Power to the People: The Text Adventures of Twine

Carolyn Petit considers the importance of a new tool that makes it possible for almost anyone to create a game.

Stealthy assassins. Dashing adventurers. Gun-toting soldiers and space marines. You see these types of protagonists surface again and again in mainstream games, and as the process of producing games becomes more and more costly, the games that feature heroes like these take fewer and fewer risks and become increasingly predictable. Developers rely on what they know works in order to increase the likelihood of financial success, and graphic violence is becoming more common as it gives games a way to surprise and excite players, since the formulaic gameplay and familiar subject matter aren't likely to.

Meanwhile, far from the games designed by committees at mega-developers, all the way at the other end of the game creation spectrum, a new tool has emerged that empowers just about anyone to create a game. It's called Twine. It's extremely easy to use, and it has already given rise to a lively and diverse development scene.

It was a tweet by game designer Anna Anthropy, a vocal champion of Twine, that first made me take notice. Referring to Memorial by Travis Megill, she wrote, "we live in a world now where someone can make a videogame as a memorial to a sibling. let that shake you to your core pls." It worked on me.

…it's no surprise that so many people look at games and think, "They have nothing to offer me."No programming knowledge is needed to use Twine. It allows you to link passages of text via links, which has led many people to compare games made with Twine to old Choose Your Own Adventure books. But Twine allows you to do things that those books never could. Games can keep track of decisions made and actions taken by players much earlier in the game--what type of weapon they selected, for instance, or whether or not they collected a particular key. With a bit of creativity on the part of the creator, games can have puzzles that players can't quickly "solve" by just trying each of a few options. Games can also include images and videos, and with a bit of extra know-how, you can also employ basic effects, such as flashing text, which can do a good deal to foster a particular mood in your game.

There's some debate about whether or not Twine games are actually games, and whether such games have any value. My feeling is that not everything created with Twine is a game. Some things, like Travis Megill's Vacuum, an intimate tale about a mother's love for her schizophrenic son, are more like stories in which you're an active observer rather than a participant. You have no impact on the events, but you can move among them to some extent, perhaps choosing to examine an environmental detail or to follow a character's train of thought as she's flooded with memories. It's not a game, exactly, but there's still enough participation on your part to make the experience feel different from that of reading a book.

Other experiences created with Twine are definitely games, in my opinion. A great example of Twine's potential for games is Beginning, a fantasy adventure by the writer known as WelshPixie. Here, you are an active participant. You name your character and make decisions that affect the course of the story. It has a few visual touches--a portrait of a character you interact with, and a map of the area--but these aren't what makes Beginning a game, nor does their absence from other Twine projects prevent them from being games. The Infocom text adventures of the '70s and '80s, such as Zork and Planetfall, were certainly games. And clicking on text is as legitimate a way of participating in a game as anything else; after all, that's the primary way you perform actions in Maniac Mansion, and that's definitely a game.

Of course, no Twine game is going to be the next Call of Duty. So what? No independently printed short story is going to be the next New York Times best-seller. No indie film made on a shoestring budget is going to be the next box-office smash. That doesn't diminish the importance of those works. They assert that literature and film are not just the realms of the privileged few who have the backing of big studios and publishers. True, Twine only allows people to create text-based games. But there's tremendous freedom in that. There are no limits to setting or subject matter. You'll probably never see a big-budget, mainstream game designed to speak primarily to young people contemplating suicide, or to people struggling with drug addiction. But Twine games can be about and for any group of people, however big or small. And of course, Twine games can also be about fighting interstellar wars, surviving on dinosaur-infested islands, and pulling off missions as a superspy. There are no limits.

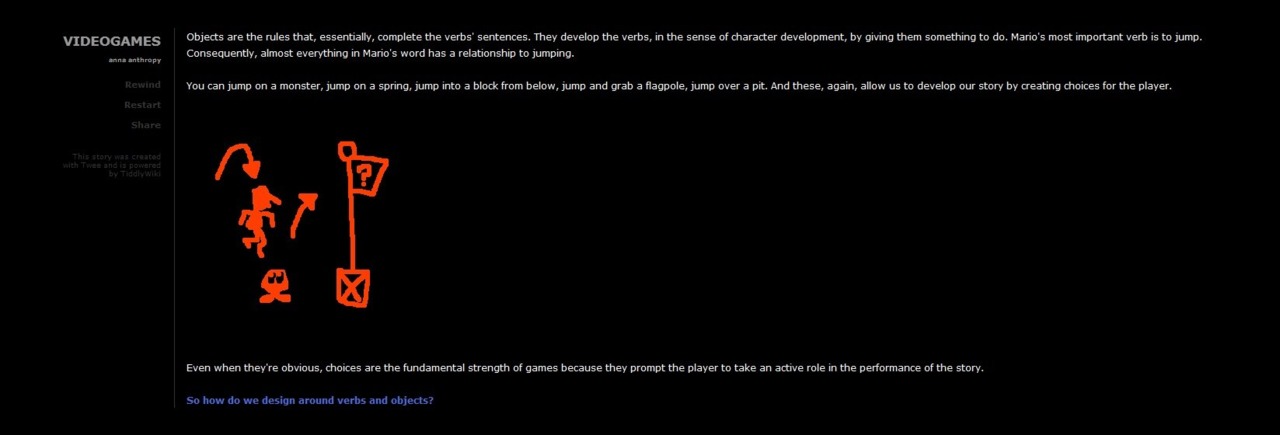

Of course, no Twine game is going to be the next Call of Duty. So what?Naturally, a large number of people will have no interest in any games made with Twine. But graphics aren't inherently better than text, any more than movies are inherently better than books. They're just different. I've already played Twine games with beautiful language that put me in the hearts and minds of their characters in ways that cutscenes in games rarely do. I've played Twine games that have made me feel dread, horror, and excitement. If people keep experimenting with Twine, and get better at taking Anna Anthropy's advice about designing around verbs and objects to make players feel like empowered participants in the story, I think we could see some great things come out of this scene.

I can't help but hope that Twine is just an early example of what will become a variety of production tools that empower individuals who don't have the money to finance game production or the financial backing of game publishers. I've long felt that games are for everyone, not just the stereotypical young male "gamer." But with so many games rehashing the same well-covered territory populated by assassins and space marines, it's no surprise that so many people look at games and think, "They have nothing to offer me." As mainstream games become more and more homogenous, a diverse array of creators taking some ownership of the medium, even if it's at the fringes, can and should shake things up, making it so that games are not just by and for the few. When games are by the people--by women and gay people and poor people and the culturally marginalized and kids growing up in Iran and not just primarily by the people who are paid to make them by companies selling products designed to appeal to as many customers as possible--they will inevitably be for the people, too. Twine is a small but important step in this direction.

'Got a news tip or want to contact us directly? Email news@gamespot.com

Join the conversation