Considering the complexity and hybridization that's en vogue in the games scene these days--where role-playing games are being grafted onto online arenas, and shooters are also looters--it's not so surprising to see a sort of reactionary minimalism begin to appear at the fringe, its adherents calling for a trimming of fat and a renewed focus on more pure genre experiences. Spacecom is just that sort of endeavor, and it angles for a simpler sort of strategy game, divorced from superfluous abilities and special effects.

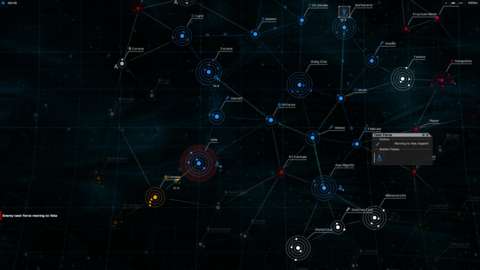

Spacecom presents a flattened galaxy in abstract: ringed orbs for planets, and lines to string them into daisy chains of interstellar travel. The goal is simple: occupy, defend, and destroy as necessary en route to the opponent’s homeworld. Modus operandi stays true to strategy game traditions here: amass resources and production centers to churn out units as efficiently as possible, maintain your supply lines, and simultaneously command your units in the field. It's a two-button affair: left click to build a unit or select an existing one, right click to set a destination. The gory bits--hat is, the ship-to-ship combat, annexations en force, and planetary bombardments--are all handled in abstracted automations where damage is done by one side or the other when their respective meters fill.

The design of the units themselves is characteristically restrained. They look like little Imperial Star Destroyer wedges, trisected into highlighted parts to show which of three roles they fill. A highlighted prow means a battleship, which fares the best in ship-to-ship combat. A highlight at the stern signifies an invasion unit, which can seize planets and convert itself into stationary defenses. Siege units, ever the awkward middle child, straight-up destroy planets, rendering them unusable by anyone. Seeing one of the latter sneak into one of your undefended manufactories is a real downer, let me tell you.

Problem is, it can take some squinting to figure out which unit that rogue ship actually is. The little, mutely colored buggers can rotate every which way, so at a glance it's hard to identify which part of their thorax bears the telltale highlight. It's just one small example of a broader inscrutability, inscrutability that's particularly disappointing in a game with such simple visual elements.

Spacecom presents a flattened galaxy in abstract: ringed orbs for planets, and lines to string them into daisy chains of interstellar travel.

For one, units stack, appearing as a single ship with multiple sections highlighted. An adjacent number gives you only the sum total of units therein. So when you eventually deduce that the single wedge advancing on your frontline is not one, but seventeen units, you'll still need to click it for a more detailed breakdown and count the battleships, invaders, or siege units by hand so that you can plan accordingly. Even at slow game speeds, the seconds this takes are precious, and sometimes delay your response long enough to turn what might have been a battle won into terrible loss. Planets themselves are similarly coy about their contents, and if you direct your fleets to battle over one, they disappear; you'll have to click the red circle that forms in order to witness the proceedings.

The delays mount. You need to watch the battles play out, because it's frequently unclear who'll win until the deed's actually done. There's a ribbon of text above the battle abstract that attempts to predict the outcome, and the way it flits about is comically capricious--from "everything is lost" to "winning slightly" to "losing slightly" to "victory at hand." That's because while units in Spacecom damage one another at regular intervals, their targets are chosen at random. So the enemy's three ships might beat your five, if yours happen to spread out their fire while your opponent's concentrate theirs.

That little bit of unpredictability might normally have an appreciable effect of keeping battles from becoming rote, but there are more engrossing strategic concerns that you'll want to devote your attention to. That's particularly true if you've roped in a friend or two, because there's a strong board game quality to Spacecom--I'm reminded of Othello's old mantra "A minute to learn, a lifetime to master." Or the board game Twixt, with its supply lines of points and bridges that, when broken, would see your best laid plans thrown off kilter. With a human opponent, there are plenty of strategic gambits to play--feints, distractions, and tactical retreats are all effective, and I've got one particularly nefarious opponent to thank for learning the horror of that lone siege infiltrator. Units are excruciatingly slow to respond, but this keeps the focus on the right skill: the ability to see three moves ahead.

That's only the case if you're playing against a fellow human, however. After being humiliated in a few matches, I decided to try my hand against five expert-level AIs, with the hope of honing my abilities. I figured I'd get a workout, hard-pressed on multiple fronts. Imagine my surprise when I stormed through all five in rapid succession, finding the opposition milling about, producing only intermittent siege units--and not at their production centers, but at their homeworlds, in apparent disregard for the rules I'd understood to apply uniformly.

That sort of thing just won't do. When systems reach a certain level of complexity, they start prompting greater expectations. Why can't you set rally points to automatically ferry your newly produced units where you need them? Why can't you specify hotkeys for fleets or production centers? Why does everything need to be clicked in order to see what it's doing? Auralux, Galcon...these games do minimalist space strategy better. Perhaps the hard constraints of a mobile device are more conducive to pared-down design than any self-imposed rigor can be.