INTRO:

Nostalgia is a strong emotion that can have people doing less than wise things. An example of these is backing a crowdfunded project to somehow ‘bring back’ something that they had treasured in the past. Rose-tinted glasses often obscure one’s memory of the past and blind them to complications in the reality of the present. These complications include the fact that there are many things that are beyond their control and the outcome is not always one that they expect, nor is it one that is guaranteed.

The remake of Gabriel Knight: Sins of the Fathers is one such example. It is one of the two games promised by the Kickstarter project that was proposed by Pinkerton Road Studios and the creator of Gabriel Knight, Jane Jensen.

After the less-than-great reception of Moebius: Empire Rising, Pinkerton Road had its next game, “Mystery Game X”, be a remake of the first Gabriel Knight title. Although the game is certainly far from just a spruced-up version of the original, it has plenty of rough edges.

PREMISE:

Understandably, the story of this remake is a recycling of the one in the original. Gabriel Knight is an aspiring writer in New Orleans, but he had not done much beyond opening a bookstore that mainly sells his books (and they are not selling well).

Lately, there have been homicides with peculiar circumstances; the victims appear to have been killed in rituals. Looking for materials for his next book, Gabriel begins investigating these murders, with the help of some friends. Eventually, he uncovers a dark secret that had been around for generations, and has something to do with his lineage too.

POINT-&-CLICK:

This remade game is a point-&-clicker. It has most of the UI conveniences that followers of the adventure game genre would be expecting from a game with competently designed user-friendliness. For example, clicking on something far away will have Gabriel immediately fading out and reappearing at the target location.

SLOW GABRIEL:

The conveniences are all the more welcome, after certain dubious design decisions have been revealed. Among these is Gabriel’s leisurely walk. Of course, most situations do not require urgency on his part; even if it looks like Gabriel has to hurry in one situation but keeps failing, that is an indicator that the player is approaching the situation in the wrong way.

Therefore, one could argue that Gabriel’s slowness is not an issue – most of the time. However, it becomes a problem if the player wants him to interact with things that are close to each other; the fade-in/fade-out script will not trigger in this case, so the player has to wait for him to scoot over from one object to another. (Scooting over has its own inanity, as will be described later.)

INVENTORY:

As to be expected of a protagonist whose origins are in the early 1990s, Gabriel has considerable pocket space in his clothing to stow away many kinds of things that might not seem small enough to keep on his person. Although he may not be able to carry things like large boulders, he can stuff multiple bulky things like parcels and thick books into his jacket without any complications.

CONTEXT MENU:

Sins of the Fathers is one of those games that uses context-sensitive sub-user interfaces for interaction with something. Clicking on something brings up a radial menu, with each ‘spoke’ in the radial menu representing a possible action that can be done with the object of interest.

However, not every action can be carried out. Undoable actions elicit remarks from Gabriel, the narrator or another character. As any veteran follower of adventure games would expect, this is something that the player would want to pursue anyway, if only to find another amusing line that the writers and voice-actors may have made. (Unfortunately, many of the remarks are little more than stock negatives.)

USING ITEMS:

In other adventure games, the player has to access the inventory, click on something to turn the cursor into said something, and then bring the cursor over to some object that is on-screen. This can be tedious.

This is not the case in this remake of Sins of the Fathers. The player still has to open the inventory and click on an item, but the item occupies one of the slots in the context menu, specifically the slot for using something in Gabriel’s menu with something in the environment.

Unfortunately, not all unsuccessful attempts to use something with something result in unique remarks.

COMBINING ITEMS:

A point-&-clicker that respects the roots of the genre would not be without the gameplay element of mashing something into another thing. Sins of the Fathers does this too, but not in a smooth way.

Clicking on something in the inventory highlights other objects that the item could possibly combine with. The player only has to click on that other item to proceed with a combination attempt. This would have been simple and convenient, if unsuccessful attempts did not result in the user interface believing that the player wants to select the other object. In these cases, the player needs to click on the first item again to select it in order to attempt combination with other objects. Furthermore, an unsuccessful attempt at combining something might not result in a unique remark.

Most item combinations seem plausible, but there are some that can be difficult to believe. Chief of these unbelievable ones is the conversion of Gabriel’s trenchcoat into a priest’s habit. Granted, the habit has a simple design with straight cuts and next to no ornamentation. However, the habit appears to be made of a fabric that is noticeably different from that of Gabriel’s trenchcoat.

(Incidentally, the conversion was more believable in the original 1993 version of the game, when fabric texture is not visible on the sprites for the clothes of characters.)

CONSUMING ITEMS:

Successful attempts at using an item on something in the immediate environment generally causes the item to somehow disappear from the inventory. Of course, this is the game’s way of informing the player that the item is no longer needed; this is par for the course in the genre anyway. However, the item might be returned to the player’s inventory too, thus indicating that there is more to do with it ahead.

DEATH:

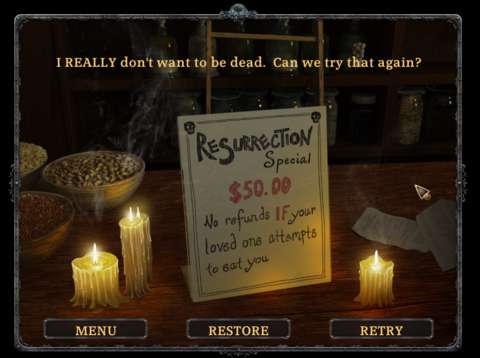

Gabriel Knight does not have plot armour. There are situations in which he is in mortal peril; if the player makes the wrong decision or tarries overlong, he dies. The player is treated to a death-rattle animation using Knight’s 3D model, or is shown a series of comics that end with his demise.

Of course, Gabriel’s death leads to a game reload prompt, so it is just a mere inconvenience to the player (assuming that the player is not deliberately trying to have Gabriel killed, of course).

TRAVELLING:

New Orleans is a city/metropolitan area, so it is large enough that moving about on foot is impractical. Fortunately, Gabriel has a motorcycle that lets him go from one end of the city to another rather quickly.

In-game, travel is represented by diagrams that depict a map of New Orleans and the French district. The map can be brought up at almost any time, as long as Gabriel is still in New Orleans. Icons appear on these maps, representing the locales that Gabriel can go to. Going to them is as easy as clicking on these icons.

PASSAGE OF TIME:

Travelling does not take time, even though New Orleans is of considerable size. Rather, the passage of time is determined by the progress that the player has made in the playthrough. After the player has enacted enough solutions to obstacles/problems, as pre-determined by the coding for the game, the narrator mentions that it is getting late and Gabriel is heading home.

The passage of time is not always reflected in the locales either. For example, a scene by a lake seems to be perpetually at the time of sunset.

Incidentally, the storyline is segmented into days. Every day almost always ends with one of Gabriel’s dreams/nightmares, which become increasingly more complete and vivid as the days go by.

The story is linear; so is the scripting for the appearance of new leads, problems and events. Thus, the progression of days does not really contribute much to the element of player agency, or what little is there in the first place. However, it does matter if the player is looking for “100% completion”, or the exploration of all content there is in the game. There are optionally-pursuable tidbits that change from day to day, such as the newspapers that Gabriel reads and the radio broadcasts.

SCORE:

This remake retains the score rating of the adventure games of yore. This would be of interest to players with completionist streaks.

The mandatory story-related content provides the bulk of the points that go into the score. The other points are provided by the aforementioned optional tidbits. A chime conveniently sounds whenever the score counter increases, indicating that the player has made some progress.

CONVERSATION:

If an adventure game has voice-overs in it, chances are that conversation between the player character and other characters are mandatory for progression. This is the case for this game, and it is just as well, because Gabriel Knight considers himself to be a people person.

Anyway, starting a conversation typically involves approaching a person. More intricate 3D models of the heads and shoulders of the characters appear on-screen, expressing their current mood. In between the models, there are text boxes showing the conversation subjects that Gabriel can bring up.

Most conversation options, once explored, disappear from the list; these often involve character exposition. Some other conversations can be repeated; these are associated with things that the player has to do in order to progress in the story. Furthermore, If they happen to contribute directly to the progression of the game, the conversation options are labelled yellow. They disappear after the player has performed said things, though they might only be available to perform days later.

NEW ORLEANS:

Most of the game takes place in New Orleans and most of the characters are the people of that city. As befitting the history of New Orleans, the places and characters are diverse.

A player that is not already well-versed in anything New Orleans might have to do some research to confirm for himself/herself that anything that is seen in the game is authentic. Of course, this is not always the case, if the supernatural elements of the story do not make this clear already. There are also puzzles that are mere versions of ages-old puzzles dressed up with voodoo imagery. For example, there is a puzzle with cryptic-looking symbols that turn out to be little more than a substitution cipher.

Nevertheless, some of the characters’ descriptions about New Orleans culture and its special branch of voodoo can seem convincing to a layman. The vagaries of puzzle designs and supernatural things aside, there is the impression that the developers have invested adequate effort into researching and implementing the cultural elements of the game.

SOME CLEVERLY OBSCURE PUZZLES:

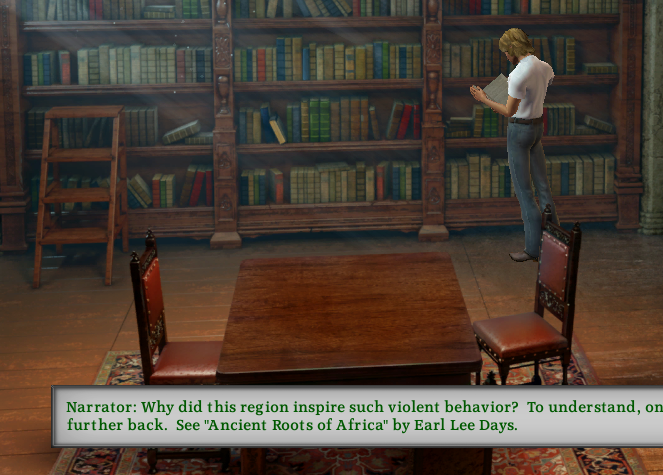

Most of the puzzles in the game can be figured out by examining clues in the vicinity of the locations with these puzzles, but there are some that require the player to remember snippets of text and observations about other things that are elsewhere. These do happen to be related to the puzzles, but the player might only piece such clues together if he/she has bothered to remember details that might have seemed to be mere filler. One of the puzzles is shown in one of the screenshots in this article.

CHARACTER DESIGNS:

The first character that the player would be introduced to is, of course, Gabriel himself. The introduction begins with his bewildering nightmares, but before the player can feel any sympathy for him, the game shows his lackadaisical and carefree side. The storytelling also establishes very early on that he likes women a lot – perhaps more than they would like him to. He can seem off-putting to some people, but for players who are used to protagonists with outrageous flaws and quirks, he would be yet another typical not-boring adventure game hero.

Gabriel has some witty remarks, some of which can be heard when the player attempts to use things on him. These particular remarks make it clear that he is quite vain, but interestingly, he refrains from making unseemly remarks about other people (with the exception of women, most of whom he would hit on given any opportunity).

Another series regular, Grace, is introduced early on. She is established as very much the only woman who could tolerate Gabriel’s attitude on a daily basis, and she also has plenty of witty remarks that Gabriel finds amusingly hurtful. Then there is yet another series regular, Mosely, who is Gabriel’s childhood friend and a dependable ally, albeit one with questionable fashion sense and less-than-wise eagerness to help Gabriel.

The other characters in Sins of the Fathers are less memorable, though perhaps that is because most of them would only appear in this game. Nevertheless, some of them are interesting, such as a certain Haitian with his opinions on voodoo and mostly convincing accent.

Perhaps the most notable character designs are the differences that the characters have compared to their original versions. For example, there are the changes for Gerde Hull, who is the caretaker for a certain German land-owner. In the original game, she had a much more stereotypical appearance – perhaps even goofy by today’s standards. In the remake, she has a much more formal air to her.

If there is any criticism to be made about the character designs, that would be the sometimes unconvincing aspect of voodoo culture that some of the characters have. More often than not, Gabriel resorts to exploiting this part of them in order to get something from them while they are distracted. The chief example of this is getting a voodoo lady to do a dance, except that her dance does not involve looking at him but rather at the player.

VISUAL DESIGNS:

This remade title’s visual designs are a mixed package of labour of love and slap-dash effort.

Gabriel’s animations are believably human, most of the time. The problem though is that they look so forced to the point of being goofy. This is most notable when he is stepping sideways; the way he scoots over sideways is silly, like a human trying to imitate a crab.

His walking animations are also dubious: in some scenes, he strides around, as befitting the urgency of the situation. (It so happens that he is in his trench-coat when this happens.) At other times, he strolls and sometimes looks like he is jogging on the spot. The worst that his animations can get to is that Gabriel can walk out of bounds; such occurrences are rare, but they happen if the game somehow gets conflicting inputs from the player. (This leads to an imminent crash.)

The animated heads and shoulders that are used in conversations are perhaps the best-done visuals. They are detailed enough to bring out the most notable characteristics of the character’s appearance (at least from the shoulders and upwards). For example, there is Gabriel’s luxurious (but slightly greasy) hair. More importantly, the facial animations are believable, though perhaps brief because the faces of the characters return to their default state shortly after a conversation ends.

The rest of the visual designs are the mostly static hand-painted artwork for the environments. They are quite lavish, and there are some particle effects to prevent the artwork from looking too still. There are also 3D objects overlaid onto the environment, such as billowing curtains that look quite believable (though they could have been animated 2D objects that have been in-laid into the level).

However, the 3D models of characters look out of place. The first notable thing about this is that their shadows are not convincingly projected, if there are shadows at all. The lighting for the characters’ models is also not consistent with the lighting of the environment.

GRAPHIC NOVEL SEQUENCES:

There are some scenes that are depicted with graphic novel panels. Incidentally, these scenes include explosions and magical phenomena, which would have been quite expensive and costly to make in 3D or even in full-screen 2D. These scenes can seem disruptive at times, but they are otherwise well-done.

VOICE-ACTING:

The voice-acting in this game is generally adequate, at least for someone who is not particularly familiar with New Orleans accents. There are other accents to be heard, such as Haitian, German and French Creole, though again, how convincing they are is up to the player’s familiarity with them. More importantly, the voice-actors and –actresses with these accents managed to deliver their lines with convincing emotional inflection, at least most of the time.

There are occasions when the voice-acting for some characters falter. Angry Gabriel Knight, in particular, is laughable; the voice-actor is trying to sound angry while forcing a Southern USA drawl.

MUSIC:

Robert Holmes composed the music for the remake. Most of the music is a re-rendition of the music in the 1993 original, which is expected. Having access to more modern music-production technology meant that the re-done music is a lot more energetic and varied than the original, which is of course an upgrade.

SOUND EFFECTS:

There are not a lot of sound effects to be heard. There are the chimes and flourishes that play whenever the player makes progress, and the ambient noises that are associated with the environments that Gabriel is in. Many of the louder and hectic sounds are only heard in the graphic novel cutscenes.

CONCLUSION:

As to be expected of a remake of a classic point-and-click adventure game, Sins of the Fathers has more-than-decent writing and story-telling. Yet, the writing and story should not be so easily counted amongst the game’s upsides; after all, these have been established by the original game decades ago, and mostly recycled in this remake. Furthermore, the game sometimes has tepid presentation and bugs in its animation.

Considering these shortfalls, it is difficult to recommend it to people who remember the original but are wary of remakes, but it might appeal to younger followers of the adventure game genre who have not chanced upon Jane Jensen’s works.