The Traditional Console Life Cycle is Dying

Prepare for a faster console cadence.

For the last several years, the consoles have been moving toward a tipping point. Now with all the major console players on the same platform as the PC, I believe a paradigm shift has occurred that will end the traditional five-to-seven-year console life cycle. In its place will be a quicker console cadence, one inspired by the iterative nature of the PC and smartphone markets.

"The consumer is attuned to a different cadence of innovation in technology, thanks in great part for the upgrades cadence on mobile phones or PCs," Sony Interactive Entertainment president and group CEO Andrew House told the Financial Times back in June while talking about the company’s upcoming console (codenamed Neo).

Microsoft not only echoed these sentiments, but also added to them, with company engineer Mike Ybarra telling The Guardian, “In the phone market, people are more used to upgrading fast and wanting the latest of everything… With phones, your new apps had better work on that phone and the next one. According to what they're telling us, the consumer expectation is: games and apps had better work, even if I upgrade.” Speaking about Microsoft’s upcoming Project Scorpio console, Ybarra added, “We're looking at the console business and asking, ‘How do we provide that choice to users?’ It resonates with them because other devices are doing that.”

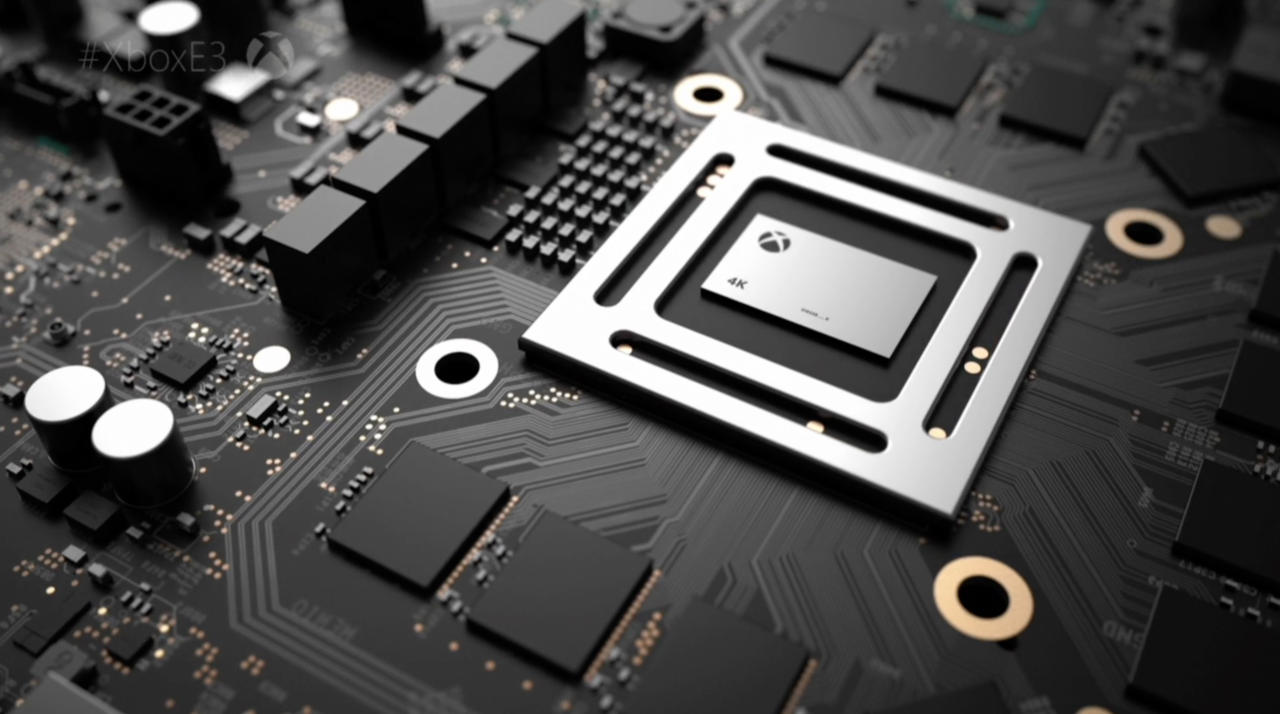

Microsoft’s upcoming Xbox One S, which will support HDR and 4K video streaming, is the first step toward a more iterative road map, but it’s Project Scorpio and perhaps Neo that will be the first major milestones in a new evolutionary process. With Sony and Microsoft’s new consoles rumored to come out next year, this would represent a short four-year gap between console cycles. Unlike the previous console generations, Microsoft says it isn’t abandoning the Xbox One and says that Project Scorpio will not supplant the Xbox One like the Xbox One supplanted the Xbox 360; rather, the company is asserting that both consoles will live alongside each other.

"Compatibility has always been the thing that makes console generations define themselves: when you leave one and [go] to the next, you give up your games, you usually give up the hardware or throw it in a closet--that's what we want to remove," Ybarra told The Guardian.

Microsoft stated that you’ll see the same games work across its different Xbox ecosystems moving forward, “We announced three platforms--today's Xbox One, Xbox One S, and Scorpio. We're giving gamers the choice to say, 'I want to invest in these particular games and this particular hardware, and I want those to work going forward, I don't want to have to worry about giving that up,” Ybarra said. With Project Scorpio offering higher-fidelity graphics able to render native 4K experiences, this relationship sounds analogous to how low-budget gaming PCs and high-end gaming rigs are able to play the same games, just with different graphical settings.

Sony’s stance on its upcoming Neo console, which the company itself is referring to as a more “high-end PS4,” parallels Microsoft’s philosophy, with House telling the Financial Times that Neo “is intended to sit alongside and complement the standard PS4," adding that “we will be selling both [versions] through the life cycle" and mentioning that “all games will support the standard PS4.”

But with both the Xbox One and PlayStation 4 struggling to be backward compatible with their predecessorial consoles (the Xbox 360 and PS3, respectively), oftentimes requiring emulation or manually recompiling games, how can Sony and Microsoft reliably make backward-compatibility promises moving forward?

The seed to make all this possible was planted when Microsoft and Sony both decided to go with x86 processors for their Xbox One and PlayStation 4 consoles. What’s x86? It’s the instruction set that personal computers have been using for years. As a matter of fact, PCs have been building off this old CPU architecture since Intel released its 8086 processor in 1978. As a result, the architecture’s greatest assets include scalability and legacy support. That means x86 has an extremely backward-compatible ecosystem, and it’s what allows you to install a PC game from 1996 to a computer built in 2016. It’s also what will allow Microsoft’s Project Scorpio to be backward-compatible with the Xbox One.

| Console | CPU Architecture/Instruction Set | Date Released |

|---|---|---|

| Sony PlayStation | MIPS | September 1995 |

| Nintendo 64 | MIPS III | September 1996 |

| Sega Dreamcast | RISC | September 1999 |

| Sony PlayStation 2 | MIPS III/MIPS IV | October 2000 |

| Microsoft Xbox | x86 | November 2001 |

| Nintendo GameCube | Power Architecture | November 2001 |

| Microsoft Xbox 360 | Power Architecture | November 2005 |

| Sony PlayStation 3 | Cell/Power Architecture | November 2006 |

| Nintendo Wii | Power Architecture | November 2006 |

| Nintendo Wii U | Power Architecture | November 2012 |

| Sony PlayStation 4 | x86 | November 2013 |

| Microsoft Xbox One | x86 | November 2013 |

| Nintendo NX | TBD | TBD 2017 |

| Sony PlayStation 4.5/Neo | x86 | TBD 2017 |

| Microsoft Project Scorpio | x86 | TBD 2017 |

Above is a list of major console releases and their CPU types starting from the 3D era. You might notice a trend moving toward the x86 architecture.

Contrast this to Sony’s PlayStation 3. Initially released in 2006, the PS3 used a vastly different, highly customized CPU with very specialized cores designed to handle specific tasks. Meanwhile, the typical x86-based CPU features more generalized, multipurpose cores. Named Cell, Sony’s CPU isn’t backward-compatible with Sony’s PlayStation 2, which used its own proprietary “Emotion Engine” processor. While the PS3 was backward-compatible with PS1 games, it relied on the PS3’s superior hardware to combat the extra computing overhead introduced when trying to emulate PS1 games--and even then, not all PS1 games worked. While the launch PlayStation 3 consoles were backwards compatible with PlayStation 2 games, that was because early PS3s had secondary Emotion Engine chips built inside for the sole purpose of backward compatibility. Early in the PS3’s life cycle, Sony decided this wasn’t cost efficient and removed this feature in subsequent models.

Prior to the release of the Xbox One and PlayStation 4, consoles predominately used heavily custom processors built around either IBM’s Power Architecture or RISC instruction set. These highly customized chips provided console manufacturers a high degree of low-level control, which is good if you want to squeeze every bit of performance out of a system with specs that you can't upgrade (i.e., a console). However, their foreign nature often presented developers with a steep learning curve. That’s why games toward the beginning of a console’s life cycle tend to look worse than games at the end of it.

The aforementioned PS3 was, in many ways, a poster console for this issue. Frostbite Engine technical director Stefan Boberg went so far as to tweet in 2015, “I'm pretty sure the Cell retarded the industry significantly. Complexity in all the wrong places.” Polyphony Digital CEO Kazunori Yamauchi, who worked on Gran Turismo 6 for the PS3, described the console as a “nightmare” when speaking to IGN and said it was “a very difficult piece of hardware to develop for.” He went on to say that this caused their development team a lot of stress.

With heavily customized hardware posing growing pains for developers, it made more sense for console manufacturers to move to a proven standard to ease development. With the x86 being so capable and familiar to developers, both Sony and Microsoft decided to jump on that architectural bandwagon.

Getting on the x86 standard also allowed third-party engines like Epic’s Unreal Engine, Valve’s Source Engine, and Crytek’s CryEngine to more easily be commoditized. This further lightened the resource load on game developers. From their inception, these engines have been designed to run on the wide array of PCs out on the market, which makes them inherently scalable across hardware. Epic Games CEO Tim Sweeney recently told me that Unreal Engine 4 has “no trouble” scaling up from a 1.8 teraflop system to 9 teraflops or more.

In the ’90s and early 2000s, it was rare to see console-game developers share engines. As a matter of fact, many console game developers often had to spend far too many of their resources building their own game engines from scratch. While building your own game engine can potentially allow you to squeeze more performance out of your creations (Naughty Dog’s Uncharted Engine is a great example), modern consoles are largely powerful enough to muster playable performance without an unreasonable amount of effort from developers, it doesn’t make sense for most development studies to allocate so much time and money to build their own proprietary engines when so many competent third-party ones are readily available.

Now with Sony and Microsoft both using x86-based CPUs, it makes sense to leverage the architecture’s strength: backward compatibility. This is what allows Project Scorpio to have beefier hardware yet be completely backward-compatible with the Xbox One (without having to rely on software emulation or forcing game developers to recompile code). This highlights the comments that Microsoft’s Phil Spencer made to sister site Giant Bomb, “One thing we should make sure that everyone understands is, every game that comes out in the Xbox One family will run on the original Xbox One, Xbox One S, and Scorpio,” he said. When asked if there would be Scorpio-exclusive games, he added, “No, the line of games you're going to get to play is the same.”

This faster, new console cadence may cause some concern and give the impression that players must upgrade consoles every three to four years moving forward. When I asked Sweeney what he thought about the faster console cadence, he was highly optimistic. “Upgrading consoles midlife is a great step forward for the industry,” he said. “The most difficult part of the entire console industry has always been resetting the user base to zero every seven years or so, whereas if we incrementally upgrade the hardware, then we can bring more performance to gamers without wiping the slate clean. That's incredibly valuable… By doing these incremental updates, the industry can move forward technologically at a much faster pace without those business challenges. I think it's really the ideal model: bringing the best upgradeability of the PC with the reliability of the console kept, so you're never going to have to deal with driver problems on a console, but you will get the newer hardware.”

When I asked Sweeney if he thought that the landscape of consoles had shifted, he agreed. “Yeah, I think this is a fundamental change in the way the console industry operates,” he said. I think it's been a long time coming in recognizing this is possible. You could imagine this approach being extended out in the future once we have 100 million gamers on the current generation of consoles. No console company would desire to start over from scratch but would continue to deliver more and more performance with hardware upgrades every few years.”

Sweeney believes that this new approach is a win-win for both sides, “I think that's an incredibly smart approach,” he said, “both to benefit gamers and to make industry economics more palatable for game developers.”

Those players worried they may have to fork over hundreds of dollars every few short years to get a new console may be relieved to hear Sweeney’s take. “As consoles gain performance, we will be eager to take advantage, and we won't need to leave the earlier console gamers behind,” he said. “We can continue to sustain, continue to run on the current devices for the foreseeable future.”

Clarifying what he meant by “foreseeable future,” Sweeney mentioned that future consoles could potentially be relevant for “a decade or more.” These sentiments coincide with what’s happening on the PC, considering a high-end gaming PC from 10 years ago is still largely able to play most modern games, albeit with fettered graphical features compared to a modern gaming rig.

Sweeney’s also excited to play around with the different graphical bells and whistles the two tiers of consoles will offer, “We can decide exactly what features we can turn on in each of the two cases,” he said, “and really polish the game heavily for both cases and not have to worry about all of these intermediate points.”

While Project Scorpio will support rendering native 4K graphics, Microsoft won’t force all games to run natively at 2160p on the upcoming console. “We never said we’d mandate 4K frame buffer. We won’t,” Microsoft’s Spencer told Giant Bomb at E3 2016. Instead, the Xbox head said that the company is willing to give control over to the developers. “I think creative freedom and how you want to use the power of the box is something that I always support,” he said. “I came from first party...so putting the right tools in the hands of the creators, the best creators, is our job as the platform.”

Considering that today’s consoles are highly influenced by the smartphone industry, which moves at a super-fast cadence, I asked Sweeney if he could envision consoles following suit with bi-annual or even annual revisions in the future. Sweeney doesn’t think that will happen with consoles. “There's a cost and complexity to an upgrade bidding. Upgrading every year...would create so many points that developers would have to consider and support. That would be hard. I think revisiting console tiers every several years, [where] there's potential for significant performance gains, is very interesting.”

While there’s still a lot we don’t know about the upcoming consoles, one consistent narrative seems to be emerging--the death of the traditional console life cycle.

Got a news tip or want to contact us directly? Email news@gamespot.com

Join the conversation