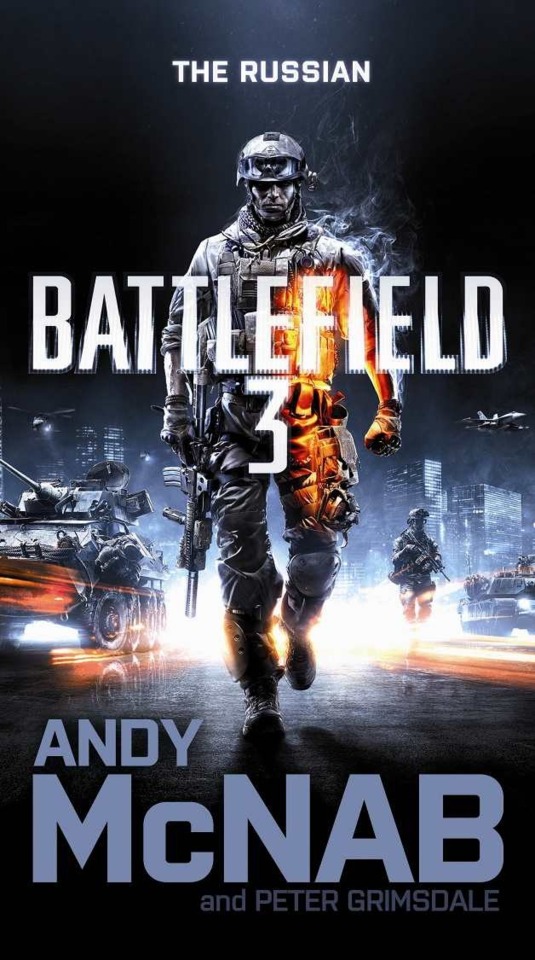

Sneak Preview: Battlefield 3: <i>The Russian</i>

Get a special early look at the first two chapters of the novel based on Battlefield 3. Warning: Contains strong language.

This is an excerpt from BATTLEFIELD 3: The Russian by Andy McNab and Peter Grimsdale. Copyright © 2011 by Electronic Arts Inc. Reprinted by permission of Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.

The Russian is scheduled to be released alongside Battlefield 3 on October 25, and it can be preordered from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

1

Moscow, 2014

Dima opened his eyes, a second of blankness before he remembered where he was and why. The call could come at any time, they'd said. It was just after three. Bulganov's voice was thick with fatigue. He told him when and where. He started to give directions, but Dima shut him up.

'I know where it is.'

'Just don't fuck up, okay?'

'I don't fuck up. That's why you hired me.' Dima hung up.

Four- thirty, a stupid time to choose to swap a girl for a suitcase of money, but he wasn't making the decisions.

'Remember: you're just the courier,' Bulganov had said, trying to swallow his pain.

Bulganov had wanted to use counterfeit, but Dima had insisted--no tricks or else no deal.Dima called Kroll, told him twenty minutes. He took a cold shower, forcing himself to stay under until the last traces of sleep were gone. He dried, dressed, gunned a Red Bull. Breakfast could wait. He gave the case one last check. The money looked good: US dollars, five million, shrink-wrapped. The price of oligarchs' daughters was going up. Bulganov had wanted to use counterfeit, but Dima had insisted--no tricks or else no deal.

Barely a dent in the man's fortune--not that it stopped him trying to beat them down. The rich could be very mean, he'd learned--especially the old ones, the former Soviets. But the Chechens had set their price. And when a fingernail arrived in the post, Bulganov caved.

Dima put on his quilted coat. No body armour: he couldn't see the point. It weighed you down and if they were going to kill you they'd aim for the head. No firearm either, and no blades. Trust was everything in these exchanges.

He handed in the key cards at reception. He'd paid last night. The woman on the desk didn't smile, glanced at the bag.

'Going far?'

'Hope not.'

'Come back soon,' she said, without conviction.

The street, still dark, was empty except for clumps of old snow. Moscow under new snow he liked: it rounded off the sharp edges, covered up the grime and the litter, and sometimes the drunks. But it was April, and the frozen remnants clung to the pavements in long, winding fortifications, like the ones they'd been made to dig at military school. The tall, grey buildings disappeared into low cloud. Maybe winter wasn't over just yet.

A battered BMW swung into view, weak lights bouncing off the glaze of ice. The tyres slid a little as it shuddered to a halt in front of him. It looked like it had been rebuilt from several unwilling donors, a Frankenstein's monster of a car.

Kroll grinned up at him. 'Thought it would remind you of your lost youth.'

'Which part?'

Dima didn't need any reminders: any idle moment and the old times crowded in--which was why he did his best never to be idle. Kroll got out, popped the trunk lid and hefted in the bag, while Dima took his place at the wheel. The interior smelled of sauerkraut and smoke--Troikas. You wouldn't catch Kroll with a Marlboro. He preferred those extra carcinogens that came in Russian tobacco. Dima glanced at the ripped back seat: a bed roll, some fast food boxes and an AK: all the essentials of life.

Kroll slid in, saw the expression on Dima's face.

'You living in this crate?'

Kroll shrugged. 'She threw me out.'

'Again? I thought you'd got the message by now.'

'My ancestors lived in yurts: see, we're going up in the world.'

Dima said it was Kroll's nomadic Mongol blood that got in the way of his domestic life, but they both knew that it was something else, a legacy of having lived too much, seen too much, killed too much. Spetsnaz had trained them to be ready for anything--except normality.

He nodded at the back seat. 'Katya has standards, you know. One look in here and she might decide to stick with her captors.' He shoved the shift into drive and they took off, fishtailing in the slush.

Katya Bulganova had been snatched in broad daylight from her metallic lemon Maserati, a vehicle that might as well have had 'My Daddy's rich! Come and get me!' embossed on the hood. The bodyguard got one in the temple before he even saw what was happening. One onlooker said it had been a teenage girl brandishing an AK. Another described two men in black. So much for witnesses. Dima had little sympathy for Katya or her father. But Bulganov didn't want sympathy and he didn't just want his daughter back. He wanted his daughter back and revenge: 'A message to the underworld: no one fucks with me. And who better to deliver it than Dima Mayakovsky?'

Bulganov had been at Spetsnaz too, one of the generation that bided its time then cut loose in the free-for-all Yeltsin years, to grab their share. Dima despised them, but not as much as those who came after, the grey, lifeless micromanagers. Kushchen, his last boss, told him,'You played the wrong game Dima: you should have shown some restraint.'

Enough people higher up thought he had done too well, too soon…Dima didn't do restraint. On his first posting, in Paris as a student spy in '81, he discovered that his own station chief was preparing to defect to Britain. Dima took the initiative and the man was found floating in the Seine. The police settled for suicide. But initiative wasn't always appreciated. Enough people higher up thought he had done too well, too soon, which was how he ended up in Iran training Revolutionary Guards. In Tabriz, near the Azeri border, two recruits on his watch raped the daughter of a Kazakh migrant worker. They were only seventeen years old, but the victim was four years younger. Dima got the whole troop out of their bunks to witness proceedings, then made them stand close enough to see the look on the boys' faces. Two shots each in the temple. The troop excelled in discipline after that. Then in Afghanistan, during the dying months of the occupation, he witnessed a Russian regular soldier open up on a car full of French nurses. No reason--out of his head on local junk. Dima put a bullet in the corporal's neck while he was still firing, tracer rounds arcing into the sky as he fell.

Perhaps if he had shown more restraint he would at least still be at Spetsnaz, in a civilised posting where he could use his languages, a reward for the years of dedication and ruthlessness, not to mention the chance to reclaim a bit of humanity. But Solomon's defection in '94 had done for Dima's reputation. Someone had to take the rap. Could he have seen it coming? At the time, no. With hindsight, maybe. The only consolation--he'd packed in the drinking and that had been the toughest mission.

The streets at this hour were almost empty, just as they used to be all day long in his childhood. Under the throngs of imported SUVs, Moscow's vast avenues lost their grandeur. There was a queue to get on to the Krymsky Bridge, where a beat-up Lada had been rammed by a Buick. Doors open, two men shouting, one wielding a crowbar. No police in sight. Two drunks staggered along the pavement, joined at the head like Siamese twins, plumes of vapour rising from them into the frozen air. When they reached the BMW they paused and stared. They were men from the past, probably no more than fifty years old, but with faces so ravaged by drink and bad diet they looked much older. Soviet faces. Dima felt an unwelcome sense of kinship, not that they would have known.

One spoke, inaudible through the glass, but Dima lip-read: 'Immigrants'. Kroll tapped him on the shoulder--the lights had changed.

'Where are we going, anyway?'

He told him. Kroll snorted.

'Nice. Residents sold the window glass so the authorities put up plywood instead.'

'Capitalism. Everyone's an entrepreneur.'

Kroll was off. 'Fact: There are more billionaires in Moscow than any other city in the world. Twenty years ago there weren't even any millionaires.'

'Yeah, but probably not round here.'

They passed rows of identical blocks of flats, monuments to the workers' paradise, now filled with the drugged and the dying.

'Tombstones in a giants' graveyard,' said Kroll.

'Easy on the poetry: it's a bit early for me.'

They parked between an inverted Volga, stranded on its roof like an upturned beetle, and a Merc, the passenger compartment burned out. The BMW blended right in.

They got out. Kroll lifted the trunk lid and reached in. Dima moved him aside.

'Careful with your back.'

He lifted the bag out of the trunk and set it on its wheels.

'Big bag.'

'Big money.'

Dima handed Kroll his phone. Kroll tapped his shoulder where his Baghira was holstered.

'Sure you want to go in naked?'

'They're likely to scan me. Besides, it will impress them.'

'Oh, you want to look like a tough guy. Why didn't you say?'

They exchanged a look, the look that always said it could be their last. 'Twenty minutes,' said Dima. 'Any longer--come and get me.'

The lift was dead, its doors half-closed on a crushed shopping trolley. Dima collapsed the grab handle of the case and lifted it. The stairs stank of piss. Despite the hour, the building was alive with the thump of rap and domestic disputes. If it came to an exchange of fire, no one would hear or even care. A boy of no more than ten came past, with the low nasal bridge and pinched cheeks that Dima recognised as foetal alcohol syndrome. The grip of a pistol stuck out of his hoodie pocket, a dragon tattoo on his gloveless white hand. The kid paused, glanced at the bag, then Dima, considering. Behold the flower of post-Soviet youth, Dima thought. He wondered if he had been right not to bring a gun. The boy, expressionless, moved on.

The metal apartment door made a dull clang as he thumped it. Nothing. He thumped again. Eventually it opened half a metre to reveal the muzzles of two pistols, the local equivalent of a welcome mat. He stood back so they could see the case. Both of the faces behind were shrouded in ski masks. The men stepped back to let him enter. The apartment was dark; candles on a table gave out a ghostly glow. The smell of fried food and sweat hung in the hot dry air.

A mask was a sign of weakness--another useful pointer.One man pressed a pistol into Dima's forehead while the second, shorter one patted him down, squeezing his genitals as he went. Dima had to force himself not to kick out. He sent a stern command to his foot, ordering it to stay on the floor while he collected all the data he could. The shorter one probably late twenties, left-handed, stiff movement in his left leg, which bent awkwardly, probably from a wound to the left lower abdomen or hip. Useful. The other, straight and tall, almost two metres, looked younger and fitter, but being a terrorist had lived on a poor diet and had neglected to exercise. The sight of their faces would have helped, but the job had taught him to assess character from movement and body language. A mask was a sign of weakness--another useful pointer. A slight tremble from the gun trained on him: inexperience.

'Enough.'

The voice that rang out from further in the gloom, followed by a low cancerous chuckle, was instantly recognisable. The room became clearer: empty except for the low table strewn with candles, a takeaway pizza box, three empty Baltica cans, a pair of aged APS Stechkin machine pistols and a couple of spare mags. Behind the table squatted a huge red plastic sofa that looked like it had come from a cheap brothel.

'You've aged, Dima.'

The sofa creaked as Vatsanyev hauled himself to his feet with the aid of a stick. He was barely recognisable. His hair was grey and ragged and the left half of his face had sustained severe burns, the ear almost gone under shiny, livid scar tissue that twisted round to one end of his mouth. He let the stick drop and opened his arms--the knobbly fingers splayed. Dima stepped forward, let himself be embraced. Vatsanyev kissed him on both cheeks then stepped back.

'Let me get a look at you.' He grinned, half his top teeth missing.

'At least try to act like a terrorist. You sound like my great aunt.'

'I can see some grey on you.'

'At least I have all my teeth and both my ears.'

Vatsanyev gave another chuckle and shook his head, his black eyes almost disappearing into the folds of flesh. Dima had seen men in all of the stages between life and death. Vatsanyev looked closer to the latter. He let out a long sigh and for a moment they were comrades again, Soviets united, brothers in arms for the Great Cause.

'History's not been kind to us, Dima. A toast to the old days?' He gave a theatrical wave at the half-empty bottle on the table.

'I've given up.'

'Traitor.'

Dima looked to his right and saw two corpses, both women, half covered with a rug--overdone, doll-like make-up on the one who still had a face.

'Who are they?'

'The previous tenants. Behind on their rent.'

They were back in the present. Vatsanyev stepped back to reveal the huddled bundle on the sofa.

'Allow me to introduce our guest.'

Katya was barely recognisable from the glamour shots Dima had been shown. Her stained hoodie almost obscured her face, which was a blotched mess, eyelids swollen from tears and exhaustion. The ragged bandage on her left forefinger was grey, topped with a dull brownish-red stain. Her blank eyes met Dima's and he felt an unfamiliar stab of pity.

'Can she stand? I'm not carrying her down those flights.'

Vatsanyev glanced at her. 'She walks and talks, and is now maybe a little wiser to how the other half lives.'

Katya's eyes focused on Dima, then her gaze moved slowly to the doorway to her left, and then back to him. He made a mental note to thank her later--if there was a later. He gestured at the case. He wanted them to start counting soon.

'You're getting greedy in your old age, Vatsanyev. Or is this your pension?'

Vatsanyev gazed at the money and nodded thoughtfully. 'You and me Dima, we don't do retirement. Why else are you here in this godforsaken shithole at this ungodly hour?'

They looked at each other and for a second the years that separated them vanished. Vatsanyev reached forward, clasped him by the shoulder.

'Dima, Dima! You need to move with the times. The world is changing. Forget the past, forget the present even. What's coming will change everything. Trust me.'

He let out a barking cough, exposing gums where teeth had once been. 'We're in what the Americans call the End Times--but not in the way they think. God won't be there, that's for sure. Three letters: P-L-R. Time to polish up your Farsi, my friend.'

They had served together in Iran during the war with Iraq, comrades and rivals. Dima had to arrange Vatsanyev's release from the Iraqis, but not before they had stamped on his back and pulled out all of his fingernails. They had even stayed in touch after the break-up of the Soviet Empire, but Vatsanyev had gone underground after Grozny fell to the Russians. Now they faced each other in a dead hooker's flat, mercenary and terrorist--two professions that were on the up.

Dima swung round suddenly. The two ski masks jumped. He bent down and unzipped the case, and with the flourish of a black marketeer presenting his booty flipped back the lid to reveal the neatly packed dollars. Bulganov wanted it all back but that might have to be Kroll's task. The ski masks stared in wonder. Good, more signs of innocence. Vatsanyev didn't even bother to look.

'Aren't you going to count them?'

He looked perturbed.'You think I don't trust my old comrade?'

'It's Bulganov's money, not mine. If I were you I'd check every one--front and back.'

Vatsanyev smiled at the joke then nodded at his boys, who knelt down and eagerly started to pull at the tightly-packed bundles. The atmosphere in the room relaxed a little. Dima noticed that a dark stain had spread from under the rug that had been thrown over the dead hookers.

The shorter Chechen holstered his pistol but the other left his on the floor by his left knee. Less than two metres away. Dima wished he knew who or what was in the next room, but it was now or never.

'I need a piss. Where's the toilet?'

Still with the gun under him, Dima aimed another shot into the groin of the man beneath him and felt the explosion as he went slack.Dima leapt forward, appearing to trip over the table which tipped it on its side. He slammed down hard on top of the younger thug who folded in on himself like a book. As he landed, Dima lunged for the pistol on the floor with both hands, found the trigger with one, racked the top slide with the other and without raising it fired first at the taller one, hitting him in the thigh. The man sprang backwards, offering Dima a better target. The bridge of his nose exploded with petals of bloody flesh. Still with the gun under him, Dima aimed another shot into the groin of the man beneath him and felt the explosion as he went slack. Without pausing, Dima rolled himself over the open case of money and across to the corner diagonally opposite the open door. Looking back, he saw the sofa was empty. Vatsanyev was bent over the upturned table trying to reach one of the guns with his stick. Dima lost a whole second as a remnant of embedded kinship stopped him taking a shot. He recovered enough to put a bullet into Vatsanyev's shoulder.

Katya was nowhere to be seen. She had to have gone into the other room. Had she taken shelter there or been pulled in by whoever was in there? He didn't have to wait long. She appeared in the doorway, head pulled back, her face contorted in a fresh convulsion of fear. Just behind her, another face half-hidden, even younger. No question who this was: the same black eyes as her father's, only wrapped in an exquisite porcelain doll's face. Dima did a quick calculation: Vatsanyev's daughter Nisha, his only child by his last wife would be--sixteen. Nisha had had the choice, could have gone to America with her mother and could soon have been heading for Harvard. Instead she was here, sucked into her father's desperate struggle. He glanced at Vatsanyev on his side, eyes open, watching his daughter on the other side of the money he would never get to spend.

Dima's eyes locked on to Nisha's. She kept her body behind Katya, gripping her captive's hair tightly with one hand while the other held a breadknife against her throat. Half a second passed. Dima had been here before. There had been younger targets than Nisha. An eight-year-old boy in northern Afghanistan wielding an AK like it was joined to him, and a girl, a trained sniper sent to assassinate her own informant father. On a rooftop where he had cornered her, the building beneath them burning, he made a last attempt to persuade her to switch sides. But she made it clear that the idea disgusted her and insisted on going down fighting.

Another half second. There were no choices here, no second thoughts, no opportunities for negotiation. Her father had been like a brother once; Dima had even once held Nisha as a baby. The best she could hope for was that his aim wasn't what it was, that his bullet would hit Katya and then they'd all be fugitives.

Dima raised his arm. It seemed to take a huge effort, as if some subterranean force field was exerting itself. Nisha was slightly to Katya's left, face half-shadowed by her captive. Dima fired wide, predicting that Nisha would dart behind her human shield, then he fired again to Katya's right, catching Nisha on the rebound. Katya crumpled forward as Nisha dropped her and fell back into the darkness. He sent a further burst into the other room, then stepping across the debris and bodies he lifted Katya into his arms.

In the sudden silence he could hear the rapid breathing of one of the Chechens. Dima turned, about to put a bullet in him, when he heard something shuffling outside. He looked up just as the apartment front door exploded. Three AK muzzles and, not far behind, three figures: faces pointlessly blackened, their helmets and body armour fresh and untarnished by action. An internal security SWAT team--famous for their ineptitude. Trying to take in the scene that confronted them, they froze. For a moment, nobody spoke.

'He's down there,' Dima said, gesturing at Vatsanyev but keeping his eyes on the men. He could hear Vatsanyev struggling to lift himself, and his wheezing whisper,'Dima, Dima, don't let them take me.'

One of the SWATs stepped forward, lowering his weapon. 'Dima Mayakovsky, you're to come with us.'

'On whose authority?'

'Director Paliov.'

'Am I under arrest?'

'No, you have an appointment.'

'Can we make it later? I'm a bit busy.'

Kroll appeared in the doorway, behind them.

'Sorry I wasn't able to warn you. Shall I take the goods?'

At the word 'goods', one of the SWATs fixed his gaze on the money. As the SWAT nudged his pal, who'd clocked Katya as part of the package, Dima swung his own weapon up into his face. The second one, weighing up whether to ditch his nice steady job for a case full of dollars, left Dima plenty of time to ram the gun into his balls.

Dima looked round at Vatsanyev and gave him a single nod. Looking back at the men, he said, 'Just a moment'. Then he looked once more at his old comrade, and put a bullet in his head.

2

Gru Headquarters, Moscow

Paliov folded and unfolded a corner of the report as he read. With two fingers of his other hand he smoothed a patch on his forehead, as if trying to eliminate part of the network of creases that was ranged across it. The pendulous folds of skin under his eyes reminded Dima of the nosebags the carthorses wore in winter on the farm where his mother once worked. The big empty desk should have been an indication of Paliov's status, but Dima thought it had the opposite effect. It made the Chief of Operational Security look small and shrivelled.

The incident at the apartment was less than two hours old, but the hastily-concocted document looked like it ran to over twenty pages. Paliov appeared to be studying every word, frowning as he read. Dima offered him a summary.

'To save your valuable time, Director, it's simple: Went in, got the girl, kept the money, shot them all. The End.'

'Vatsanyev could have been a useful source.'

'How?'

Paliov looked up from the report and glared.

Dima hadn't expected this. Typical: you sort out a mess for these people and they suddenly decide they need someone who's already been stored in the big, chilled filing cabinet with a tag on his toe. Anyhow, they'd never have got anything out of this one. Did these people never learn?

He laughed. 'If we'd lopped off his other ear?

Snipped off his damaged fingers one by one? You could have pruned every limb, and his bollocks, and served him up his own cock on a blini; he wouldn't have given you a thing. He's a Chechen for God's sake.'

'And then there's the matter of my men. How do you explain that?'

'Explain what?'

This was getting tiresome. Dima hadn't expected a medal and the massed ranks of the St. Petersburg Symphony, but couldn't Paliov at least pretend to sound grateful?

'I'm informed that they were beaten up in an unprovoked attack.'

Dima restrained himself with difficulty.'Use your imagination. After those jokers brought me here, they'd have banged the girl and vanished with the money. You should congratulate me on purging your service of corrupt elements.'

Hadn't this occurred to him? He seemed to shrink further behind the desk. Dima glanced around the office. He hadn't previously been inside the GRU's new 'Aquarium', opened by Putin himself in 2006 and thoughtfully placed within sight of the old one. No one was sure how it had got its nickname--you certainly couldn't see in, that was for sure. One theory was that it was the reputed birthplace of waterboarding. Either way, and despite this latest attempt to finesse the past, the old name had stuck.

The presence of foreign furniture and new technology was striking: an Italian chair, Apple computers, on the wall a slightly bleached print of Nattier's portrait of Peter the Great. And by the window, a plant that was actually alive. An agent repatriated after long years away might be forgiven for wondering which country he was in. But the frosted glass of the internal windows and the lingering hint of pickled cabbage in the recycled air was a giveaway.

Dima nodded at the fat file under Paliov's nose.'If that really is a report on the incident, I congratulate your staff on their creative writing. The whole thing didn't last as long as it's taking you to read about it.'

Two more goons jumped out of the Audi with a view to helping Kroll with the case.Paliov didn't respond, looked down again, continued to read. Dima wished he had managed to stop for some breakfast after all. Six dead, two in casualty, and it wasn't even nine-thirty. An armoured GAZ SUV--at least that was Russian--and an official Audi, blue light flickering on the dash, had been waiting outside when they came out of the apartment block. Two more goons jumped out of the Audi with a view to helping Kroll with the case. Kroll tried to dissuade them with a couple of punches but they didn't get the message, so Dima had to slam them against the car a few times, and in the case of the one who grabbed Katya, shut his arm in the trunk.

Dima had taken the SUV and delivered both Katya and the money to her grateful father. At least that was one satisfied customer. He had urged Kroll to help himself to the Audi. It was top of the range--heated seats and integral Bose music system, even a cute little circle of beige leather on the end of the cigarette lighter--but Kroll said it was too loud for him and besides, he said, disabling the tracker was a pain.

It had been so long since his former masters had come asking for him, it was a wonder they even remembered him.It was still dark, so Dima had turned on the sirens and the blue lights and had enjoyed a quick spin down the wrong side of the road--a metaphor for his whole life, now he came to think of it. He had thought of skipping the appointment with Paliov altogether, but a twinge of curiosity had prevailed. It had been so long since his former masters had come asking for him, it was a wonder they even remembered him. At the famed 'tank- proof' barrier, a guard waved the GAZ through without even checking who was at the wheel. A shocking lapse in security. He parked it in a space reserved for the Deputy Secretary of Paperclips or some such. Only when he presented himself at the desk and saw the pained expression on the pretty receptionist's face did he hesitate. The parking space? He was just preparing a snappy excuse when she nodded slowly towards a floor to ceiling mirror. His face was still peppered with a fine spray of blood from one of the exploding goons, the first lot.

'Sorry,' he said. 'Busy morning.'

She reached into her bag and produced a packet of baby wipes. He smiled. 'Bet they come in handy.'

'Every day.' There was a mischievous look in her large dark eyes. 'On my twins.'

For a fleeting moment he wondered whether she meant the pair of delicious breasts straining against the cotton of her shirt. Now he had another incentive to miss the appointment: a quick fuck over the desk would have more than made up for the missed breakfast. He dabbed his face and held the wipe up in tribute as he walked towards the lifts.

Paliov finished reading, took off his spectacles and rubbed his eyelids with his thumb and forefinger, as if he was trying to make what he'd just read go away. Then he turned to Dima and shook his head.

'How much did Bulganov pay you?'

'It was a favour. For old times' sake.'

'Ah, old times.' There was a mournful faraway look in Paliov's eyes as if he was recalling his first fuck, which may well have preceded the Siege of Leningrad if not the Revolution itself.

'The good old days. We must get together some time and reminisce over a few bottles.'

Another man entered without knocking: slim, wiry, taut frame, early forties, tailored English suit. Paliov made a move to rise but the suit waved him down.

'Carry on--don't mind me.'

Dima recognised Timofayev, Secretary of Defence and Security, Paliov's political master. He lunged forward and took Dima's hand, a Tag Heuer watch sliding into view as his cuff moved back. Timofayev was one of the new breed of apparatchiks on whom Western accessories looked almost normal.

'So good of you to come. I hope we haven't taken you away from other assignments.'

'Only breakfast.'

Paliov winced but Timofayev laughed heartily, like a good politican, which caused Paliov's face to move unnaturally as he tried to form a smile in response.

'In fact, Secretary, Dima Mayakovsky is not currently on our--.'

'Ah, a freelance,' Timofayev cut in, pronouncing the English word without a trace of an accent. 'Are you familiar with that term?'

Dima replied in English.

'Yes, Secretary.'

'A man without allegiances, without loyalty. Would you say that describes you, Mayakovsky?'

'The former only,' said Dima, rather too pointedly for Paliov's comfort. He receded further into his seat. Timofayev looked Dima up and down.

'So, Paliov: tell me all about your freelance. Impress me with his credentials.'

Timofayev settled himself on the edge of the huge desk and folded his arms. Paliov took in a deep, wheezy breath.

'Born in Moscow, father a career soldier, mother the daughter of a French Communist Trades Unionist driven into exile by De Gaulle. Graduated first class from Suvarov military school, youngest of his year's Spetsnaz intake, which did not seem to hinder him from coming top in most subjects and disciplines. First posting Paris, where he perfected his English through contact with the American expatriate student community and infiltrated the French interior ministry with the help of a charming young--.'

Dima gave Paliov a look. He coughed. 'Subsequently transferred to Iran as instructor to the Revolutionary Guard.'

Timofayev roared with laughter, exposing expensive dental work. 'Promotion or punishment?'

Dima let his face go blank. 'Both: my station chief turned out to be working for the British. I executed him. You could say the posting was a reward for showing initiative.'

Timofayev hadn't finished laughing, but there was a cold gleam in his eye. 'Ah, don't you miss the old days?'

Paliov pressed on. 'After an undercover assignment in the Balkans he advanced to Afghanistan where he was responsible for developing a close rapport with Mujahideen warlords.'

Timofayev was still giggling, like a battery-operated toy that wouldn't switch off. 'All the choicest jobs. You must have made a real nuisance of yourself, Mayakovsky.'

A shudder from Paliov, followed by an exchange of looks between the two apparatchiks--then a silence which Dima didn't like the sound of. A silence while they remembered Solomon, the one who got away.

Dima wasn't going to rise to it. 'I accepted all assignments in the spirit in which they were given.'

'Like a true hero, I'm sure. And then? What excuse did they find to pension you off? Don't tell me. Too much initiative? Too "creative"? Or did they suddenly uncover some "unpatriotic tendencies"?'

Timofayev turned and glared at his Head of State Security, as if Dima's departure from Spetsnaz had been Paliov's doing. Paliov's round shoulders slumped further under the burden of his superior's disapproval.

'In fact, Secretary, Comrade Mayakovsky was awarded both the Order of Nevsky and the Order of Saint Andrew--.'

Timofayev cut in:'--"for exceptional services leading to the prosperity and glory of Russia", though probably not the prosperity of Comrade Mayakovsky, eh Dima?'

'I did all right.'

'But still a tall poppy nonetheless. My predecessors had a fatal tendency to be suspicious of excellence. Mediocrity was their watchword.' Timofayev swept his hand through the air.'Like Thrasybulus, who advised Periander to "Take off the tallest stalks, indicating thereby that it was necessary to do away with the most eminent citizens".'

He turned to Paliov, who looked blank.

'Aristotle,' said Dima.

But Timofayev was warming to his theme. 'You were too good, my dear Mayakovsky, and you paid for it. It's a credit to your patriotism that you didn't go West in search of better terms and conditions.'

He put his face close to Dima's. His breath was mint fresh with a hint of garlic. Dima's desire for breakfast evaporated.

'How would you like a real reward?' He squeezed Dima's shoulder, eyes blazing. 'You'll find our terms are much improved these days--entirely competitive with the best private security outfits. Your chance to get that Lexus, or the nice little hunting lodge you promised yourself. Somewhere comfortable and private to take the ladies: Jacuzzi, satellite porn, roaring log fire…'

Both of them looked at Dima who showed no reaction. Eventually Paliov gave a short cough.

'It may well be, Secretary, that Mayakovsky is not motivated by, er, remunerative compensation.' Timofayev nodded. 'Fine sentiments, rare in our brave new Russia.' He got up and paced over to Peter the Great, his handmade shoes squeaking very slightly.

'For a chance to serve, then.' He seemed to be addressing the woman in the golden dress. He wheeled round and fixed his gaze on Dima. 'Your chance not only to serve your country--but to save it.'

He had heard it all before; too many opportunities for glory…The words failed to have the desired effect. The suits could never believe it, but persuasion seldom worked with him. If anything it had the opposite effect. He had heard it all before; too many opportunities for glory and reward sold to him in the past had turned to shit. His stomach rumbled as if by way of response. Timofayev strode over to the window and jutted his chin at the view.

'Did you know that on the Khodinka field there, Rossinsky became the first Russian to fly an aeroplane?'

'In 1910.'

'And Tsar Nicholas the Second had his coronation there.'

'In 1886.'

He wheeled round. 'You see Dima, you can't help yourself. You are a Russian through and through.'

'Twelve hundred were killed in the stampede. They say their patriotic fervour got the better of them.'

Timofayev pretended he hadn't heard. He strode back over to Dima and put a hand on each arm of the chair. 'Come back to us for one last mission. We need a genuine patriot--one with your skills and experience, and commitment.' He glanced at Paliov. 'We could even--overlook the matter of the operatives this morning.'

Your country needs you to get your bollocks shot off, if you wouldn't mind.New furniture, new computer, same old threats. Your country needs you to get your bollocks shot off, if you wouldn't mind. Your choice naturally, though if you say no we have ways of making you change your mind. What the hell was he doing listening to this crap, when he could have been at Katarina's Kitchen, eating pancakes with Georgian cherry jam? Or better still, screwing the receptionist, whose fiery red hair framed a perfect white skin in a delicious vision of purity, with the promise of some very sluttish behaviour to come? Why not both? He'd done his bit, and deserved to enjoy himself for a couple of days--for good. Yet in some obscure part of his brain a small pulse of curiosity was beating.

Dima got to his feet and glanced at his watch, which still had a small smear of blood on the face, turning the '12' into a shape very slightly like a heart. He gestured at the frosted glass and the ghostly shapes of minions moving about in the outer office.

'You have a whole army out there. Young fit men and women jockeying for a chance at the big time, desperate to climb the career ladder. Whatever it is, the answer's no. You retired me. I'm staying that way. Besides, I'm hungry. Good day, gentlemen.'

He marched out.

For a few seconds neither of them moved. Then Paliov gave his master an 'I told you so' look and reached for the phone. Timofayev put his hand down on top of the old man's. 'Let him go. Forget about your casualties. But find something to make him agree.'

'He's immune.'

'Nobody's immune. There must be something. Find it. Today.'

Got a news tip or want to contact us directly? Email news@gamespot.com

Join the conversation