The human fascination for the deus ex machina, or the improbable but very convenient solution for a stubborn problem, had led to the conception of many ideas, most of which are expectedly outrageous and fictional. One of these is the concept of superheroes, who have capabilities beyond that of regular humans and who would use this to fight crime.

Of course, it did not take long for others to doubt that all fictional super-powered individuals would use their gifts for good. Despite the conception of supervillains pretty much dashing the notion of super-powers being the solution to the problems plaguing the world (or at least worlds that exist in the realm of fiction), such ideas still led to a segment of gratuitous entertainment that endured to today.

Along the way, comic-book superheroes and supervillains underwent a lot of evolution, characterized by the passing of one generation to the next, each with its own defining traits. One generation of super-powered characters, known as having belonged to the so-called "Bronze Age" of comic-books, was particularly known for having gaudy costumes and appearances, as well as far simpler personalities, goals and lines than those of the very complicated generation of comic-book characters today. Such character designs apparently still hold appeal to long-time comic-book fans.

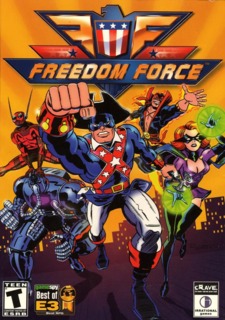

Apparently, the developers of Freedom Force are such fans. In fact, they are fans who are so ardent that they had risked making a game that prominently showcases such comic-book characters and sending it into a market dominated by customers that did not know that age of comic-books so well.

(As a side note, Freedom Force is not to be confused with a 1988 video game, which had nothing to do with superheroes and had more to do with a light gun accessory for the NES. It is also not affiliated with a certain, short-lived cartoon series that also happen to feature Bronze Age comic-book characters.)

Yet, if a player who is unfamiliar with such comic-book themes from this by-gone era can look past these, there is a surprisingly well-designed game to be played and enjoyed. More interestingly, most of the well-done game designs in Freedom Force have to do with the comic-book-inspired characters themselves.

However, the premise of the game has to be elaborated on first before the gameplay, because the former aspect is deeply involved with the latter.

As to be expected from a game with themes that have their origins in the concept of deus ex machina, the backstory in Freedom Force, which is set in a fictional version of the Cold-War era of our world, has the major characters dealing with the consequences of an influx of super-dimensional material known as Energy-X that grants super-powers to anyone that it comes into contact with. A segment of the affected individuals became self-proclaimed superheroes, whereas the rest would go on to become tyrants and warmongers, all gleeful with their new-found powers. The face of the world, as they know it, has been greatly changed by the rise of these super-powered individuals.

In addition, Energy-X also awakened a lot of ancient mythological/legendary creatures, returned dinosaurs to this Earth and gave life to inanimate objects, adding to the troubles across the planet.

Yet, all these problems are really only there as excuses to give the player a great time smashing villains in with super-powers - as well create opportunities for plenty of pun-filled, campy amusement.

The game can be played in both single-player and multiplayer, though the single-player mode is the one that will be offering the most fun as well as the opportunity for the player to derive satisfaction from developing exceptionally powerful heroes to battle enemies that are almost as devastating. Such powerful characters will hardly be seen in multiplayer, for reasons of gameplay balance. The player can choose to use the official roster of characters, create new ones from scratch, or use existing characters as templates for new ones for use in either mode.

In the story campaign, the player starts off with just one of the main heroes of the game, the unrelenting Minuteman who also happens to be one of the most powerful melee combatants in the roster of official characters. Eventually, through the completion of several missions, the player will collect more like-minded heroes who believe in doing good and eventually have enough heroes to form the Freedom Force.

Of course, there cannot be superheroes without supervillains. Throughout the single-player mode, new story arcs will expediently pop up to give reasons for the game to introduce new enemies and friends. Some of the heroes will have their origins included in their profiles in the form of a series of comic-book semi-still images that would be entertaining to those who love deliberately campy stories. The progression of the single-player campaign also rewards the player with cutscenes that depict the background of the villains in the game. (These are also of the amusingly campy sort.)

The villains and heroes who do not get cutscenes still get text-based descriptions to tell their tales. These can be a worth-while read as some of them are witty, if rather brief.

The personality and canon of the official characters aside, the gameplay designs that govern their use in-game would be the aspect of Freedom Force that appeases a wider audience of players. Continuing the brief mention of character profiles earlier, the super-powered individuals in this game have profiles that collate together every important piece of information pertinent to their designs. The character profile is also the first screen that the player sees when creating a new character.

A character profile contains the name of the character, complete with case-sensitive spelling and punctuation (if any), a rendition of his/her/its model to give the player an idea of how the character looks like and animates (which will be important when making a custom character), his/her/its statistics, movement properties, traits (such as personality, which actually has in-game ramifications) and a breakdown of his/her/its superpowers, among other things that are less important but no less significant.

The name of a character would not seem important next to the other things in his/her/its profiles, but it has to be noted here that this is also used as the name for the container file that holds the designs for this character in the game's install directory. Thus, character names have the same limitations as file names in typical OSes: the player cannot use certain text characters like the exclamation mark, hashes and aliases. They cannot use letters with diacritics either, much less non-Latin characters. This is a really minor complaint, but such limitations do crimp the creativeness of players who would have wanted to create characters with themes that are far more foreign from those of the characters in the official roster.

Another restriction that the player would discover in the design of characters in this game is the limited set of officially made animation scripts that can be applied onto character models. There are several kinds of animations that have been made to accord to the personalities of characters, such as feral postures for characters that move in manners beyond that of a human, brawl stances for hot-headed individuals, grandiose statures for those of high self-esteem and a few more, but a discerning player will notice some semblance of repeating patterns in the visuals for official characters (though their overall sets of animations are different from each other's, as will be mentioned later).

However, the player can choose to create custom animation scripts and import this into the game, though this entails the use of third-party software that only dedicated players would go the length to use. Fortunately, Freedom Force accommodates custom animations quite well.

The same can be said of the models for characters, which can be made outside of the game with third party tools and imported into the game, though they have to conform to its technical limitations (which are based on early versions of DirectX 9). With the same limitations in mind, the player can import custom-made graphical and sound effects for super-powers into this game, as well as voice-overs.

However, for purposes of gameplay balance and computational limitations, the game does not allow the player to create custom-made super-powers with their own coding - outside of the use of mods, of course.

A character that has been completely designed will have ratings in terms of points that represent his/her/its advantages and disadvantages. How these points are apportioned will be explained shortly. However, it has to mentioned first that (somewhat-)balanced characters have equal amounts of points in the aspects of advantages and disadvantages.

Secondly, these points will determine the amount of "Prestige Points" that this character has. Prestige Points (PP) give a good gauge of a character's capabilities. This is also the case for characters that are balanced in advantages/disadvantages, because characters with very high advantage points will still have a lot more versatility or durability even if they have disadvantages that are equal in points. Consequently, this also means that characters with greater amounts of points in advantages than they do disadvantages will have greater PPs, the amount of which gets exponentially higher as the ratio widens in favor of advantages.

(This system of advantage/disadvantage points and PPs will also be used in the single-player campaign to give an RPG-like sense of progression, as will be elaborated on later.)

Every character, be they playable or computer-controlled, have their in-game performance governed by "Characteristics", which include the usual RPG statistics such as Strength, Dexterity and Vitality.

However, there are a few characteristics that would raise the eye-brows of those who have yet to know of them, such as "Ego", which apparently has more to do with the character's strength of mind and concept of the self than the one identified by Sigmund Freud. In-game, this determines how resistant this character is to psychic attacks and how good he/she is at making such attacks of their own.

Fortunately, Ego and such other characteristics that would be unfamiliar to many players have detailed descriptions of what they do and what benefits/penalties that they confer onto the character (depending on their ratings). Although the magnitudes of the benefits/penalties are always shown, the exact equations that are used to calculate these are not mentioned.

Generally, characteristics which are higher than 10 in ratings are of better benefit to the character and will be associated with greater advantage points. On the other hand, having characteristics with ratings below 10 is detrimental, and thus contribute to a portion of disadvantage points instead.

The powers (super- or otherwise) of the characters in this game are listed in their profiles. A click on these would bring up a panel that contains their description and technical properties. For the powers that pre-made characters have, they come with brief descriptions of what they do.

The descriptions are not able to inform the player completely about these powers. Therefore, said technical properties also have descriptions that appear via tool-tips. A power can be as simple as a normal melee attack, or as complicated as a special, slow-firing energy ray that not only damages enemies but also steal energy from them and transfers this to the user.

Some examples would be needed for elaboration.

The most common example is the melee attack that generally all characters have by default (though the player can create a character that doesn't have one at all). A melee attack obviously only inflicts damage if it hits the target, but there are factors that determine whether the attack hits or not and what happens after the attack hits home, such as the target's Dexterity rating and any traits that give him/her/it a chance to dodge this (there will be more on traits later).

Some characters can have slow close-combat attacks, which are only suitable for targets that have been locked-down, while others, usually the more limber ones, have very fast jabs and punches that are useful in harrying enemies who are trying to put some distance between them and the player's team members. The speeds for these attacks will be noted in their properties for the meticulous player to take note of.

These melee attacks may have also modifiers like Knock-back, Stun, Confusion or even a mix of these effects that would be familiar to RPG veterans. They will also be noted in the descriptions of the melee attacks, together with the probabilities of these effects occurring on the target when they are hit.

Due to these variants in the properties of melee attacks, there can be characters that are designed to have plenty of different melee attacks, such as the official poster-character that is Minuteman.

An example of a power that has complicated designs is Contain Energy, which the robot-suit-wearing Man-Bot has. It is an energy attack directed at an enemy, which will steal energy from the target and add it to Man-Bot's own vast reserves. However, how much energy is stolen depends on the toughness of the enemy and their resistance to energy-based attacks. Furthermore, there is the drawback of Man-Bot unwittingly releasing an energy explosion that can damage both enemies and friends alike if he absorbs energy over his limits to store them.

There are a lot more powers than these - so much more that describing even the main categories of these powers would be exhausting. It suffices to say that many of them work as intended, and few of them - if any - are severely flawed gameplay-wise. Even a surprisingly powerful ability is balanced by appropriate drawbacks, a good example being the Sea Urchin's astonishingly powerful Riptide kicks that take away a lot of her energy when used.

"Talents" are one subset of the aforementioned traits. Talents are generally beneficial in nature, such as Liberty Lad's oddly named "Combat Luck", which gives him a bonus to his damage resistances. Talents are usually active all the time, but certain status effects disable these, robbing the affected characters of their convenient permanent buffs.

Some "skills" are the representation of the professions or hobbies that these characters practice outside of their day jobs. These often appear to have descriptions that do not suggest that they have any effect on gameplay, such as Liberty Lad's Ventriloquism. However, this does come into play in certain mission designs. Using the example of Liberty Lad's ventriloquism again, there are segments within certain missions that have scripts that can be triggered with Liberty Lad's presence; this can make these segments easier, such as Liberty Lad conveniently using his ventriloquist skills to lure away portions of enemy forces.

Generally, what has been described above are beneficial to the character, either giving them boosts to stats or increasing their versatility in approaching obstacles in the game. Therefore, each of these contributes to the amount of advantage points that a character has.

Other than characteristics below 10 in ratings, another source of disadvantage points is, well, disadvantageous traits, which are appropriately lumped under their own category for easy examination. Many of these traits are hilarious and sometimes even outrageous, as befitting comic-book heroes of that time which had amusing flaws and weaknesses worked into them by their creators (usually in response to feedback from comic-consumers that they were too unbelievably powerful, even for fictional super-powered characters).

For example, there are disadvantages in the form of "Psychological Limitations", or in other words, chinks in their personalities. These have impact on both gameplay and are also used in scenario designs. A specific example is El-Diablo's Psychological Limitation of "Sucker For A Pretty Face", which will come into play if he is forced to fight against pretty villainesses. This trait triggers hilarious comments as El-Diablo knocks out these ladies, and also slightly reduces the damage that he can inflict on them.

All these character designs are available in the character creation feature of the game. Disregarding third-party mods, the developer-made repertoire of options may be set in concrete, but they are plenty varied enough for combinations that create characters that are very different from the official ones.

Unfortunately, the traits that have more significance to scenario designs cannot be so effectively used on custom-made characters, as the aforementioned scenario designs mostly affect the official characters only. Moreover, these traits are completely useless in multiplayer mode, due to the narrow designs for this, as will be mentioned later.

The story campaign has the player using altered versions of the default and balanced variants of the official superheroes. These versions start out little different from the latter, but they have the capacity to take on upgrades through the expenditure of PPs, which can be earned through the course of the campaign by completing missions, achieving side objectives, staying true to optional conditions set by the map and defeating enemies, which have PP bounties of their own.

In the campaign, the PP score that the player has accrued thus far represents the fame that the Freedom Force as a whole has gained from their heroic actions. This fame would not be of much significance to gameplay during missions, but it does unlock new official superheroes for use in the campaign when it reaches thresholds that are equivalent to their starting PP value. Unlocking custom-made characters also requires the accrual of PP equivalent to their own PP values.

In addition, every character gains experience from the completion of missions and add these to their own individual accounts, but other sources of experience earned during the mission is exclusively granted only to superheroes that have joined the four-person team for the mission. The experience that these individuals have gained can be used to improve their powers, unlock new ones or obtain new (usually beneficial) traits (if he/she/it does not have his/her/its powers set in stone already).

As mentioned earlier, gaining more advantage points (i.e. gaining more skills and enhancements) results in an exponentially greater gain in the Prestige Points of the character, and this is depicted in a similar manner in the mechanic of character advancement. As a character grows stronger and more versatile, the player has to spend more and more experience to improve him/her/it.

There is a limited amount of experience that can be obtained through the campaign (without resorting to cheating), yet there is a variety of official characters to spend these on. Therefore, exploring the progression of the powers of various characters offers a lot of replay value - if the player doesn't mind playing through the same missions over again.

The player can also import custom-made characters, but unless these characters have been designed to have the capacity to advance, i.e. have powers that are locked away until the necessary amount of experience have been invested in them, they will only waste any experience that they earn alongside the official characters.

The enemies that the Freedom Force faces in the campaign also happen to be created using the same character creation tools; some of them, especially the ringleaders of villainous forces, happen to be available for use in multiplayer as well. The rest are goons that serve as fodder for the player's team to eliminate and thus feel good about the prowess of his/her superheroes. (They are also available for use in multiplayer, though their multiplayer variants have been understandably powered-up to match the others.)

However, as the campaign progresses, even the goons become more difficult to handle, much more so for their bosses. Nonetheless, neither bosses nor goons would feel too cheap because just about any combination of team members can defeat any boss, given enough prudence on the part of the player in making use of their powers in fights.

In addition to having a rather complex system for the design of supervillains and superheroes, Freedom Force has surprisingly meticulous designs for levels, which can look deceptively simple due to their comic-book-inspired aesthetics.

The level designers did not just place simple-looking batches of polygons that resemble buildings, lamp-posts, furniture, lab equipment and other assortment of objects that match the current environment in play. They are also pegged with a variety of properties, such as being volatile (which means that they can explode), flammable (e.g. they can ignite), light (which means they can be picked up by just about any character) and heavy (which means that they can only be heaved around by super-strong characters), among others.

These properties allow characters to make use of them in practical, if often destructive, ways. An example would be Man-Bot ripping up a lamp-post to give himself a much-needed extension in his reach in close combat. However, while hitting enemies with lamp-posts give him bonuses in reach, damage and a widened arc of collision for his melee attacks, he cannot use the lamp-post forever as it will degrade and eventually break.

The same level design system also incorporates the effects of collateral damage. Powers and attacks can have area-effect properties, such as the aforementioned swipes with a ripped-up lamp-post and El-Diablo's Fiery Blast power. These can hit things other than the intended target(s), including non-combatants like civilians and buildings in the city. Whatever the game tags as "public property" will confer score penalties onto the player if his/her team members damage them.

This is especially important in the campaign, as these penalties will reduce the fame of Freedom Force upon the completion of the current mission and the tallying of the scores. Furthermore, missions that take place in maps that have civilian areas will have thresholds on these penalties, which when reached, will cause the player to immediately fail the mission.

In addition to environmental objects, levels have canisters that contain the various forms of Energy-X. They also happen to float and emit sparkles, which is a visual convenience. These canisters, which are handily colour-coded, can be collected by characters for their benefits, which can be experience rewards (which only benefit the character that picked these up), prestige rewards (as odd as gaining corporeal prestige from canisters can be), health replenishment or energy refills.

The ones that replenish health are particularly precious, though not because of what they do (in fact, they are quite unremarkable), but because there is no character that is capable of healing himself/herself/itself or others. There are some characters that can regenerate, such as The Bullet, but they still regenerate rather slowly. (Custom characters can have greater regeneration rates, but these have astonishingly high PP costs.)

This results in every mission or match feeling like a battle of attrition, which is not exactly in vogue with the themes of Bronze Age comic-books, which had combat being resolved much faster and expediently (and often in a campy manner). On the other hand, the game somewhat compensates by having the mechanic of "Heroic Revivals", which gives medals of sorts to each superhero that the player can expend one at a time to immediately revive him/her/it if he/she/it is knocked out in battle.

Unlike health, characters can more easily regenerate energy, which they consume when using powers that require more exertion. In fact, the game has very liberal designs that allow characters to regain energy quickly or even transfer them around, such as Man-Bot's power to give energy to allies from range.

The gameplay designs for missions and combat that had been described thus far would encourage the player to plan fights efficiently, as a strategy game should. In fact, several missions into the campaign, the player would realize that the gameplay is a lot deeper than the gist of sending a team of superheroes to beat up some evil chumps would suggest. For players who had been expecting simpler gameplay and are at risk of being overwhelmed, the game features a handy game-pausing feature that allows the player to examine the battlefield and re-assign instructions to team-members as necessary.

As implied earlier, the graphical designs in Freedom Force are highly influenced by the artistic styles in comic-books of the 1980s. As such, there is very simple texturing in this game, in return for a very varied colour palette. This would have been charming, if not for the lighting of the game, which does not give the models in this game the vibrancy that they need in order to look like they have come from a comic-book than simple 3D-design software.

(To give the lighting system the benefit of the doubt, Freedom Force was made before the optimization of bloom and HD graphical technology.)

Furthermore, the animations of characters' faces are not very satisfactory. Of course, at the time, digital graphics that were efficient enough for electronic games on the PC platform were still not good enough to make lip-synching easy, so the less-than-accurate lip-synching would seem forgivable. Yet, the caveat is that the game repeats this lip-synching a lot for in-game cutscenes.

To offer an example, if a character gets angry during a conversation (or monologue) in a cutscene, the game calls up a portrait of the character's head to accompany the (voiced-over) text for these segment. Certain scripts are used to change the structure of his/her/its facial polygons to make the character look angry and, more importantly, have his/her/its mouth (if any is visible) yammering away. The game uses the scripts whenever said character is angry, and also the same scripts again when other characters are angry.

In other words, there is a lot of repetition of such discordant yammering in characters' portraits during cutscenes.

Other animations in Freedom Force are fortunately not as dubiously designed. The officially available set of animations are associated with the official characters, thus each of them is a visual representation of its associated character's unique personality. As long as these characters are moving at their default speeds, these animations look great.

However, when they are affected by speed de-buffs or buffs, the changes in their animations merely extend to decelerations or accelerations, even if the status effects should not be causing such visual changes, such as the "Stunned!" status effect which causes characters to suffer awkward slow-mo variants of their usual animation (in addition to losing their ability to attack and to move at reduced speeds).

Character models in Freedom Force also have surprisingly fluid animations for flying (for a game of its time). The transition between moving along the ground and taking to the air is very believable (as believable as flight-capable humanoids can be). Flying itself has the character taking on various postures or stances that are more than just having one arm ahead of one's head a la Superman.

Characters that are airborne for other reasons, such as being knocked or thrown about, have animations that show them careening helplessly. There are also animations for having them hit something, with these usually changing the orientations of their models according to impact angle. Being knocked around also has gameplay ramifications because these characters suffer impact damage for every surface that they hit; successive hits will eventually knock them out.

Without resorting to the importation of custom animations, the player won't be able to create custom characters without having them share animations with the official characters. Considering that the game is accommodating to imports, this is a minor complaint, but it would have been more convenient for players if the character creation system also includes the tools to alter animations in-game.

Most environmental objects are static things, or have repetitive animations, as befitting inanimate objects that are supposed to either sit still or perform menial tasks. Most of them are appropriately mundane as they should be, though some do benefit from the comic-book themes in this game by having outlandish models and animations, such as the contraptions that belong to typically evil mad scientists.

Outdoor levels in Freedom Force are bounded by black, featureless skyboxes, which can cause some disbelief; a disappointing example is that roads in a city block may lead to the edges of the map, and simply end there, cut off by utter darkness. However, Freedom Force also has some levels with believable boundaries and very impressive skyboxes, namely those that occur in the finale of the campaign. Describing these levels would constitute a spoiler, so it suffices to say that these levels will more than compensate for any disappointment of seeing levels that appear to exist in the middle of a void when they are supposed to have some appearance of physical continuity with the other parts of the world that the Freedom Force protects.

Another issue with the levels is that there is no mini-map. Some levels are far from being collations of linear paths, especially those set in the city that have so many alleyways for quick shortcuts and for the game designers to hide Canisters in. The game does allow the player to practically scroll all over the map (usually to locate Canisters) and use hotkeys to automatically reorient the camera on his/her team, but having a mini-map would have been a lot more expedient.

As a game with themes of Bronze Age comic-book themes, there are plenty of exaggerated sound effects to be heard in Freedom Force. Hits on enemy characters produce aurally satisfying wallops and environmental objects break most noisily as they should when they are blown apart by super-powered collateral damage. Powers often come with sound effects too, and these range wildly from ominous drones of energy beams charging up and the whoosh of fireballs burning through the air to the warbling of psychic assaults and the ticking of unseen clocks that accompany powers that bend time. Every sound effect of these sorts is accompanied by cheesy onomatopoeic text, which can be very amusing to those who remember the Bronze Age comic-books fondly. (They can also be turned off, if the player does not appreciate the intended charm of these.)

Conveniently, status changes are accompanied by audio cues, such as a brief suspenseful tune when a character is afflicted with the "Fear" status (which has the victim running away from the battle), if the text cues are not enough to alert the player to them already.

The levels in this game may be mostly static, but some ambient sounds give life to them, such as car-horns honking in city-based levels and the howls of arctic winds in winter-afflicted maps. Fortunately, these do not have textual cues.

The voice-acting in this game are mostly composed of the dialogue and monologue in the story campaign, though characters also have plenty of quips and utterances when ordered about and when they engage in battle. As to be expected from characters whose designs are inspired by the outrageous and sometimes whimsical characters from the Bronze Age comic-book era, their lines have plenty of puns and campy wit. Again, this would be very pleasant to players who are/were fans of this era.

The soundtracks in this game have their composition taking a leaf from the animations in the '80s, though the bulk of them are not necessarily of the kid-friendly Saturday-morning-cartoon variety. Instead, most of them are reminiscent of those that accompanied political propaganda and fictional tales of suspense in the '80s. This is not a coincidence, as the campaign in Freedom Force has themes of the '80s that were more serious during that time, such as anti-communism and espionage of the political and industrial sort. The soundtracks are especially prominent in the comic-book cutscenes, where there is little else other than the voice-overs to make up the aural portion of these.

The multiplayer segment has the player-participants taking their own four-person squads into the map chosen for play, according to the PP limits set by the host. Unfortunately, the only match mode is team deathmatch, which is disappointingly simple. Considering that the game came with character creation tools, it is odd that the game-makers did not include level design tools as well. Freedom Force's multiplayer would have benefited greatly from maps with custom-designed scenarios, like those in the story campaign. Nevertheless, the bulk of the fun to be had from Freedom Force is its campaign mode.

In conclusion, Freedom Force may be using thematic designs which are from an era long-passed and whose immediate appeal will only be apparent to those with fond memories of this time, but underneath its exterior is a great set of mechanics that govern the gameplay of having super-powered individuals causing mayhem - righteous or otherwise.