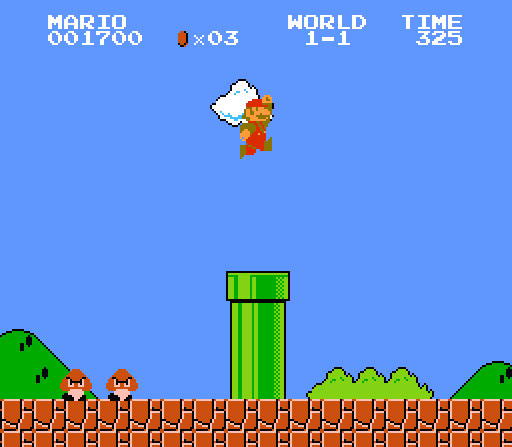

What's so interesting about games is that seemingly innocuous situations continually arise without trumpets blaring in our ears to herald the approach of a poignant decision. It takes no more than a second before Super Mario Bros. presents a situation in which the fate of an innocent life is thrust into the hands of a pasta-filled plumber. We know this scene incredibly well. Mario walks forward a few steps, a slow-moving goomba lumbers onto the screen, and we react instinctively. Do we leap over the mild-mannered beast, collecting coins and bashing bricks as we hurtle toward the exit? Or do we rise above the meager threat, casting down a shadow that momentarily blots out the sun, before we squish the poor goomba flat?

From a game design standpoint, this tableau teaches us how to play one of the first platformers ever created. Run forward without tapping any of the buttons, and you meet your untimely end to the lowly enemy inching toward you. On your second life, you learn to jump over danger, and that simple lesson carries forth for the remainder of the game, telling you how to avoid every obstacle you confront on your way to rescuing Princess Toadstool. But while the design philosophy is readily apparent, the moral quandary is anything but.

Why did I turn Mario into a mouth-foaming, snarling hellbeast of a man instead of the loving plumber that Nintendo presented?

Confession: I always jumped on the goombas. Even though I often had to go out of my way to kill them, and put myself in unnecessary danger as a result, I rarely left enemies alone to live out their days unmolested in the Mushroom Kingdom. For years, I ruthlessly eliminated every crawling thing without questioning what compelled me to do so. There's no tangible reward for felling foes in Super Mario Bros., so why did I turn Mario into a mouth-foaming, snarling hellbeast of a man instead of the loving plumber that Nintendo presented?

The answer is rooted deep within my own psyche. In my day-to-day life, I rarely leave a task unfinished before moving on to my next to-do. And because it would be humiliating and disgraceful to spare a goomba only to have it walk into my backside while contemplating my next leap across a bottomless pit, I had no choice but to kill the darn things before they became a problem. Furthermore, my compulsive need to be right means I often put myself in bad situations when simply accepting another's viewpoint would suffice. Needless to say, the goombas and I disagreed about their place in the world. My innate disposition determined how I interacted with Super Mario Bros., and that scene has been emblematic of how I've played games for my entire life.

Grand Theft Auto relishes moment-to-moment decision making. Fearmongers warn frightened parents that you can murder prostitutes and run down innocent citizens. And though that's certainly true, what they usually ignore is that the choice to commit such atrocities is yours. The beauty of Grand Theft Auto is that it neither condones nor demands such reckless bloodshed. Commit a felony in broad daylight, and the police are on your tail in a flash, which shows that consequences exist even in games that allow you to act out with more violence than you would ever consider in your everyday life.

But what's most fascinating to me is how my interaction with the franchise has evolved as time has gone by. When Grand Theft Auto III appeared, I reveled in unprovoked carnage. No innocent life was worth sparing, and I spent hours ignoring the storyline so I could bring my wrath to the ignorant masses. I don't want to speak for everyone, but I can explain why I murdered so freely in the safe confines of this digital world. I was no stranger to the occasional dark fantasy, and Grand Theft Auto gave me an avenue to pursue these base desires without any lasting harm.

But all of that changed when Grand Theft Auto IV came out. Its predecessors were so cartoonish, so over-the-top, that even though I was stealing cars and running down people, it felt so disconnected from my own reality that I could convince myself that it was merely video game tomfoolery. But the realistic atmosphere in Grand Theft Auto IV gave me pause. The streets, buildings, cars, and pedestrians were plucked from a city I could seemingly fly to if I wanted, so committing the acts of an insane man made my stomach churn. No longer a freewheeling miscreant willing to kill anyone to fulfill an unholy power fantasy, I obeyed traffic laws and avoided unnecessary bloodshed because anything else made me feel bad about my actions.

There are countless examples of these moral choices. In Okami, did you feed the animals or let them starve? And how does that compare to how you treated beggars in Assassin's Creed? Did you rush to aid your struggling partner in Journey? Or leave your partner behind? These moments have no tangible impact on the games as a whole, but that doesn't matter. It changes how we view these games, and once our instincts are laid bare by these choices, it can reveal a lot about who we are as people. Often more than we'd like to admit.

'Got a news tip or want to contact us directly? Email news@gamespot.com

Join the conversation