INTRO:

Dice-dependent gameplay has had a long time to evolve. It started as no more sophisticated than the randomized distance of movement that Snakes & Ladders had, but there had been plenty of innovations since. The most interesting one is the storage and allocation of dice with different numbers, which is something that Tharsis highlights.

PREMISE:

For a game that is mainly about tossing dice and deciding what to do with them, Tharsis, apparently, has a story of sorts. There is a space mission to Mars, and like all sci-fi stories about journeys with conventional space travel to somewhere, something would go wrong.

The modular space-ship that the protagonists are on are struck by a meteor that the crew did not see coming (apparently because the two awake crew members were not monitoring the sensors at the time). The remaining four crew members are awakened, and must make do with whatever remains of the ship to reach Mars.

Along the way to Mars, the crew receive video feed from the eponymous Tharsis, a region on Mars. Each portion of the video feed shows something that is unsettlingly familiar. Successive playthroughs and better performance on the part of the player would eventually fill in holes in the story-telling, but the player should not expect any ground-breaking sci-fi story-telling.

WEEKS:

Tharsis is a turn-based game. The progression of turns is represented in numbers of weeks. At the end of each week, bad things happen and the effects of bad things that have yet to be resolved would be experienced. The turn of the week may also yield opportunities to give the crewmembers a second wind, which should hopefully let them fix any extant problems before new ones compound their situation.

CREWMEMBERS:

The crewmembers are the player’s main assets. The player starts with four, and there would be no more. The player can lose them through mishaps both unwitting and unavoidable.

Each one lost can be devastating, and diminishes the player’s chances of success further. There can be something that can be salvaged from such losses, though not without a price.

DICE:

Dice represents the energy levels of the crewmembers. They will always have a minimum of one, but there is little that can be done with just one die.

Dice are rolled whenever a crewmember is deployed to a module. The numbers rolled represent both the effort that the crewmember has produced and also his/her luck. The player allocates any dice that survive the roll, or re-roll them if there are any re-roll attempts left.

After every deployment, the dice rolled are returned to the crewmember, minus one. This loss represents exhaustion and food rationing.

To gain more, the crewmember has to be fed what is presumably additional food. The Captain crewmember can also inspire her colleagues that happen to be in the same module, thus helping them regain one die. There may also be “research” options that increase their pool of dice. There is also the Life Support module, which can restore all of the dice of a crewmember (presumably through accelerated rest or some other sci-fi nonsense).

However, all of these opportunities are rare. The player needs to have the right crewmembers in the right module, deploy consumable resources at the right moment, and most importantly, must have the luck to get specific dice-roll outcomes.

Even if the player is lucky, each crewmember can only have up to six dice. They cannot exert superhuman levels of effort, after all.

HEALTH:

The crewmembers are ultimately mortal, so they can die. However, they also happen to have “video game health”, meaning that as long as they have one health point remaining, they retain full functionality. Indeed, wise players might trade some of their health away in return for other benefits, if they have “spare” health.

Health is not easily regained. There are some crewmembers that can restore health if they get the dice to do so, and the medical module can restore health too, but that would require a let-up in the bad events that would happen. More often than not, health would be regained through “side projects”, but “side projects” are iffy things, as would be explained later.

The health of any crewmember can never go beyond 6 points. However, they can lose maximum health through a gameplay element that will be described later.

FOOD:

Food is practically a dice-refill system. Any unit of food that the player has harvested can be fed to any crewmember at the end of each week to restore some dice. Any excess dice is lost, however, so the player will want to feed crewmembers that have considerably depleted dice.

Like the other resources, food is not easy to come by. Food is mainly produced at the Greenhouse Module, but that requires crewmembers to work the module. Some “side projects” can yield food, but often at the cost of something else. Perhaps the most desirable food acquisition is through the research system, which will be described later.

CANNIBALISM:

The regular food that the astronauts eat is plant-based. They can eat meat too – but the only source of that is each other.

In any regular playthrough, one of the two crewmembers that are already doomed happens to be in the infirmary. She is already dead, having been killed by fast moving debris. The rest of the crew have secured her to one of the beds, not knowing what to do – until a few weeks later. If the player is not fortunate or had been careless, more corpses would be joining hers.

When those few weeks are up, pragmatic desperation would have the crew somehow unanimously deciding that cannibalism is an option. Each corpse yields three rations of meat, which can be fed to crewmembers just like regular food.

The catch here is that each unit of meat only restores two dice, and it reduces their maximum health by one point. It also raises the stress level of that crewmember significantly. There is also the aesthetic change in their dice, all of which become unsettlingly bloody (thus becoming a reminder that this crewmember has eaten some of his/her colleagues).

After eating their already dead crewmembers, any further meat has to be obtained from the other crewmembers. They either have to be killed in accidents, or deliberately killed at the end of the week.

Interestingly, the decision to murder one of the crewmembers to get meat is carried out immediately, without any seeming resistance from the victim. Of course, there is the stress increase from having to kill one of them and the stress increase from eating his/her meat, but there is no other consequence.

STRESS & SIDE PROJECTS:

Speaking of stress, the crewmembers are still people, and people can be pressured. Obviously, being in a space-ship that is constantly hammered by bad things is a major source of pressure.

Stress is only ever accumulated at the end of the week, usually due to the effects of unsolved problems or some drastic side projects.

Compared to the implementation of “stress” in other games such as Oxygen Not Included and Darkest Dungeon, stress in Tharsis has a subtler effect. To be precise, it mainly affects the “side projects” that the crewmembers come up with during the end of the week.

Prior to the allocation of food (or any “meat”) prior to the start of the next turn, a list of choices appears. The player must select one of these choices to implement; there is no opting out.

One of the options may involve one or more of the crewmembers; the possible permutations depend on the number of crewmembers that are still alive. There are usually at least two choices, however – even if the player has only one crewmember left.

The effects of the choices depend on the severity of the stress levels of the crewmembers that are associated with the choices. More severe stress leads to nastier effects, but greater benefits. However, options that are associated with higher stress levels tend to have negative consequences that outweigh the positive ones.

DEPLOYMENT:

For whatever reason, a crewmember can only be assigned to just one module per week. The player should make this decision wisely. For example, crewmembers with many dice should be assigned to modules with severe events that threaten a game-over.

Preferably, the player should be able to spend all of the dice of the crewmember; most events, modules and crewmember specialties allow for this. However, any unspent dice is outright wasted.

There could perhaps have been a feature to let crewmembers recover unspent dice so that they can be spent on some other module, but at the cost of losing one more die for that one more deployment.

MODULES:

One of the space-ship’s modules is always busted; there is no changing these, even in the “missions” that are not canonical. The others are functioning, but with the loss of the aforementioned module, the others are fraught with problems.

When they are not burdened by problems, however, the player can use them to obtain benefits for the crewmembers. For example, the Life Support module can restore all of the dice of the crewmember that is operating it, if the player could obtain the dice to do so.

Indeed, it might be prudent to ignore modules that are hurting from events, just to give a crewmember a leg-up for the next turn. That is, assuming that the player can ignore the events.

MODULES DO NOT RETAIN DICE:

Some modules have features that require more than one dice to trigger their effects. Any dice that is spent on filling their slots is retained for the duration of the week, in the hope that another crewmember can operate the module and give dice to its system.

However, at the end of the week, all modules lose any dice that has been spent on them. They are not like the research system, which does let the player retain dice.

CREWMEMBER SPECIALTIES:

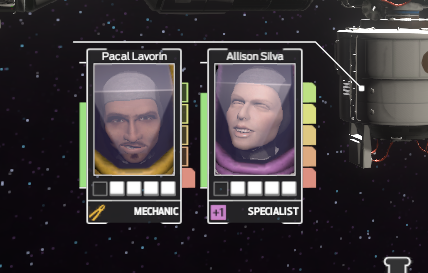

Each crewmember is unique; there cannot be two copies of any crewmember, obviously. The player starts with only four crewmembers unlocked.

Each crewmember has a specialty. Generally, this specialty only confers its benefits if the player can obtain the dice to do so. In the case of three of the initial crewmembers, the player needs dice of 5 or more, which can be rather costly because these dice would have been useful for the repairs of problems.

Any crew specialty that requires dice to be triggered can only be triggered just once; the slot for that specialty is filled and can no longer receive any more dice.

Among the crewmembers, the only specialty that does not need dice is the Engineer, whose specialty is having one extra re-roll. This is not always a great advantage, because re-rolls run the risk of dice triggering hazards (more on these later).

UNLOCKING CREWMEMBERS:

In the main game mode, not all crewmembers are available from the get-go. The rest have to be unlocked by grinding quite a lot of statistics, as is typical of a rogue-lite like Tharsis. These unlockable crewmembers do have specialties that are a tad easier to use, because they require dice with facings of less than 5, so they might be what the player needs in order to complete a playthrough.

“EVENTS”:

Randomized events are nothing new in games with luck-dependent gameplay. However, in most of these games, there are good events as well as bad ones. In Tharsis, all of them are bad.

The player is shown the number and severity of upcoming events, the convenience for which is explained through some unconvincing science-fictional gimmick. Anyway, the player can estimate the size of the proverbial turd that would be hitting the proverbial fan. However, where the pieces of the turd would land is unclear, and in Tharsis, that randomness is the distribution of the events throughout the ship.

One module can only ever have one event. Therefore, any incoming Event would hit modules that do not already have an Event (that the player did not manage to resolve in the previous turn).

REPAIRS:

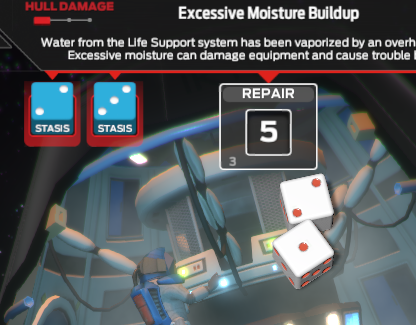

Every Event comes with a counter that represents the amount of attention that the crewmembers need to give in order to solve the problem. Gameplay-wise, the player sends dice into the counter, reducing its number until it reaches zero. When that happens, the problem disappears and the module returns to full functionality.

The severity of the Event determines how high the number is. The number can never go higher, but as long as it is still around, the negative effects of the Event will be fully applied.

There are other ways to effect repairs than allocating dice to them, but these are rarer and come with considerable opportunity costs.

GETTING WOUNDED PASSING THROUGH DAMAGED MODULES:

When a crewmember is deployed to a module, he/she has to travel from the module that he/she was in to that module, assuming that it is a different one. The modules that he/she would pass through are not shown, but the space-ship has a simple enough layout that the route would be obvious.

If their routes include passage through modules that are affected by events, they will be injured; one point of health is lost for each damaged module that is passed through. Attempting to move out of a damaged module also reduces health. The game will forewarn the player about this, so the player can reconsider the deployment of crewmembers.

The crewmembers could have travelled along the exterior of the space-ship to reach another module, but this would have been a risky thing to do. (Real-life scenarios certainly do not encourage this either.)

Oddly though, staying over a week in a damaged module does not injure a crewmember.

HAZARDS:

The event that is afflicting a module introduces complications in the form of hazards. There are three major of types of hazards: Stasis, Void and Injury. These hazards stymie the player’s allocation of the dice that are rolled, and are the second-most frustrating part of the gameplay after the fickle dice rolls.

Stasis freezes dice, preventing them from being re-rolled. However, they can still be used. Injury inflicts an injury on the deployed crewmember, and can be fatal. If the crewmember dies, all dice are lost and cannot be allocated at all. If the crewmember survives, the dice can still be used. Void hazards remove affected dice entirely, and are generally the most infuriating.

All these hazards are represented as coloured dice; the colours are colour codes for the types of hazards. The coloured dice have facings that indicate which die roll results will be affected. For example, if a Stasis hazard has the facing of 3, any dice with the outcome of 3 will be affected by Stasis.

The severity of an Event determines how many die roll outcomes would be affected. The worst of them can affect up to three numbers, meaning that on average, half of the player’s dice rolls will be stymied.

Some modules and research projects can allay the influence of the hazards, possibly even negating them. However, such measures are rare. Rather, “Assists” would be the main method of dealing with hazards.

ASSISTS:

“Assists” represent the mechanized/automated aid that the space-ship provides to the crewmembers. An Assist is spent to negate the effect of a Hazard whenever it is triggered. The player can only store up to three points of Assists, and it would be rare that the player would have enough.

The main problem with Assists is that the player is not given the option of choosing which Hazard-affected dice to save with Assists. The game’s prioritization of which die to Assist first is not immediately clear either.

RE-ROLLS:

After a crewmember’s dice have been rolled, the player can choose to either allocate dice, or re-roll them. The player can only re-roll them so many times, however, and there are risks too.

If the player chooses to do a re-roll, the player might want to place some dice into the dice holder, if he/she has not allocated them already but wants to retain them. The dice holder is there for the sake of players who ruminate.

The main risk of re-rolling is that the re-rolled dice can trigger Hazards too. Obviously, the dice would not do so if they have already been frozen with Stasis or disappeared to the Void. However, the dice can trigger Injury, even if they have triggered Injury earlier.

POKING DICE:

The game allows the player to poke the dice while they are rolling, but the effect of the pokes seems to be rather minimal. Furthermore, the dice travel across a considerable portion of the screen, making it difficult to poke them. They also have enough momentum that the pokes do not do much.

There had been other games with more effective dice-poking, such as Warlock of Firetop Mountain. The one in this game is just disappointingly ineffective.

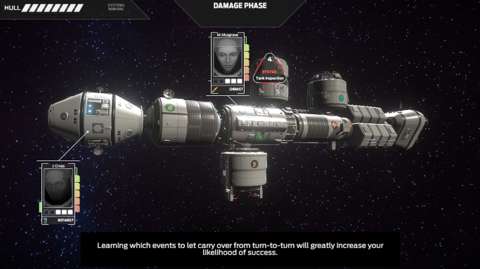

HULL:

The modules will not be destroyed like the one that had been ripped apart, but problems with them will damage the overall integrity of the space-ship’s superstructure. The Hull meter represents this integrity. Obviously, if the Hull meter goes down to zero, it is game-over.

The Hull meter generally goes down at the end of the week, after the effects of unsolved events have been considered. It can also go down if the player selects side projects that sacrifice Hull points for some benefits.

The Hull meter can be replenished. The main source of this is the specialty of the Mechanic crewmember, so it is not uncommon for players to have him on just about every run. There are other sources, though they are not as readily available.

“RESEARCH”:

The astronauts may be in dire straits, but sometimes, they can gain pick-me-ups. This is represented through the “research” system.

In actuality, the word “research” is a misnomer here. Most of the options that the “research” system provide do not resemble anything that is related to R&D. Rather, it is a system that has been put in place to absorb any unused dice.

Speaking of which, it has six slots, one for each facing of a die. The player can place a die with the appropriate number into one of the slots, after which its facing changes to that of a beaker. The number of filled slots represents the amount of “research” points that the player has.

The points can be spent on one of the options that the system provides. The dice in the leftmost slots will be spent first, which is perhaps a wise design decision because dice with low outcomes often have little worth other than being placed in the slots.

The options are generally wholly beneficial, and can be deployed readily in just about every screen except the end of the week one. Indeed, a well-timed cashing-in can make a tremendous difference.

Aside from its lousy name, this feature is the main saving grace in the gameplay designs of Tharsis.

“MISSIONS”:

Some months after the release of the game, the developers implemented a different gameplay mode. This gameplay mode sets up scenarios with special circumstances that can be quite challenging. For example, there is a scenario that outright disables the “research” system, so the player has fewer means of allocating dice.

Generally, these scenarios require the player to have the ship and at least one of its crewmembers hold out until a certain number of weeks have passed. The scenarios are also not subjected to the limitation of having to unlock crewmembers for use. In fact, the player is given specific crewmembers and is expected to make do with these.

Ultimately though, these scenarios are just there to satisfy players who want strategic challenges. They do not contribute anything to the story, and completing them does not yield any further gameplay content.

SCORING:

When the player loses or wins any playthrough, the player is given a score based on his/her performance. Things like food harvested and repairs made contribute to the score, whereas things like stress accumulation detract from the score.

Ultimately though, this feature is only there for the ardent fans of the game. They would have to be rather special people if they could have the determination to compete with each other when the gameplay is rather luck-dependent.

WRITING:

One of the main reasons to keep on plugging away at this infuriating game is the story-telling. There is rather good writing for the game, especially for the cutscenes. Even though the story does not explain everything, there are enough statements by the narrator that experienced story-goers can piece together a plot of sorts.

However, there are some disappointing bits about the writing. For one, the writing for the side projects is not convincing. The side projects are described through the statements of the crewmembers, but sometimes the gist of their statements is not convincingly associable with the effects of the side projects.

VISUAL DESIGNS:

The game uses a mix of visual designs. There are 2D sprites and layers for things like the starry background of space and the view of Mars from orbit.

There are 3D models for the space-ships and the astronauts. These models have enough detail to be recognizable as objects that would appear in a space-ship. For example, the modules of the space-ship are recognizable as being similar to those that are used in real space vessels, such as the tapered cone that is the flight module. There are not a lot of animations to be had, however.

Then, there are the more detailed 3D models for the heads and shoulders of the crewmembers, which are used for their animated character portraits. Interestingly, these are used for their emotional expressions too, such as when they are stressed-out or are taking injuries.

Finally, there is the hand-drawn artwork for the cutscenes. These never show the faces of the crewmembers, with the exception of at least one person that happens to be the narrator. Still, they have enough of the appropriate qualities to give the story more gravitas than it actually has.

SOUND DESIGNS:

The only legible voice acting to be heard are the voice-overs for the narrator in the cutscenes. Interestingly, there are two versions of the narrator: one for when the team leader is a lady, the other for when it is a guy. It is not clear how the game decides which to use, though, but it uses the same set throughout the playthrough.

The not-legible voice-acting are heard whenever the crewmembers die. These are definitely not pleasant sounds.

The music is rather pleasant to listen to, despite the infuriating gameplay. Perhaps this was intentional, but it would be difficult to appreciate it when the player is fuming over fickle dice rolls.

Next, there are the sound effects. The dice make clacking noises as they roll about, which is a touch that would have been neat if the rolling dice were not so worrisome. Indeed, most of the sound effects are worrisome, because most of them had been made for bad occurrences, like the hull taking damage.

SUMMARY:

At first glance, Tharsis would be a nightmare to anyone that does not like luck-based gameplay. The rolling of dice would already be cringe-inducing, but having them frozen, disintegrating or hurting crewmembers would have been outright hair-pulling infuriation.

Yet, Tharsis has some interesting mechanics, namely the allocation of dice with different numbers to slots that grant different benefits. If the game has focused more on these than the other gameplay elements, especially the hazards, Tharsis would have been so much more enjoyable.