The Return of Stealth

We speak to Mark of the Ninja lead designer Nels Anderson about why stealth games are cool and why developers have such a hard time making them.

One of the most oft-cited gripes of gamers bemoaning cross-genre pollination in the game development industry is that genres like stealth are becoming increasingly ignored in favour of games composed of borrowed elements that sacrifice authenticity in favour of player choice.

Stealth purists are particularly adamant that bona fide stealth games are becoming increasingly rare. Of those that survive, they argue that few measure up to the games that helped define the genre, from Metal Gear and Thief to the original Hitman and Splinter Cell games. Indeed, the race to create games that offer not just one particular playing style but a multitude of styles catering to different tastes has contributed to the decline of pure stealth; these days, you're more likely to find games that offer stealth as an option among many, rather than as the dominant or exclusive way to play.

But while some developers in the triple-A space argue this is the way to keep the stealth genre from stagnating, it seems not everyone is ready to give up on stealth just yet.

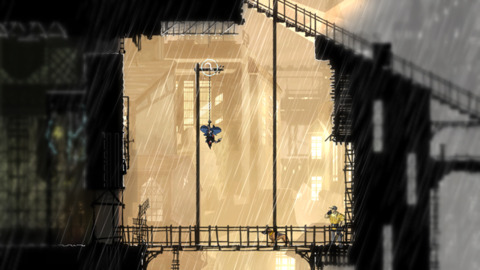

Mark of the Ninja is an upcoming Xbox Live Arcade title (to be released September 7) that will aim to put a new spin on stealth, thanks to Vancouver-based Klei Entertainment and its trademark 2D art style (see Shank, Shank 2). According to the game's lead designer, Nels Anderson, Mark of the Ninja is very much a stealth game that doesn't cheat when it comes to abiding by the rules of the genre.

"It's not an action game where one can occasionally sneak up on an enemy," Anderson told GameSpot. "At its heart, this game is about perceiving the environment, formulating a plan, and executing it. Thematically, that's what Ninja is really about: the interplay between strength and vulnerability."

Mark of the Ninja follows a ninja whose clan has survived the sengoku jidai, the country's warring states period, with the aid of an exotic flower whose leaves produce a tattoo ink that imbues the wearer with powerful abilities (heightened senses, fast reflexes, increased strength, and agility) but also slowly drives them mad. The game's story was written by freelance writer and co-founder of Kill Screen magazine Chris Dahlen, who also contributed to the 2011 Facebook version of Where in the World Is Carmen Sandiego? researching and writing most of the game's 3,000-plus location clues.

In contrast to Shank (which Anderson says was "unabashedly about the gameplay"), the Klei team wanted Mark of the Ninja to have a deeper tone and atmosphere, one that would complement the gameplay. After putting an ad on Craigslist, Anderson found himself a couple of willing playtesters (picked out of the 300-strong group who answered the ad within 24 hours) and discovered he'd been right all along.

"One of the first people we had come in started talking about one of the later levels in the game, and the way he described was almost word-for-word what Chris and I had wanted to do with the tone. It was a great moment."

But it's the 2D aesthetic that Anderson hopes will make Mark of the Ninja really stand out. Klei has already proven itself in the 2D space, giving Anderson and his team the freedom to experiment with design elements that would not have worked with an added dimension. For example, Mark of the Ninja employs a visual noise radius, allowing players to see how far they can travel without altering nearby enemies.

"2D allowed us to be more stylized. I think broadly games could do with more diversity in aesthetics, and I think that's the broad appeal for a lot of people. That's why people like 2D. I think this game allows more people to 'get' stealth without alienating those who are already fans of the genre."

While Anderson says there are a number of different ways to approach situations in the game (from slow and steady to fast and precise), the game's mechanics are completely grounded in stealth: you have to do it to be successful. You could be sneaky and not kill anyone, or you could be sneaky and kill people, but you can't go through the game simply punching people in the face.

A stealth game where players can decide how brazen or discreet they can be, and can make their way through the game without killing a single enemy? Sounds familiar. (Also this, and this.)

"There's a hilarious coincidence between Mark of the Ninja and Bethesda's Dishonored," Anderson says. "But aside from the 2D thing and production quality (you could make our game 100 times over with Dishonored's budget), the biggest difference between the two games seems to be the approach to core stealth mechanics."

Anderson says Dishonored's approach to stealth is ambiguity: for example, creating a gradient in instances where players are concealed, the boundaries of which can be tested only through trial and error (that is, keep moving forward until enemies spot you). By contrast, Mark of the Ninja relies on very explicit stealth mechanics, where perception relies on three things only: light, darkness, and noise. Players are either in total light or in total darkness, and the protagonist's appearance changes to reflect which state he is in. Finally, there's the aforementioned visual noise indicator.

"Our intention was to have no ambiguity. Not that the other way is bad, but it becomes a system that people have to understand, and that is going to require a lot of experimentation. We wanted to make all the things like that completely transparent."

Anderson himself is a fan of stealth--that much is clear. But he isn't quick to judge developers who steer clear of the genre, which he believes is tricky to navigate with disastrous consequences if not executed correctly. For example, he feels stealth doesn't really work in all those games in which it is simply an option rather than the main focus of the game, because there are too many systems working together. For stealth to really work, every single aspect of a game, from level design to art to narrative, has to pull in the same direction.

"Even though I like stealth games, I get how they can be off-putting," Anderson says. "The power dynamic is all about the player being weak when they're not in their element. But to really understand how the game works, players have to take risks. And while some people like taking risks, some don't. So they stay away from stealth, especially when it's not implemented very well."

Stealth games offer a fundamentally different experience than other character-based games, which is perhaps what makes them so interesting to developers like Anderson. In stealth, players always have to think a few moves ahead, surveying the situation and working out cause and effect beyond more simple and immediate tasks like killing an enemy or working out how to get across a platform.

"From a design point of view, it's really hard to do stealth, and that's why there aren't that many games dedicated completely to it. If every single aspect of production is not pointing in the same direction, it becomes really difficult. I replayed all of Thief II before we started this game, and reading the postmortem, the developers said the challenge was that all aspects of the game had to be working together before they could even know how the game played. We found this to be true too."

While developers and audiences may not always agree that this is the most entertaining and rewarding way of doing things, Anderson argues that more games should challenge players the way that stealth games do.

"There's a distressing trend where certain developers don't really trust the audience. They see people struggling with a game and decide to make it simpler by putting a giant golden line that points players to exactly where they're supposed to go, or not trying to do anything too ambitious with the characters or the tone, or just telling the same power-fantasy over and over again. All this stuff doesn't treat the audience like they're smart, thinking people that can understand things."

Anderson argues that the gaming audience should be trusted to figure things out for themselves and allowed to engage with games with the understanding that there is no right or wrong way of doing things.

"It's about having trust that the audience will approach the game in a way they want to, and you can't ever force it to not be that way by putting up barriers or making things painfully explicit. I don't think anyone really wins in that scenario."

Mark of the Ninja will be released on September 7 on Xbox Live Arcade.

Got a news tip or want to contact us directly? Email news@gamespot.com

Join the conversation