So You Want To Be An: Artist

Find out what it takes to be a successful artist in the game industry from some of the most accomplished video game artists around.

Artists in video games start off just like any other type of artist: they learn about color, composition, and famous paintings in stuffy old museums. Then, somewhere along the way, a love of art meets a love of technology, games, or animation, and a new type of artist is born.

There are many different kinds of game artists and many different ways for them to express their art in video games. We sat down with six video game artists who've worked on interesting-looking and beautiful recent games to try to find out what makes them tick. We asked them how they got to be where they are, what their interests are, and about some helpful tips they might be able to provide for any aspiring video game artists out there.

Though comparing the artistic style of any two of these games might be like comparing Marvel comics to a Monet, these game artists do have several things in common: a passion for their profession, a good sense of composition, and the knowhow to pull it all together for a video game.

Maybe you've asked yourself whether video games are art or not, so this feature story might help you answer to your question for yourself. At the very least, most of us can agree that games contain artistic elements; that there are special brands of artfulness and skill that video game artists use in their craft--arguably just as much skill and execution as any other artists in any other medium need to succeed.

After you're done reading this piece, don't forget to take a look at our previous feature story, "So You Wanna Be A: Game Designer," discuss what you read here in the feature story forum, and stay tuned for future editions of "So You Want to Be A:" right here on GameSpot for more insight into what it takes to develop games.

How did you become a game artist? Can you tell us about what path you took? Did you ever think you'd end up as a game artist?

How did you become a game artist? Can you tell us about what path you took? Did you ever think you'd end up as a game artist?

Lorne Lanning: I figured out that games were a big part of the future, convinced Sherry McKenna to raise the money with me, and we started Oddworld Inhabitants. I had never worked on a game before Abe's Oddysee.

I attended the School of Visual Arts in New York City and started off as a photo-realistic illustrator. After that, I moved to the West Coast and went back to Cal Arts, and studied film and motion graphics, visual effects, and computer animation. Then, I moved into film, commercials, and theme park simulation attractions with computer animation. I started as a modeler (back in the mid 80s!), worked up to lead technical director, became an art director, and then had a short-lived period as visual effects supervisor before starting Oddworld.

Actually, I didn't see it coming until about 1990 when game technology on arcade machines started indicating what was going to happen with console gaming.

Shuhei Kurose: I've always liked drawing pictures, in particular manga, ever since I was a child. I got carried away drawing pictures, and before I noticed, I ended up in this industry (it was that kind of era). I didn't intend to become a game artist at first, but I always wanted to have a job drawing pictures.

Levi Hopkins: I always dreamed of being in the gaming industry, but I was never quite certain how to go about getting a job [there]. After a few years of floundering around while inspecting cherries for the state of Washington, I finally went to art school. Fortunately, I met some fellow artists there who were beyond dedicated. We pushed each other daily until our minds and arms were jelly. With their help and motivation, I was able to get a job in the game industry. Oddly enough, those same friends work with me now at ArenaNet.

Yoshizumi Hori: After I graduated from college, I became a businessman. However, I changed my mind and went to CG school for half a year. Then I joined Capcom. I didn't expect that I was going to become a game artist. I thought I was going to work at a TV station or work on commercials.

Naoki Katakai: Having been impressed by the CG I saw in movies such as Jurassic Park, I was directed to a career working on CG for television. This ultimately led to a job at a game company that made a lot of CG cinematics. In the beginning, I didn't really think about making games for a living, as I was more interested in doing cinematics. But after a while, I understood the excitement associated with working on a game and have focused a lot more on creating "art" within the bounds of game creation.

Lee Dotson: I've always loved drawing and have spent countless hours doing art and programming for my own games. In high school, people would ask if I was going to art school, and I'd look at them like they were crazy. I grew up in a small town in Georgia in a blue-collar family; to me, those sorts of jobs were what real people did. So, it never occurred to me that making art for games was an option until I came across a course catalog for the Savannah College of Art and Design. I think I must have read the course descriptions for their computer/sequential art programs more than 100 times, because I simply couldn't believe that there was a place where art was a real course of study and not just an elective.

"Art was my first love. I was fascinated by the art used to define the worlds in games."

-Shuhei Kurose, Artist - Namco

Which of these was your first love: games or art? How does your current job tie in with your interests in art?

Which of these was your first love: games or art? How does your current job tie in with your interests in art?

Lorne Lanning: Games are fun, and they hold great potential, but so far, game story content is largely uninspired and almost entirely void of social reflection and criticism. Our Wal-Mart world spawns far more useless entertainment than we can shake a stick at, so it's refreshing on the occasions when we experience more quality and contemplative stories being told. Inspirational art that changes one's perception of the world we live in...that's what we need more of and that's what personally drives me.

It's inseparable. Whether working on film projects, game projects, or writing scripts, the goal is always the same for me: creating interesting worlds that reflect interesting and timely dilemmas that our own world is facing and always trying to portray these worlds in new and interesting ways, which can end up being something beautiful when experienced by the end user, even if the content is dark in nature.

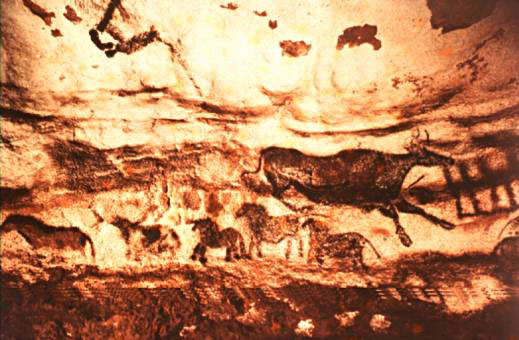

Shuhei Kurose: Art was my first love. I was fascinated by the art used to define the worlds in games. One of those games includes The Tower of Druaga, which has influenced me heavily. I feel that I want to draw pictures and create a cool world, and this position allows me to do just that. Furthermore, I am gaining more skills and knowledge while getting paid at the same time, so I'm really happy.

Levi Hopkins: When I was a young kid, my first love was gaming. I pretty much played every game that came out on the early consoles. At one point, I even had an envelope with about three months' worth of yard-work money in it just so I could buy Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles for the NES. I also remember selling all my Transformer toys just so I could get the original NES hockey game. However, as I've grown older, art has become my true love. Luckily, my work involves creating art for games, so I feel pretty fortunate that I don't have to choose between my two passions.

Yoshizumi Hori: My first favorite love was art. This job affords me a lot of freedom to work on screen composition and color adjustments.

Naoki Katakai: I have always wanted to work at a job where I can create some form of art. If it wasn't for the fact that I played Nintendo games for hours on end as a kid, I don't think I would have ever considered the game industry as a career choice. So based on that, my early appreciation for video games has more to do with why I am at Clover Studio.

Lee Dotson: I'd have to say monsters were my first love. My father took me to see American Werewolf in London when I was four years old, and even though Mom pulled me out of the theater after the first really gory death, I've been hooked on them ever since. From there, it was just natural that I got into games and comics, since they generally had lots of monsters.

On my own time, I generally like to work on character portraits that use a lot of clean lines, soft colors, and sweeping design elements to help fill out the composition, like you might see in a lot of art nouveau pieces. I usually do these pieces as a change of pace from all the flayed and gibbering masses of flesh that constitute many video game monsters. To me, they're just different aspects of my personality, and I really enjoy working on both for what they are. I don't think you can really appreciate something horrific if all you ever see are horrific things--just as you can't appreciate beautiful things if all you ever see are beautiful things.

Tell us about the process of how you create art for a game project. What's a typical day like for you? What media or software programs do you use?

Tell us about the process of how you create art for a game project. What's a typical day like for you? What media or software programs do you use?

Lorne Lanning: I haven't actually painted or done any serious drawing in years. Typically, I would work with the talented artists at Oddworld and help to shape a vision cocreatively.

My main tool was the Avid editing system and a digital camera. The camera would enable me to snap references anytime and at any place, and Avid was a great way to piece together ideas that would be useful to communicate to a larger team.

Shuhei Kurose: It all depends on how imaginative the director is at grasping the concept and expressing the game's "world setting." However, it can be dangerous to create a world setting all by yourself without listening to the advice of others. The director must maintain the basic concept of the world setting while trying to get this across to the team (this is the hard bit) and receiving their feedback. It's OK to have a general concept at first, but it's important to bring these ideas together quickly, otherwise things may start to go wrong. In other words, the director has to have a clear vision of the concept.

An idea, which may be better than the original concept, may arise, and it's the director's responsibility to decide in which direction the project should continue. As we continue this process, the previously vague general concept becomes clearer. It's difficult up until this point, but the project progresses more smoothly hereafter. The processes involved in making a game revolve around the gameplay and the needs of the player, but recent games have shown that it's the art that makes the game.

My main job is graphic design, but this time around, I'm in charge of art direction and the overall direction of the project.

I use programs such as Maya, Photoshop, Excel, and so on.

Levi Hopkins: A typical day for me would most likely involve getting a high-level environment concept from my art director, Daniel Dociu. Next, I stare at the concept in pure panic, with absolutely no idea how we're going to pull it off in Guild Wars. Then, I open up 3D Studio Max to start modeling the concept. Hopefully, a little while later I'll have a 3D mesh that's given the OK by Daniel. Finally, I open up Adobe Photoshop to paint the textures for the prop. Once this is done, I check the prop into Guild Wars and start the whole process over again. It tends to be exciting and stressful at the same time.

Yoshizumi Hori: Most of the time, I go back and forth between Maya and Photoshop. And now that I can adjust colors and other things within the game engine itself, it's even more convenient.

Naoki Katakai: I start off by making rough concept sketches of stages. These sketches are really for my own use and would probably be pretty confusing if anyone else ever saw them. But I take them and think about the "space" and camera work that could show off the environment better. So the beginning of the process is about coming up with an image and deciding on a direction for the area I want to create. Once that has been determined, I start creating the 3D space by using Autodesk Maya. I firmly believe that with the state of 3D games, environmental artists cannot create anything without solid tools.

However, there's more to creating an environment than just modeling and texturing. I try to imagine how the player is going to travel through a particular space, how the camera will move to show it off, how necessary information will be visible onscreen, and so on. I'm constantly thinking of how the space will look from the player's point of view. Then, there's the creation of a focal point in an environment. It's not necessarily effective to make content for every possible angle. You have to think about how to create a natural flow to the stage and focus your efforts into what the player will see.

Lee Dotson: I work on a lot of different aspects of the art pipeline, so what my day is like can vary a lot depending on whether I'm modeling, texturing, doing concepts, or collaborating with programmers on a way to accomplish a needed graphics technique.

Regardless of what it is I'm doing, I usually start by digging up references. So, for example, any time I start texturing the suits of armor for the Knights Templar, I fill one of my two monitors with pics of stained glass windows, priestly robes, and other sources of religious iconography to give me a point of reference. From there, I'll go into Zbrush and do a quick sketch over the entire suit to figure out how all the ornamentation is going to fill the body. I then check to make sure that each piece features something interesting, since the player will be picking up all the pieces of the suit individually. Once I've determined my overall layout, I'll go into Photoshop and start polishing the sketches, while periodically popping back and forth between Modo, Photoshop, Zbrush, and our in-house tools to inspect and adjust various aspects of the finished product.

"There's more to creating an environment than just modeling and texturing...I'm constantly thinking of how the space will look from the player's point of view."

-Naoki Katakai, Artist / Capcom

Making games is both a creative and a collaborative process. Tell us about how your art makes its way into a final game. Is there a lot of compromising, revising, and starting over from scratch?

Making games is both a creative and a collaborative process. Tell us about how your art makes its way into a final game. Is there a lot of compromising, revising, and starting over from scratch?

Lorne Lanning: I write the stories, direct the project creatively, and do many of the voices, but ultimately, the art that is visible at the end of the project came from the artists on the team. I guess the only thing that I do that physically lasts into the final product is the voices.

Shuhei Kurose: There are a lot of compromises to be made. However, they are for the better, so I guess you can't really call them compromises. As you know, the project that I'm currently working on is Me & My Katamari, which is the third game in the Katamari series. The interpretation of the world has already been established, and I felt that it was important for this game to stick to the previous games' roots while delivering something new. The team and I have discussed various ideas and suggestions without straying from the main concept. However, the most important thing is to "have fun!" If you don't then work can be hell.

Levi Hopkins: For the most part, I never have to start over from scratch on a given project. The reason for this is that I'm constantly in touch with ArenaNet's art director, designers, and level artists. I'm sort of guided to the correct result rather than blindly attempting to create art for Guild Wars on my own. Once I've run the gauntlet with a given project, I just check it right into Guild Wars. Thanks to ArenaNet's gifted programmers, artists are literally able to see their creations within the game in a matter of seconds. Being able to constantly check your art at any given phase in the process really helps to stop unforeseen problems.

Yoshizumi Hori: I get to know the characteristics of the hardware first. Then, I create something that is double what the specs can handle. Then I think about how to make it work on the hardware. I do not compromise, but I think the balance between art (visuals) and game (playability) is very important.

Naoki Katakai: In order to make art for a game, you have to think about the flow of the game at all times. There are many elements--such as how the player gets around the environments and how the camera system works--and you have to take all of this into consideration. But at the same time, no matter how much attention you put into it, problems constantly arise that you could have never predicted. Good level design happens when a great environment meshes well with the game content. As an artist, of course there are things you don't want to change. But you have to compromise and make everything functional to fit within the limits of the game. Absolutely everything gets changed or edited in some way or another. Compromising, revising, and editing are all part of the daily creation process.

Lee Dotson: Making art for games is all about compromise and revision and, sadly but occasionally, starting over from scratch. A good example of a compromise that I make is in the portrayal of female sexuality in video games. I've always hated that male characters are typically covered from head to toe in layers of armor, while their female counterparts are equipped with nothing more than a chain mail bikini. It doesn't make any sense if you're even vaguely going for realism, and from a design perspective, it's been so overdone that the characters become completely forgettable. I've had this argument with many other developers over the years, and while some share my view, others do not. Many times those people that haven't agreed with me were the project lead or art director, so I've had to let the argument drop and do my job, because that's part of being a professional and part of working on realizing the team's vision of the game, as opposed to just my own.

Fortunately, starting over doesn't happen too often, but on more than one occasion, I've modeled/textured a character that was based off an approved piece of concept art, only to find out that the character was really supposed to be completely different, long after the work was completed. Sometimes things will also get cut for reasons that have nothing to do with the art process at all, but rather because of scheduling problems in other parts of a project. While working on Anachronox, I had textured more than 80 monsters that never made it into the final game!

Please cite two games--one game you've worked on and one game you haven't worked on--that you felt had a very effective art style. What was so good about the art in each game?

Please cite two games--one game you've worked on and one game you haven't worked on--that you felt had a very effective art style. What was so good about the art in each game?

Lorne Lanning: Abe's Oddysee broke a lot of boundaries when it came to matching cinematic storytelling seamlessly into gameplay, but Stranger also took it levels further than Abe had. For Abe, we were focused on raising the overall production design level for what we expect in a game. We were also using film production designers, and there wasn't much of that going on at the time.

I thought Ico had the most cohesive and beautifully balanced art in a game that I had ever seen. Shadow of the Colossus took it even a few steps further. Before that, Myst was pretty inspiring in its production design.

Shuhei Kurose: The companies are different, but I've worked on a certain racing game and a certain fighting game. A game that I didn't work on that I think has a good art style is the GameCube title The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker. Both types of games feature anime and manga-style art, but feel "real" because a lot of thought has been put into the way the world settings are portrayed.

Levi Hopkins: I'm currently working on Guild Wars: Factions. I feel we have an effective art style due to our incredibly talented art team and a set of tools that allows us to work quickly. We try to make things believable, fantastical, and different at the same time. Super Monkey Ball is a game I didn't work on but felt had an effective art style. There's just a lot of character that was pulled off when you put a monkey in a little ball.

Yoshizumi Hori: One [game I've worked on] is Resident Evil 4. I used as many polygons in this game as I could. For example, all the tree branches and elements like that are made up of polygons. I guess you could call Resident Evil "polygon art." My other choice would be Xevious. It has a consistent, mysterious, and beautiful world, as well as a special language, and all that. You can attack objects on the ground; there are hidden characters, music, and sound effects, which really stick with you. At the time, it was all cutting edge (refreshing, fresh, innovative, and so on).

Naoki Katakai: Biohazard [for the GameCube] was the first title where I was responsible for the environment art direction. I enjoyed working on the title and was pleased with how it turned out. I think I was able to add my own style to create a convincing atmosphere. I did not work on The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker, but drew some inspiration from it for Okami. Looking at gameworlds created with new, unique visual styles is very enlightening.

Lee Dotson: I think with Unreal Championship 2, we did a really good job of preserving the colorful feel of the classic Unreal Tournament [from 1999] while giving the overall art style a bit more consistency and a higher level of overall polish. All the visuals were so over the top. Everything glowed, shimmered, and distorted to the point that it was almost like being in a sci-fi candy shop, which I thought was a lot of fun considering how many games are set in the "oh so grim" future.

"The most rewarding part about being a game artist is being surrounded by people who will push you in your craft."

-Levi Hopkins, Artist / ArenaNet

Shadow of the Colossus has got to be one of the most beautiful games I've played recently. They did a fantastic job of giving the player a sense of scale when looking across grand vistas and at the game's many lumbering and flying colossi. The game really uses the whole screen as a composition, instead of just throwing together a lot of characters that are cool individually. In SOTC, it's the mountain that's important, not the rocks that make it up. I think their restrained and well-placed detail really helped them pull that game off.

What's the most exciting and rewarding part of being a game artist? Seeing your creations come to life? Working with your team? Creating something new?

What's the most exciting and rewarding part of being a game artist? Seeing your creations come to life? Working with your team? Creating something new?

Lorne Lanning: It is probably watching the art actually come to life in animations, and then when those animations meet good controls and find their way into fully rendered backgrounds. Once all of the pieces come together on something that hasn't quite been done before, that's usually the high point.

Shuhei Kurose: Of course, all of the above are exciting and rewarding, but I gain the most satisfaction from knowing that I've developed my skills and ideas as a game artist. I find that you become positive by saying to yourself that your actions are for self-development, which in turn is for the benefit of the entire project.

Levi Hopkins: The most rewarding part about being a game artist is being surrounded by people who will push you in your craft. Every day, I see one of ArenaNet's artists creating something I feel I could never do, and it pushes me to work harder. Another rewarding aspect of being a game artist is the ability to play a serious game of Desert Combat at lunch. Nothing beats hopping into a Humvee with a fellow artist and riding off into a sunset filled with rocket-propelled grenades.

Yoshizumi Hori: I always think about whether the players will enjoy the worlds we create. The best part for me is if players have fun playing our games.

Naoki Katakai: It's wonderful to see the world you created living and breathing as people walk through it in the game. You created a brand-new world and get to see it come to life on the screen. I think this satisfaction is unique to games and can't be found in movie or video production.

Lee Dotson: I'd have to say that the collaboration with so many other talented individuals is really my favorite part of working in the games industry. I can't count the number of times I've walked over to someone else's desk and been so blown away by what they were working on that it made me want to work even harder to make sure everything I was doing was just as cool. It's also great to have people you trust, who can bring in an outside perspective when a piece isn't really coming together or when there's just that "one thing" that's missing. I definitely think I've learned far more from my peers over the years than I did in art school, and as long as I can keep learning, I'll probably keep doing game art.

As game technology advances, it's becoming much harder and more time consuming to make a visually impressive game with high-resolution textures, more environmental objects, facial animations, and so on. What are your thoughts on art and art assets in games in this and the next generation?

As game technology advances, it's becoming much harder and more time consuming to make a visually impressive game with high-resolution textures, more environmental objects, facial animations, and so on. What are your thoughts on art and art assets in games in this and the next generation?

Lorne Lanning: Game art will get a lot better looking, but it's still lagging behind CG film and will be for the next generation as well. Eventually, we won't be able to tell real-time CG from pre-rendered CG. The differences will become more and more difficult to detect, and once reality is achieved well in real time, then, of course, more will always be able to be done in pre-rendered art, but the audience will have a much harder time detecting which is which.

Shuhei Kurose: It's usual for games this generation to look "good," but there aren't that many games that look "real." Even with improved textures and resolution, the visuals in some games seem incomplete. As the resolution increases, the imperfections in the visuals become more apparent, so you have to go into more depth as to what "real" is. This can be said for both photo-realistic visuals and the opposite, vector graphics. All the things that you feel and experience in daily life are probably the key to understanding the true meaning of "real." A lot of information can be found on the Internet, but it is also important to touch and feel the real thing.

Levi Hopkins: Everything is going to take a lot more time. Quite frankly, I'm freaking out at this very moment just thinking about it.

Yoshizumi Hori: Of course it is necessary for us to learn the new technology, but I am very confident that we are still here because fans bought and enjoyed the games we've made over the years. So regardless of the new technology with the next-gen hardware, I want to continue making the same kinds of great games we always have. Of course, we do not intend to run away from the trend of making things more realistic, but at the same time, the most important thing is the balance between the art, the playability as a game, and reality.

Naoki Katakai: One of my main work goals is to "wow" people. Impress them with how beautiful, real, or scary the gameworld can be. When the specs of new system hardware are released, you realize you can do more with powerful hardware and more production time. But I think you're wasting the capabilities of the hardware by simply aiming for a more realistic portrayal of the "real world." You have the power to create a brand-new world, and I want to make something new and really impress people.

Lee Dotson: I think one of the biggest stumbling blocks that I see a lot of people tripping over as we transition into the next generation is that we've been so limited in what we can make that the question has always been "can" we do something and never "should" we do something, or even "does it even matter to the game?"

Game art should be the servant of the game itself, and when we're creating that art, we should really be focusing on what is going to have the most impact on the player. I've seen a lot of artists get so fixated on making the most intricate, high-poly model ever that they lose sight of what the asset in the game is meant to be. If it's a mailbox, then it doesn't need to be the most intricate mailbox the CG world has ever seen, unless that mailbox is really important to the game. If you're working on a real-time strategy game, does it really matter whether or not the units have normal-mapped pores or facial expressions that you can barely see?

There's also the question of how detail affects the player's ability to discern what's important in the world and what's not. When working on a painting, you guide the viewer around the piece from one area of interest to the next. If motion of the piece is the important part, then looser strokes are used, because that's what the viewer should be focused on. In this way, we can choose to either confuse or help players move through the world by having the most interesting objects in the world be the ones that are the most important to them.

"Study the fundamentals. Knowing how to use Photoshop or Maya does not make you an artist."

Lorne Lanning, Co-founder / Oddworld Inhabitants

Do you have any advice for aspiring game artists out there? What kind of training and preparation would be good for game artists in this day and age?

Do you have any advice for aspiring game artists out there? What kind of training and preparation would be good for game artists in this day and age?

Lorne Lanning: Study the fundamentals. Knowing how to use Photoshop or Maya does not make you an artist. You need to have solid understandings of form, volume, perspective, lighting and composition, color theory, and so on. It's sad to see computer operators consider themselves artists when they actually only know how to use tools and know very little about creating images that are compelling to look at. Focus on the traditional basics, and the computer tools will be easier to learn.

Shuhei Kurose: It goes without saying that "everyday training" on a technical level is necessary, and as I said before, it would be beneficial to constantly train your senses and feelings in everyday life. There are various ways in which you can train your senses--by looking and touching, as long as you have a feeling of observation. I feel that a game artist is in the position of providing people with virtual reality experiences, so it's important for them to become the leading expert in senses/feelings. In virtual worlds, that's no small feat. I feel that in some ways, games have been exhausted of ideas, but personally I don't think imitating or copying is a bad thing. Taking out the essentials and creating better imitations result in an original piece of work, in my opinion.

Levi Hopkins: My advice for aspiring game artists is to really dedicate yourself to improving your traditional art skills. Draw every day, all day, until you start seeing things differently. I find that my 3D artwork improves with the more 2D artwork I do. Draw nonstop from life so you can come to understand how things work in the real world. Once you begin to understand things from real life, you can create believable fictional environments, characters, and creatures. I seriously can't stress enough how important it is to really focus on traditional art skills. Most anyone can be taught a 3D program, but having an eye and the hand to create amazing art comes from a serious dedication to traditional skills.

Yoshizumi Hori: I feel that all the graphics of more realistic games are all going in the same direction. Of course, it's my job to make graphics better, and I think good graphics are a big plus. However, I think it is important to avoid focusing simply on the technology behind the games and really think about what we could make that gamers would enjoy. That's what I think is really important.

Naoki Katakai: With making games, the development process is very long, and you have to be prepared and willing to compromise, negotiate, edit, and take and follow orders. But even so, it's a very fun and rewarding job.

Lee Dotson: I think the two biggest suggestions I can give to any aspiring game artist out there would be to be persistent and to be willing to go where the work is. I was rejected at least a dozen times! Three rejections were at Ion Storm, where I was incidentally finally offered my first industry job. Every time I got rejected, I threw out the bottom 80 percent of my portfolio and made a new one that took into account any criticism I was lucky enough to have gotten from my last rejection. When I did finally get that job, it was in Dallas, Texas--a place I'd never been and never particularly wanted to live, but that's where the work was. Without that break, I'd never have made it to any of the other places I've worked.

That does it for GameSpot's "So You Want To Be An: Artist." Check back in with GameSpot in the future for further interviews with game developers for what it takes to break into the business and succeed in developing games. Also, be sure to share your thoughts in the feature story forum.

Got a news tip or want to contact us directly? Email news@gamespot.com

Join the conversation