The Suffering: Ties That Bind Designer Diary #3--Changing the Future, Changing the Past

We check out Ties That Bind's unique narrative structure in this developer diary.

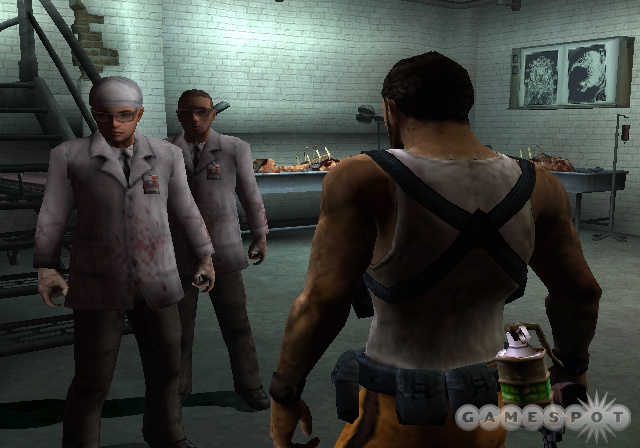

In most gaming storylines, you typically have a limited view of the main character's past history--a past that may or may not affect the actions you control in the game. Often, backstory is meant as a way either to flesh out a character's quirks or, in uglier cases, to simply add a few more dialogue screens to click through. In The Suffering: Ties That Bind, the development team has gone to great lengths to ensure that the game's storyline, which follows the series' tough-guy protagonist Torque through a series of grim adventures, not only lets you know who Torque is but also gives you control over his future--as well as his past. Just how was this unique narrative structure accomplished? In our third designer diary for Ties That Bind, the game's creative director and writer, Richard Rouse III, explains just how they went about it.

Changing the Future, Changing the Past

By Richard Rouse IIIDuring the development of the original The Suffering, I don't believe we fully understood what we were creating. I think this is true for most original games with innovative design elements, but in particular with The Suffering we didn't realize how much people would like our take on interactive narrative. From the very earliest concepts of the game, we wanted to let the player's choices in the game not only determine the ending of the game, which plenty of games had done before us, but also fundamentally change the past of the main character. From the first scene of the game, players knew that Torque's life was haunted by a tragedy (the death of his family), but at the same time players did not know what role Torque played in that grim event. By the end of the game, players have determined Torque's complicity through the moral choices they made over the course of their play experience. Looking back at it now, I can't think of any other story-centric action adventure games that let you determine both your future and your past. I'm very glad that players got as into that as they did, but I certainly wouldn't have predicted it. At the time, we were just going with a design and storytelling idea we thought was compelling. We didn't analyze it; we just went with our gut.

For creating the sequel, we had the advantage of having a better understanding of what we were dealing with from a storytelling standpoint. This meant we were better able to deliver on a lot of the promise of the storytelling in the first game. Writing a story that has both a past and a future that can be altered has its specific challenges, but the extra effort is worth it in the end. As Ties That Bind begins, Torque already knows whether he is guilty of killing his family or not. This is tied to our "multiple beginnings" system that links to the end of the first game. But there's still a lot the player does not know, particularly the reasons for Torque's actions.

For the evil beginning, players still don't know what drove Torque to kill his family in cold blood. For the medium beginning, players have little insight into what drove Torque's boy, Cory, to behave so monstrously. For the good beginning, players have no idea who "the Colonel" is or why he sought revenge on Torque. And for each different beginning to Ties That Bind, there are multiple endings, each based on how players play this game. This creates a total of six different ways Torque's past can be revealed.

Once we understood that determining your past was a key part of our storytelling appeal, in Ties That Bind we planned the story so we could slowly build up to the central revelation at the end. We laid the groundwork all throughout the story instead of just springing it on the player on the last level, giving Ties That Bind a significantly more compelling narrative than the first game.

Morality Play

There are other aspects of our storytelling we improved on due to our improved understanding of what we were working with. This time around the moral choices the player makes are much more integrated into the story and are evenly distributed over the course of the narrative. Our goal was to make sure these choices never seemed out of place or "gamey," and I think we succeeded.

We also went out of our way to make sure the multiple story paths were truly different over the course of the game. We realized if we were going to go to all the effort of having the morality system and the multiple-ending/multiple-beginning story, it was not that much more work to make sure players understood their status over the course of the game. So you'll get different characters showing up in the game at different junctures, including one level with completely different companions based on your path. In one case, you'll also engage in one of two unique boss battles. And, as I discussed in my first designer diary, you'll have the significantly different versions of Torque's creature form. In short, the consequences of your actions are much more apparent throughout the game.

One of the biggest challenges with telling a story in a game is the conflicting agendas of traditional narrative and the open-endedness implicit in interactivity. For example, in action adventure games, players want to feel that they are in control of the fate of their player character and his story. Furthermore, the game will become more immersive if players feel that, at least for the duration of the game, they become that main character. This is somewhat at odds with traditional storytelling, which almost always involves a strong, well-defined main character who has a very specific dramatic arc.

Over the years, many talented designers have opted to embrace the traditional narrative by having well-defined main characters that the player controls but never really becomes, whether it's Manny Calavera in Grim Fandango or Solid Snake in Metal Gear Solid. On the opposite end of the spectrum, some designers have opted to keep the main character much more undefined, such as Half-Life's Gordon Freeman or Grand Theft Auto III's mute protagonist. These characters didn't speak, and they had relatively undefined backstories; as a result, the conflict of the story had to be crafted without involving them or, if it did, without ever getting too specific.

With the Suffering series and the player's control over the narrative, we are fortunate enough to have both a main character with a distinct past and someone players feel they can become. Torque, who is almost entirely mute for both games, is haunted by his role in the death of his family, which makes for great drama and conflict. But we don't have the problem of distancing the player from the character, since, as I've discussed, the nature of that dark act is determined by the player's actions. Players can't say, "But I never would have killed my family," because we can point to their actions in the game and show them that's exactly the kind of person they are. Or at least that's how they were when they were playing the game.

Compared to the lofty ambitions of true interactive storytelling, I certainly acknowledge that The Suffering is just a first step. Games as a medium have a long way to go before players have true total control and authorship over the narrative of a game. But I like to think that The Suffering has made some contribution to opening up the possibilities and showing just how compelling they can be.

Got a news tip or want to contact us directly? Email news@gamespot.com

Join the conversation