Dev's Controversial "Wage-Slave" Remarks Sparks Discussion Over Games Industry Crunch

Hear what those in the games business have to say about crunching to get a game done.

Developer Alex St. John recently shared some controversial thoughts regarding working conditions in the video game industry, sparking a heated discussion over the attitude some have on the subject and prompting a hard-hitting response from his own daughter.

The situation began with a VentureBeat interview with International Games Developer Association executive director Kate Edwards on the subject of crunch time. This is likely a subject many video game fans are unaware of, save for those who follow the industry closely. Developers are routinely subjected to "crunching" on a game. This is the period where, as a game's release approaches, developers are expected to spend extremely long hours working to get it done. This isn't a situation where these developers are asked to spend some late nights at the office for a week or two; crunch can last for months and, in extreme cases, even years. All of this extra work can go uncompensated, and sometimes comes at the cost of developers' relationships and health, both physical and mental.

Suffice it to say it continues to be a serious issue for the industry, even as the IGDA, a non-profit advocacy group for game developers, shows things have been improving over time. Edwards and the IGDA have plans to help this trend to continue, in part by drawing attention to companies that do and do not handle it well.

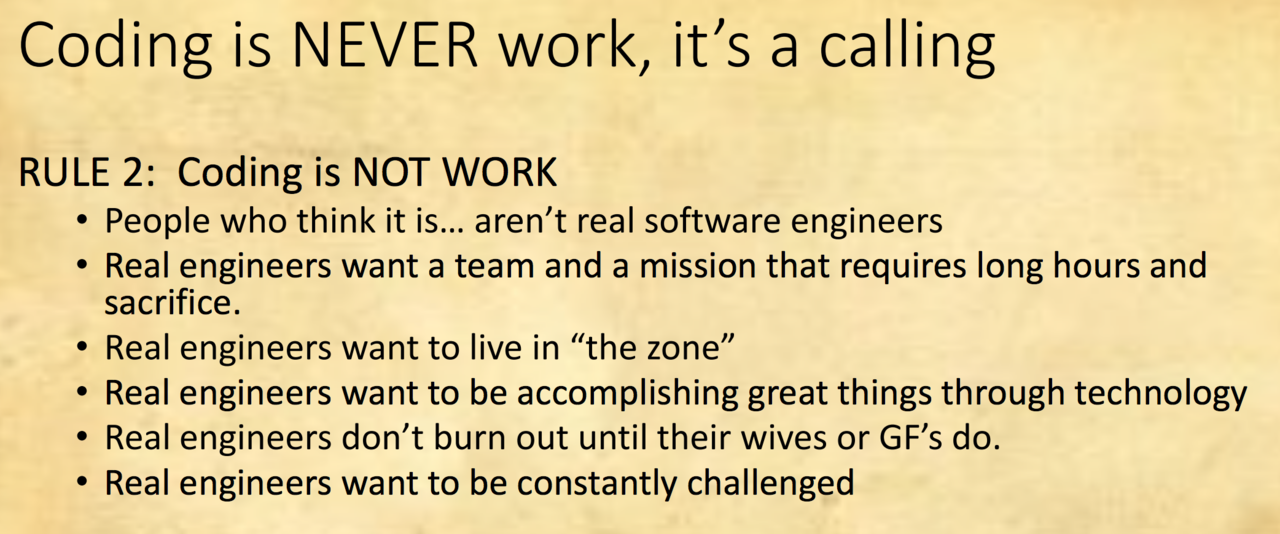

The interview prompted a response from St. John--a longtime member of the industry, one of the creators of Microsoft's DirectX, and the founder of game network WildTangent--in the form of an editorial also published on VentureBeat. In it, he dismisses concerns over crunch, deeming those concerned with fair wages and working conditions as having a "wage-slave attitude."

St. John's piece goes on to ridicule basically any developer or aspiring developer who isn't overly enthusiastic about working 80-hour weeks without being appropriately compensated.

"Don't be in the game industry if you can't love all 80 hours/week of it--you're taking a job from somebody who would really value it," he concludes.

All of this prompted something of an outcry from many in the industry. This, in turn, led to him posting several follow-ups on his website, two of which are downright bizarre and continue his dismissive attitude, while a third expands on the recruiting presentation.

Most incredible among the many responses St. John's piece prompted was one from his 22-year-old daughter, Amilia St. John, who uses terms like "horrific toddler meltdown," "toxic waste trash fire," and "written hemorrhoid" to describe parts of her father's article. She also relays her experiences as a woman in the technology business, as her father also presented some views she deemed troubling regarding the roles of women in the industry.

She ends her response by pleading with her father to stop: "And it is from here that I beg my father, for the love of his daughters, to stop hindering our progress as women in the industry and start using his influence to promote positive experiences for minorities in tech."

To gain some further insight into the realities of crunch in the industry, GameSpot spoke with the IGDA's Kate Edwards about the subject and St. John's comments.

"My first impressions are that despite this individual's legacy in the game industry, he's someone who's grown woefully out of touch with the modern game development process and doesn't seem to recognize the need for the game industry to mature its work practices," she said when asked for her initial reaction to St. John's piece.

But his viewpoints aren't widely shared in the industry, at least anymore, according to Edwards.

"The opinions of St. John are definitely in the small minority in today's game industry, as evidenced by many ongoing, anecdotal conversations with developers worldwide as well as opinions expressed via the IGDA's Developer Satisfaction Survey," she said. "Over half of respondents (52%) did not agree with the notion that crunch is a necessity and over half (53%) attribute poor/unrealistic scheduling as a top reason why crunch occurs.

"There are companies that somewhat maintain crunch as a virtue, or rather an 'unfortunate necessity,' but there are many examples of companies which are successful and rarely crunch. My assertion is that it's more about performing an honest revamp of management and scheduling practices in our industry and stop pushing it off as something to deal with in the future."

Crunching isn't something exclusive to the games industry (which is largely not unionized), and Edwards notes it's "common in many creative media, including games, film, television, literature, and so on. Part of the inherent nature of creative works is that they're never really finished--they only reach a point of sufficient release, usually tied to a specific date that dictates all the related machinery around the content's launch (e.g., marketing campaigns). In some cases, the creative vision gets extended--such as director's cuts of films or downloadable content in games."

Edwards argues what's key when considering crunch is that companies are upfront with prospective employees about how often it occurs, give their workers an option to work long hours, and pay them for doing so.

"Condoning unrelenting, ongoing, uncompensated crunch as some form of positive value for the game industry is an antiquated notion" - Kate Edwards

But comments like St. John's present a problem in that they have the potential to scare away talented individuals. Edwards hopes that by talking about crunch, it can help to continue improving when and how it happens.

"Condoning unrelenting, ongoing, uncompensated crunch as some form of positive value for the game industry is an antiquated notion and I do think it continues to harm the game industry's image and its ability to attract top talent (who now have many other tech-oriented options to choose from). My hope is that by highlighting this issue, we will see more companies rethink their approach to crunching and realize the importance of valuing the people who work for them as creative professionals and human beings and not just easily-replaceable cogs in a machine."

Asked what she would say to an aspiring developer who was disheartened with St. John's message, Edwards said, "The majority of the companies in the game industry are aware of the need for better work-life balance and better management of the factors that are conducive to creating extended crunch periods. That being said, the industry has a long way to go to make sustained crunch more of an anomaly than a norm.

"Ultimately each individual needs to assess the degree to which they're willing to sacrifice their time, energy, and health and ask blunt questions to companies about their working conditions and crunch hours. The more people continue to raise the issue, the more companies will realize it could be a factor affecting the attraction of talent."

Most recently, St. John posted a sort of recap to the response, in which he attempts to clarify that his target wasn't what he calls "real victims," but he was trying to tell "a bunch of adult professional game developers that they are NOT VICTIMS and to stop pretending they are." He also describes an offensive recruiting presentation (PDF) on his website as "tongue-in-cheek." He later claims that unpaid overtime doesn't exist in the games industry, and says he plans to "attempt to write some constructive articles on work-ethic, burn-out, and time management for the few among them who might actually like to escape their wage-slave misery."

Other developers have recently spoken out about crunch in the industry, and about St. John's piece specifically. We've gathered up a few of these individuals' thoughts, both those posted online and those shared directly with GameSpot, below.

Rami Ismail (Vlambeer) initially tweeted about St. John's article, calling it "absurd," suggesting developers can legitimately burn out, and condemning the idea that those who want reasonable hours lack passion for games. He then went on to author an inline response that addresses St. John's piece point by point.

"Devs, this is an absurd article," he concluded. "I care so much about games. I've dedicated my life so far to making games, to enabling others around the world to make games and to learn as much as possible about this medium--mobile, casual, AAA, indie, whatever. I tell you here and now: structural crunch is bad, and burning out is real. I hope you'll take care of yourself, so we can have you and your games and your experience around in this industry for many more years to come.

"Whether it's as a 9-to-5 employee making AAA games, a legendary developer, an indie working on their first games, or a part-time developer that makes games for fun. Be passionate. Make games. But please take care of you."

Kepa Auwae (RocketCat Games) shared some thoughts with GameSpot: "I end up not talking about crunch much because I willingly subject myself and sometimes others to it. I'm an independent developer, so the reason for crunch is usually personal survival. I'm not an executive of a AAA company making 200 people work 16-hour days and then firing them, but that doesn't mean what I'm doing isn't crunch. I feel hypocritical talking about it.

"Forcing AAA developers to crunch is a symptom of a greater problem: the big companies know they can treat their employees like s***. They know they can just fire employees and replace them with younger, more eager employees. And when those younger employees grow old and gain families and expenses and a sense of dignity, they too can be fired and replaced with younger, more eager employees. It's one of those well-documented 'we know we can treat our employees like s***' jobs, similar to working at Walmart.

"There's a huge story on game dev labor exploitation what, every quarter? More? Crunch, faking failed deadlines to force worse contracts, mass firings. Empty rooms that exist to put teams in until they quit from boredom. I'm forgetting which company does what, the stories blend together. [Ed. note: The New York Times reported on Sony doing this in Japan in 2013.]

"You could go indie instead. Alex St. John's article actually mentions this as part of his 'don't like it, leave it' premise! Problem is, you're likely still going to crunch working for your own projects. Maybe you can work on your first project and complete it super fast with minimal effort. Then it becomes a viral hit that makes millions of dollars. It could happen! Of course, you could also save even more time by just spending your entire life savings on lottery tickets. Same principle.

"Alex St. John's article also recommends quitting and going into another tech field. This seems pretty reasonable, actually. Seems a lot more stable. That or taking contract work, since it puts the risk on the person paying. This is once again the 'don't like it, leave it' premise and people didn't seem real happy about the suggestion."

Alexis Kennedy (Failbetter) spoke about crunch at the Game Developers Conference in March, prior to St. John's comments. "Some of you have no choice but to crunch. If you have a choice about crunching, crunch is bulls***," he said, GamesIndustry.biz reports. "I've only been a game developer seven years, but I've been in tech 20 years. The data are in. It's really clear. If you work overtime for a week or two weeks, you see a boost in productivity. If you work overtime for four weeks, eight weeks, six months, productivity drops."

"Because it is a slippery steep-sided pit," he told the site when asked why crunch is a problem. "People love making games, and games are a very competitive industry, so there's pressure to perform, as there is in many industries. And if you start getting into a hole, the natural thing to do is just to work more hours or to encourage your team to work longer hours. 'We just need to get this one release out the door and we'll be ok. We just need to fix this one bug.' And once you start going there, it starts to be a natural solution, and your ability to look at the bigger picture and your ability to think clearly are both compromised. So the further in the crunch pit you get, the harder it is to get out."

Got a news tip or want to contact us directly? Email news@gamespot.com

Join the conversation