Essentially open to interpretation, as with any artistic expression, its an aesthetic paradigm in contemporary gaming

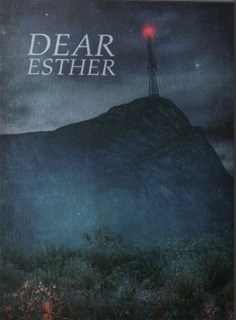

To review a game likeDear Estheris a difficult task because, on the one hand, it is in many ways a purely aesthetic game: one interacts by movement alone, slowly progressing along a generally linear path. On the other hand, the aesthetics themselves involve a technical description that could easily make the experience of play out as its skeletal components, robbing the descriptive terms of their power.

With that in mind, taken separately, each ofDear Esther's component pieces stand up very well on their own. The primary (in-game) interactivity takes place via the players movement. Environmental designs guide the player through a course of sorts, which passes by numerous events and objects. Certain of these spark a well-voiced narration that, though when put together reveal a sort of meaning for the encounters you have, on their own bend towards the poetic, relying as much on the sense of the words and word combinations as any determinate signification (ie, narrative writing). Movement is smooth and almost surreal. There is no 'running': movement has been slowed in a way that requires the player to take it all in. The is also no physical self to perceive – footsteps are heard only softly – and the camera flows up and over obstacles as if afloat. This lends the player's perspective a dream-like quality which dovetails well with the contextual environment that builds up around you.

While not technically excellent, or no more so than the Source engine the game is built from,Dear Estheris visually exceptional. The environment feels hand crafted; each rock unique, the physical landscape sweeping from beaches up to plateaus authentic, lending a realism to the exploration that counters moments which seem to leave reality, giving them additional weight. As much of what the player encounters involves remnants of past events, it is especially impressive thatDear Estherachieves a strong sense of a time having already past, now seen as having accumulated the environment's changes. Furthermore, the level design despite its general linearity does an excellent job of pacing. There always seems to be a sight or event hidden around the corner or seen from a distance, continually drawing the player along.

Even more impressive, however, is the sound design and score. Blending the environmental sounds of a lonely northern island with instance-initiated gentle but urgent musical scores, the sound easily sweeps along the player. The shifts in music and tonality are such that they create a sense of ascribed meaning to the events as they unfold, though on a repeated playthrough will underline different moments based on your different movement through. The score's effectiveness is helped by a rather wide variety of instrumentation – from piano, violins, and cellos to electronic noises and pulses. The ambient sounds are equally engaging. From the wind to the waves, the sound does a superb job of localizing the player, compounding the sense of reality which anchors the game's otherwise unreal sensibilities. Finally, the voice acting itself performed by Nigel Carrington is just outstanding. Occurring repeatedly in 'instances' throughout the game, the narrator's lines are delivered authentically and with purpose, never melodramatically, and in such a way as to build on each other, like a spoken poem.

Taken as a whole, each of these components come together for a special and perhaps profound experience. The joy of play is as much in the soaking up of the aesthetics as it is putting together bits and pieces of notes and objects and senses to create a meaning throughout one's time. Yet how does one ascribe meaning to a chain or series of chance events but by making each event necessary?Dear Esthereven intimates a sensibility which is almost 'meta' in regards to itself, though never in a distracting or noncontexual way. In fact, most of the interaction withDear Esthereffectively happens at this secondary level between the player and the game, rather than through the player's character who is essentially a blank slate or purely perceptual organ. In other words, much of the interaction is by way of the player's own interpretation of the unfolding events. It is not unlike the experience of a game likeMystbut is certainly not 'puzzle' oriented, and therefore more essentially open to interpretation, as with any purely artistic expression.

Put simply,Dear Estherwould fit right in at any contemporary art installation. Certainly, what the player 'gets' out of it or even if the game is convincing will depend to a certain extent on one's disposition. That being said, the aesthetic excellence of the game and the way in which the scattered meanings are woven together ought to be enough to give even the action-only gamer pause. Quality speaks for itself, andDear Estherhas it in spades. By far the biggest drawback is the brevity of the experience, which clocks in at around an hour or so. If you're ok with a one-time only experience that will stay with you long after, however,Dear Estherdeserves all the time it has to give you.

. . . .

"We are not like Lot's wife, you and I; we feel no particular need to turn back. There's nothing to be seen if we did. No tired old man parting the cliffs with his arms; no gifts or bibles laid out on the sand for taking. No tides turning or the shrieking gulls overhead. The bones of the hermit are no longer laid out for the taking: I have stolen them away to the guts of this island where the passages all run to black and there we can light each others faces by the strange luminescence."