Meet Me Halfway: How Embracing Contradictions Can Create Better Games

Tom Mc Shea admires the beauty of compromise in a world of heated conflict.

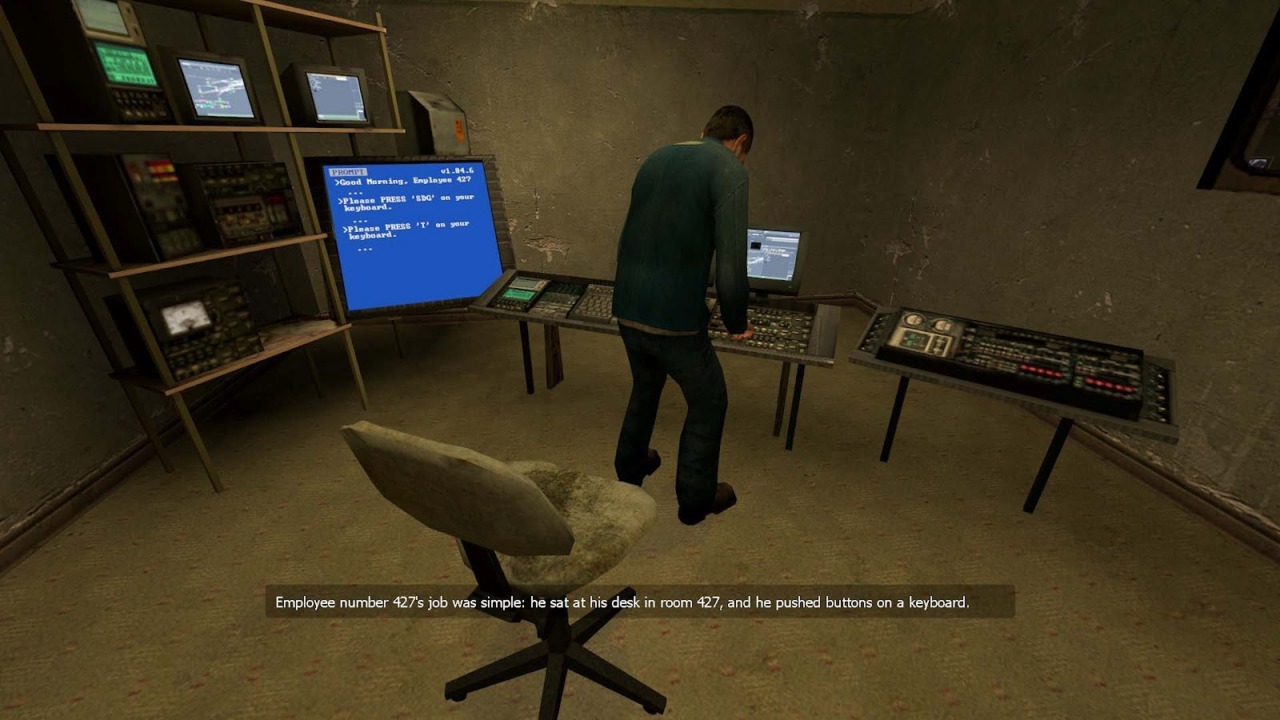

The advice was given in earnest. Trust your gut. Look for ideas everywhere. Don't form habits. Davey Wreden explained the tricks he had learned while developing The Stanley Parable at the Game Developers Conference, and the utterance of these simple-to-follow truths made the esoteric endeavor of game creation much more palatable. Never trust your first idea. Stop trying to find your game. Develop a creative muscle. Pens scribbled and heads nodded as Wreden verbalized the keys to success. He cautioned that, no matter how hard you try to separate yourself from your game, it's still going to be about you. And, please, resist the urge to let the game mirror your life.

As Wreden detailed everything that allowed him to craft his Half-Life 2 mod, knowing chuckles emanated from small segments of the audience. When he excused designers for stealing ideas--because every idea is stolen--and then, moments later, warned that you should avoid using ideas that others have already come up with, it became clear that Wreden was speaking with his tongue firmly planted in his cheek. Every bullet point that he went over had a counterpoint that canceled out the first. And yet, instead of this convergence of ideas creating a murky presentation in which no lasting wisdom could be gleaned, quite the opposite happened. The chuckles turned to riotous applause, and the audience walked away with a new appreciation for the creative process.

Please, resist the urge to let the game mirror your life.

Contradictions should not be shunned. Sometimes, both sides of an issue, no matter how far apart they may seem, could be true. And to understand the truth, the entire truth, you have to experiment, push yourself to see past your instinctual response. Although Wreden centered his talk on game development, his ideas can be expanded beyond his immediate intentions. Conflict can lead to resolution, or at least understanding, so instead of leading the battle cry for a black or white extreme, see what life is like on the other side.

Jay Posey, senior narrative designer at Red Storm Entertainment, delivered a GDC talk on an intriguing topic. In his presentation, titled Tastes Like Chicken: Authenticity in a Totally Fake World, Posey explained how his team infuses military shooters like Ghost Recon and Rainbow 6 with realistic elements while still creating within the confines of an entertainment product. A balance must be struck between authenticity and realism, Posey argued, which requires a deft hand. It's important to sift through all of the aspects that make up a war experience, remove anything that could ruin one's enjoyment, and amp up the fantasy angle that makes the prospect of being a soldier so appealing.

While hearing Posey extol the virtues of this skin-deep authenticity, my initial reaction was disgust. So much time is spent on making sure the lingo is impeccable and the guns are perfect, while the action is pure fiction. The good guys gun down hundreds--maybe thousands--of evildoers during the course of the campaign, regenerating health in mere seconds after being filled with a dozen bullets. If they should fall in battle, they respawn magically from where their corpses once lay, which eliminates the overbearing threat of death that plagues real soldiers. Nothing about the combat scenarios in military shooters screams authenticity. They are intent on maximizing fun, even though the real thing is anything but. Listening to Posey explain how to make something authentic when he's peddling the same bloodthirsty fantasy as so many other developers made my blood boil.

Remove anything that could ruin one's enjoyment, and amp up the fantasy angle that makes the prospect of being a soldier so appealing.

And yet, despite my firm belief that authenticity in war games should extend to the action, there is an opposite point of view from my angry perspective. And trying to understand both sides helps you to better appreciate the topic as a whole. Posey explains that developers should try to capture the flavor of life's battles without turning games into a simulation. The audience, Posey believes, isn't looking for reality; instead, games have to exhibit what people perceive happens on the battlefield. That means anything that could be considered boring should be downplayed, while developers should play up the exciting aspects. This is the philosophy behind creating the authenticity in many modern shooters.

Ultimately, both of these disparate positions are valid. Games in which authentic aesthetics loom large and imposing, overshadowing the fantasy present in the action, make up a healthy contingent of the industry's biggest games. Not only do franchises like Battlefield and Call of Duty set record sales numbers by using this approach, but they garner high praise from critics as well. Critical and commercial success; what more could you want? Well, the other side is unfortunately underrepresented. Aside from Arma, Red Orchestra, and a few others, there are strikingly few military games that dabble in authentic action. A balance should be struck, offering a grounded contrast to the over-the-top fare that currently dominates.

A similar dichotomy exists in the realm of video game violence. Walt Williams gave a talk at GDC titled We Are Not Heroes: Contextualizing Violence Through Narrative. The writer of Spec Ops: The Line argued that the more killing that your character has to do, the more run-of-the-mill it becomes. Kill enough people, and it eventually becomes filler. Violent games are creatively too easy to make, Williams believes. Instead of imagining in-depth mechanics that let you solve conflicts through talking or other nonaggressive means, most games let you shoot, smash, or otherwise murder your opponent, and this is a tiring, predictable outcome. Williams argues that the blanket use of violence is wrong, and developers should look elsewhere to tell their story.

This is one area where the industry has done a good job of pleasing both sides. Many games follow William's advice. The violence present in The Walking Dead, for instance, fits within the themes of the game, so it's much deeper than mere gratuitous bloodshed. However, Mortal Kombat still satiates one's craving for unrepentant gore. Everyone has games to flock to, because there is no right or wrong side to this argument. Furthermore, games in which over-the-top violence is a main draw often have worthwhile aspects beyond the carnage. Take a look at Metal Gear Rising: Revengeance. Yes, you can slice enemies into tiny pieces, but the reason the game is so exhilarating is the incredibly deep and flexible combat. Games still have a tendency to relish in their violent trappings (see the high kill counts in Tomb Raider and BioShock Infinite), but video game violence is a case where two fully realized, contrasting ideas have made for diverse and intriguing experiences.

Embracing contradictions can be a scary proposition. However, if you challenge your own beliefs, you may be able to understand the world more thoroughly. Wreden did a masterful job of showcasing how two opposing points of view can work in harmony. By following in those footsteps, developers could create more diverse experiences that push beyond the expected games that flood the marketplace. And, maybe most important of all, people might be able to discuss their opinions without inflaming the other side. That's advice we could all use.

'Got a news tip or want to contact us directly? Email news@gamespot.com

Join the conversation