INTRO:

Divinity II: The Dragon Knight Saga was known for trying to do many things; one of these is the dragon-flight sequences, which have the player character flying around roasting things. However, it was not exactly well integrated with the rest of the game. For one, the dragon-form could only fight with enemies that are made for the dragon-flight sequences.

Larian has since developed a new game around this gameplay, while filling the rest of the gameplay with a rudimentary real-time strategy and 4X-lite elements.

PREMISE:

The game is set in times far before the events in Divine Divinity. Maxos, the favoured emissary of the Dragons, was a character introduced in Divinity II, but not seen in the flesh. He appears in this one, apparently as a concerned observer of the state of the world.

The reigning monarchy of Rivellon has been plunged into infighting after the death of its monarch. His empire has fallen into disarray, and his many bastard children vie for the throne. Their disagreements with each other have escalated into a civil war that threatens to damage the world irrevocably.

Maxos decides to intervene by endorsing one of the heirs, who happens to be the result of a dalliance between a dragon in human form and said monarch. With Maxos’s backing, this bastard prince would raise an army and empire to crush the others and return the world to peace.

In actuality, the game in this story is one of the most simplistic that Larian would have ever written. That the intro is delivered through goofy-looking silhouettes on papyrus would already be indicative of this.

SINGLE-PLAYER:

The bulk of the gameplay content is concentrated in the single-player portion of the game. This is perhaps to be expected, because multiplayer games had never been Larian’s forte. That said, the bulk of the story-telling is in this portion of the game too.

MULTIPLAYER:

The multiplayer portion of the game only has the battles. Due to the simplicity of the army-raising and base-building gameplay, which will be described later, matches are likely to be very short. The players would be fighting on equal terms, mainly due to the near-symmetry of the maps.

At least the multiplayer feature has the old but reliable methods of yore. The default method is to have games over LAN connections. The other method is direct IP connection, a method that is rather rarely implemented in games even during the time of this game.

THE DRAGON KNIGHT:

The half-blood princeling is almost immediately referred to as a “Dragon Knight” in the prologue, thus affirming the backstory in The Dragon Knight Saga of there being mortals that have been imbued with draconic might. Eventually, the protagonist gains the eponymous title of “Dragon Commander” as befitting his status as the commander-in-chief of his faction.

For whatever reason – likely a blessing from Maxos or from his mother – the Dragon Knight cannot exactly die in battle – he just comes back. This does come with a setback though – a large number of his subjects have to give themselves to his return (though it is unclear whether they are sacrificed or simply incapacitated). Of course, such designs are in the game to facilitate the gameplay of the real-time battles.

In the single-player campaign, he would be doing more than just fighting in battles. He has to be a statesman, a war manager and a political spouse (of sorts). All of these other gameplay elements feed back into the battles though, so the player should not expect complexity at the level of 4X strategy games.

THE SHIP:

The single-player playthrough begins with Maxos introducing the Raven warship to the protagonist. This is the player’s mobile base of operations, which so happens to be rather roomy. This is also where the player character interacts with the other characters to get closer to them or to plan the progress of the war campaign.

To simplify the navigation of the player character through the ship, there is a bar of buttons at the bottom of the screen. Each one is for a different section of the ship, and some are not available initially. Exclamation marks will also appear above the buttons too, indicating that there are things of interest in these sections.

Characters that the player character can talk to are given highlights when the player’s mouse cursor hovers over them.

CHARACTERS MOVING ABOUT THE SHIP:

The characters that the player character would meet generally stay on just one section of the ship. However, they will move from one section of the ship to another, occasionally. This is usually an indicator that something is up with them. The player would likely have a chance to make a decision about an event that involves them, or they may have something to say about the event.

THE BRIDGE:

The bridge of the ship is where the player makes the decisions that would advance the war campaign. It has a magical display of Rivellon, starting with one region of the world. The world is depicted with a presentation that is not unlike that in Risk.

Regions are represented as 2D plates with shaped borders and war assets are represented with figurines. As with Risk, the player (and the opponents) moves his/her assets around from one tract of land to another. Every figurine that has run out of moves greys out; any consequence from having moved the pieces will be resolved when the player ends the turn.

REACTIVE OPPONENTS:

The player’s opponents in the single-player campaign make their moves according to what the player has done; they are always aware of the movement of the player’s assets.

This can seem cheating at times, especially considering that the opponents always make their moves after the player’s own have been made. However, observant players may also notice that this makes them predictable.

For example, opponents always move their forces into lightly defended territories. This is usually not a good thing, but the player can always play cards later that turn the tide around. (There will be more on cards later.)

Players with some level of cunning would eventually learn how to exploit their responses. For example, the player can lure a massive enemy force into a lightly defended territory before playing cards that bring in units that can counter the massive enemy force.

ENDING TURNS:

When the player ends turns, the player’s moves are resolved first. If the player’s forces move into uncontested neutral territories, they are immediately claimed (whether the locals like it or not) and any assets that they have are immediately transferred to the player. If the player has ordered for the fielding of new units, they are produced at the end of the player’s turn and become available for the defence of the territory. This is something that is important to keep in mind.

If any opponents move forces into the player’s territories or any neutral territories that the player has moved forces into, or if the player has moved forces into enemy territories, these territories are considered as being contested. Any contested territories will have their battles resolved before the start of the next turn.

CANNOT THOROUGHLY REVIEW UPCOMING BATTLES:

The last phase of a turn is about the resolution of battles. This has been described earlier. The player is shown a zoomed-out perfect bird’s-eye view of the region map; territories that are contested have symbols of crossed swords on them. Hovering the cursor over each of these shows the percentages of success on either side. Little other information is available. This is the player’s only chance to review the upcoming battles and plan which battle would get which cards.

Afterwards, the battles have to be resolved one by one. The player does not get to choose which one to resolve first, or even which battle next. The player cannot return to the aforementioned bird’s-eye view too.

PLANNING BATTLES:

The planning of a battle is simple. The player selects any general to lead the player’s army, which can include the player character. However, each character can only be used once per turn. This is especially important in the case of the use of the Dragon Commander. As for the generals, each of them costs money to be deployed. Furthermore, each general can only be used once per turn and only if the player has enough money. The wages increase for each subsequent battle too.

Next, the player selects up to five cards to play for that battle. These cards are often the tide-turners in battles, especially those that have to be automatically resolved. However, there can only be so many of these cards, and using five for just one battle can be a lot (at least before the player gets many cards from careful development of territories).

The actual real-time battles will be described later. However, it should be said for now that an actual battle can only occur if the player decides that the Dragon Commander himself should join the fray. The player cannot have an actual battle without him (even though the gameplay system of battles could have allowed for this anyway).

NEAR-USELESS MAP-SHOWING FEATURE:

The player can see the layout of the map prior to the battle. Unfortunately, the map does not show the starting positions of the participants’ forces and does not show their starting assets, not even the player’s own. The locations of interest, namely the nodes for construction, are not shown either.

AUTO-RESOLVE:

Whenever the player picks any general other than the player character to lead a battle, the battle has to be resolved automatically. There is a bar that shows the probability of success, but that does not mean victory or defeat comes with an RNG roll. This is indeed just an estimate that is based on the assets that both sides have brought to the battle.

If the player has had plenty of experience with auto-resolving battles in other games that do this, he/she might notice that the mechanism is rather rudimentary. Only the units that are fielded matter, though any named general may provide relevant bonuses to them. Terrain does not seem to be an issue. The benefits or setbacks from the compositions of the armies are not clear.

The progression of an auto-resolved battle is shown in terms of ticks. Each tick shows the damage that is inflicted on the units. Which unit is damaging which unit is also not shown.

Obviously, the player cannot play cards that affect the Dragon Commander’s performance in auto-resolved battles because he simply is not there. However, the player can play the other cards, like the ones that improve the performance of units or introduce reinforcements. These do count as factors that determine the outcome of the battle. However, the increases in the probability of success can seem rather arbitrary, because there is no clear display of any information that leads to these changes.

TERRITORIES:

Controlling territories is what the player needs to do in each part of the single-player campaign. (The partitioning of the single-player campaign will be described later.) Ground-based territories are the only ones that the player can control.

The player always start with just one territory in any region, along with some units. This territory is the player’s capital. There may be some narrative disconnection between the presence of the capital and the mobile base of operations that is the Talon. Of course, gameplay-wise, the capital is there to be an Achilles heel that the player has to deal with.

The player’s goal is to expand the borders of his/her empire by capturing other territories. As mentioned earlier, “neutral” territories yield without a problem, unless they are contested. Enemy-owned territories have to be wrested through battle, of course; there will never be any negotiations with the protagonists’ half-siblings.

Any territories that are not defended by existing forces will be automatically conquered when opposing forces move into them. This includes even the capital, so the player should have garrisons in the capital or any other important territory, for that matter.

The immediate worth of a territory is determined by its population rating and its gold income. Its long-term worth is how easily defensible it is and conversely, how many avenues of attack that it opens up when it is taken over. For example, territories that are easily reachable is likely to be contested a lot.

CAREFUL CONTESTING OF TERRITORIES:

Observant players eventually learn about the limitations on waging battles, such as the (initial) scarcity of cards, the wages for generals that rise with the number of battles, and the fact that the player can only directly command a battle each turn.

Upon having learned this, such players would be careful about not over-extending one’s forces – a mistake that can be all too easy to make if the CPU opponents had not been doing much to fortify their territories. That said, although CPU opponents are not cunning enough to lure the player into making this mistake, they will exploit this mistake when it does happen.

CAPTURING ENEMY CAPITALS:

The key goal of the campaign is to capture the capitals of the opposing half-siblings. Taking them and holding onto them for one turn outright defeats them. Any of their territories and assets that they have prior to their defeat will transfer ownership over to whoever defeated them. This is a lucrative reward for concentrating effort on their capitals.

However, the opponent on the verge of defeat will not let the occupation complete without resistance. It will divert as many units as it can to the capital to rescue it. Other opponents, if they can, will also seize the chance to take over a weakened capital territory.

The capital cannot be removed, but it does not become an extra liability. In fact, the territory retains all of its benefits from having been a capital. Indeed, scoring a capital territory can be a tremendous long-term boost. The additional capital also becomes a buffer; the warlord that has multiple capitals must have all capitals wrested away before it can be defeated.

GOLD:

Gold is one of the two important resources in the Risk-like segments of the single-player campaign. This is the resource that is used in the fielding of units for ready-use in the player’s campaign and in the construction of infrastructure in the territories.

Gold is generated through the income from the territories, though it can come from some other sources whenever the occasions arise. Gold can go into the negatives, with any further income spent on clearing the debt first.

GOLD INCOME LIMITING RECRUITMENT:

Interestingly, there is a gameplay limitation on the fielding of units that is based on gold income. The total number of units that have been ordered for fielding cannot exceed the gold income of the territory that they are being raised in. This occurs even if the player has enough money to make those orders and more. This means that the player will have to decide on whether to build a gold mine or a war factory on a territory with high gold income.

This also means that capital territories can raise a large number of units rather quickly, due to their generally high income. Consequently, enemy capitals are very difficult to assault, because CPU opponents are very likely to spend all of the money that they have to raise standing armies.

RESEARCH:

The Raven has an archive full of texts in ancient languages; Maxos is plumbing through them to find skills to teach to the Dragon Commander. The Raven also has a workshop that eager Imps use to develop technology (or just get into mischief). Presumably, Maxos needs resources to sharpen his knowledge to craft lessons that the Dragon Commander can absorb quickly. The Imps need extra resources to focus their efforts, and to waste on silly experiments. (The true source of the Imps’ ideas would be revealed later in the single-player campaign.)

Every turn, the player accrues resources for research; they are simply called “research points” in-game. They can be spent on having the Dragon Commander learn draconic abilities, or unlock units for use and develop improvements to them. The costs are always shown to the player. Other than the costs, there is a limitation to the number of options that are initially available. This limitation is imposed by the player’s progress through the single-player campaign.

The player’s capital generates some research points every turn, but any more research points have to be obtained from other sources, namely the other territories. There is also the observatory, which is one of the buildings that can be built in a territory.

ENTRENCHMENT:

A controlled territory that has not been attacked for a while will accumulate “entrenchment”. This determines the amount of buildings that the defender would already have when a real-time battle starts. If the territory is attacked, it will lose entrenchment, regardless of who wins. The amount of reduction is not clear; presumably, an overwhelming victory for the attacker would outright reduce entrenchment to zero.

Entrenchment benefits the defender; that much is certain. However, the defender has no say on what has already been built. For example, there may be anti-air turrets already built, but the attackers are not using aircraft.

POPULATION DURING BATTLE:

Population is the main resource that is used during battle. The narrative reason for this is that although weapons and war machines are awash throughout Rivellon, they are not automated and require pilots and operators. They also likely require logistical support. Hence, manpower is needed, and so “population” represents the amount of manpower that the warlords can draw from.

Every territory has a popularity rating; capitals have the highest. This represents the amount of population that the territory currently has. When it is involved in a battle, all sides will draw from the same pool of population, which is shown in a parenthesis; the number that is not in the parenthesis represents the recruits that the player has accrued.

The rate at which this other number goes up represents the aggressive recruitment efforts of the player’s forces. The player can intensify them by building Recruitment Centres.

Theoretically, with enough Centres, the player could outstrip the opposition and get the lion’s share of the population. There is no way for the populations of territories to be restored during battle, so doing so would be advantageous.

LOW POPULATION DEFEAT:

When the population pool has gone down to zero during a battle, the battle goes into what is practically sudden death mode. The side with the most Recruitment Centres will begin to poach the recruits that the other sides have already obtained. The side that loses all of its recruits will lose outright. Therefore, battles of attrition can still occur, but due to the limited population pool, they will not last long.

POPULATION RESTORATION & LIMITS ON FORCES:

When a battle on a contested territory ends, the population of able citizens for that territory is reduced to the number of the population pool at the end of the battle. If the victor has more surviving units than it started with, the extra units have their population costs refunded to the pool. In other words, the victor does not retain any additional forces beyond what he/she has raised during the Risk-like portion of the gameplay. The population of a ravaged territory replenishes over every turn, eventually returning to its initial amount.

TERRITORY INFRASTRUCTURE:

Any territory, with the exception of the capital, can have infrastructure that contribute to their owners’ war efforts. The infrastructure includes staples in 4X-lites, such as resource-increasing structures (e.g. the gold mine) and unit-producing structures. The other structures generate cards over several turns; cards will be described later.

The player can sell the infrastructure on any territory at any time for half of the initial price. In particular, the player will want to sell any unit-producing buildings in territories that are far away from the front lines.

Besides, there is the matter of the increasing costs of buildings as the player builds more of them. Therefore, the player has to carefully decide which infrastructure to give to a territory, if any at all.

MOVING UNITS ON CAMPAIGN MAPS:

On the campaign map, units that have been raised can be moved from one territory to another, as mentioned earlier. Some units can move across two territories in one turn, while some can only move one. This is important to keep in mind; having an army group unwittingly split apart at an inopportune turn can be unpleasant.

Ground units can only ever move across ground-based territories. If they have more than one movement point, they can move across multiple ground territories in the same turn, as long as they are controlled by their owning player. Otherwise, ground units can only move into the outer-most territories of land that is controlled by enemies.

Sea units can move across water-based territories. Since water-based territories cannot be completely controlled by any warlord, sea units can move across any such territories without being impeded. The exception is when these territories contain enemies; the sea units must stop at these territories and cannot move beyond them, other than in the direction from where they came.

Interestingly, sea units can move into ground territories, but only those that are adjacent to water territories. They also have to end their turns at these territories. In the next turn, the sea units can move out onto any water territories that are adjacent to the ground territories – including even water territories that are on the other side of the ground ones.

Air units can move just about anywhere, except territories that are occupied by enemies. They can still go the long way around, but this also means that they are at greater risk of being over-extended than other units.

STACKS OF UNITS:

Before the start of any turn, the game automatically stacks units of the same type into one neat stack, if they happen to be in the same territory. This can be convenient or annoying, depending on whether the player intended to move them entirely as a stack or had intended to have separate stacks in the previous turn.

The game will prompt the player about moving the entire stack or moving just some units when the player moves a stack into a territory. The slider can be a bit finicky to use, especially if the stack does not have many units.

“NAVAL” BATTLES:

Naval battles occur whenever aerial or sea units are moved into sea-based territories that already have enemy units of the same kind.

These battles take place on water, with some isles in the centre of the map. The isles happen to have building nodes that can be used to build bases.

The catch here is that no side will have ground units by default. Even if any side happens to have transports with units loaded, the transports cannot unload their cargo onto the isles, because they just do not have any units in them when the battle started.

There is the impression that the developers have overlooked this part of the gameplay.

Anyway, any warlord can use cards that bring in ground units as reinforcements; this gives them the means of capturing the isles and use them to build bases. On the other hand, it is likely that the player is the only one that would do this, because the CPU-controlled opponents appear to have their decision-making scripts disabled for such maps. Their ships and aircraft would just stay where they are.

Indeed, if the player is patient enough, he/she could just wait for the dragon-form to become available. Unless the enemy has massed plenty of ships, it is unlikely that they can withstand the draconic onslaught.

It soon becomes clear that naval battles were never intended for real-time battles. That said, in auto-resolution, the side with the larger starting force generally wins.

There is almost nothing to be gained from such battles, other than knocking out enemy vessels, aerial or oceanic. Loaded transports are valuable targets of opportunity, however.

TRANSPORTS ON CAMPAIGN MAP:

In the campaign map, transports work differently from how they work during battle.

Transports can only carry up to five light units, whereas it could carry more during battle; presumably, the transport has to give up some space for supplies during the journey. If they are carrying heavy units, each heavy unit counts as two light units, in both the campaign map and during battles.

Loading units into transports does count as having spent the turns of the units that boarded. This is a caveat that the player should keep in mind. This also means that passengers are not able to do anything after they have disembarked. Speaking of disembarking, transports cannot contest territories until they have disgorged their units.

CARDS:

“Cards” represent the various non-monetary and non-research resources that the player has. Opposing warlords have these too, by the way.

Cards are how the player would turn the tide against enemies that seem to be well stacked in an upcoming battle. Incidentally, opponents would play their battle cards before the player does. Therefore, there are opportunities to play cards that are particularly effective against the opposition.

For example, more often than not, the enemy will mass its initial forces for an early attack on the player’s starting base; these forces tend to be sizable. If the player does not have enough forces to fend them off, defeat is inevitable. Therefore, the player might want to use reinforcement cards, which can bring in units that can absorb the initial onslaught of enemy units.

There are also cards that temporarily unlock upgrades for units or abilities for the Dragon Commander. These are useful if the player’s only choice is to go for quality over quantity. However, the cards become useless after the player has unlocked these abilities. There does not seem to be any way to remove these cards or benefit from their removal.

Outside of battle, there are cards that affect territories. For example, there are cards that improve the gold output of controlled territories. For another example, there are cards that blow up the infrastructure in enemy territories. It should be mentioned here that anyone’s territories are visible to the others. Players who have experience in board games like Risk would be quite familiar with these.

Cards are generated every few turns by infrastructures on territories. The countdowns to the granting of cards appears to be tracked for each infrastructure, instead of a lumped bequeathing.

As mentioned earlier, the costs of infrastructures rise with each subsequent infrastructure that is built. Therefore, the player will have to be efficient with whatever cards that he/she has.

PARTITIONING OF SINGLE-PLAYER CAMPAIGN:

For better or worse, the single-player campaign is partitioned into seemingly arbitrarily designated regions of Rivellon. The first region has the player fighting against only one of the usurpers. The second region has the player fighting against all of the usurpers. The third region has the player fighting against one opponent again, albeit a very well-resourced one. Presumably, these transitions are part of Larian’s plan for easing the player into the 4X-lite gameplay.

Unfortunately, Larian’s designers failed to inform the player about the caveats of the transitions. The player does not retain any units that have been made in the first region. The player does not even retain any economic benefits from the first region either.

The player is given one new territory and a handful of units. The total worth of these assets might be less than the value of the assets that the player has left behind in the previous region.

The things that the player retain are cards, gold, research points and any techs that have been unlocked. If the player has not hoarded enough of these, the first few turns of the next region can be daunting.

If the player has spent any gold on any assets in the first region prior to the transition, all that gold is spent and will not be reimbursed.

GENERALS:

Gameplay-wise, the generals are simply bonuses that the player picks to bolster armies in battles that would be auto-resolved.

They do happen to have roles in the story-telling, but the most that they would contribute to the narrative is their individual personalities and quirks – some of which can be rather petty, considering the war campaign that is going on. Perhaps some players could obtain some entertainment from their quibbles, but other players would consider them to be rather annoying.

Occasionally, things happen and they happen to be involved. These and the player’s decisions concerning them feed into the system of “politics” that would be described later.

After having followed their storylines, the generals eventually gain additional skills that contribute to the battles that they participate in. These additional skills help maintain their competitiveness as the playthrough wears on.

RACE RELATIONS:

Humans are the most pervasive species throughout Rivellon. They are common enough in fantastical settings that their presence in this game is not remarkable. In fact, they are not really represented in the gameplay, and in the narrative, “they just are” is the most significance that they have.

The dwarves and elves have been mentioned in the first two Divinity titles as being rare in the timeline of those games. Since this is a prequel, there are far more of them around. The dwarves and elves follow most of the typical fantastical stereotypes: the dwarves are greedy but hardworking, and the elves are soft-hearted sops.

The lizard race is also in this game; the lizards were virtually unheard of in the first two Divinity titles. Amusingly, in this game, they happen to be the most civilized race, or so they like to think.

Even more amusingly, the undead are a sapient civilization in Dragon Commander; they are just not the horrors and monsters that they would be perceived as by the time of Divinity II (or Original Sin, for that matter). Indeed, the player would be seeing silly things, like a barmaid with a wig and fruits for their bosoms. The most amusing trait about them is that they are ruled by a theocracy that venerates the seven gods (which have been introduced in the first Divinity game).

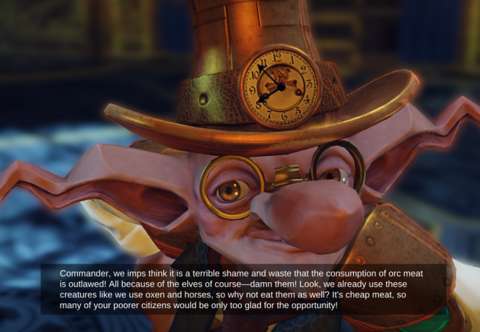

Then, there are the imps, who are incorrigible tinkerers who prefer to go out with a bang. They are also amusingly ruthless, e.g. having no issue with illegal labour.

Such entertainingly ridiculous diversity of races is what the player encounters when dealing with what passes for “politics” in this game.

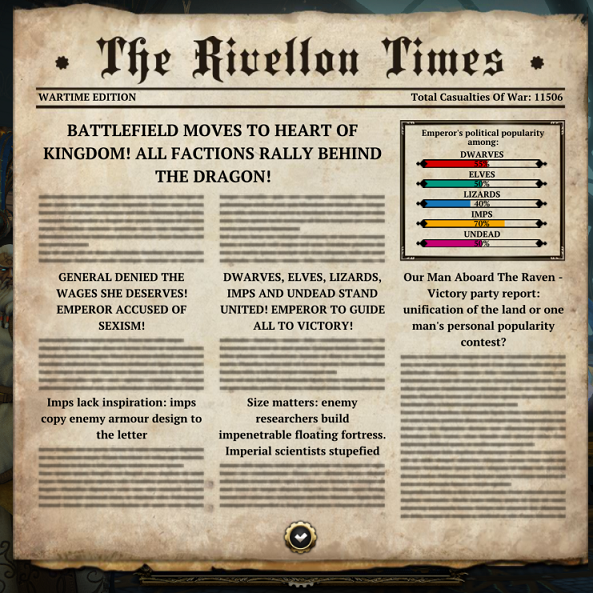

Before elaborating on the political things, it should be mentioned that whatever decisions that the player makes (or don’t), the player’s faction will endear itself to some races while upsetting the others. The player’s popularity with the other races is displayed with meters and percentages; generally, higher is better.

Thus, if the player intends to keep the races happy, the player has to juggle decisions to maintain the popularity ratings.

PRODUCTIVITY OF TERRITORIES:

Each territory in the campaign maps is inhabited by a majority race. In turn, the general productivity of the territory is determined by the player’s relations with that race. Happier races can eke out more gold and research from that territory and replenish its population more quickly.

There does not appear to be any other setback from having poor relations, in addition to lousy productivity. Rebellion is not a concern, because according to the narrative, the Dragon Commander’s faction is at worst still the least bad choice.

POLITICAL ISSUES:

As the campaigns wears on, the player is notified of political developments involving the myriad of races. Incidentally, shortly after the player character has established himself as a viable contender to the throne, the representatives of the other races flock to his banner. This is mainly because his siblings are outright psychos that could not be reasoned with, much less manipulated.

That said, these representatives will put forth issues that they are concerned with. Many of these concerns involve the war, such as issues with refugees, humanitarian aid and newly liberated territories.

They expect the player character to address these issues with policy edicts. Generally, the ones who put forth the issues already have drafts of the edicts, and expect the player character to pass or reject them. Predictably, only some of them are in support of the drafts, whereas the rest of them would be opposed to it. Siding with one side upsets the other; the effects on race relations are then applied in the next turn.

Even if the player ignores these issues, the representatives will vote on the issues anyway; this happens to be the privilege that they get for declaring their allegiance to the Dragon Commander. The player has no say over this privilege, of course. The effects of the vote will be applied anyway too. Therefore, the player might want to pay attention to these issues, if only to have more control over the proceedings.

EFFECTS OF POLICIES:

Other than race relations, the player has no knowledge about what else the policy edicts would do to the war efforts, regardless of whether they are passed or rejected. The effects are only shown at the start of the next turn.

Some effects are unique to certain policies, such as the one shown in a screenshot in this article. Most others have only two factors in the effects: “motivation” and “luck”. Neither is well explained in the documentation of the game.

That said, “motivation” is how much of the entrenchment bonus that the player would get from defending a territory. “Luck” is a minor but hidden factor that affects the outcome of auto-resolved battles.

PRINCESSES:

Apparently, having to issue edicts is not enough. Having been proclaimed Emperor by the representatives of the peoples of Rivellon, the peoples expect the Emporer to have a spouse. Of course, the player has no say in this.

For the purpose of having the Emperor wedded, the various races would send forth their most ravishing princesses (at least according to their standards, or rather Larian’s designers). Amusingly, the imps’ princess would die in an accident. In truth, Larian ran out of resources and time to implement her. (This is not the only thing that is not implemented, however.)

After having selected one to marry without angering the others (thanks to Maxos’s expert social discretion – and perhaps some use of magic), the player begins a storyline that concerns the princess’s personal issue. This is different from one princess to the next, and may even differ in number of potential outcomes. Amusingly, their appearances change according to the outcomes; some can be rather drastic, such as those for Undead Princess Ophelia.

Other than effects to race relations, motivation and perhaps luck, the princesses’ storylines do not contribute much to the war – unless of course, the player makes use of the last gameplay element to be introduced in the single-player campaign.

CORVUS THE DEMON:

The Divinity series has not been entirely clear about what demons are. They have been described as extra-dimensional creatures but there have not been any consistency in their appearances or their capabilities. The most powerful ones have powers and knowledge far beyond the ken of almost everyone in Rivellon.

That said, after a certain plot element has been revealed, one of these god-like demons is introduced. Corvus is a demon that somehow knows about arcane technologies, and freely gives such knowledge away so as to encourage the waging of war. Corvus also has the ability to stalk the dreams of anyone who sleeps.

Yet, somehow, Maxos has trapped Corvus in the Raven warship and instead of keeping quiet about it, decides to confide in the player character about their secretly treacherous captive.

Afterwards, the player gains the choice of sacrificing things to Corvus. The player character can sacrifice entire populations to (somehow) raise the opinions of races about him, or to gain gold and other resources. The player character’s spouse can also be sacrificed for power.

All these are as heinous as they sound, and there would indeed be setbacks later for having sated Corvus’s appetites.

In practice though, only terrible players who refuse to reload game-saves would be desperate enough to make such bargains. Experienced veterans of strategy games would not find the game too difficult such that they have to resort to this. Of course, some players might want to do this anyway, if only to get a more challenging third act for the single-player campaign.

If the player sacrifices a princess, the player can then pick another, who is none the wiser about what happened to her predecessor. The player can of course continue with the sacrifices until none are left.

BATTLES – OVERVIEW:

Ultimately, the real-time battles are the main focus of the game. Just about everything else in the game feeds to the battles.

Some of the basics of the battles have been mentioned already, such as the use of only one type of resource, and how running out of this resource triggers the end of the battle. Each side’s starting forces, be they units or buildings, have also be described.

Other than what a participant has brought into the battle, everything else would have to be raised during the battle itself in the effort to obtain victory. This is easier said than done, of course, but the rather simple mechanisms of the real-time battles should make doing so only slightly harder.

NO FOG OF WAR:

There is no fog of war, meaning that anyone can look at what the others are doing as the battle unfolds. This does not affect gameplay balance as adversely as one would think.

In multiplayer, the player can glance at what the others are doing. Yet, considering how fast paced the gameplay is, mere glances can be costly in terms of time spent, especially if the player does it too much. In single-player, the lack of fog of war lets the player match the CPU-controlled opponent’s ability to know exactly what the human player is doing.

CONSTRUCTION NODES:

Each map has building foundations; for ease of reference, they will be referred to as “nodes”. These nodes are in turn categorized into several types, which determine what can be built on them. The general appearance of the nodes indicates what type of structures can be made on them. For example, the octagonal nodes allow the building of recruitment centres, but nothing else.

Since the nodes are pre-existing locations and structures can only be built on them, controlling the nodes are key to controlling the map. Incidentally, most of them have been placed at strategic locations on the map. Some nodes, especially the ones at the starting locations of any side, are surrounded by indestructible walls or terrain that is impassable to ground units.

Capturing nodes is relatively simple; the player only needs to have units in their vicinity. By default, the nodes have to be cleared of existing structures too, if they were owned by the enemy. Initially neutral nodes will yield whatever structures that are on them, however.

Troopers that have been upgraded are able to capture enemy controlled nodes without having to destroy existing buildings. However, they have to do so at close ranges. Furthermore, this is not always efficient because it takes a long time for a single Trooper to capture anything and having many Troopers just to capture buildings might not be a good idea.

DEFENSIVE STRUCTURES:

Defensive nodes are the smallest nodes. These often appear near the other bigger nodes, though they may also appear at chokepoints in the map.

These allow the construction of defensive assets, namely the anti-ground and anti-air towers. They are powerful enough to wreck light units if they are not massed, but heavier units would eliminate these quickly. Still, they are likely to be the player’s best chance against any early-match rushes from the enemy’s starting forces.

In the single-player campaign, the anti-air towers would be of particular concern to the player. These fire very fast missiles that can hit the dragon, even if it is using its jetpack.

CONSTRUCTION AND DECONSTRUCTION:

Through arcane sciences, buildings fade into place from out of nowhere. Building them only requires a handful of recruits (presumably for the ritual), but each building takes quite a long while to be finished. There are no readily available means of accelerating their construction. (There are no constructor units, by the way.)

Buildings can be sold for half their value; they immediately disappear afterwards (thankfully). Buildings that are being constructed uses the same selling mechanism to be sold, but they are refunded in full – so far, so familiar.

Buildings that are being constructed gain hitpoints from zero, and are only finished when they reach 100% hitpoints. This means that buildings that are under fire would never be completed if their hitpoint gain rate cannot surpass the damage being inflicted. If they are destroyed, their costs will not be refunded.

On the other hand, distracting enemies – especially if they are CPU-controlled – with buildings under construction is a handy stalling tactic. (However, the hard-counter to this happens to be hostile take-overs by enemy Troopers.)

QUEUING UNIT PRODUCTION:

Like other competently designed RTS games, Dragon Commander allows the player to queue units for production; each order will have to be paid up-front. After they have been cranked out, they move to rallying locations that the player has set.

Unfortunately, the game is missing a convenience that has been around in games like Supreme Commander. This is the convenience of setting the production queues on repeated loops. Perhaps the requirement of having to pay for each order prevented the implementation of this, but this should not have been too difficult to code around.

UNITS CANNOT MOVE THROUGH EACH OTHER:

Everything that the player sees during battle is a 3D model with collision hitboxes. That said, they cannot move past each other. This will be important in dealing with chokepoints and massing for an attack.

The CPU-controlled opponent appears to be partially aware of this. It will wait for units to mass at a location away from their intended destination. However, it does not wait until all units are there; it sends them out after a few seconds of massing. Incidentally, exploiting this is how the player can destroy the enemy’s starting forces piece-meal.

Units cannot move through each other but they can shoot past each other, so having armies of mixed units is not an issue.

UNITS CANNOT MOVE AT THE SAME SPEED:

Mixed armies are indeed needed for victory, mainly because the enemy rarely if not never raise thematic armies (not even the CPU-controlled opponent). Unfortunately, there is the problem of units within the same group moving at their own individual speeds instead of the slowest unit. Furthermore, when units of the same speed move together, they move in column convoys and only assume more defensible formations at the destination.

Experienced RTS players would know that this puts unit groups at risk of being destroyed piece-meal, starting with the fastest ones. This can be addressed with frequent massing, but this requires a lot of hands-on minding.

CANNOT SHOOT PAST SOLID TERRAIN OBSTACLES:

Any solid terrain obstacle that is in the line of fire or projectile trajectory will prevent units from attacking. The impeded units simply will not fire and will attempt to move over to another location where they can attack the target.

In the case of the dragon-form, attempting to attack anyway will result in shots landing on the solid obstacle. Furthermore, solid terrain obstacles also impede area of effect spells.

LIGHT GROUND UNITS:

Light units are the first tier of units that everyone has. Two of them are available right from the start: the Trooper and the Grenadier. There are more, and each of them happens to be the basic unit that fulfils a role in a balanced army. For example, the Shaman is the main healer of the army and the Warlock is the first glass cannon.

Since they are among the units that are available from the start, they have associated upgrades that make them more competitive in the late-game. For example, the Warlock is a terrible unit without its abilities, but after it has been upgraded, it is capable of dumping a lot of firepower in a short time if the player can micromanage the usage of their abilities.

Most light units are fast on the move, but the Shaman has been deliberately made slow. Therefore, armies that depend on Shamans to keep them alive will be quite slow. (Again, there is that matter of units not moving at the same speed.)

The Warlock and Shaman can hover over water without any problems, thus allowing them to provide support to naval units.

MEDIUM GROUND UNITS:

Medium units are substantially more specialized and bigger than light units. They can inflict a lot of damage to anything that they have been specifically made to counter. For example, Hunters are specifically meant to wreck light units. However, they take up more space on the battlefield (and in transports), so massing them is not as easy as massing light units. They are also generally slower than light units.

MEDIUM SEA UNITS:

There are no small sea units, likely because the Shaman and Warlock have already filled that tactical niche. Thus, the first sea unit is a large one: the Transport. Interestingly, compared to typical transport units in other RTS games, or any strategy game for that matter, Transports are very tough, and they are outright armed with missile launchers.

Ironclads are meant for naval superiority. They can attack ground units too, but they are meant to knock out other sea units, especially the Juggernauts.

HEAVY GROUND & SEA UNITS:

The Devastator is the only type of heavy ground unit. There could have been more, but they were not fully developed and implemented. The Devastator is a very large ground unit, making efficient massing of them near impossible. However, a squadron of them removes buildings very quickly, and they are tough enough to sponge concentrated fire long enough to knock out critical buildings anyway. Of course, they are also very efficient against massed enemy forces.

Like the Devastator, the Juggernaut is the only heavy sea unit. Like the ground unit, it is meant to be an artillery unit; in its case, the Juggernaut is far more effective at bombarding targets thanks to its rather long range. However, it is of course limited to just moving on water. Interestingly, the Juggernaut can be upgraded to give it the ability to build and launch Imp Fighters, which compensate for its lack of anti-air capabilities.

AERIAL UNITS:

Not counting the Dragon Knight, there are only three types of aerial units: the Zeppelin, Imp Fighter and Bomber Balloon.

The Zeppelin is intended to be a support unit; it extends the attack range of any units in its area of influence. Obviously, having greater range when the enemy does not means being able to shoot first, though the range advantage is just enough for just one unanswered exchange. Incidentally, CPU-controlled opponents rarely use Zeppelins.

The Imp Fighter is an aerial superiority aircraft. Squadrons of them can knock out almost anything from the air, except another enemy squadron. They also happen to be quite effective against the Dragon Knight, thanks to their fast guided rockets. Indeed, the CPU player would be fielding Fighters just to deal with the player character, and in multiplayer, human players are likely to have a squadron around just to deal with enemy dragons.

The Bomber Balloon does exactly what its name suggests: it drops bombs on enemies. Bomber balloons have to fly almost directly over their enemies, however, meaning that they are likely to stray within the range of enemy anti-aircraft assets. On the other hand, they are among the toughest units in the game, despite being what are practically hot-air balloons.

UNIT UNLOCKS:

Not all units and their capabilities are available for use from the get-go. How they are made available depends on whether the player is playing single-player or multiplayer.

In single-player, the player unlocks units and additional capabilities for them through the engineering bay of the Raven, as mentioned earlier. The player pays research points for them, as mentioned earlier. Whatever that has been unlocked becomes permanently available for the player’s forces. However, there does not seem to be any way to unlock units or upgrades for them during battles (despite a tip in the loading screens that imply that this is possible).

In the case of enemies in single-player, they do not follow the same rules. They appear to start with a number of techs according to the level of entrenchment of their territories, if they are the defenders. They are notably not so able to quickly field high-tier units when on the attack. However, they will spend recruits to unlock techs as the battle progresses, possibly surpassing the player if the player does not end the battle as soon as possible.

In multiplayer, players have the means to access the research tree. They spend recruits to unlock the abilities for units, and have to do so from scratch.

Maxos will inform the player that the enemy has unlocked techs, but will not mention exactly who has done so (unless of course, there are only two sides in the battle).

UNIT SPECIAL ABILITIES:

Some unlocks for units grant them buffs, such as boosts to the movement speed of Troopers and Armours. Some others unlock additional functionalities. For example, Hunters and Grenadiers can be upgraded to fire rockets, which make them less vulnerable to aerial units and – especially – Dragon Knights. These do not require the player’s attention, so they are worth going for if the player is not particularly skilled at micromanagement.

The other abilities require the player’s attention, because they will not use them themselves. These can be abilities that require manual targeting on the player’s part. Others are mode toggles, such as the Devastators’ siege mode (which is, of course, something that originated with the Siege Tank in Starcraft).

These all seem to be decently solid designs. Unfortunately, there is a problem: the user interface is not particularly good at helping the player use the special abilities that are available to a mixed force. Which type of unit is being currently selected in such a force is not highlighted in the user interface with sufficient contrast (if there is any highlight at all).

ARMY LIMIT:

In addition to their costs, units also have costs in terms of “support” points. The support points of all units are totalled up, which in turn represent the size and power of the player’s forces. This total cannot surpass a hard cap. This is, of course, a balancing design for the size of a player’s forces.

CASUALTIES IN CAMPAIGN AFTER REAL-TIME BATTLE:

In the single-player campaign, the auto-resolved battles will inflict casualties on all sides, with no means of replenishing them.

The determination of casualties in the real-time battles are not so clear-cut, because the player has the means to replace units. By the way, since there is no system of experience levels for units, there are no differences between those units that had been around for a while and those that are fresh from the production buildings.

The game appears to remember the composition of starting units in a battle. If the battle ends with the victorious player having less units of any type than there were in the initial composition, casualties will be inflicted in the campaign screen. That said, if the player raised any more units than there are in the composition, the surplus units are not retained. (Presumably, as mentioned earlier, these may not be considered as part of the player’s standing armies, but rather press-ganged or conscripted people.)

Of course, just like the auto-resolved battles, the loser always suffer 100% casualties in the real-time battles.

THE DRAGON IN BATTLE – FOREWORD:

The main appeal of the game is having “dragons with jetpacks”. This phrase is exactly the summary of whatever attraction that the player may have towards Dragon Commander.

In the real-time battles, the dragon-form can ravage most units that had not been massed. Even if they had been massed, most of its attacks, including even the default attacks, have areas of effect, allowing the dragon-form to savage multiple targets in a short time. Thus, the player would be using the dragon-form often to destroy forward elements that the enemy has been sending – especially the units that opponents have sent out to capture building nodes.

The dragon can be summoned in the battlefield at any location that is close to construction nodes or a substantial mass of units under the players’ control. The latter option allows the player to have the dragon support his/her units when battle commences, or just draw fire from enemies and return fire (literally) in response.

RECRUITS COSTS:

Summoning the dragon-form into battle requires recruits; the first fee is 20 recruits. If the dragon-form is defeated, the fee becomes higher and has to be paid again to return the dragon to battle. Presumably, they are expended to prepare the dragon-form for battle, or perhaps they have been used for some nefarious purpose.

Speculation aside, this is the gameplay-balancing design that is intended to discourage the player from being careless with the dragon-form.

COOLDOWN:

The dragon-form cannot be summoned and dismissed willy-nilly. At the start of the battle, the player has to wait more than one and a half minutes for the dragon-form to become available. This is intended to prevent the player from using the dragon-form to knock out the opponent’s starting structures or units. When the player dismisses the dragon-form, the player needs to wait 10 seconds before being able to summon it again.

DISMISSAL:

The dragon-form can be dismissed at any time, as long as it is close to the player’s own forces or bases. It cannot be dismissed while it is close to enemy bases or over enemy forces, meaning that the player must do actual hit-and-run attacks instead of simply dumping damage before having it discorporate.

The dismissal animation takes half a second, during which the dragon-form can be injured. Also, when it returns, the dragon-form retains the hitpoints that it had prior to being dismissed earlier. The hitpoints will never be shown to the player outside of moments when the dragon-form is not around, so the player has to keep them in mind.

DEFAULT ATTACKS & OVERHEATING:

The dragon-form’s default attacks are not fire-breaths, but rather fire-spits. The dragon-form can dump a lot of these, each of which has area of effect too. Packed enemy units, especially if they are light ones, would be devastated rather quickly.

However, the player cannot fire off the default attacks forever. The dragon-form would eventually overheat; the progress to this is shown by a circle that becomes fuller as overheating approaches. Overheating prevents the use of the default attacks until the dragon-form has cooled down completely. Overheating does not prevent the use of dragon abilities, but it does crimp the dragon-form’s damage output.

The dragon-form cools down half as fast as it builds up heat from continuing to use the default attacks. Thus, the player will want to ease up on the default attacks to avoid overheating. There does not seem to be any way to accelerate cooling, however. (The dragon-form cannot dive into water, by the way.)

JETPACK:

The jetpack is referred to quite a few times in the playthrough of the game. This is understandable, because it is not often that a Dragon Knight would strap something on his/her dragon-form’s back to further bolster their already great capability at flight.

The jetpack allows the dragon-form to cover long distances in a short time. It only takes a few seconds to fly from one edge of the map to the opposite edge through the use of the jetpack’s forward-boost. That said, the forward-boost does not appear to consume any fuel, but it only allows forward movement. The dragon-form can make a tight turn when moving at high speeds, however.

DODGING:

The dragon-form can dodge sideways, much like the dragon-form in The Dragon Knight Saga. The addition of a jetpack has allowed for more directions of movement, however. Indeed, holding down a button and then entering any directional input has the dragon-form dodging in that direction. Dodging does not grant invincibility, but the dodging does shake off tracking projectiles and makes enemies unable to target the dragon-form with anything.

Dodging drains the dodge meter, which is opposite of the health meter. It will not take long for continuous dodging to drain the meter completely, so the player will want to be sparing with the dodges. Furthermore, the dragon-form does not cool down when it is dodging.

HEALING:

The dragon-form is tough and can keep going until it loses all hitpoints, but concentrated anti-air fire can severely injure it and force a withdrawal. As mentioned earlier, the dragon-form will retain any hitpoints after dismissal and re-summoning. Therefore, the player must find means of healing the dragon-form.

The dragon-form regains hit-points even while under fire, though this happens at a slow rate. Being outside of combat and not taking damage for a while will begin a very fast replenishment process.

The player can also approach Shamans for healing, though only one Shaman can heal the dragon-form at a time. The dragon-form also has too many hitpoints for a Shaman to heal quickly and reliably.

Alternatively, the player can use certain dragon abilities to heal. One of them restores more than half of the dragon-form’s hitpoints after a short animation. The other one is much better, because it heals the dragon-form even as it is attacking enemies.

DRAGON ABILITIES:

Presumably after a crash course by Maxos, the player character gains an ability that his dragon-form can use. However, the dragon-form cannot use all abilities that have been unlocked. Rather, the dragon-form can only use up to ten of these, including any passive abilities.

This limitation is of more relevance to the multiplayer matches, because it provides balance. For one, having different capabilities for a player’s dragon-form compared to the other players’ can be advantageous in certain situations while being disadvantageous in others.

In the single-player campaign, the player might realize that only a handful of abilities are useful, because the opponents do not even field Dragon Knights of their own throughout the single-player campaign. (Apparently, this would have been too much for Larian’s programmers.) For example, the most useful abilities are the area-of-effect ones, mainly because the player would have to deal with massive groups of enemy units.

There is no good reason to have the other abilities, so the feature to unlock dragon abilities with research points might seem wasted.

DIRECTING UNITS IN DRAGON-FORM:

There are controls for directing units around while in dragon-form. The player can use already-assigned hotkeys for these, and then use shortcut keys to direct them around. The “Alt” keys are also used to work around the assignment of the number keys to dragon abilities.

There are also controls that select nearby units or buildings, or those that are under the player’s cursor. Players who have played real-time strategy games that have been designed for controllers would be familiar with these.

It is possible for the player to practice enough that he/she could efficiently raise armies, develop bases and build expansions even while in dragon form. Other players would have to dismiss the dragon-form and use the more convenient keyboard and mouse configuration to do all the RTS-related control inputs.

NO ENEMY CHAMPIONS IN SINGLE-PLAYER CAMPAIGN:

There will never be any opposing Dragon Knights in the single-player campaign. There will not be any special enemy units either. Indeed, there will not be any single individual enemy that is capable of matching the player character’s dragon-form.

It would not take long for an observant and competent player to notice that there will not be any worthwhile challenger. The only significant challenge that the single-player campaign would pose is the Risk-like portion of the gameplay, especially at the beginning of each Act.

Perhaps the worst lost opportunity is the relative lack of representation of the half-siblings. They are only ever referenced in the cheap cutscenes; not one of them is mentioned by name in the other parts of the single-player campaign. They also never appear in battle.

VISUAL DESIGNS:

The game makes use of an earlier version of the engine that would eventually be used to build Divinity: Original Sin. It is noticeably capable of generating plenty of curvaceous edges, be they the scales and contour of the dragon forms, or the curves on lady characters that are not undead.

There are some vestiges of visual designs from Divinity II, some of which can be seen in the animations for General Henry, who look a lot like he had been based on the male character models in that older game. The ladies are where the advancements in Larian’s model designs are the most obvious; their animation rigging is substantially more convincing than those in Divinity II.

Perhaps the most amusing visual designs for characters are those for the princesses. Many of them are amusingly curvaceous and show plenty of skin, thus harking back to the days of Dragon’s Lair. Some of them are even notably different from their species. For example, the Lizard princess looks very different from the Lizard representative Prospera, who is of the same gender. Indeed, she lacks a reptilian snout.

The units are mechanical war machines. Conveniently, they do not have a lot of moving parts. Most of their animations have their entire models or specific polygons in their models shuddering. They have textures, with decals depicting battle damage appearing on them as they take damage. Smoke and fire spews out of them as they come closer to destruction.

Of course, such visual designs would be nothing new to players that have played RTS games with 3D engines. Indeed, most unit designs seem forgettable. If there is anything notable about them, it is that there is no foot-slogging infantry whatsoever. Even the “Trooper” is actually a person sitting in the cockpit of a bipedal walker.

The most entertaining visual designs are those for the eponymous Dragon Commander, of course. Having a jetpack on a dragon is understandably one of the most ludicrous things in fiction, and Larian has certainly capitalized on it. Few of the dragon-form’s animations appear to have been recycled from the Dragon Knight Saga. Indeed, most of its animations seem to have been made for this game.

SOUND DESIGNS:

There are plenty of things to hear from the game, though not all of them would be pleasant to listen to in the ears of every player.

The RTS segments have plenty of explosions and noises that would be associated with sci-fi weapons, or to be more precise, sci-fi and magic hybrids of them. The player should expect plenty of synthesized pew-pews, zings and warbling. The sound effects that the player will actually want to listen to are those that signify the completion of building construction.

The best sound effects in battle are those that are associated with the dragon-form. For example, there are the entertaining blasts that accompany the pummelling of enemies when the dragon-form rains fireballs on them. There is the deep beating of the dragon-form’s wings as it flies about at normal speed. The best sounds are the roars of the dragon-form’s jetpack as it zooms through the map.

The voice-overs are the most numerous sounds that the player would hear, aside from the sound effects. Indeed, the voice-acting in this game sounds far, far more competent than the ones in The Dragon Knight Saga. (This game does have the advantage of having far fewer voiced characters, of course.)

On the other hand, most of the characters in this game can be quite insufferable because they prattle on and on about their species and culture and denigrate those of others. This can be especially annoying to players who are more interested in the strategy portion of the gameplay than they are the role-playing portion of the game.

As for the unit responses, most of them would be quite familiar to veterans of RTS games with goofy settings, especially the Red Alert and Generals sub-series of Command & Conquer. For example, the Troopers are very eager to fight, not unlike the basic units of those RTS games. For another example, the crewmen of Devastators are rather infatuated with the destructive effects of their heavy weapons, not unlike the crewmen of artillery pieces in those RTS games.

Then, there is the music. Most of the tracks are appropriate to the occasion. For example, there is the mix of orchestral and synthetic that plays during battles and is intended to instil a sense of urgency. More relaxed music plays when the player character is on board the Raven.

Last, and perhaps least, there is the ambience aboard the Raven in the single-player campaign. This changes from one section of the ship to another. For example, the prison chamber for the demon Corvus has an ominous hum in the background, as befitting the place for a treacherous being.

SUMMARY:

Dragon Commander shows that Larian Studios just is not experienced at strategy games. Although there are decent designs like units with mostly sensible roles in battle, the game has merely reached the lowest bars that any competently designed war game should reach.

There is a dearth of information for the auto-resolution of battles. There is a lack of features that let the player review upcoming battles. There is only one resource that is used during battle. Battles are designed to be concluded quickly with little time or opportunities for complex strategies.

Narrative-wise, the story in Dragon Commander is a convenient throwaway, complete with wasted characters like the half-siblings. Due to the conclusion of its story, its setting does not matter much to the canon of the stories of the other games that would chronologically come later. At best, it gives Larian an excuse to include things like arcane zeppelins, passing them off as reverse-engineered lost technology.

Perhaps the most contribution that the story would have to the Divinity franchise is the near-retcon introduction of the other races, especially the Lizards. These would establish the foundations for the backstories of the Original Sin games.

Overall, Dragon Commander is at best just there to show that Larian can do something other than Western RPGs. The game itself is merely decent at executing whatever individual gameplay system that it has. It is not boring and is fun sometimes, especially in its implementation of the Dragon Knight. Yet, there had been games that have done what it did already and did them better.