Redefining Games: How Academia Is Reshaping Games of the Future

College professors and other high profile scholars are paying more and more attention to video games. How is this attention affecting both the games industry and institutions of higher learning? This special feature explores that question and more.

Design by Collin Oguro

The history of electronic games, as relatively short as it may be, can already be divided into several distinct personalities. To the game developer, this body of history represents a list of successes and failures compounded by the belief that if only he or she would have had as much polygonal power in 1987 as exists today, the failures would be fewer. To the game-consuming public, the history is a dull lesson that drops off just short of the second-to-last game system actually owned. The future, to game players, is possibly more important than the past. To the collector, the electronic games history is a bible to be revered and a reference to be digested and divulged at classic game conventions. To the academic, this history is a disorganized, infantile beast--full of discrepancies and confusion--that's waiting to be collected, sorted, observed, tamed, and pushed into the realm of true innovation.

Each group, though driven by different motives, has something to offer the others. The game developer can teach the consumer what to expect in the coming months. The consumer can teach the academic about buying patterns and attention spans. The classics enthusiast can teach developers what makes a good game, regardless of era or trends. And academia can teach everyone a thing or two about what motivates a person to play games, why they are important, how we can make them better, and what we learn from them overall. Academia is also interested in collections, which benefits the developer, consumer, and classics enthusiasts fairly equally. Classic game fans archive too, but they usually do so for personal reasons and not for permanent public availability and accessibility. Furthermore, the academic archives less selectively, collecting all ideas, verbal history, written history, and digital history, which comprises a complete history quite unlike the conceptual history of electronic games currently available.

But there's a stigma attached to academia, particularly among game designers and game players. In a word, academia is "boring." GameSpot set out to challenge this notion by seeking some of the more compelling minds that are addressing game theory, which includes those who teach game studies and new media through universities, through thought-provoking games and Web sites, through art, and through community. The goal was to develop a State of the Union: Redefining Games: How Academia Is Reshaping Games of the Future. Because like it or not, electronic games are not babies anymore. They have been around long enough to stand on their own. So it's time for us to see what they're really made of so that we know what they'll become.

Planting the Seed

The 1970s were a big decade. Vietnam ended, Microsoft started, Skylab's crew returned to earth, home computers gave rise--and so did hip-hop--Pol Pot assailed the people of Cambodia, Patty Hearst got kidnapped, Margaret Thatcher took office, and Nixon resigned. It was a notable decade for electronic games too. By the mid-1970s, Pong and Atari were slowly gaining momentum, and the Magnavox Odyssey was turning TV sets into game stations. But the economy stunk, inflation was astronomical, and crime and unemployment were both rampant. Music wasn't much fun either. Video games' slow ascent through the septuagenarian decade laid the foundation upon which the $10 billion industry squats today, but the birthing ground was barren. A lot had to change over the course of 30 years to make games take root.

Russ Perry Jr. is the editor of 2600 Connection, an Atari 2600 newsletter, and he's a member of Cyberpunks Entertainment, which produced Stella at 20: An Atari 2600 Retrospective, a documentary about the original Atari programmers. He was only a preteen in the '70s, but he revisits the decade as an amateur historian. "A lot of people were starting to get the idea that making video games could be a pretty lucrative thing." Perry borrows a line from J. Michael Straczynski, of Babylon 5, by saying, "'The universe was holding its breath,' waiting for something to happen."

Plenty was happening. The Altair 8800 was the first PC to come to market, and the UPC symbol was introduced at grocery stores. The pocket calculator was born, and so went our ability to perform basic math without its assistance. The C programming language and Unix both emerged. Times were changing, but Perry says there were "plenty of people who hadn't heard of video games in 1974--and wouldn't care if they had."

Old-school Atari technical writer Bill Haslacher recollects that in the mid-1970s, PCs cost about $7,000, so massively multiplayer online RPGs (MMORPGs) were a long way off. But the first, true interactive computer game arrived in 1961--thanks to MIT student Steve Russell--and Haslacher remembers it well. "In 1974, Stanford's Tressidor Student Union sandwich shop had a time-warp peek at the future. It was Spacewar, and it was running on a Digital Equipment minicomputer lovingly crafted into a coin-operated video game." Haslacher says Spacewar was "never easy to play," but it drew crowds that were eager to toss quarters into its ad hoc coin slot.

If the smartest kids on the block could succumb to video games, how could the rest of us resist? The roots were already planted in academia.

Pinball had been around for years, but it hadn't significantly changed interactive entertainment. Arcades were seen, Perry says, as a "kind of lowbrow, 'bad influence' sort of thing" and not as a pastime destined for longevity.

Janet H. Murray, Ph.D. and professor and director of graduate studies in the School of Literature, Communication, and Culture at the Georgia Institute of Technology, has been instrumental in the development of Georgia Tech's new degree programs that will launch in the fall of 2004. One offers a doctoral degree in digital media, and the other offers a bachelor of science degree in computational media. Murray concurs that while pinball was considered somewhat of a low activity, "baseball is considered practically a religion," implying a social importance on gaming aside from the environment in which games exist. "If you consider the solemnity with which people--99.9 percent of them male--talk about baseball or football, there is no question that those are serious pursuits and that there's something very, very important at stake in the performance and the witnessing of those games." To Murray, sports like baseball and football are more appropriate antecedents to video games than the smoky pinball bar.

Murray explains that games are a representational medium, like television and film, so they must be considered in the same context. How well do they express themes and ideas? The pinball machine, Murray says, "really was very limited in expressiveness. Now board games, some of them were really beautiful and some of them were played with great attention and passion, but there's just no question that the digital medium adds so many layers of expressive possibilities to gaming." So begins the journey.

Jumping from Georgia Tech to Stanford University, meet Henry Lowood, Ph.D. and Curator for both the Stanford University Library's History of Science and Technology Collections and its Germanic Collections. Lowood also teaches a "History of Computer Game Design" course, which is in its fourth year at the university. Lowood's interest in games goes back about 25 years, beginning with historical and military board games, which were known as "simulations" at the time. "I've reviewed them in magazines for many years and have been involved in their design," says Lowood. "This was also the basis for my jumping to doing design on computer games about five or six years ago with a [Stanford] colleague, Tim Lenoir, who's a historian of science." Lenoir, also involved in researching the history of the military through simulations such as SIMNET (SIMulator NETworking), and Lowood formed the Stanford Humanities Laboratory project "How They Got Game: The History and Culture of Interactive Simulations and Video Games." The goal of this project is to "explore the history and cultural impact of a crucial segment of new media: interactive simulations and video games."

To determine the future, one has to determine the past, and Lowood, his colleagues, and students are dedicated to the task. But to study the past, they need artifacts--man-made items that tell a story about the way things were. In the history of electronic games, there's a particularly sticky issue at hand: One artifact begets another. To play software, you need hardware--and it's not always readily available or functional. "It's a huge problem, and it's a huge mess," says Lowood. "It's even a mess for the straight, linear media in the digital realm, like online journals and magazines. That's already a mess, but it's a relatively simple problem, relative to interactive medium on all kinds of weird platforms, some of which are computers and some of which are weird things that connect to televisions and so on."

One obvious solution in the race to preserve games' past is emulation and people working in emulation around the world--who also share Lowood's goals of archiving the playable history of interactive games and support his efforts. "What we've done at Stanford is mostly collect artifacts [of] packaged software and hardware, [in addition to] collecting papers from people who have been involved in the industry (which is another important thing: we won't know anything about development if all we have are the packaged games). And [we've been] collecting the performance part--the game-playing part of it," says Lowood.

Like chasing smoke to find the flame, emulation creates its own set of problems. For one, Lowood says, "emulations don't reflect what the true experience was like playing an MMORPG or playing within a game society in a live experience." He likens this to playing a copy of Everquest 50 years from now, provided it runs. "It's not going to mean much, because it's a game that was dependent on a community of players. We have to give a lot of thought to how we're going to preserve what happens in these virtual worlds and multiplayer games and any kind of game, because those will be the artifacts that document the experiences people had."

Lowood is not discouraged, though, because on the uptick, unlike with film--wherein much of the early history was never archived--electronic games are relatively new. So if now begins the process, so begins the hope.

Fast-Forward

Thirty years after games were widely introduced to the public, electronic games are now "fully entrenched in popular culture," Perry says. Games today have recognizable brands, such as Mario and Metal Gear Solid, with franchises such as Madden Football returning with the regularity of a birthday. These are big, successful games. They are also generally thought to be good games. But do we think about games any differently today than we did three decades ago?

Georgia Tech has an Experimental Games Laboratory, which Michael Mateas, Ph.D., of the School of Literature, Communication, and Culture and of the College of Computing, runs. Mateas' focus is artificial intelligence-based art and entertainment, melding research with art, thus creating what he calls "expressive AI." Mateas' research reaches back through the annals of game history to determine where games might be headed, specifically related to AI.

"A lot of what I'm really interested in is genre innovation, so I'm trying to create experiences that aren't clearly action adventure, RPG (role-playing game), RTS (real-time strategy), FPS (first-person shooter), or any of these fairly well-defined marketing categories for commercial games." Mateas defines experimental games as "radical genre innovation that requires both design and technical innovation."

One theory, at least among gamers, is that true innovation is thwarted by developers' needs to build games that fit within the ordained genres for sales purposes. Murray thinks that new genres are forming, however. "I think it's very telling to me in Eric Zimmerman and Katie Salen's new book, The Rules of Play, where they come close to excluding Sim City as a game, because it doesn't have a winning condition," says Murray, suggesting that by the same standard, The Sims might also be excluded. "If you're going to exclude one of the most popular games of all time...then it's because 'game' is too narrow a word. And I think that we'll start to think about games the same way we think about movies--as a sort of metacategory where there are a lot of different categories. I think there are things that are emerging that are new forms, and it challenges the boundaries of what we're used to thinking of as games."

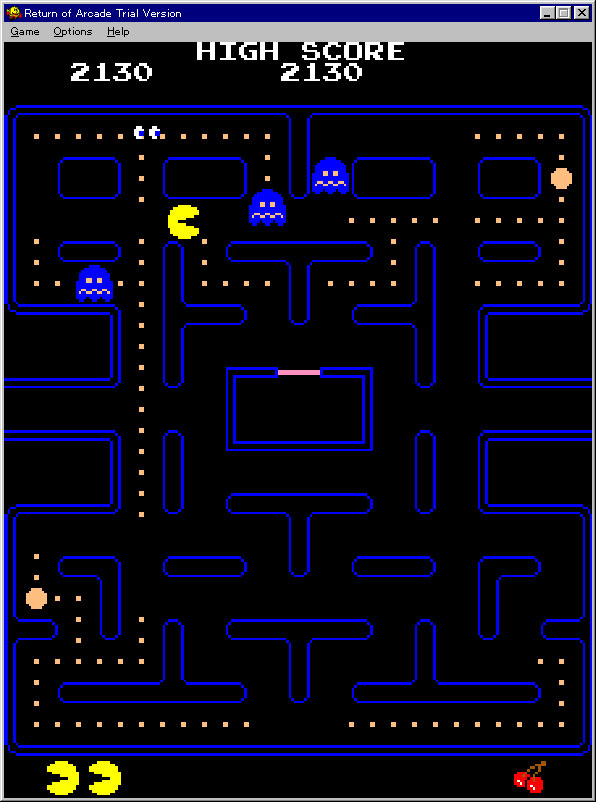

"AI" is another term that gamers and those interested in selling games throw around loosely, as compared to academic definitions of the term. "I do believe in a sort of consistent idea underneath the term AI," says Mateas, "which is this idea of a psychological project. What [marketers] mean is smarter enemies--maybe characters that you can find more engaging. Many of the techniques that are used in games that are called AI aren't really recognized by academics as being AI," Mateas explains. "I still think it's fair to say the game AI drives the part of the experience that you, as a player, can sort of project an inner life onto," as opposed to physics, which is commonly mistaken for AI. Psychological projections, according to Mateas, are indicative of true AI. Does your character have goals? Is another character doing something to you? Is a non-player character (NPC) mad at you? Assuming that AI is the child of more-advanced technology is a misnomer, because AI is not necessarily reliant upon complex lines of code. "You could have a really beautiful and complicated water effect in a game, with really nice ripples and shading effects, and, of course, there's some complicated stuff under the hood to make that happen," Mateas says. "But the player, when he or she is experiencing that water, doesn't have to project any internal state onto it. Whereas with the ghosts in Pac-Man, where the code is much simpler than the water effect, you do project a state onto them."

How can we learn from this to make deeper game experiences in the future? Mateas believes, coming from an AI background, that some of the more complex techniques from academic AI can now be "reexamined, reexplored, changed, and used to achieve even richer psychological projections." The future of games might be less about stunning physics and more about meaningful character experiences, or perhaps a balance of both. In this sense, The Sims can tout more AI than a first-person shooter, wherein enemies know when to approach you and when to retreat. "At the end of the day, trying to create this illusion of sort of a living world is really what AI is about," says Mateas.

What Defines a Game Anyway?

It isn't possible to determine the future of games if the word "game" has not been properly defined. An easy response to the question, "What is a game?", would be, "What are you, crazy?" Games are so commonplace and recognizable within society that the term itself defies definition. "Games" can be board games, political games, video games, mind games, ball games, or betting games. From the viewpoint of academia, the definition of "game" is too important to blithely breeze over. To the rest of us, it wouldn't hurt to listen.

The question "What is a game?" is a great one, states Murray, who says the answer is complicated--not a one-liner. "Games are a contested source. It definitely has something to do with rules, and it has to do with the magic circle--being in a world that is self-contained and without consequences in the real world." Murray continues that games have to do with a social contract and that you can't have a game unless people agree about the rules. "Even if you're playing by yourself, the rules have to be externalized in some way. They represent some synchronization of your behavior with standards that are held by a larger community," she explains.

Even solitaire? "Yes. Exactly. What is it if you're cheating at a game of solitaire? It's a meaningful transgression," Murray points out.

The book The Rules of Play did not consider Sim City and The Sims to be "games," since they lack a specific win or lose function. This definition describes games as experiences that rely strictly on end results and goals rather than process. The process--our journey through The Sims, for example--is gamelike, but it's not a game; it's this standard. "But I think it is a new kind of game," Murray says, "because it's a simulated world, and there are also simulated worlds that are less gamelike. Because there's more at stake, the thing represented is less playful, less funny. I think these are just all new artifacts in the world, and we have more artifacts than we have categories [genres]."

Game designers of the '70s and earlier had the "heroic task," according to Murray, "of making the medium as well as making the individual games." Designers today, she says, get to work in the tradition of the early developers, but they also adopt the task of extending the medium by refining the genres. To Murray, one of the most interesting tasks now is coming up with the words that describe what makes a good game. She added, "And what are the goals of gaming, and how do you distinguish one feature from another?"

The language of games today falls into two categories, Murray says: fan language and commercial (or "naïve") language, such as the manner in which people talked about television 30 years ago and film in the 1950s. "But there's now getting to be an academic and an educated reader's discourse about games. It's interesting that game designers tend to be quite articulate, so they're generating that themselves." Murray credits game designers' roles in this lexicon as helping the academic disciplines "because it prevents them from becoming too arcane," she says.

"I think people want a critical vocabulary for games. I think that academics are always looking for cultural forms onto which to apply their philosophical and critical discourse. But I think that people who make games and who play games are actively searching for a critical vocabulary to compare games and to look for identifiable features of games," Murray says. "People care passionately about why a game was disappointing or thrilling, and they want to be able to articulate that."

Mateas' is searching for definition in games, too, although his method appears more cryptic on the surface--since he's looking for language in design. Mateas oversees a Georgia Tech research venture called the Game Ontology Project (formerly the Games Morphology Project, run by Murray) . Whereas the project used to be about looking for patterns in games, with the aim of defining existing genres (in terms of design commonalities, not actual marketing genres such as RPG, action, etc.), the new focus is on enumerating all the pieces of game design. Mateas emphasizes the importance of developing relationships between design elements found in games to determine, for example, how a design feature in one part of a game ripples throughout in other areas or levels. "Design decisions are never made in a vacuum," Mateas states. "They are tightly intertwined in each other, and it took us a while to, as a group, figure out what we wanted out of the design language." Back to the defining board, Mateas says that a design language is something that people in commercial game development and academia have been talking and writing about for a number of years. "Even I have been trying to figure out what that means. For me," Mateas notes, "it means trying to define the relationship between design decisions I make and how they influence each other."

A Serious Narrative Form?

A video game would not be a video game without visuals and design. But arguably it wouldn't be much fun without a point--or something to do--whether it be a story, a goal, or at least an environment to walk around in. There's a great deal of discussion in game theory academic circles about the importance of story and narrative in games. In the summer 2004 issue of The Paris Review literary magazine, the renowned Japanese author Haruki Murakami, in an interview, says, "I think video games are closer to fiction than anything else these days." The interviewer responds, "Video games?" with transparent surprise and bewilderment. Murakami then explains that he doesn’t play video games, but feels the similarity. "Sometimes while I'm writing I feel I'm the designer of a video game, and at the same time a player. I made up the program, and now I'm in the middle of it; the left hand doesn't know what the right hand is doing. It's a kind of detachment. A feeling of a split." Murakami is a traditional pen and paper writer. He works at his kitchen table and is not, as his fans know, in any way part of the so-called digital revolution. His awareness of the role of narrative in video games is instinctual, not studied. Murakami's comment may be interpreted as a sign that video games are becoming more influential than we possibly know. But does story affect technology, or does the technology affect the story?

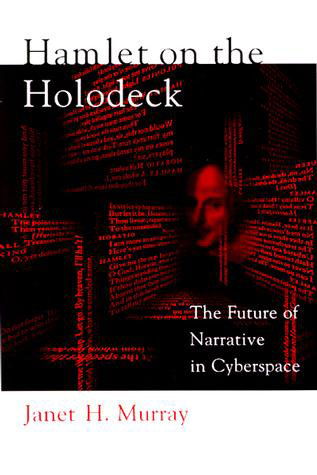

In 1998, the MIT Press published Murray's book Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace, which argues that technology affects the way stories are told. Games--like comic books and, at one point, television, radio, and the Internet--have suffered from the awkward transition from one medium to the next as new vehicles for our stories emerge. Naturally, all forms can and do coexist, but some are more widely accepted than others.

To Murray, dismissing games as well as comics because they are enjoyed by and are accessible to a broad, relatively mainstream audience is a narrow viewpoint. "I think comic books and games are similar in that they have a strong popular face. They are an accessible mass cultural form, and they also afford an enormous range of expressions," she says, adding that games, like comics, have artistic tradition as well as entertainment tradition. "I think all strong expressive traditions grow out of wide practice."

People have learned to take the games industry, if not games themselves, somewhat more seriously thanks to the business's well-publicized, multibillion dollar annual sales figures. But the public seems farther away from appreciating games as a credible source of stories, although it could happen. Murray says the interactive nature of games adds dimension to stories. "I think it's as if we knew how to make paintings, and now we make sculptures. We now have a way of telling stories procedurally, so now we can tell stories that aren't unisequential (those that don't have one sequence to them) but are multisequential. And, also, we can tell stories that are multiform--that the same story elements can be combined in different ways." Murray calls this method native to the human mind but adds that we haven't had a medium to reflect this way of thinking before.

Before digital entertainment, efforts had been made to make text more dimensional. In the 1970s, R.A. Montgomery and Edward Packard published a series of books called Choose Your Own Adventure. These young-audience books were specifically designed to let the reader control how the story should progress. At the end of each page, the reader was given two or more choices that would propel the story's action forward. He or she then turned to the page that corresponded to whatever choice was made, and the story continued. While they may be remembered fondly for the nostalgia factor, Mateas says these books were basically a failure because of the way the stories were built--on a branching structure of finite choices. "One of my strong beliefs in thinking about the future of interactive story," says Mateas, "is that no technique based on a graph, where you can essentially draw out all the possible paths (and, of course, Choose Your Own Adventure is an example of this), no method like that will move us to the future of interactive fiction or interactive narrative." This would present a proverbial dead end, it seems.

Finite choices in finite numbers of rooms or environments with finite numbers of weapons or enemies are basic tenets of commercial game design today. But certain trends in games show that designers are beginning to break out of that box. Albeit the best efforts, such as Grand Theft Auto, still have a long way to go from scripted choice points--even though players are pretty much offered a free range of movement. The flip side, Mateas says, is that when you play around in a huge, open world like GTA, there is no story structure. "So you just sort of wander aimlessly and crash cars aimlessly--to the extent where they did put story structure into the game in that you can choose to do the missions. If you do the missions, you're back in this sort of tightly scripted situation," Mateas argues. Peter Molyneux's Black & White is a similar example. The player is offered freedom of movement, but to make things happen in the game, structure is reintroduced--and then along come the scripted decisions again.

"There's this tension to create these big, open spaces where the player can do whatever he wants," Mateas suggests, "but nothing happens over time. You wander and wander and wander and wander, and five hours later, you're still watching, but nothing's progressed. And the only way that game designers, as a community, know how to do progression is to basically enforce it with these quasi-linear scripts. We have to get out of that box and create something that has progression but that still has a lot of the openness of open-ended worlds. That's the focus of games like Façade and some of the games in the Experimental Games Lab. That's one of my big priority items to work on--to try to figure out how to do that."

Don't expect to find the Experimental Games Lab's interactive drama Façade at the local Electronics Boutique anytime soon, but to Mateas, components that make up a good novel, such as rich characters and a rich story, are signs of an intelligent game. And Façade is one of his serious efforts to this end. "I think that achieving this kind of drama is going to require fundamental advances in AI technology," Mateas says. He, along with Andrew Stern, has been working on the Façade project. In Façade, the player acts as a third party at a get-together over drinks with a married couple. The player becomes involved in the couple's marital troubles as the plot unfurls. But the game is not all story-based. Mateas reports that Façade actively includes some aspects of gameplay that are traditionally associated with real-time games. As a result, you can move around, it's 3D, and you can do whatever you want when you want. "We were trying to bring in real-time, simulation-world aspects of games and combine that with interactive story and characters," Mateas says. "I think if experiences like Façade are successful--if they work as player experiences--the game industry would happily, sort of, heap them up under the umbrella of gaming."

Although Façade may not sound like a traditional game by today's standards, especially when run through classic definitions of "game," Mateas says 15 years ago, if The Sims was to have been described to game designers as a hypothetical design, they might have said that it wasn't a game either. Mateas finds the term "game" bendable and is optimistic that the definition is expanding. "We took Façade to the Independent Game Developer's Conference last year, and so, right there, the term game seems to be OK to apply to Façade. I think 'game' will turn into a very large umbrella term, and you'll have to refer to more-specific things under it. So things like Façade may be referred to as interactive dramas or something. And I think 'game' will come to mean, sort of roughly, something more specific than 'interactive experience,'" Mateas explains.

Mateas creates another narrative with his games-and-new-media blog called Grandtextauto.org. He and four others, including Stern from Façade, wanted to create a blog modeled after a conference panel, where people talk among themselves about a specific theme and then invite the audience to comment and elaborate on the ideas discussed. A search-based "drama manager" is another of the Experimental Games Lab's projects. While only a technical name, the drama manager technology is an AI component that will work above or beside an open-ended gameworld, intervening to make longer-term story structure, not branching structures, happen.

"Drama manager has a model in its head of what this open-ended world will look like," Mateas explains, "and [it] makes decisions based on that, such as 'Let's remove this object from behind Clare's back,' or 'Let's give this NPC a goal to talk or to run away from the player,' so it's constantly intervening in ways that guide the experience toward interesting narrative directions but not in a sort of scripting or branching way."

But will the average gamer have any interest in playing games with boundless freedom? Aren't well-defined goals actually a plus for some players? "In part, I work on experiences that I would like to play [laughs]. I think a lot of designers do, actually," Mateas agrees that "the jury is out on whether there's a big section of the population that would like to play these games."

At IGDC, an attendee approached Mateas, who was playing Façade, and asked, "What is this?" Mateas refers to the comment as "great." "It just doesn't look like any existing genres," he defends. "Gamers have been trained on what the sort of permissible genres are. And games that do genre-blending, when innovation happens, [end up producing] games like The Sims, which really just sort of '[from] out of nowhere' create these new genres. And that's relatively rare."

Regardless of the best efforts of The Sims, Façade, and other story-driven, free-roaming "games," many people still associate games with pure amusement that, Mateas says, is prone to acceptance by audiences of children and early teens. "I think there's a sort of hangover of '80s arcade culture on the games scene or in some people's minds. And people like the Serious Games Initiative folks feel they have to fight against it in some way. I grew up in '80s arcade culture, so I loved it. I think, in some, the stereotypes of that culture are what people feel the need to sort of defend themselves against when they talk about 'serious' games."

Ludologists Unite

There are two schools of thought on the subject of narratives in games--ludology and narratology. The narratologists believe that games should have more narrative, and the ludologists say pure simulation, sans narrative, is the way to go, explains Mateas. He believes games can or should be both.

Game researcher and developer Gonzalo Frasca thinks that's an oversimplification. He works at the Center for Computer Games Research at the IT University of Copenhagen and represents a strong ludologist presence online. He has published a seminal game theory site, Ludology.org, for the past four years and is a cofounder and senior producer at Powerful Robot Games.

"Some argue that ludology only cares about abstract game mechanics and disdains narrative content," Frasca argues. "Of course, it doesn't make any sense. If I only cared about abstract mechanics, I wouldn't be making political games! Nothing is more concrete than politics!" Frasca credits the popularity of the belief that ludology favors simulation, while narratology favors narrative to the simplicity of the argument. "People like simple ideas," he says. "When I proposed the term 'ludology' in 1999, it was as a reaction against researchers who wanted simply to fit tools designed for film and literature into games. We all know how disastrous 'interactive film' has been. Ludology simply argues that we first must try to understand games as games. It is not the easiest path to take, and it goes against the established theories of narrative, so that's maybe why we are taking so many attacks from conservatives," Frasca says.

Frasca suggests that players do not play games for the storytelling. "They are drawn because these games allow them to live an alternative life." He believes simulation allows players to safely experiment within environments that are "dangerous or impossible to access (Black Mesa, Vice City, Yoshi's Island, for example)." Narrative, he says, "is about what has happened. Stories are objects that are trapped within a book or a DVD. Games are about what could happen, about what-if scenarios, about experimentation."

The Web site Ludology.org attempts to make sense out of video game culture not by scrutinizing the industry buzz through sales performance figures but by examining the phenomenon from an academic or, daresay, critical viewpoint. Frasca believes games have come of age throughout the last 30 years and that finally, after decades of "harmless fantasy and sci-fi characters," game developers have discovered humans are fun characters to play as too. "We are leaving behind orcs and trolls while exploring the human condition in the suburbs (The Sims), within the couple (Singles), and even in the underworld (Grand Theft Auto 3)." Perhaps the ludologists and narratologists can agree on The Sims after all.

Frasca started Ludology.org because he was tired of looking for a resource for people interested in researching games. "Since I couldn't find one, I started my own. During the last three years, there has been an explosion of interest in game studies, and I guess the site fulfilled a need for this growing community." Frasca hopes that the growth continues and spawns multiple resources and publications. Why? "So there will be no more need for Ludology.org (and therefore I can focus more on making games and doing research)."

While Frasca's earned his share of academic credentials, he exercises a practical approach to game criticism and theory. In his own game-review writing for Game Studies, he understands that an academic tone can "put readers off." "I have really worked hard to make the [reviews] accessible not only to academics but [also to] gamers in general... Personally, I think academics need to work harder to reach a wider audience, but, on the other hand, it is true that certain subjects need a more precise technical vocabulary that may not translate well to the general public."

The general public has no shortage of game theory, discussion, and actual gameplay Web sites at its collective fingertips. Notable sites include Frasca's other projects,WaterCoolerGames.org and Newsgaming.com (discussed later in this feature), and Gamegirladvance.com, erasmatazz.com/Library.html, terranova.blogs.com, memorycard.blogs.com, quantumphilosophy.net, seriousgames.org, and games.slashdot.org--just to name a limited few. As with any Net community, one discovery leads to another, so the best way to find them is to pick a starting point.

Frasca says anybody who has spent just a few minutes wondering why one game is better than another has the kind of curiosity that drives ludology. "A ludologist is somebody who wants to have a better understanding of games," he says. "So I think that everybody, hardcore or casual gamer, is a ludologist at heart."

Gamers Wearing Tweed?

Setting the ludologists and the narratologists aside, there's another division in the games community that can be drawn against academic and professional lines--those who go to school to learn how to make games and those who go to school to learn about games, which is called game theory. Mateas notes that all too often the camps do not see eye to eye. "I think some of the best academic games studies happen when you're engaged in design, and you're doing this sort of theoretical analysis that allows you to sort of step back [to] take stock [to] try out your theories in design and [to try to] step back [to] take stock and try them out again, and so forth," says Mateas. The alternative, he says, is for game studies to go the way of film studies. Mateas sees "almost no relationship anymore between film studies and people who make films. They're like two independent communities that never talk to each other. They only talk to each other through their artifacts. One makes artifacts, [while] the other analyzes." Mateas says the situation is a shame, because the best designers are theoretically informed designers. "I sort of sense this split starting to emerge, and I hope that doesn't go too far," he says.

Mateas' students have "very strong rounding in commercial games," he notes, "but they've also been very interested in interactive story. And that's been a place that's been sort of a natural for radical innovation, because we don't really have truly interactive stories in the game world yet."

Georgia Tech's New Media master's program includes 40 students, and the school's doctoral program includes five, with as many as 20 to 40 percent of them at any given time focusing on games. The master's program was established in 1993, and the doctoral program will begin this year. To Murray, the growing interest in game studies can be attributed to a few different factors. "I think, frankly, that The Sims was an enormous breakthrough, and it proved that you could have a wildly popular game that has a very down to earth, everyday narrative to it. And it engaged a wide range of players--more women than men," she notes of the breakthrough game. She adds that the growth of multiplayer online games is creating a "new culture around gaming" and that interactive television is joining that circle. "In Great Britain, for example, a large portion of the television audience is playing online quizzes and online gambling all because they have an interactive button right on the TV remote," she says. Widely available and highly accessible Web-based games are a factor too, Murray says. All of these things are building what she calls "critical mass" on the availability and range of games. Murray sees games as an "age-old" cultural form and finds it more surprising that we haven't studied them in any depth before.

Lowood, who doesn't believe that academia has had much of an effect on games yet, refers to the tension between the game development community and the academic community as a "pet peeve." "You have the practical game design community, and you would have scholars working on game studies. And, very often for a more scholarly type, to gain credibility in the game design community, [he or she has] to do something that's more akin to designing a game," he says. "It may be an issue that games designers may or may not be interested in what you, as an academic, write. But that doesn't mean that the work that the academic does is not worthwhile." Lowood is not someone who writes about games from a detached viewpoint from the industry frame of reference. He is in contact with many game developers in his work. "I haven't really designed much in the way of games, but I have been involved, in the way of support, [in] both computer and noncomputer games. So I kind of know what they do."

Lowood believes many game designers have a narrow view of what academia contributes to game development. "Game designers will say, 'Well, we're really not that interested in what academia has to say about that game. We're more interested in just talking to people when we have a problem that we need to solve, an algorithm in computer science, or a psychological point--or [when] we need an economics model and [need help] finding an expert that can do that for us,'" he says. "'But we're not really interested in reading the literature on games, because those guys haven't designed games.'"

"It's a pretty tenuous relationship right now," Lowood says. "In some ways, I think the player community seems more responsive to the interest of academia than game designers. Perhaps it's the player community that is seeking an education in game studies. Students who are drawn to Lowood's class are looking for an outlet for critical discussions of games, which they grew up with, he says. One student is working on an honors thesis in controllers, while another is working on nontextural ways of telling stories. Yet another student is working on dancing games, while one is working on a history of first-person shooters. All represent very distinct themes.

"When you get somebody who's this specialized already and this motivated to study their specialized area," Lowood says, "you're basically just facilitating what they do. They already have a really strong notion of what a game is and what's interesting about games."

It's difficult to determine what exactly is luring students to the quickly emerging "New Media and Game Design and Theory" courses that are cropping up at universities and colleges around the United States and all over the world. On one hand, game development has become a high-profile, lucrative, entertainment-based profession. A good career could be the drive. On the other hand, games play such a critical role in pop culture, naturally people are curious and want to learn about them and possibly teach others. Still, others might be interested in making games of the future better, even if they don't have the skills to make games today. People are engaged in game culture, and beyond the numerous Web sites dedicated to game discourse and theory, books are beginning to slowly emerge on the subject to reflect this interest, even though they are still somewhat far from the mainstream.

"There is this collection of books," Frasca notes, "called Ludologica, edited in Italy by Matteo Bittanti. Each book is a 100-page essay on a single game, paying special attention to the game designer(s)." Frasca says the books are now available in major game shops, even though they are far from being best sellers so far. Frasca chalks this up to the fact that many gamers are "truly interested in learning more about their hobby and going deeper into its understanding. It is important that gamers get more sources of serious game criticism." So far, the Web, he says, has played a great role in this sense, "but there is still a lack of an equivalent of a publication that does what Rolling Stone magazine did to music--not just reviews but also writing more about a certain lifestyle."

Lowood supports the idea that people should start seeking books that treat games in a more sophisticated way. "I don't mean academic books, by the way--[and] strictly speaking--but books that a general audience can read that [will] maybe benefit, to some degree, [from] academic studies," he says.

Frasca recognizes that many gamers are looking for instant gratification from game publications. What's out, and how good is it? And if it is good, what are tips for playing it? "Ludology.org does not offer game tips or walk-throughs, so what is published there has no immediate use for the average gamer. My main goal is to make people think about the important role that games play in our lives. [We need] to think more about what games are, what they have been, and what they could be. It may sound like a waste of time to a bunch of people, because it may not provide recipes to make better games. But research is about long-term goals, not immediate results," he says.

This perspective has academic undertones, but Frasca, who is responsible for creating the Dean for Iowa online political campaign game as well as the notable September 12th and Madrid games, insists that he is "not your average academic," because he's not satisfied simply writing theory about games. "I also worked many years as head of production of Cartoon Network Latin America, and after that, I lead a team of a dozen people at Powerful Robot Games studio. Personally, I think that there are some things that you can write about, but [there are] other things that have to be explained through action. That is why, in addition to writing about political games, I also launched Newsgaming.com in order to put my money where my mouth is. I do think that the Howard Dean game, which I codesigned with Ian Bogost, would have been quite different if I hadn't spent a couple of years thinking on issues of political-game design." Frasca says that while working on his thesis at Georgia Tech, lots of people thought that he was crazy. "A professor in my committee asked me: 'Do you seriously think that games can change the world?' I still have the same answer: 'Why not?'"

For games to change the world, a combination of technical know-how, creativity, and critical understanding of games as a medium and gamers as an audience is necessary. A game that changes the world may not spring solely from theory, but most likely it won't come directly from the marketing department either.

Still, Frasca, all practical notions aside, agrees on the importance of developing more game research departments, such as Stanford's and Georgia Tech's, in other universities. "Many gamers may think that university professors studying games should get a life, but I have a challenge for these players: Wouldn't it have been much nicer if you spent hours in college discussing Zelda rather than a boringly long story about ancient Greeks? Would it be great to spend hours in school dealing with an art form that truly speaks to you, such as games, and less about paintings or sculptures that are hundreds of years old?" Frasca considers the importance of studying the classics but asserts that today, "Will Wright and Miyamoto have more cultural influence than Shakespeare and Homer, because they are alive and well, and because they speak to us."

"Academics are working hard so people can take games more seriously, and so they become part of the education curriculum," Frasca notes. "Education does not have to be boring. It is perfectly OK to understand the world through interesting and entertaining objects, such as video games. Of course, they should not simply replace other media, but it is essential that they are given a more important [place] in our classrooms."

Game studies programs lure gamers and nongamers alike, but so do community games, either multiplayer party games or online games. Game courses at universities also emphasize a social element--which includes discussing and learning about games in a group--and these students are changing the meaning of "serious" gamer. "It is funny, because other media do not colloquially divide their audiences into hardcore [and] casual [participants]," Frasca points out. "Are you a hardcore poetry reader? Or a casual sculpture appreciator? Most people do not think about how they are towards a medium. They simply know what they like and what they don't like. People appreciate quality in any form. Some people just play chess and love the game, even though they may not recognize themselves as gamers. It's all about finding the game or the games that are right for you. The problem is that the industry mentality is that people should become consumers and buy a new game every month. Imagine trying to convince [Gary] Kasparov that he should quit chess and try a different game every month. I could easily just play Age of Empires for the next few years without having to buy any other video game." Kasparov was not just playing chess; he was developing theories, which, in turn, made him better at chess.

"A lot of English and humanities departments thought that the dot-com craze was going to provide them with a safe environment for teaching new media," said Frasca, "but suddenly, the dot-com bubble burst, and now the really relevant new media product that is actually generating big revenues is game production." Frasca admits that older faculty and university administrators still have a tough time taking games seriously but says the reality is that "These people are quite old, and, unlike Mario, they do not have multiple lives. So after they are buried and long forgotten, new generations with more-open minds will take over, and students will be able to major in video games in the same way that they now major in literature or film studies." Thirty years ago, the thought of receiving a doctorate in game studies would have been but a mere fantasy.

Simulation vs. Reality

Games as a credible course of study within universities is a reality. While this reality continues to emerge, issues that have plagued the games industry for decades will float to the surface and earn prominent placement on syllabi. The students have their work cut out for them. The simulation versus reality argument is possibly the digital entertainment realm's mind/body dualism issue. When we act through our character in The Sims, for example, at the moment we are playing, do we become the character, or are we simply acting the character? The ghosts in Pac-Man may have allowed us to reflect upon an internal state, but who felt they "became" the ghosts? Games today, especially MMORPGs and products like Black & White and The Sims, hijack our personalities, at least temporarily, while we escape to an alternate, but not always better, world.

Role-playing is ages old, but it is a particularly powerful force in early 21st century gaming. Frasca concurs that games are moving away from fantasy and toward reality and says, "As soon as you start playing with humans, things get messy and political--and therefore far more interesting. Thirty years ago, I could pretend to be a spaceship. Now I can be a housewife in The Sims. Without an inch of sarcasm, that's what I call progress."

Conceptual artist, writer, and musician Paul D. Miller (aka DJ Spooky - That Subliminal Kid) wrote in his recent book, Rhythm Science (MIT Press, March 2004), "Today we have an entire youth culture based on the premise of replication, which itself derives from the word 'reply.'" Replication of the self through refraction of our surroundings, as he describes, is most obvious in RPGs and simulations. Miller told GameSpot that he sees video games today as a "shorthand method" for grasping realities more complex than people are trained to understand. "Video games let people deal with a lot of information in a small amount of space" before moving on to the next level. The hope of "always evolving and attaining the next level," Miller says, is based on "much more rhetoric about reality than about reality itself."

We've come a long way from the days of minimalist characters sparring in an overly simplistic world where the "good guys" are differentiated from the "bad guys" by color and shape. Naturally, games have adopted the same complexities as life.

Games today, as opposed to those created even 15 years ago, are "more real than real," Miller says, "but there's also more distance between yourself and reality than anything ever before." Miller sees a greater amount of alienation in games and in the media in general, which leads people to "cling to whatever it is that they consider real," when the fact of the matter is, what they identify with as "real" is "just a TV show."

The effects games have on society, however, are real. In April 2004, a Beth Israel Medical Center study revealed that "Doctors who spent at least three hours per week playing video games made about 37 percent fewer mistakes in laparoscopic surgery" and were 27 percent faster than doctors who didn't play video games. While debates over video game-inspired youth violence are pandemic, studies have shown that games can be good for you. They can improve reaction time and hand-eye coordination.

Miller calls games a "good training mechanism" for living in the information age. "I think it's all about responding to a digital environment in a way that you improvise and, at the same time, react to [with all of this] information around you." We can learn from games, he says, but they will "absorb more of our psychology."

For the type of simulation games that Lowood focuses on, which are primarily military sims, the question of "Why reality?" is clearer. "It's basically because [sims/realistic games] are a really good way to teach people or to train people how to do something, and that's a very practical kind of objective, and it doesn't hurt at all for something like that (in fact, it's a benefit)--that games can be very compelling for people." Lowood admits that he finds The Sims, as a gameplay experience, a little puzzling in that it's not like true simulations in that a player does not necessarily learn from it. "I think, probably, the connection to the real world in those games, and I'm relying a little bit on what I've heard Will Wright say about it, is not so much that the person playing really identifies with that character but more that the fascination is with the little variables--the little changes [a player] can make and the repercussions that those little changes have as behaviors emerge out of that character."

Frasca says players are "hungry for games that talk to them in a more realistic way, dealing with subjects different than fantasy and science fiction." The Sims, he says, is a clear example of this. "And we have to keep working in this direction if we want games to help us to better understand our world."

Newsgaming.com is one of Frasca's efforts in this direction. He and his development studio, Powerful Robot Games, spend three months per year working on independent projects that are not aimed at profit. Newsgaming.com is a product of this model, which allows them to make money in commercial interests for nine months so that they can then fund independent projects. Newsgaming.com features short, politically or socially driven games that are a strong combination of message and ease in playability, thus making the games accessible to all so that their messages get across. The well-publicized September 12th, a game in which players must "bomb the terrorists" that are hiding out in a generic Middle Eastern village while attempting to avoid the civilians (an impossible task, by the way), is less of an actual game with objectives and more of a dialogue on reactionary politics, such as the US retaliation for the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001. Frasca calls the game, which took him three months to produce and that finally launched in October 2003, "simple" yet "powerful in its message." To date, hundreds of thousands of people have played the game, according to Frasca. "From the beginning, I aimed at the game to be played just for a few minutes. I was not aiming at replayability but, rather, at modeling--in the same simple way that cartoons work--some aspects of the war on terror," Frasca says. Some people accused the game of being anti-American, but Frasca contests that, sadly, the disastrous events in Iraq, over the course of a few months after the games launch, "gave more validity to the points that the game was making," he says. "As the body bags kept returning from Iraq, it seems as if the game message started to make more sense. The visitor stats kept quite stable, but the amount of hate mail decreased over time. Even the media coverage became more enthusiastic." September 12th started with an "interesting" from the Wall Street Journal in November 2003, which became a "fantastic site" from USA Today by July 2004.

Frasca's goal with the game was not to sway people toward his political views but rather to generate debate, he says. "Every week I check for the referral links, and I find the game being debated on gamers' online forums. If a little game can encourage young people to discuss international politics, then my mission has been accomplished. I couldn't be happier." Frasca admits the game has been accused of being "one-sided" for only showing the "terrorist" side, but he maintains that had he shown a more "balanced, politically correct game, everybody would have agreed with it, and no debate would have emerged. And debating is a good exercise for the brain, you know?"

Another example is Madrid, a somber game in which players must keep candles at a vigil alight to commemorate the bombing of the Madrid rail system in March 2004. Frasca created Madrid in a couple of days to "explore the emotional side of terror" in the form of an homage to the victims. "It was quite a difficult idea to work with. How do you turn terror into a game? I know most of the people were scared when I told them that I made a game about the attacks in Madrid, because they assumed that games would trivialize the lives of the dead. The game mechanics are Wack-a-Mole, but the message wants to be one of hope--that we can, all together, stand up against injustice." Frasca says he didn't receive hate mail for Madrid, but among the e-mails, "There was one from this man who told me that it was the first time a video game touched him in a way that made him cry."

"I think that these little games could play the role in online news sites that political cartoons played in printed newspapers," Frasca says. Frasca worked for CNN in Atlanta and has experienced the news business firsthand. He doesn't believe, however, that the world is ready for realistic news games. "I do not believe that there is, right now, a market for games based on the news. And [there's] even less [of a market] for a realistic depiction of the news, such as in Kuma/War. But I applaud their efforts, because they are taking risks, going where nobody in the gaming community has gone before, and even if they fail, their failure will help us all to better understand the relationship between games and reality."

Murray thinks, "the role of narratives is to explain the world and to communicate our solitary realities to others--to share our isolated experiences with others." To this effect, she says we put every medium that we encounter to that purpose. "We are always trying to tell the stories with more complexity, to capture more about the world. We're always trying to tell it more directly--to be more in touch with other people and to receive other people's realities more clearly."

The digital medium, Murray explains, "is a pattern-making medium that has absorbed the patterns of all previous media--visual patterns, temporal patterns (moving images), auditory, text--and it adds to that the patterns of behavior." This allows us to describe the world in terms of behavior. "So [the digital medium] does make possible a new kind of complexity, and then it seduces us with exactly the promise that you identify--that we could make something as complex as our own inner reality," says Murray. "That's what we're seeking."

But what about escapism? Is it a myth that we play games to escape? "Part of our reality is our fantasy," Murray says with a laugh. "That's our emotional reality. And it intensifies, paradoxically. The more it simulates reality, the more it can intensify our pleasures of escaping reality into an alternate reality."

Deus Ex Machinima

Film has wrestled with the issue of reality since the beginning. What's too much reality? What's not enough? What's the value of fantasy versus reality? Television is quickly approaching critical mass with its reality shows, but even there, the question "What's reality?" still exists. Lowood's How They Got Game project turns a cold shoulder on reality, as it were, by making it possibly as far from reality and movies as you can get. And there's a game angle, too.

For the uninitiated, and that possibly includes many readers, "machinima" has been around for several years, first appearing among Quake clans, whose many, various members were interested in making movies based on their game experiences. Machinima is complicated, but it is most simply defined as real-time, 3D movies in virtual worlds that are built on game engines. The term "machinima" is a hybrid of machine cinema or machine animation, or sometimes it's a combination of both. Those who have watched game cutscenes have seen machinima in action. Now these cutscenes, so to speak, have lives of their own. Machinima has slightly broken away from its game-oriented roots, in terms of the themes presented in the films, but it remains tethered to game mechanics, because game engines power machinima engines.

"The thing about machinima is there are things that are interesting to a general audience, but it does take some explanation to get to them. It's not familiar enough that people immediately see the issues," explains Lowood, who likens the medium to more of a performance-based experience like theater or, in some cases, television instead of traditional movies. "So, if it's just reduced to 'Why is it more interesting to just use real-time animation in a movie than to do it in a frame-based way?,' this discussion usually ends up hung up on the expense of it. That it's cheaper or something like that is not the most interesting discussion. What is much more interesting is the kind of community that is creating machinima [and the fact] that it is something that is accessible to people [and is created] relatively easily." Anyone with a computer can make machinima through a series of stages that, while too involved to describe here, are not actually too difficult. One way to conquer the medium is through Paul Marino's new book on the subject, 3D Game-Based Filmmaking: The Art of Machinima (Paraglyph Publishing, July 2004). Lowood also has more information on machinima in his article, High-Performance Play: The Making of Machinima.

Like the current digital film renaissance, machinima, because it is not expensive, allows a creativity and flexibility that Lowood says "you're certainly not going to see in commercial movies but you might see in certain types of digital video productions, experimental video, and stuff like that."

Lowood believes most people have seen machinima, even if they aren't aware of it by name. He says that machinima projects like Anna, created by Katherine Kang at Fountainhead Entertainment and winner of the "Best Technical Achievement" award at the 2003 Machinima Film Festival, is a machinima that viewers could watch without realizing it's machinima. It was generated by a game engine. "As the games become more and more like the quality of Pixar-level animation," Lowood says, "it will be easier for people who've been brought up on those standards, so to speak, to view machinima." Lowood doesn't believe most machinima, at this point, is like Anna, which is a high-quality, dramatic movie about the dismal life of a flower. Most machinima, as of now, is based on game battlefields and is chock-full of "in jokes" from the particular game's community. "There are a lot of conventions and tricks, which [dictate that] you have to know a little bit about the game to appreciate," Lowood explains. "And that's a little bit of a barrier for a wider dissemination of the medium, but that's going to change pretty fast, I think, as what can be done with machinima gets more sophisticated."

The goal of Lowood's Machinima Archives is to act as a permanent repository for documenting the history of machinima moviemaking.

There is promise in machinima for the future of games, film, and narratives. There's true innovation that could affect both other media and the way we play games and experience stories. "If you're talking about real-time animation," Lowood explains, "there are things you could do, like think about getting away from this 'third-eye' perspective that movies have given us, to being in the scene in a sense of assuming the point-of-view of any of the characters in the scene. This absolutely has been a possibly with machinima."

Lowood describes a cinematic future where viewers (or even gamers) can move a camera around to any of the characters, because the engine is generating the action based on the parameters the viewer specifically gives. "The information about who was where and where they were moving and all that--and the associated audio files--[is] not going to change. So you could think of movies that were put together not from the traditional, neutral point of view of a camera that cannot be changed, which is entirely the director's choice, [but from the standpoint of] making a machinima movie and deciding [that] 'I want to be character A or character B' [to] then see everything that happens from that character's perspective," Lowood suggests.

Machinima's roots in the game demo stemmed from this premise to see the action from the point of view of the best player of a game. Novelists such as Irvine Welsh and Gregory Maguire have experimented in print with the concept of switching away from the perspective of the main character's voice to that of others, yet the concept seems more stagnant in print as opposed to digital media, where the possibilities seem endless.

But will game and film fans come to machinima? Will machinima, which relies on game engines, redefine games themselves? "Historically, new media has always wooed older media," says Frasca. "When television started stealing audiences from film, movie theaters tried to make larger-than-life films, developing techniques like 3D or giant screens. I think that movies are trying to offer some of the thrills that originate in the world of video games and vice versa," says Frasca, adding that reality TV and movies like The Truman Show and games like The Sims all respond to a similar trend, albeit in different media.

Lowood thinks games can provide just as significant an experience as machinima, but the game experience might not be as much of a narrative experience as the machinima experience would be. "The game experience aesthetic might be, in a different sense, something about how our senses relate to each other, such as Dance Dance Revolution," Lowood suggests, "taking it to a very aesthetic dimension where you're relating vision to music and movement. It might be an aestheticization of politics or life to a simulation, with some kind of notion of what might happen if you distorted reality in a certain way." He goes on to further say that games, in this way, could be more experiential than the machinima experience, though they could be more "interactive" to a certain extent if multiple points of view are enabled, which is more narrative-based.

Under the Influence

One trait of a game, according to Murray, is that a game is without consequence in the real world. Yet some of the most heated game discussions in academia focus on simulation and the boundaries of reality in games. We can learn from games, and that makes them appear dangerous to some and glorious to others, depending on the perspective and the experience.

Beyond the fun they provide, games also "transmit ideas and values," according to Frasca, who believes that this is what makes them attractive to groups that share "strong views...such as artists, political candidates, advertisers, Hezbollah, and the US Army." He sees games as having evolved to a "more respected communication genre," which allows us to go beyond explosions and car chases and into the realm of exploration of human nature. Again, the popularity of games like The Sims emphasizes this point.

Three decades transformed video games from singular tasks with barely identifiable characters to scripts with fully formed humans, complete with emotional motivations and lifelike reactions. But still, are they serious? "Dead serious," says Miller. "It's a huge industry, but outside of the academic community, I don't see how people can accept or understand it as anything but a role-playing-game theater."

Why do people worry about issues like violence in games if games are only role-playing theater? People who don't study, or at least observe games in a dedicated way, try to bridge consequences of the real world to game playing, particularly in the area of violence.

Murray says we can't dismiss these concerns. "I think that there are two fallacies. One fallacy is to assume that imaginative behavior is equal to behavior in the world. I think that's a really profound mistake," she says. "But then there's another mistake, which is not to take into account that in interactive environments, we don't just watch and identify and do things within our minds. We do take action in an imaginary world, but we are enacting something." Murray explains further how she is not a "dog-loving person," but after petting her virtual dog onscreen by moving her mouse in Petz, a pet simulation, she became more affectionate toward dogs after modeling this behavior. This is partially due to the fact that the pet simulation offers a "dramatically compressed experience," Murray says, "abstracted from the world of consequence, [which includes things] like dog poop."

Games can certainly inspire behavior and teach us, but this is not to say they make us violent. In some cases, though, such as in the game America's Army, perhaps inspiring behavior is just enough. "We, as a civilization, are only beginning to understand [that] games are not just vehicles for fun; they also communicate messages," says Frasca. "The military understands this very clearly. America's Army is not just about fun, but also [it is] about conveying a certain idea of how life is in the US Army."

Frasca says that no one expected Dean for Iowa to be the next Tetris and that addiction was not the main goal. "There is no such thing as an ideologically neutral video game. To different degrees, they all show a certain way of looking at the world. The Sims, for example, shows homosexuality as a normal lifestyle. However, it does have problems with showing nudity. Those little design details are communicating ideas, even if the designers are not aware of them."

Lowood's extensive background in the study of military simulation gives him an analytical eye for the current trend toward military-infused video games and the ever-growing military-entertainment complex. In essence, Lowood agrees with Frasca in that designers may not be aware of the subtle communication messages games are sending but notes that this is only one side of the issue. Frasca is approaching the issue from more of a critical media perspective, according to Lowood. "I'm more from a history of technology perspective," Lowood says. "I would look at it as not just the content, but possibly, maybe, the technology is not fully understood and that this technology is still being negotiated in many ways." Lowood explains that the people who create and play a technology negotiate what a game actually is. By negotiation, he means--as in The Sims, for example--it may be that a life sim has been created, but the people creating the game values of the people creating that technology "may or may not include things that actually happen in real life as part of that simulation." A political or gender issue, for example, may be left out, because the creator's notion of the technology may not include simulating those issues. Taking this even further, Lowood suggests that the inclusion or exclusion of such features could be a "purely technical" issue. "In America's Army," he notes, "[you] may recognize that cowardice is an issue on the battlefield, but the technology itself is not able to present that richly enough and with enough subtlety that it can be included in the game." So it's a technical decision, because games technically can't deal with representing emotions like that.

Another angle is that perhaps developers know exactly what they're doing. Would the US Army be happy with an America's Army game that failed to inspire anyone to sign up for military duty? Would that be considered a successful game? It is difficult to remove the actual technical merit of the game from its underlying message that Army life is exciting, takes patience, and can be attained by anyone who can walk and hold a controller. Technically, America's Army is a good game.

Lowood asks hypothetically if there's any reason to be more concerned about America's Army than Grand Theft Auto, "which is also set in a contemporary society--a quasi-realistic society--and features probably more violence and certainly antisocial behavior. I don't know in that case if games like America's Army are more troubling," he says. Lowood suggests that America's Army provides young people, who are detached from what military service is actually like, with an impression of life in the Army. "I think, from the Army's point of view, the benefit is not just recruiting but weeding out people who wouldn't benefit or thrive in that kind of environment," Lowood says. "It's not quite a neutral communications tool. I wouldn't say that. But it's also not quite simply a recruiting tool, which would be something that would just be trying to pump up numbers of recruits."

Murray made her son's day-care center change its television policy, because the kids were watching G.I. Joe. (Please understand that she is the kind of parent who forbids toy guns.) She mentions a story in her book, Hamlet on the Holodeck, where she visited an arcade with her kids and walked up to a Mad Dog McCree game. "It's a very corny narrative that imitates the kind of television westerns that I watched as a kid in the '50s. And I looked at it and knew that all my life I'd wanted to play this game. I stepped up, and I was shooting this toy pistol at the outlaws, and I was really enraptured, putting in quarter after quarter," Murray says. "My children came up to me, dumbfounded, and I can still see their looks on their faces."

After the arcade experience, Murray's husband rented the television console version for her, but to her it "wasn't any fun at all. I had no interest in playing it." Apparently, the game had lost its visceral effect in translation. Murray says that what she learned from the experience was that "two different values systems could coexist and be equally authentic. And I felt like I had to confront that." But it didn't make her more comfortable with G.I. Joe, which, to her, "still raises the issue of recruiting boys into the military."

To explore the violence issue firsthand, Murray hired a friend's son to help her research the game Deus Ex, a game known for offering players a choice of how to play through by using either wit or force. Murray challenged her young researcher to play through the game without killing. "He really wanted to please me," Murray recalls, "but he could not bring himself to play it in that way. He was challenged to do it, so he liked figuring out how to get very well armored and how to use stealth, but he looked me in the eye, and he said, 'But if I do that, I don't get any of the weapons.'" Weapons are the holy grails of games, especially the hidden ones. Years later, Murray's researcher joined the military. She asked him if the Deus Ex experience prepared him for his military experience, to which he replied, "Yeah. It's a lot like that."

Marshall McLuhan referred to new media as an extension of our humanity. By this assumption, it could be argued that games have become more violent as a result of our more violent culture. Murray says that this is an oversimplification. "How could we be more violent than we were when we were basically hunters or the prey of tigers? I think that violence is a part of human society. And I think entertainment forms reflect human society." Are games a scapegoat for the explanation of violence, especially among teens? "Yes," says Murray, "because of the novelty and [the fact that the] representation is terrifying, [and] because [they] remind us of how easily deluded we are."

Yesterday Miyamoto. Tomorrow Dalí?

Mateas suggests that video games today are representative of the notion of a 21st century "total art," just as opera was in the past. Machinima, it could be argued, is that much closer, perhaps. The shopping list of lessons academia teaches us about the future of games goes something like this: Unless imagination is unleashed, innovation will not flourish. Game developers should embrace the relatively short history of electronic games to dissect its parts. Languages should be created for design. Genres need expanding. Narrative and open-world environments with true freedom of movement and plenty of activity should replace wandering aimlessly until we succumb to scripted choice points and return to where we started. Our experts also teach that we think a lot harder about our gameplay experiences than we realize or care to think. Games could benefit from strong narratives. Gameplay should always be meaningful but not necessarily complex.

The question "Are games art, or are games literature?" is easily translated out of the academic and into layman's terms, "Are games graphics, or are games story?" Are games narrative, or are games simulation? Or are they something wholly different and as of yet undiscovered?

When asked to select one person unrelated to the field of games--famous or not, dead or alive--for a stint as a game developer, Murray chose Charles Dickens, "because [of] the creation of a complicated interconnected world, animating every corner of it, and winding things up and letting them play out together. I think he would have been a game developer." Murray says she also thinks Dickens would have been a filmmaker in 1940.

Frasca thinks that almost any major jazz musician would make for a good game developer but notes that "Miles Davis, The Game" would be "cool." "Jazz is about improvisation and about being playful," he says. "The closest thing that I have seen in games so far is the fantastic WarioWare. It is the gaming equivalent to Fantasia, the celebration of a genre that is beginning to be of true importance in people's everyday lives."

Lowood takes the question to the political arena and suggests Bill Clinton because "...political simulation, which was a pretty effective area in the early '80s, is just dead as a game genre." To Lowood, Frasca's Dean for Iowa game was more of a "job that was given to him by a political campaign" than a political simulation. "I was thinking of Clinton kind of as a shorthand for getting some politician involved in designing games," Lowood elaborates. "Let's do a really interesting simulation of politics using somebody who knows it at a really deep level. To get somebody who really knows politics involved in a political game would be kind of fun."