INTRO:

Dreamfall: The Longest Journey, the second game in the series, did not receive unanimous praise from those who have played the first game. Where the first game was a satisfying story that is complete enough to stand alone on itself, the second game has a cliffhanger ending and many unanswered questions, as well as some poorly designed gameplay. More importantly, it did not do well enough commercially for Funcom to provide financial backing for the third game.

its creator Ragnar Tørnquist (who is a significant Funcom employee) and his colleagues were not perturbed by the setback. Founding Red Thread Games, he and company went on to achieve a successful Kickstarter campaign and even secured funding from the Norwegian Film Institute (previously known as the Norwegian Film Fund). More importantly, Funcom willingly licensed out the production of the third game to Red Thread Games, thus clearing any legal obstacle.

The greenlighting of the game itself may have been a triumph, but how the game itself turned out is a different matter entirely. Having taken on an episodic nature, the game took more than one and a half years to be completed, and the end result has both proverbial polished surfaces and rough edges.

PREMISE:

The second game did not end well for the protagonists. Kian Alvane has been denounced as a traitor for doubting his orders, April Ryan is dead, and Zoë Castillo is in a coma, while her mind is trapped in the otherworldly realm of Storytime. The third game does provide a brief recap of what has happened, as well as a cutscene which makes it very clear that there will be nominally two protagonists instead of three.

Kian Alvane awaits execution. More importantly, he has been cast into a mire of self-doubt, putting him into inaction. Zoë is also not gaining much progress, even though she has discovered and learned to use her Dreamtime powers. (As for April, she is very much dead.)

However, due to events which are not within his control, Alvane is broken out of prison and has little choice but to join the resistance group which is opposing the Azadi occupation of Marcuria. He will have to learn to overcome his indoctrinated intolerance for magic and non-human races, as well as the less-than-kind attention of characters who do not like him for who he is and what he has done.

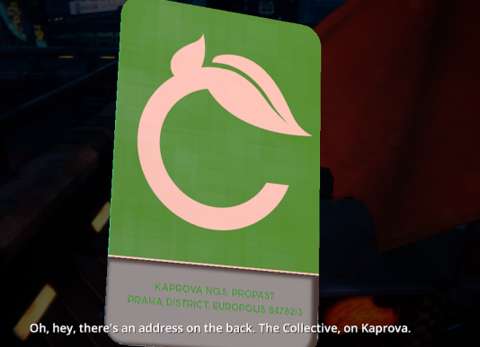

As for Zoë, she finally gains the courage to leave Dreamtime, but suffers memory loss in the process. She begins a new life in the city of Propast, away from Casablanca and her father, who has not been truthful about her lineage. She only faces new problems however: Propast is not a politically stable city, her relationship with Reza is on the rocks, she still has to come to terms with her amnesia, and WATIcorp is still keeping tabs on her.

There are agents at work who are conspiring to change the destiny of the twin worlds of Stark and Arcadia. Kian and Zoë will be pulled into the maelstrom, and depending on their decisions, quite a number of their friends may well die.

DECISION-MAKING WITH ALLEGED CONSEQUENCES:

One aspect of the game that is especially touted in its marketing is the supposed brevity of the player’s decisions. To elaborate, the game suggests that some of the player’s decisions are important, because they will have “consequences” down the line. These decisions are often highlighted with the game’s trademark symbol.

In practice, the impact of these decisions would not be that much different from those seen in Telltale Games titles. For one, the decisions mainly determine who would die and who would live – something that Telltale titles have done to death (pun not entirely intended). They will not change the overarching story in any way.

Consequently (tautology not intended), the most that the player would get from the game’s decision-making system is a limited degree of replayability. For example, there are very early decisions which determine which individuals from a pool of mutually exclusive characters that the player would meet throughout the game; the player will have to practically start a new playthrough just to see the “consequences” of the decisions which the player did not take the first time around.

The other decisions though, have consequences in the subsequent chapters, perhaps one “book” later but rarely much further. The player could ostensibly reload earlier game-saves and continue the playthrough from there, but this also reveals another problem with the game.

LIMITED GAME-SAVING:

The game makes use of a checkpoint-based auto-save system. This would not have been a problem if the checkpoints are frequent, but they are not. There is a checkpoint for the completion of a significant objective, but completing one might take considerable time and leg-work. This can be a problem if the player wants to reload a game-save to consider taking the other decision at a decision-making point which occurs in between checkpoints.

The player could make a manual game-save, but this only duplicates the latest checkpoint-save, though this duplicate would not be overwritten by auto-saves which occur later.

“BOOKS” & CHAPTERS:

Not unlike Telltale titles, Dreamfall Chapters was delivered piece by piece. Although the game’s story has finally been concluded, it retained its episodic packaging; each book is a number of chapters, and is nominally equal in length with the other books. The player will be making important decisions in each book, and the outcome of these can be seen in the later ones. However, as mentioned already, the impact of these decisions will not change the overarching story.

SOME MISSING TERTIARY CHARACTERS IN LATTER CHAPTERS:

There are some supposedly important decisions which involve certain characters who debuted in the earlier chapters. For example, there is the prison warden in Kian’s part, and Zoë’s therapist in hers. Ultimately, these characters have very little presence later in the story, and the consequences of the decisions which concern them do not have particularly visible effects on them.

For example, the prison warden is relegated to nothing more than statements by other characters in the later chapters about Kian’s exploits. As another example, Zoë’s therapist, Dr. Roman, does not appear again after the truth about his part in Zoë’s life has been revealed.

Although the game does well in retaining the presence of characters which do actually matter to the story from the start till the end, the diminishing presence of these tertiary characters suggests that the plot-lines concerning them have been deliberately simplified and then concluded. That they do not do anything that is particularly memorable may also contribute to this impression.

MOVEMENT & EASE OF EXPLORATION:

Like in the previous game, the player character has to move the currently controlled player character about in order to be able to do anything.

For this purpose, the player is given two movement speeds for the player character: a leisurely walk (regardless of the urgency of the current situation) or a brisk run (which may not match the urgency of the situation either). For most of the game, this is adequate, though there are certain environments where running is just too slow a method of getting around.

For example, there is the district in the city of Propast which Zoë lives in. When it is introduced, it can be a difficult place to move about in, mainly because so many of its buildings look like each other. Doodads such as billboards which are found in more than one place also do not help much in differentiating locales in this district. There are landmarks, such as the artificial sun in Sonnenschein Plaza, but they are obscured by the aforementioned non-descript buildings until the player character is in the immediate areas around these landmarks.

In contrast, the city of Marcuria has visual designs which are much more useful for the purpose of moving around. It is separated into districts, each with noticeably different surroundings. For example, the district in which the Rooster & Kitten bar is located has the most cobbled roads.

Fortunately, there is a system which goes some way towards the prevention of becoming lost in either city. This will be described later.

Any other locations which are not the city of Marcuria or Propast are a lot more linear in their designs. There may seem to be other paths, but these will lead down to dead ends. (These dead ends tend to have some items or objects which the player characters may have to interact with, however.)

In the later chapters, routes in the cities will be blocked off by soldiers. Although this change makes them more linear, they also become more tedious to navigate in, especially Propast.

MAP BOARDS:

In the city of Propast, there are map boards with on-board virtual intelligences, all of which are Crowboy the crow cowboy. The player can use them in order to obtain directions towards where the player character needs to go to. Conveniently, Zoë’s current location is marked on the map, which helps orientation.

The city of Marcuria also has map boards, but for better or worse, they do not have Crowboy, and they do not provide directions. However, directions are less needed here because of how much simpler the city’s design is than Propast’s.

Yet, as useful as map boards are, they are a poor substitute for a portable map. It can be hard to believe that Zoë, who does have an optical augmentation, does not have map software built into her augmentation. It is also hard to believe that Kian, who is trained to be a covert operative, does not have a map on his person.

Of course, one could argue that he is trained to memorize the layouts of cities, but if that is indeed the case, ready access to the view of a map could be explained away by him recalling an image of the map instead of him bringing out a physical map. The player should never be expected to possess the same skills as a video game character.

INVENTORY SYSTEM:

The inventory system can feel like both an afterthought and a frivolous design.

It is a row of slots which sidle up at the press of a button. More slots are created if the player has more items to collect than there are slots. The presentation of the slots are rudimentary at best.

The models of the items which go into the box are, in contrast, so much more detailed than the slots – perhaps too detailed. In fact, bringing up the row of slots can cause a noticeable slow-down.

These items are full 3D models. The player can examine each item, which causes the camera to zoom in on the item, showing all of its details (which are rarely seen anywhere else in the game). The player can rotate the item around. If not for the need to do this in order to solve some puzzles, such a feature might have given the impression that it was implemented for the sake of gratuitousness.

PUZZLE SOLVING:

As a series, The Longest Journey never did have particularly memorable puzzles. Whatever problems and obstacles which the player character would encounter are mainly there for the purpose of story-telling, and the player would usually be able to figure out the solution quickly. The third entry is not any different.

What is different about the third entry though is that it will require the player to move about a lot, especially in scenarios which occur in the cities. Chances are, what the player needs to solve a puzzle or overcome an obstacle in one place will be found in another place.

Adventure game veterans would not be perturbed by this, especially if they have a habit of trying to pick up everything that can be picked up without any plausible reason to do so. For players who would prefer that their puzzle-solving activity be guided by reason and logic instead of virtually kleptomaniacal tendencies, the going-to-and-fro can seem tedious.

As for the puzzles themselves, almost all of them are easy to solve, if the player has been paying attention to the statements of characters as well as observing the surroundings. Furthermore, the player characters have monologues which provide subtle reminders about what other characters have said to them. For example, at one point, Kian Alvane would recall something that another character has said about goats and a specific plant that they like to eat.

ARTWORK:

The best visual designs of the game can be seen in the artwork for characters and the environments. Many of them have plenty of polygons to their models, as well as textures with much normal mapping. The freckles and wrinkles on characters can be seen quite clearly. The lighting for environments makes convincing shadows and there are scant few instances where the dynamic lighting (and shading) of models seem jarring. Indeed, if the player has a powerful rig, the game can produce scenes which make for very pretty screenshots.

ANIMATIONS IN GENERAL:

Unfortunately, making pretty screenshots is pretty much what the game’s visual designs do best. They are terrible at making scenes with moving things and moving people.

The animations of characters do seem better than the animations seen in the previous game (and especially the first), but such comparisons would be done without regard for other games with similar emphasis on characters as tools of story-telling (especially Telltale titles). Running and walking animations are well-done, but animations for picking things up and handing over things are rather rudimentary.

FACIAL ANIMATIONS:

The most disappointing animations are facial animations. Most of the time, the player will not see anything more than eyeball motions, blinking and lip-synching from the characters. Any other facial expressions are exceedingly rare.

This would not have been an issue if the camera for cutscenes does not focus on their faces too much, but it does. This makes the limited facial animations stand out even more.

HEAD ANIMATION GLITCH:

There is a frequently occurring glitch which causes the player character to look over his/her right shoulder, even during conversations and when he/she is supposed to be looking at something.

The only way to fix this glitch is to reload a game-save. Yet, if the glitch occurs during a long stretch between checkpoints, this can be troublesome. Furthermore, there does not seem to be any noticeable trigger for the glitch, meaning that the glitch seems to occur randomly.

WRITING:

The writing has always been a plus-point for the series, enough to divert attention away from the shortfalls in its presentation. This is also almost the case for Dreamfall: Chapters, except that there are problems such as the aforementioned forgettable tertiary characters and the wasted opportunities to make them more interesting and consequential.

As for the travails of the protagonists, there can be considerable arguments over whose segments are more memorable. (As a reminder, Kian Alvane’s segments in the previous game are some of the worst, no thanks to the clunky combat that the player was subjected to.)

In Dreamfall Chapters, Alvane’s segments are more about his attempts to fit into idiomatic shoes which he has never worn before. There may even seem to be options for the player to have him fit in or fall out. However, regardless of the player’s decisions (which actually progress the story rather than those which lead to automatic game-overs), Alvane will always fit in, becoming an indispensable member of the resistance. The cruelest of things which the player could do is to have him lose some friends due to injury and death along the way.

There are themes of species-based prejudice in Alvane’s segments; these are perhaps the only relatable themes, vis-à-vis the real world. Other than these, everything else is quite fantastical, and if it is not fantastical, it is almost (but arguably not) like steam-punk or gaslight, specifically where it concerns Azadi hardware. These latter narrative elements are not well-explored though; they might be, in the sequel (if there is any).

In contrast, Zoë’s segments might have too many relatable themes, the most obvious of which is politics. Players who are fed up with politics might well be put off by her segments of the game, which are permeated with electioneering and intrigues.

Fortunately, these likely unpalatable narrative elements eventually give way to dystopian ones, which are more ominous and mysterious (albeit in typical ways as dystopian settings are wont to do).

SIMPLISTIC BUT EASY STEALTH SEGMENTS:

The previous game had tried to include some stealth segments, but like the combat segments, they were derided as incompetent at worst and barely bearable at best. Dreamfall Chapters has its own stealth segments, but instead of trying to improve upon what had been done, these resorted to boringly simplistic shadowing activities (i.e. following characters from a minimum distance).

The only good design in these is that if the player character is spotted, the game immediately resets to a nearby checkpoint, without any loading time whatsoever.

TIMED SEGMENTS:

There are some very short segments where the player character has to either enter an input just in time or enter a series of inputs within a time period. These are not exactly quick-time events, but they seem to be there just for the sake of gratuitousness. For example, there is a segment in which Kian has to catch an arrow just before it hits him. While it does remind the player that he is a bad-ass assassin, there is not much more significance to this scenario, such as learning about who is specifically targeting him instead of his companions who were with him at the time.

VOICE-OVERS:

For a game which revolves around a couple of protagonists, it is unfortunate that both of them are voiced by a rather lousy voice-actor and voice-actress. They will sound especially lousy when compared to the voice-overs for the supporting cast, like Crow and Likho.

Fortunately, the writing for the protagonists’ lines are good enough such that they are still worth listening to. As for the writing for the other characters’ lines, they do a good job of expressing their personalities. For example, Crow’s mild snarkiness shows through his lines, which are very much the only means of expressing his personality because most of his other presentation consists of typical bird-like motions.

SOUND EFFECTS:

Most of the sound effects in the game are ambient sounds. For example, there is whirring machinery within a man-engineered edifice. Other than these, there are the sounds which are emitted when the player successfully solves a puzzle or makes a breakthrough in a scenario.

MUSIC:

Of all the sounds to be heard in the game, the musical tracks are unarguably the most pleasant. There are tracks which evoke wonderment, which is appropriate since they often play in surreal locales. There are also ominous tracks, which are used for when the player character treks through sinister places. Most of the tracks are instrumental, though there are also electronic tracks such as the one which is used in the main menu screen to give it a melancholic appeal.

Unfortunately, the stand-alone tracks do not come with the regular license purchase for the game.

SUMMARY:

Dreamfall Chapters offers more of the entertaining writing and beautiful visual artistry which the previous games have offered. However, everything else about it seems lacking.