INTRO:

It is not very often that an enthusiast of anthropomorphic animals would aspire to create a video game without corporate backing, much less actually achieve this ambition. Therefore, Dust: An Elysian Tail would come as a pleasant surprise, especially to players who want to see a video game with furries in it but without it having the label of a game-making giant (e.g. the Ratchet & Clank series).

Dean Dodrill has lofty ambitions, that much is certain. He has an ongoing project for an animated film since 2003, yet to be completed. It was perhaps a surprise (likely to himself too, if his blog posts are to be believed) that this project would create a by-product when he decided to return to the programming skills which he had learned before. The result feels far more than just a mere by-product though; it is deserving of recognition as a fully-fledged work of fiction.

Unfortunately, it is affected by some issues in its presentation, some of which are brought about by people whom Dodrill works with.

PREMISE:

Although the deliberate malapropism in its title (that is, using “tail” instead of “tale”) may suggest that the writer is not exactly one who would impress jaded story-goers, Dust: An Elysian Tail does have an intriguing tale which is worth following – if one could stomach some of its shortfalls.

It utilizes many tropes, some of which are quite well-worn, but it is also aware of them and lampshades them for some amusingly awkward moments.

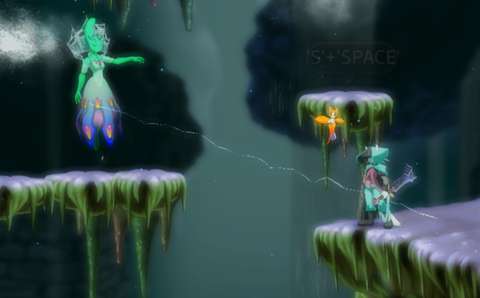

Anyway, the player character is an amnesiac vagrant of sorts, one who gets the simple name of “Dust” by a cruel-looking but surprisingly kind-hearted sword which flew into his hands in the prologue. To make matters even more bewildering to this already confused guy, he is subsequently introduced to another flying entity, this one a diminutive creature who alleges that she is the “guardian” of the sentient sword.

This can seem to be a wild story which makes use of many mysterious set-ups to flesh itself out with, but though such prologues have been done many times before, it would take a very poor writer to screw it up. Fortunately, Dean Dodrill and fellow writer Alex Kain are not very poor writers.

Of course, one could argue that the story of the game is yet another story of redemption and revenge, but the tropes in the main story are twisted in ways which jaded story-goers would find a bit impressive.

Unfortunately, planning a story is not the same as executing it though. Although Dodrill’s competence at writing is difficult to question, the calibre of most of the people who deliver the lines for the characters in his story is not.

PLOT-HOLES:

The story of the game is not without some plot-holes. The writers had realized the presence of some of these and patched them over with some convenient plot-twists, but some of the patches are not convincing.

For example, there is no explanation for how the sword has a guardian. Perhaps this would be reserved for the Elysian Tail movie; indeed, if one is to be apologist for the game, many unexplained loose ends of the story can be said to have been probably reserved for the indie movie, or perhaps the next game, if Dodrill is interested in it.

Another example is the unlikelihood of a certain civilian character being able to beat a battle-hardened warrior. The writers attempted to patch this over by having another character imply that the latter had been arrogant to the point of being careless, but this implied mistake was never shown in a manner which is more convincing than just someone else’s words.

There are more than just this example. These other plot-holes will be mentioned where convenient later in this review, because they happen to affect other aspects of the game.

Another remark which has to be made here is that some of the promotional material for the game, especially the posters and box-art, suggest things about the story, but in truth, most of these suggestions are not even seen implemented in the story. This can give an impression that some of the plot-lines of the story has been changed ever since Dean Dodrill created those artwork materials.

SIDE-SCROLLING:

Being an indie game, it would not be a surprise that the game makes use of a 2D landscape. The character mainly moves along a plane and at different heights.

If there is any amusement to be had from this design, it is that it is perhaps lamp-shaded a few times in the game. For example, there is a town with townsfolk who mention that their town has two sides.

MOVEMENT:

As Dust’s appearance would suggest, he moves about with great alacrity.

Initially, he can only jump, move around from side to side and drop down from one (floating) platform to another below. Veterans of 2D platforming games would be familiar with such controls.

However, said veterans might raise their eyebrows at how the game introduces Dust’s other moves. Instead of setting up scenarios where Dust naturally has to use them, the player must collect magical orbs to unlock Dust’s other moves – even if he seems to be able to use them without magic to gain the potential to do so. There is also no convincing narrative-oriented reason for the presence of these orbs, or why he could not make such moves in the first place.

For example, Dust cannot make sliding moves initially, even though one would think that such a nimble person as he would be able to do so. Instead, he must collect a certain orb in a certain subterranean level to be able to start sliding around.

At least some other moves appear to require the use of magic. For example, Dust’s double-jump appears to be viable because of a pair of ghostly wings which sprout from his back (or hips; it is not always consistent).

(Interestingly, where other platforming games introduce double-jumping quite early on, Dust: An Elysian Tail introduces it very late into a playthrough.)

Regardless, it is the player’s interest to unlock more movement methods for Dust, because they are needed to progress in the game and discover secret areas; they are also very convenient for simply evading enemies. Unlocking them is a matter of following the story, conveniently.

Part of the game’s appeal is remembering places where the player cannot reach at the time or where there are clues of such places. Returning to them and using Dust’s unlocked moves can give vibes of Castlevania and Metroid, which might entertain people with fond memories of these classic games’ gameplay.

ATTACKING:

Dust is armed from the get-go, but only ever has the talking sword as his weapon. However, the weapon is very much suited to Dust’s agile fighting style, something which the player would learn early on. The sword’s diminutive guardian also has some tricks of her own to contribute to combat.

There are generally three categories of offensive moves against enemies: melee combos, Dust Storm and Fidget’s cantrips. Not all of them are of satisfactory utility, however.

MELEE COMBOS:

Melee combos, or the stringing up of default attack inputs and alternate ones in specific sequences, are the first category of offensive moves available to the player. In fact, all of the combos in the game are listed down in the in-game documentation, and can be used from the get-go.

Unfortunately, the greatest appeal of combos is watching Dust’s animations. In practice, they are the riskiest offensive moves to use.

Combo sequences, when entered correctly (and this is easy to do), reward the player with increased damage with each subsequent move after the first; the finisher is typically the most painful to whoever is on the other end of the sword. Melee combos also refill Dust’s energy reserves, the uses for which will be described later where relevant.

However, the player must put up with the lengths of some of the animations for these moves; these animations do not have invincibility frames, and not all frames can be cancelled out of. Sword-swings, in particular, cannot be cancelled.

Coupled with the consideration that Dust’s melee combos are obviously all close-combat-oriented and that there are many, many enemies in the game which use melee attacks, melee combos can be risky. This is very much so at the higher difficulty settings, especially Hardcore, where getting hit is costly. Furthermore, at the higher difficulty settings, there are more enemies which attempt to get behind Dust’s sprite, thus putting him at risk of being attacked from the rear when performing melee animations.

Therefore, it can be said here that melee combos lose a lot of their utility as the challenge ramps up. Furthermore, they are just not as efficient as the other two categories of offensive moves, either at racking up a hit combo-counter (which is not to be confused with melee combos) or at actual combat.

Melee combos do have the side benefit of refilling Dust’s (and Fidget’s) energy reserves, but there is a far less riskier – and much cheesier – way to regain energy, as will be described later.

DUST STORM:

Despite being a misnomer (albeit a cool-sounding one with significance which becomes clear very soon), “Dust Storm” is an easily appreciable combat move.

There are two variants of Dust Storm. The first and default variant has Dust twirling the Blade of Arrah; this creates a vacuum of swords which sucks in nearby enemies of sizes comparable to Dust’s. Understandably, this is unpleasant for them.

However, this variant of Dust Storm has many drawbacks. The most obvious of this is that Dust stays still, which is not always desirable when he is almost always outnumbered by enemies. This variant of Dust Storm also does much less damage per hit than melee combos and, more importantly, less damage than the other variant.

These setbacks severely reduce the utility of this variant of Dust Storm.

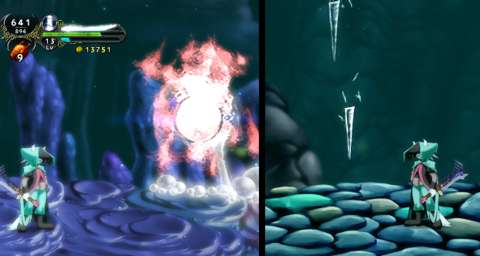

The other variant, simply called “Aerial Dust Storm”, is far, far more reliable and tactically useful. Fortunately, Dust learns this very early on, and adroitly astute players may find themselves using Aerial Dust Storm more often than not when in combat, and even outside of it.

Aerial Dust Storm is executed by chaining a jump together with the input for Dust Storm. This can be done as soon as Dust starts his jumping animation, so this means that Aerial Dust Storms can be executed close to the ground.

In fact, a twitchy player can have Dust hugging the ground, thanks to the Aerial Dust Storm’s targeting mechanism, which will have to be explained in its own section later.

The common side effect of both Dust Storm variants is that they can suck in most loot-drops from enemies, even from far away. However, getting them to come into contact with Dust’s sprite is a bit tricky, because they will orbit around his sprite. (Aerial Dust Storm is, again, better at doing this.)

The common drawback of both Dust Storm variants is that Dust has limited stamina with which he can perform it. His sprite glows red as his stamina runs out; when it does, he takes damage (except at the Easy difficulty setting), stops his Dust Storm and appears to suffer from knock-back. Dust’s stamina reserves cannot be upgraded in any way, either.

However, this drawback can be used to the player’s advantage, as will be described later together with a nuance (or rather, exploit) concerning healing items.

Both Dust Storm variants are intended to be used together with the third category of offensive moves, which will be described after the targeting of Aerial Dust Storm.

AERIAL DUST STORM TARGETING:

When Dust is performing his Aerial Dust Storm, the player is given control over the direction of his dervish twirling. However, the controls behave differently when there are enemies nearby, and even more differently if there are floating or flying enemies.

If there are no enemies nearby when Aerial Dust Storm is executed, the move follows the effects of gravity; Dust will eventually fall, thus following a parabolic trajectory. This is the case even if enemies come into view.

However, if there are ground-based enemies beneath Dust when Aerial Dust Storm is executed, the effect of gravity can be suspended if the player has Dust changing directions rapidly.

With this peculiar physics loophole and the Dust Storm’s huge hit-box, the player can use Aerial Dust Storm to deal with large enemies such as giants. Moreover, because the player is always in control of Dust’s direction of movement when using Aerial Dust Storm, the player can have Dust moving away before he is hit by enemies.

If there are flying enemies (or ground-based enemies on floating platforms) far above Dust when Aerial Dust Storm is executed, the move disregards gravity. The player can even direct Dust such that he shoots up into the air for ridiculous distances.

There is an issue over how far the just-mentioned enemies have to be in order for this to trigger. The most reliable indicator is that the camera pulls back to give the player a larger view of the action, but this can also trigger at other times seemingly randomly, causing Dust to shoot up into the air and leaving the player to guess where he would land.

FIDGET SPAM:

The sword’s diminutive “guardian” has magic of her own, and is more than happy to use it – even if it is very weak by default.

When triggered as is, Fidget’s magic barely harms enemies, even when the player has upgraded her magic. (This is mainly because the opposition becomes more powerful as new enemies are introduced. If there are anything which can be hurt by Fidget’s default magic, they are monsters which the player has far outclassed.)

However, when Fidget’s magic is channelled through either variant of the Dust Storm – and this is done automatically if Dust is using Dust Storm – it becomes dramatically more powerful.

Indeed, there is practically next to no incentive to use Fidget’s magic in its default form. One would wonder whether it was purely included in the game for comic relief, especially considering that it consumes the same amount of energy as its amplified form does.

Initially, Fidget starts with magic that can be best described as magical missiles. These flit about, passing through enemies and damaging them rapidly; its amplified form, a cloud of the same missiles, is most efficient against very large enemies.

Fidget gains two other types of spells later, to a total of three. The second spell is the obligatory fireball spell. When amplified, each fireball ends its flight within the ground, which then explodes to release a fiery geyser which inflicts tremendous rapid damage. However, considering that the geysers do not move, this spell is only efficient against slow or immobilized enemies.

The lightning spell is generally the most effective and efficient of the three, if only because it immediately and automatically hits any enemy that is in the vicinity when it goes off.

Spamming Fidget’s magic in its amplified forms is often the best way to deal with enemies, most of whom resort to close-combat. Besides, Fidget’s magic is the only convincingly ranged offensive option which the player has.

However, it draws from Dust’s “energy” reserves, which also happens to be used for dashing. The player will notice that he/she runs out of energy quite often if he/she has Fidget spamming, but there are ways to regain energy – including a cheesy one.

DASHING & SLIDING VERSUS AERIAL DUST STORM:

Dashing and sliding are both evasive manoeuvres, but where dashing consumes energy which could be (somehow) used for Fidget’s magic, sliding is free. Of course, sliding can be only be done when Dust is on solid ground, whereas dash can be used in mid-air too.

Both moves can be used to cancel out of melee combos and Dust Storms, though sliding cannot break out of Aerial Dust Storm, obviously. Dashing also grants invincibility frames, whereas sliding merely shrinks Dust’s hit-box for the purpose of determining whether he gets hit. On the other hand, Dust gets to trip enemies when sliding under them.

However, both sliding and dashing put Dust into animations which, ironically, cannot be cancelled out of. The player can have Dust getting into an even worse position if he/she had not given thought to where he would be when the animations stop.

Aerial Dust Storm, on the other hand, is completely within the control of the player, thus making it more reliable for escapes – especially when it can be used to transition from going on the attack to tactical withdraw in a heartbeat.

Furthermore, Aerial Dust Storm consumes stamina instead of energy, so it can be coupled with Fidget’s magic at any time when the player still has some of both.

PARRYING:

The last, and unfortunately least, option for combat is parrying.

By timing an attack with an enemy’s, or holding down the attack button for a couple of seconds within an imminent strike from an enemy, Dust can block the attack of his enemy. Both combatants would be momentarily staggered, but Dust is generally the faster of the two to recover; Dust also appears to benefit from invincibility frames as this happens, and time slows down enough for the player to decide on what to do next.

Certain enemies are dazed from the ordeal, which opens them up for attack; they happen to have much reduced defence when in this state. However, not all enemies are dazed, especially those which appear to be martially skilled.

This very selective and situational effect of parrying reduces its utility.

Perhaps the most useful benefit of parrying is that Dust’s energy reserves are somehow immediately refilled by the act of parrying. However, refilling energy reserves in this way is relatively risky when compared to another method which is associated with healing items, as will be described later.

REMARK ON FALLING:

An astute player who has been frequently using Aerial Dust Storm or height-gaining movement methods quickly notices that Dust does not suffer any damage from falling; he will always lands on his feet while falling down, supernaturally skilled as he is.

This unbelievable peculiarity is itself highlighted in one particular moment in the game concerning one-way trips.

INVINCIBILITY FRAMES:

In addition to aforementioned scenarios where invincibility frames are granted unto Dust’s sprite, there are other instances where this happens.

Dust is not a heavy-set guy, so his lithe frame can get knocked around for quite some distance when he is hurt. Fortunately, Dean Dodrill is aware of how annoying constant knock-backs and knock-downs can be, so knock-backs and knock-downs happen to grant Dust a generous number of seconds worth of invincibility frames.

Getting hurt by environmental hazards also grant a few seconds of invincibility frames to Dust, but only for the type of environmental hazard which hurt him. Nevertheless, this gives the player time to get out of the way before the environmental hazard re-applies its damage.

These are very forgiving game designs, which help make some platforming segments bearable, if the player knows how to utilize Dust’s escape moves.

HEALING:

As with most games, having Dust’s health drop to zero in this game generally means a trip to the loading screen. Therefore, it is in the player’s interest to keep Dust’s health meter close to full, or later on, have items which bring him back from death’s door.

There are very few methods of healing, so health is at a premium in this game, especially at the higher difficulty settings where some gameplay crutches are removed.

Firstly, there are healing items, which as their name suggests, heal Dust. Some healing items have additional properties; these usually come at the cost of a higher price or reduced healing compared to another purely healing item of similar price. There is a tertiary effect of healing items, which will be described later. The player can also turn on automatic use of healing items, which is convenient.

Next, there is the health granted by saving monuments. Getting Dust onto a saving monument refills his energy meter as well as some of his health meter, up to a certain point; higher difficulty settings has this point being lower. At the Hardcore setting, the saving monuments are all but useless at healing.

After that, there is regeneration. This is granted by gear items which generally appear at the 50% mark of the game. Ostensibly, the player could have Dust wait at a safe spot to heal over time, but this is not a good way to pass the time with. Furthermore, enemies do respawn eventually; this will be elaborated later.

There is a fourth way of healing, but this occurs together with an environmental hazard which will be described later because of how frustratingly fickle it is.

ENERGY-REFILLING EFFECT OF HEALING ITEMS:

Regardless of its amount of healing and its secondary properties, any healing item will refill Dust’s energy meter to full. This is an easily overlooked benefit.

This benefit means that as long as Dust is not at 100% health (which disables the use of healing items), the player can resort to using healing items to refill his energy reserves. This is far more reliable than using combos on enemies, parrying attacks, and, of course, waiting for the reserves to refill on their own.

There is the flip-side of not being at 100% health of course, but instead of having enemies attack Dust or getting Dust into an environmental hazard to hurt him, using the drawback of Dust Storm is a much more controllable alternative.

(This will not work at the Easy difficulty setting of course, but at this setting, any offensive tactic would work such that this exploit is unnecessary.)

This exploit also means that even healing items which have been superseded in terms of healing amounts can still be useful, if only as cheap sources of refilling energy. (This has been shown in an earlier screenshot.)

REFERENCES IN HEALING ITEMS:

In terms of their practicality, most of the healing items follow a path of progressively increasing costs and healing amounts. Some others diverge by offering buffs such as increased defence, but they also follow a similar path of progression. Gameplay-wise, they would not seem impressive to experienced game consumers.

However, their descriptions and sprite designs might just amuse where their gameplay designs could not.

The healing items which appear early in a playthrough might be pokes at tropes concerning healing items. For example, there is a deconstructive remark about fruits and their healing abilities.

Other descriptions have much more apparent references, such as a healing item which pays tribute to a running gag in the Castlevania franchise.

The next set of healing items appears to reveal the writer’s inclination towards Korean foods. Interestingly though, the last set of healing items are Western foods instead.

REMARK ON REVIVAL STONE:

The Revival Stone is a very expensive “healing item” of sorts; like its name suggests, it brings Dust back from death’s door and back to full health. When Dust’s health reserves surpass 2400, Revival Stones become increasingly more efficient as a “healing” tool because actual healing items have their costs pegged to their healing amounts.

This would have been a great nuance, if not for the fact that the merchant has unlimited supplies of Revival Stones. Hoarding them becomes quite a simple if tedious matter later in a playthrough, when money is not too difficult to come by, especially if the player has loot-drop-increasing items.

MAGIC BAG INVENTORY:

Conveniently, the game makes use of the trope of the “magic bag” for the inventory system; the player can stuff many types of items into the inventory at any amounts.

Interestingly, the writer is aware of this unbelievable convenience and makes no attempt to rationalize this, even with the deus ex machina story element of magic. Instead, he uses this as an opportunity to poke fun at this trope.

MYSTERIOUS MERCHANT:

Early on in the first chapter of the game, the player is introduced to a seemingly shady character who shrouds himself and has glowing eyes. He inexplicably sets up shop in all sorts of unseemly places in very small tents which are curiously overlooked by the otherwise hostile locals.

Despite his small tent - which would give him barely enough room to move about, much less stock wares - some of his wares have unlimited stocks. This is the case for most healing items. Items with limited stocks follow different rules on stocking though, as will be described shortly.

Furthermore, the player can have Dust interact with the merchant at any time to browse his wares – even when there are enemies nearby (they simply have their A.I.-scripting disabled).

This character may be the game’s indirect commentary on merchants in old classic games, in which such characters set up shop in unseemly locations which seem bad for business, yet their shops also happen to be safe havens.

On the other hand, the game does drop hints about the identity of the mysterious merchant and eventually provides exposition on him, though some questions about his unbelievable capabilities remain, of course.

ITEMS WITH LIMITED STOCKS:

The most prominent items with limited stocks are crafting materials. This is because the merchant does not stock any of these initially, simply because he does not know which of the local materials have worth as commodity. Thus, he needs help knowing which are which.

(Dust would not know either, but Arrah happens to know – by virtue of being an ancient sword with aeons of knowledge – so a plot-hole has been covered well with a convenience brought by an unbelievable character.)

As a reward for selling and thus showing crafting materials to him, the merchant gives a bonus on top of the selling price for a type of crafting material which he has yet to stock. Afterwards, he starts to stock it periodically, eventually building up stocks to certain numbers (which are different for different materials).

Buying crafting materials from the merchant is perhaps a more reliable way of getting them than killing monsters for them. Of course, the player needs money to buy them, but that is what killing monsters is for; money is guaranteed as loot-drops.

Then, there are gear pieces. These are limited in stock, and once they appear in the merchant’s store, there rarely is any restock for them. On the other hand, the player is far better off finding gear pieces from treasure chests or from crafting them, if only to make the former more fun to discover and the latter more useful. Besides, the merchant will not sell very powerful gear, which these other sources would provide.

The final notable limited-stock items are treasure keys (more on these later). Curiously, there are only ever several of these from the start of any playthrough, and they are never restocked.

CRAFTING:

A short while after obtaining crafting materials for the first time, the player would gain what Arrah calls “blueprints”. In practice, these are “incomplete” items which need crafting materials and some items to become complete, as well as the services of a blacksmith who does not appear to learn how to craft items by remembering the instructions from blueprints.

Unfortunately, blueprints cannot be sold off as they are. They can be turned into actual gear pieces, but the selling price of any crafted item is equal to the cost of crafting it. Therefore, the player is simply making a loss when selling crafted items, because he/she could not recover the materials which have been spent.

There may be narrative issues with crafting items too. Some of the items are described as items with legends of their own, and yet the player can craft them into being.

Anyway, the player would not come across the aforementioned blacksmith until a while into the game. Even after the player has found the tradesperson, getting to this person to obtain his/her services again can be tedious – a fact which Dust and Fidget would raise, though this peculiarity is countered by the blacksmith’s explanation about the locale for the forge.

Fortunately, the player can complete a side-quest to obtain the very appreciable convenience of being able to craft items on the spot. This convenience even allows the player to purchase crafting materials from the merchant through the blacksmith for no additional cost.

Speaking of conveniences, the game could have had the convenience of browsing the merchant’s wares on the spot without having to visit him. However, this omission was perhaps for the better, because it made the merchant’s tent a welcome sight and also prevents the game from being too easy to play.

MONUMENTS & WARP SPHERES:

Not long after the start of any playthrough, the player comes across mystical edifices which once belonged to a civilization of times long past. Their magic is still there to be utilized though.

The main function of these monuments is as save-points; the game does not make use of freer game-saving systems, for better or worse (depending on one’s perspective). Also, as had been mentioned earlier, they can help heal Dust to a certain point, depending on the difficulty setting.

The most appreciable design of monuments though, is their convenience of letting the player exit out into the world map, if only to re-enter stages at points where they are convenient. This convenience comes with a price though; this requires the consumption of Teleportation Stones, which are very rarely found and often have to be bought.

The game could have been better if the player can spend Teleportation Stones to teleport from one monument to another, but there is no such convenience. The player’s need to pass through the same levels over and over to track down treasure or secrets could have been negated if there had been one.

Warp Spheres are similarly ancient edifices, but they are usually meant for intra-level travel. Having the party going into one turns it into even more of a brilliant light show than it already is, followed by them popping out of another Warp Sphere on the other end of the connection.

REMARK ON MERCHANT AND MONUMENT PLACEMENTS:

Early in a playthrough, the merchant’s tents and the monuments are often placed away from each other and sometimes in different levels; the merchant’s tents are usually fewer in number than the monuments. This means that resupplies are not convenient to perform, but the game does make itself more forgiving by having more generous placements of monuments.

There are a few occurrences where there are strings of levels without any monuments or merchant tents, which can make for gruelling experiences the first time around if the player has not already forewarned himself/herself with third-party guides. There are few in-game warnings about such stretches.

Both merchant tents and monuments can be within the same level, but there is a noticeable trend about the distance between them. Early on in a playthrough, they are often far away from each other, with the tent often tucked away in a nook. As the player progresses though, the distance between them becomes closer – which is appreciable, because the challenges become greater and going through a stretch of powerful enemies to go from one to the other would have been a slog.

GAINING LEVELS:

Implementing some kind of experience and level system is a reliable – if rather old – technique of giving some sense of development in the player character, even if this development is hardly narrative-related. Dust: An Elysian Tail would not forgo this unexcitingly “safe” gameplay element.

Dust gains experience points from many sources, the main one being the deaths of enemies; the other sources will be described where relevant.

Reaching an experience threshold grants a “level” unto Dust, as well as one point to go into his few and typical statistics, which include the self-explanatory “Health” and “Defense”. The “Attack” statistic influences just Dust’s melee combos, whereas Fidget’s magic and the efficacy of Dust Storm is influenced by the “Fidget” statistic. (This oddly named statistic is explained in its in-game description.)

GEAR PIECES:

The gear which Dust can use would seem to be familiar fare to experienced players. There is a slot for “augments” to the sword, which practically works like a weapon slot. There are slots for armor and jewellery too. The gear system is functional, but otherwise not remarkable.

It has to be mentioned here that Dust: An Elysian Tail may have an imbalanced system concerning the defence statistic. The defence statistic applies its effects as a straight unmodified reduction to incoming damage, so if the player focuses on upgrading Dust’s armor and increasing his Defence, it can make a mockery of early-playthrough enemies, even on the Hardcore difficulty setting.

HIT COMBO COUNTER:

To prevent confusion with “melee combos”, the gameplay element in this game known as “hit combo” would be called “hit combo counter” instead in this review.

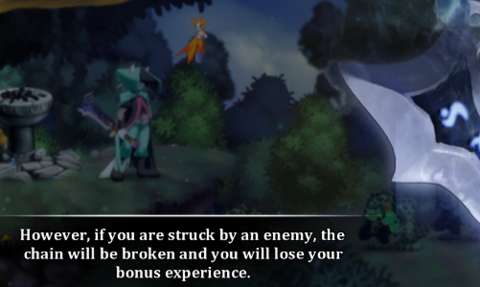

Whenever either Dust (through his melee attacks) or Fidget (through her magic) lands a hit, this occurrence contributes to a counter; as long as the player can keep attacking enemies within a few seconds between each hit, the counter will keep increasing.

This can be exhilarating, if only because the game emits aural flourishes whenever the counter breaches certain thresholds. However, the counter resets if Dust is damaged in any way.

The counter also ends when the player is no longer able – or willing – to maintain the counter, e.g. when there are no more enemies nearby. However, this occurrence is accompanied by the granting of bonus experience at an amount equal to the counter when it ended.

However, gaining experience in such a manner is less efficient than killing many enemies as quickly as possible and repeating after they respawn.

There does not appear to be any other noticeable benefit to racking up a high hit counter beyond the bonus experience, a certain side quest and (of course) achievements. It may influence the quality of loot drops from enemies, but racking up a high counter is a very chaotic endeavour which makes such an observation quite unreliable.

BUFFS & DE-BUFFS:

As mentioned earlier, some healing items grant buffs onto Dust. These buffs are depicted on-screen via icons which appear over and to the left of Dust’s sprite. They can be a bit difficult to see in the heat of battle though.

De-buffs have much clearer visual indicators. For example, getting Dust poisoned causes his sprite to be given a green tint and flash as he takes damage periodically from the poison. As another example, Fidget’s sprite becomes obscured by a black fuzz when she is silenced.

However, the game will not provide special visual indicators for buffs and de-buffs which are granted by gear pieces. Items with regeneration bonuses do show what they do, but they piggy-back on the system of visual indicators for healing.

STAGES:

The locales in the game are organized in ways which are best described as “stages”, to make use of an old term which was once used to described classic games with. This is perhaps fitting, because Dust: An Elysian Tail is influenced by old classic titles.

These locales have their own local inhabitants (civilian and hostile), (usually) their own set of environmental hazards and sometimes their own sense of verticality (or lack of it). There are usually enough practical differences between the stages to give an impression that they are more than just cosmetically different. Exploring them for the first time can be quite entertaining, especially if one is interested in the game’s artwork.

Going through them for the second time is not as fun though. This is in part due to the map system for the stages.

The map system is a tribute to the Legend of Zelda series, but such a map system is best left in the past due to how poor it is at informing the player of what is up ahead.

To elaborate, the map system presents the levels within a stage – and they can be of very different sizes – as a grid of squares. Broken borders show that there are connections between adjacent levels at a direction as specified, but not the number of connections; there is usually just one in each direction, but this is not always the case. More importantly, it does not indicate the presence of environmental hazards and the types of obstacles which the player would face.

Furthermore, the map system also does not show door-based connections.

(Door-based connections have the player entering another level not through the edge of the previous level, but obviously through a door, cave entrance or similar edifices. Such connections are used for both mandatory level transitions and entrances to secret areas; the former are generally more obvious.)

Fortunately, the map system does at least inform the player of the presence of very important things, namely monuments and the merchant’s tents. It also shows which levels have treasures/secrets and which already have these plundered.

TREASURES:

Speaking of treasures, these are intended as yet another tribute to old classic titles which reward exploration –and backtracking – with goodies.

These goodies are stowed away in ornate strong-boxes, which would seem too peculiarly huge to be considered typical “treasure chests”. These containers are usually either at hard-to-reach places or in easily-overlooked nooks and crannies; meticulous players would have no issues finding them.

For better or worse, even after the player has spent the effort to look for them, the player is subjected to a mini-game, specifically one involving the pressing of buttons according to on-screen prompts before time runs out (which is depicted with a huge visual indicator of some device grinding on a rail).

If the player “wins” the mini-game, he/she expends a treasure key and opens the treasure chest. If he/she fails, he/she does not lose the treasure key, but has to try again; the button sequences are different every time.

The goodies from treasure chests are mainly either a lot of cash or a lot of healing items. However, each treasure chest also contains a particular item which the player might want or might consider junk, depending on his/her playstyle. This item may be a gear piece, Revival Stone (or a clutch of Teleportation Stones) or a blueprint.

A player who has been grinding a lot to either gain levels or obtain money or materials for gear upgrades would find these quite worthless. For players who had not been doing this, they are usually worthwhile, but only if they backtrack whenever they can to get to previously unreachable treasures as soon as they obtain the means to do so.

Some treasure chests do not contain treasure, but rather unpleasant surprises in the form of a large mob of monsters which had somehow gotten themselves trapped in them - and survived the ordeal. (This may be a reference to the trope of “monster closets” or something similar.)

There are often no warnings of such chests, at least not without third-party guides. Fortunately, the player is refunded with treasure keys from these chests.

FLOATING TREASURE KEYS:

Interestingly, treasure keys are used as treasures themselves. More often than not, they are placed tantalisingly in the player’s view, especially early in a playthrough, thus causing completely fresh players some frustration before they realize that they need to have Dust learning some new moves before they can be obtained.

Other keys require the player to perform some acrobatics. Yet others are easier to get, though they may be suggesting something, like the one in the following screenshot.

ENVIRONMENTAL HAZARDS:

Arguably, the environmental hazards which Dust would come across are more dangerous than the enemies which he would encounter.

As mentioned earlier, Dust is immune to fall damage. However, he can still be damaged by running into hazards. These include hazards which are pervasive in the platforming genre, such as the obligatory spikes and lava streams. Being hurt by these particular hazards can be especially painful – which is a fitting punishment, considering that they are the most obvious hazards and should have been quite easily avoidable.

In fact, these hazards hurt even more than enemies do. For example, where a heavily upgraded Dust may be able to take dozens of hits from enemies, he will never be able to run into spikes more than a few times.

Then, there are less avoidable hazards. There are icicles which fall down from frozen caverns and magical fungi which spill sorcerous fluids.

There is a design problem with these hazards. The sword would warn Dust that they are triggered by proximity, and indeed, this is at least partially true; they only ever trigger if Dust is nearby. However, they do not have any predictable triggering patterns, and appear to have completely random triggering rates.

This is especially so for the magical fungi, which can splash in rapid succession. That they sometimes splash healing fluids instead of harmful ones make them seem even more fickle.

An observant player would notice that these hazards are best avoided with dashes and slides, but this is more reliable for icicles, if only because they fall from the ceiling and thus give the player split seconds to dodge them. Magical fungi are, unfortunately, set closer to the ground and require aerial dashes, which are much more difficult to pull off.

There are more innocuous hazards, such as floating platforms which crumble shortly after Dust steps onto them, but which magically rebuild themselves a while later (conveniently enough).

Whenever the player comes across a hazard for the first time, the game introduces it in small numbers so that the player may practice and experiment with them, if he/she bothers to do so.

“FRIENDS” & SECRET AREAS:

Dust: An Elysian Tail makes tributes to certain other platforming-oriented indie games, though these would not be satisfactorily amusing to everyone.

Early on in a playthrough, the player would come across a cage with several locks. The locks have to be unlocked by several treasure keys, which can seem a lot, but the contents are worth the cost, even if the player is not amused by the cameos which subsequently occur.

These cages release characters from other indie games, most of whom have been redrawn by Dodrill but still resemble the originals.

They are called “friends” in-game, but if the player is hoping that they would actually help Dust fight or otherwise travel around with him, he/she would be disappointed. They are practically nothing more than trophies.

Further reinforcing the impression that they are little more than trophies, they gather at the stage known as the Sanctuary, frolicking around mindlessly.

Rescuing these “friends” does grant health bonuses, so they are not a waste of time. Speaking of them not being a waste of time, the experience of actually getting to them might just be more entertaining than releasing them. Getting to them often requires the player to have already unlocked many moves for Dust, or gained enough pass-card-like items to go past certain obstacles, in order to access places which are far away from the path which the player needs to take.

To elaborate, these characters are usually found in places which are associated with their games. For example, the Spelunker from Spelunky is found in a rather secluded cave. To cite more examples, the protagonists from the Dishwasher Samurai franchise are found in indoor places with rather depressing colour palettes.

Some of these places happen to be given more attention than the others. Chief amongst these is a certain secret which applies a filter to the visual display and splits the screen into initially bewildering segments.

SIDE QUESTS:

It would not take long for a seasoned story-goer to recognize the tropes in the story-writing of Dust: An Elysian Tail; one may even predict the ending quite accurately one or two chapters into the game.

Fortunately, where the main quest might seem unremarkable to jaded players, there may be some amusement to be had from the side endeavours.

This may not seem so initially, because most side quests are little more than fetch quests and backtracking trips. However, the remarks which their associated characters and the protagonists make, or even the name of the quest, might just make these chores seem more worthwhile, even if the player cares little for the more practical rewards (i.e. experience and money).

For example, there is a quest which has Dust and a boy having a fourth-wall-breaking conversation about the hit combo counter. The name of the quest also references Killer Instinct and the hideous Internet meme which it started.

Most of these remarks about the side quests are made by Fidget, who does the most lamp-shading in the game. Players who are annoyed by Fidget’s commentary antics might not be amused, but players who like the panning of tropes might just appreciate Dodrill’s sense of humor - even if the game is actually having the player go through the usual motions of typical side quests.

ENEMIES:

There are many enemies in the game. Most of them are quite different from each other, but there are a noticeable number of palette swaps too, especially the feral anthropomorphic lizards and their reptilian allies.

Enemies which the player has slain in a level are eventually replaced. If the player leaves an area within a level and returns to it after a long while, the enemies there would be respawned. Furthermore, all enemies within a level return when the player leaves it and comes back later.

The only exception to such rules is when the player stays within an area; Dust’s presence will suppress the scripts for nearby enemy spawn spots. This is useful for tough platforming sequences.

A meticulous player can exploit these respawn scripts to grind, especially the latter sort of scripts involving leaving and re-entering levels.

Whichever enemy the player would encounter, it is more than likely to be introduced in less harsh circumstances. To elaborate, when a new enemy is encountered for the first time, it is usually on its lonesome and it is in a place with few environmental hazards. It is up to the player to spend time to observe this new enemy and experiment with it.

Most of them can be lumped together in a few categories according to their behaviour and level of challenge.

There are the grunt-like mobs, which on their own, are quite easy to remove, specifically with melee combos. This is because most of these mobs have slow animations which can be interrupted with melee combos. Once they have been staggered, they can be juggled about either with melee combos or Dust Storm.

Some of these mobs may have smarter variants, such as those with jumping abilities. At the higher difficulty settings, these more often than not attempt to get behind Dust’s sprite, almost to a predictable fault. Then, there are tougher variants, such as the zombies in the obligatory undead-themed levels.

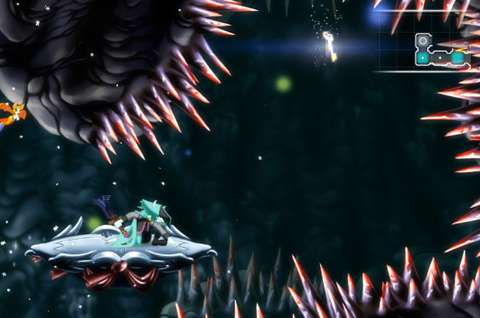

Later, the game introduces flying enemies. These practically move through obstacles, making them rather dangerous enemies because the player cannot rely on the terrain to herd them into a chokepoint.

The few types of flying enemies in the game are quite different from each other. For example, the first to be seen is little more than a flying grunt, but the next one spits acid and the one after flings electrical bolts which silences Fidget. However, all of them are generally easy to destroy with rapid wiggling of the Aerial Dust Storm.

After these, there are the obligatory bruiser archetypes. These are typically huge, and they have attacks which are difficult to interrupt and better off evaded. On the other hand, their sprites are immense, making them easy to hit, especially if one targets the tops of their heads with Aerial Dust Storm.

That is not to say that the enemies in this game are completely run-of-the-mill. Some of them can be a surprise, such as a slimy creature which is inimical to tactics involving jumping.

All enemies impede Dust’s movement. In the case of regular-sized enemies, they slow his running down; bruisers simply block him. However, dashing and sliding can be used to get past them; Aerial Dust Storm is also viable, and perhaps even better since it sends Dust up and over most enemies.

BOSSES:

There are boss fights in the game, which is to be expected of a game that pays tribute to old tried-and-true game designs.

Some of these boss fights are against enemies which are not plot-centric. These fights usually introduce the player to particularly troublesome enemies. For example, when the player encounters martially trained enemies for the first time, they come in a squad, which can make for quite a fight if the player does not recognize their limitations quickly.

The main boss fights usually concern plot-centric characters. As to be expected of such enemies, they are especially tough enemies, usually with their own unique capabilities. Learning to overcome their strengths can be entertaining for a while, at least until the observant player notices that Aerial Dust Storm and Fidget’s magic are generally the most effective tools against them. Staying away from them whenever necessary also tends to be a priority too, because each of them has powerful uninterruptible melee attacks.

A couple of the main boss fights happen to involve environmental hazards too. These make the fights a lot more difficult. However, more adroit and patient players would eventually figure out the least risky tactics to defeat them (and these tactics are likely to involve Aerial Dust Storm to quickly get around too).

DOLES OF REFERENCES & LAMP-SHADING:

If it has not been mentioned already, the game has plenty of references, mostly to other games. If it is not doing this, then it is lamp-shading tropes in video game designs.

There can seem to be a lot of them, perhaps to the point of being obnoxious. Furthermore, most of these involve Fidget’s remarks, which do not bode well for the player’s regard of her. In fact, it would be a rare player indeed if he/she had not wished that Fidget would just refrain from making a reference for at least once.

Of course, the true culprit here is Dean Dodrill and his eagerness to pay tribute or poke fun at games which he likes.

CHARACTER DESIGNS:

Other than the enemies which mainly serve as sources of danger for the player, there are characters which actually have lines to deliver, usually about the story, side quests or simply their personal motivations.

If the player has little interest whatsoever in the characters in the game, then there is at least the experience reward for meeting other characters for the first time.

(However, the game could have informed the player that “meeting them for the first time” is defined as voluntarily talking to them for the first time; encounters through in-game cutscenes do not count.)

For jaded players, their lines may seem to be the unremarkable staples which have been seen in so many other games with side quests. These include the usual expressions of gratefulness (or lack of it) and pleas for help and such other aid which, of course, only the player character could provide.

If they are not delivering these lines, they are spewing melodrama together with well-worn expressions. Chief examples of these include exclamations which the player would expect from stereotypical American country bumpkins.

Fortunately, some characters do deliver some amusing lines, such as a deconstructive statement about an idiom, which is quite silly when taken literally instead of metaphorically.

The most prominent characters are, of course, the protagonists. Unfortunately, the titular character might just be the least entertaining of the three, mainly because of the exaggerated performance of his voice-actor and partially because some of his lines are melodramatic.

Fidget may be a persona who brings to mind game characters who were particularly infamous because of their unwittingly annoying personality, such as Na’vi from one of the Legend of Zelda titles. A more tolerant player would not have much issue with her personality of course, but as mentioned earlier, she makes a lot of references and lamp-shades.

Even if the player does not find these too obnoxiously frequent, these clash with her character background. To elaborate, for a character who supposedly lived a life of seclusion with her clan before having to chase after the sentient legendary sword, she breaks the fourth wall with these remarks so often such that the player might just disregard her backstory.

Arrah the sword would be the most interesting of the three, if only because it seems particularly knowledgeable for a talking sword. Also, unlike so many other examples of sentient weapons which came before it and which established the character trope, Arrah is soft-spoken and diplomatic.

VOICE-OVERS:

For better or worse, part and parcel of the character designs are their voice-acting performances – unfortunately, they could not be considered exemplary so easily.

At the very least, the game makes a good first impression with regards to voice-acting by starting off with the narrator and the talking sword, who at least have fitting voice-overs.

However, as soon as Dust is introduced, the voice-acting goes downhill from there.

Much of the voice-acting is tainted with melodramatic and rather forceful performances, most of which are unfortunately delivered by Lucien Dodge, who is the voice of Dust and a couple of other important characters. (It has to be noted here that Dodge’s portfolio is mostly dubbing works for Japanese-designed games, and the English dubbing for these games generally could not be considered stellar.)

The worst performances to be heard in the game are possibly those which occur in what would otherwise have been a tear-jerking moment. This scenario, which would have been heart-wrenching, is actually made rather comical by the exaggerated country bumpkin accents of certain characters in this scenario.

CONVERSATIONS:

Most of the voice-overs and interactions between characters are experienced through the game’s system of conversation. This system is itself a tribute of sorts to conversation systems in other games, which had the player watching barely animated portraits of characters which are swapped in and out as characters take their turns to talk.

However, Dust: An Elysian Tail goes a bit further by adding lip animation and slightly animated body language to the portraits.

These are pleasing to look at initially, at least until one notices that there is not a lot of variety to the portraits, which are reused for so many conversations that they would eventually turn stale. The lip animations also hardly construe as lip-synching, eventually giving the impression that the characters are just yammering away. The generally hammy voice-acting further reinforces this impression.

Fortunately, Dean Dodrill has enough time in his hands to make some special artwork for certain conversations. An example is shown below; this is the player’s “reward” for following a certain side quest.

For players in a hurry, characters’ lines during conversations can be skipped, either line by line through on-screen buttons or by one entire tract through using the “Esc” menu.

However, if the conversations are broken up by animations, the player cannot skip through all of them in one go. This is because the animations themselves cannot be skipped. This can become an annoyance for particularly tough battles, such as those involving main bosses, which are often preceded by long expository dialogue and animations outside of the conversation system.

VISUAL DESIGNS – CHARACTERS:

As mentioned earlier and as is evident from the screenshots, the characters are mostly anthropomorphic animals. However, which real-world animals they are is not made so obvious due to their very human clothing, most of which is rarely simpler than a shirt and a pair of shorts. An observant player may notice the feudal Korean themes in the clothes too. Such detail is appreciable.

The eyes of the characters happen to take up sizable portions of their faces. This is hardly anything new of course; this facial design for anthropomorphic animals had been around for decades.

However, where other animators would alter such characters’ eyes, eyebrows and/or cheeks so that they are better at expressing their emotions, the characters in Dust: An Elysian Tail do not benefit from such attention to detail, at least during conversations. Their eyelids are used for such a purpose, but this technique is used so many times that it would become stale quickly.

It is only in the animated-film cutscenes where the eyes of characters are animated to be much more expressive.

Arrah’s visual designs are notable too, if only because it is a rather severe-looking sword which contrasts against its soft-spoken personality.

VISUAL DESIGNS – COMBAT ANIMATIONS:

Most of the animations for combat have been invested in Dust. Watching him swirl through enemies with Aerial Dust Storm is a joy, and even if his melee combos are not always useful, doing each of them just to look at the splendidly done animations is worthwhile.

Enemies are less animated, but each archetype of enemies does have enough animations so as to provide the player with tells. These tells are easier to see on bruisers, but for lesser mobs, they are often obscured due to the fact their sprites are often so close together when they outnumber Dust.

VISUAL DESIGNS – LEVELS:

As should be evident from the screenshots, the locales in the game are lavishly drawn and coloured. Each of them has immediately recognizable motifs, such as the vibrant forests for the first stage and dank caves of the subterranean stage.

Regardless of whatever visual designs which each level have though, all of them have one thing in common: inexplicably floating platforms.

All of them appear to be shaped in almost the same way; half-ovoid objects with their flat sides facing up. Although their gameplay functions are obvious, the game does not have any narrative excuse for their presence – not even excuses which use magic.

A similar remark can also be made about certain tunnels which Dust can only use after he has learned a certain move. These tunnels are impeccably chiselled; this makes them easy to spot, but one would wonder why they could be so smooth.

REMARK ABOUT OBLIGATORY UNDEAD-THEMED LEVELS:

There is a logical (and perhaps chronological) plot-hole about the obligatory undead-infested levels in the game. These levels depict a certain estate which have fallen into ruins. In addition to crumbling and mouldering, some buildings in this estate have deteriorated so much that they have fallen into a sink-hole.

This makes for great spectacles, but there is a narrative issue about this; this ruination could only come about in decades, realistically speaking. Yet, the plot-line for this set of levels suggests that the ruination had come about rather quickly, i.e. in a matter of years instead of decades.

Of course, one could argue that bad karma in the world of An Elysian Tail can result in terrible curses with very quick, tangible effects, but this would seem like a deus ex machina technique.

DIFFICULTY SETTINGS:

The game has very little official documentation on its difficulty settings. Other than stating that enemies become stronger and “smarter”, there are no mention of other differences when the player reads the descriptions of the difficulty levels when picking one for a playthrough.

One of these unmentioned differences is the aforementioned limitations on the healing capabilities of the monuments. In another example, a certain flying organic explosive in the game does a lot less damage in the higher difficulty settings. Yet another example is that at the higher difficulty settings, the lock-picking mini-game for treasure chests are more tedious.

There are likely other differences, though these require more observation and experimentation, e.g. the drop rates of loot, which are very much dependent on luck.

IN-GAME DOCUMENTATION:

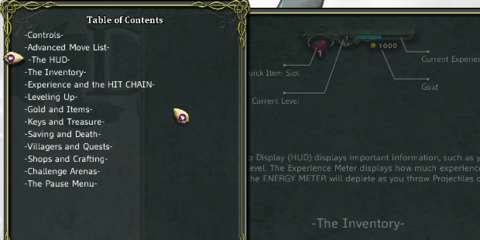

Other than the just-mentioned difficulty settings, the game describes almost everything else about its gameplay through its handy in-game documentation.

Things such as the controls and melee combos are meticulously documented and explained, so a player who has left the game for a while can get himself/herself brushed up on the basics quickly.

SOUND EFFECTS:

Fortunately, where the voice-overs falter, its other sound designs compensate.

The bulk of the game’s sound effects are the noises which Dust and enemies make when they are fighting. Most prominent of these are Dust’s sword swings and cuts, which sound very satisfying when the player is having him mow down hoards of enemies.

The noises which enemies and environmental hazards make are not particularly remarkable, but they do satisfy their function, which is to aurally indicate to the player that they are making attacks.

MUSIC:

The best sound designs in the game are its music. Indeed, it would be difficult for the player to remember anything else other than the music when he/she is prompted to recall the most impressive aspect of Dust: An Elysian Tail (other than its most obvious one, which is its furry characters).

In fact, HyperDuck Soundworks, which composed the music, has impressed Dodrill so much that they have been given a minor cameo.

Some of the soundtracks have also been contributed by Alexander Brandon through HyperDuck. Alexander Brandon is better known for having once worked with Epic MegaGames, before it turned into Epic Games.

The game starts itself off with the melancholic track for the main menu, “Falana” (apparently authored by Brandon). Eventually, it moves on to much more stirring tracks, such as “Abadis Forest”.

Interestingly, each track which is associated with the stages has two segments with different tempo. The segment with more exciting tempo is used for when fights occur. Such variety is refreshing, especially considering that most other games with lesser soundtracks recycle the same soundtrack for battles over and over.

The soundtracks for the game happen to be available for listening at Bandcamp currently, under HyperDuck Soundworks’ own profile. For better or worse, it would appear that the composer duo are planning to move their soundtracks over to sites which makes use of MP3s, as well as iTunes.

GLITCHES:

Unfortunately, a couple of years on, there are still technical issues with the game, at least for its Humble Bundle version.

The most common glitch is that items may get stuck in the terrain. This can be observed when enemies are slain too close to terrain obstacles; this can of course be avoided by slaying them away from these (though enemies are often easier to kill when juggled against such obstacles).

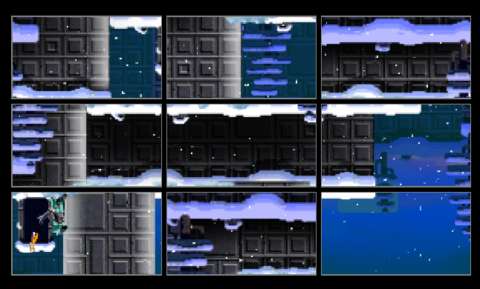

A much worse glitch can be experienced in one particular level in the Abadis Forest, specifically one which is used for a one-way loop-around.

From the entrance to this level, the player is supposed to drop onto lower platforms from higher ones, but if the player chooses to jump off the former instead, he/she might suffer a display glitch which turns the screen almost dark slate gray (with a tint of cyan) as shown below; the game also happens to freeze.

After the player has explored the area thoroughly and uncovered all secrets, the glitch is removed, curiously enough.

OTHER COMPLAINTS:

Dust: An Elysian Tail has its roots in the Xbox Live Arcade scene, and it shows – specifically in the limited number of save-game slots which the player can make. Despite the porting over to the computer platform, this has not changed.

Fortunately, this is not too much of an issue, because the game has a linear story and the player can backtrack to previously gone-through places.

The percentage indicator is intended to show how close the player is to completing the game’s story, but it also counts in secrets and other collectibles. This is perhaps a tribute to certain classic games with incredibly faulty progress indicators, but if it is, perhaps it should not have been replicated in this game because it is, after all, a bug.

CONCLUSION:

Dust: An Elysian Tail does have some design flaws, such as randomly triggering environment threats which reward good luck more than it does great skill. Some of its designs are also under-utilized, such as melee combos, which are not as useful as Aerial Dust Storm and Fidget’s magic. Its best strengths are also sometimes its worst annoyances, namely its ample references to other games.

The worst of its flaws lies in its generally hammy and exaggerated voice-overs, which mar the otherwise beautiful presentation of the game.

Still, Dust: An Elysian Tail’s other aspects are impressive enough or otherwise solidly designed that playing it is hardly a waste of time. If one has been hankering for a game with furries in it, Dust: An Elysian Tail might just sate such a yearning.