Heroes Who Look Like Us: A Call for Diversity in Games

At GDC 2013, Halo: Reach writer Tom Abernathy argued that when games are more diverse, everybody benefits. Carolyn Petit thinks the time for such increased diversity is now.

Now, I don't want to look a gift horse in the mouth here. When Cliff Bleszinski blogged recently in defense of Feminist Frequency's Tropes vs. Women in Video Games project, I was glad to see an undeniably important industry voice taking a stand on an issue that I care about a great deal. His primary focus was on taking to task those who had responded to the Feminist Frequency project with vitriol, those who seemingly felt so threatened by the idea of someone critically examining the representation of women in games that they lashed out with slurs and threats.

Addressing those trolls specifically, he wrote, "Heaven forbid a woman actually take a magnifying glass to our beloved hobby and actually try to unravel and figure out why things are the way they are in the effort that somehow she might change things? Why aren't there more female protagonists? Are you protecting Lara Croft in the new Tomb Raider or are you empowering her? And god dammit, where's my Buffy game? Shame on all of you." I'm with him on this. The hostile reactions elicited by the Feminist Frequency project and other attempts to thoughtfully examine portrayals of women in games are embarrassing; they are a sign, as Bleszinski puts it, of "a deeper cancer plaguing our business."

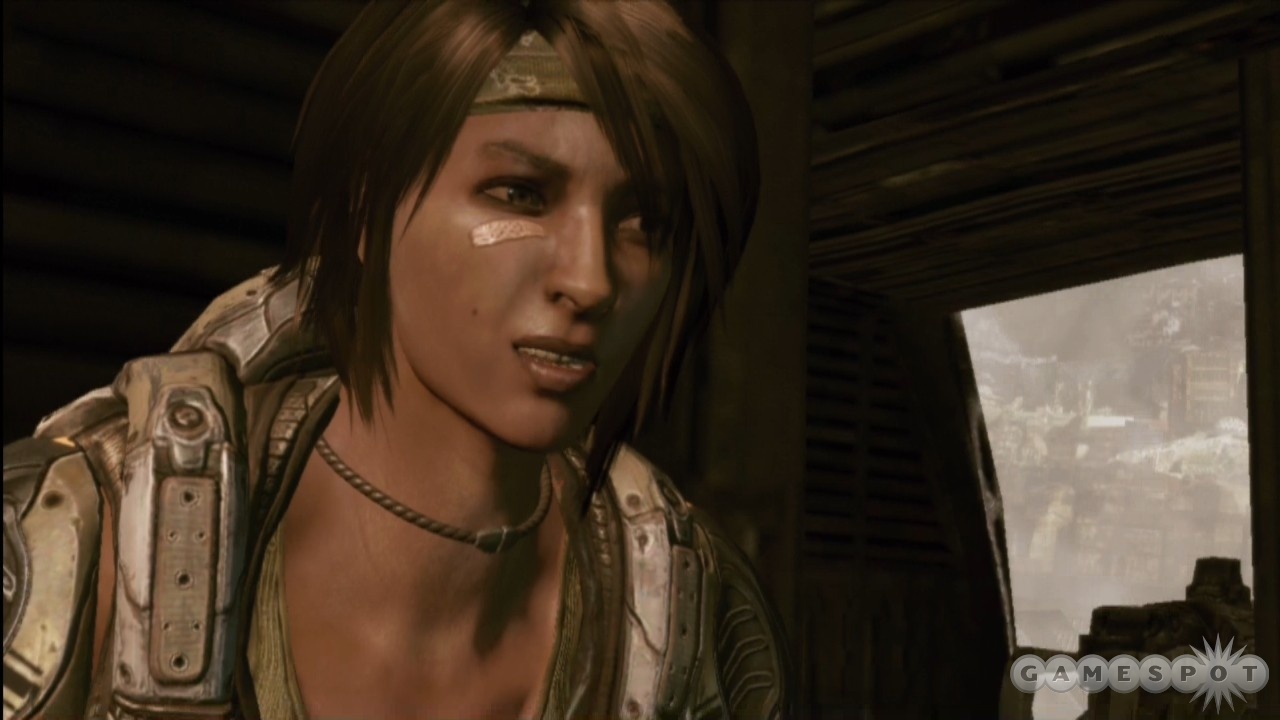

But I do need to take issue with just one thing Bleszinski states in his blog. Before launching into his spirited rebuke of haters and defending the value of examining representations of women in games, he asserts his own positive impact where women in games are concerned, writing, "I'd… like to remind everyone out there that I went out of my way in working with our team, the writers, and Epic's artists to make sure that female characters are represented well in that franchise. By the time we got around to Gears 3 the female soldiers were kicking butt right alongside the men in outfits that weren't drastically different than the men's, and with a restrained depiction of hair and makeup."

It's time for the heroes games give us to become more diverse, not in baby steps that coddle those who so adamantly oppose the idea of a gaming landscape that offers a wider range of heroes, but now.I'm sorry, but the fact that, by the time Gears of War 3 came around, there were a few playable female characters doesn't make that series an example of enlightened, progressive portrayals of women in games. Don't get me wrong; I'd rather there be women in Delta Squad in that third game than not. But why did it take so long? Why were women so marginalized earlier in the series, relegated to being, in Anya's case, mostly a voice in an earpiece or, in Maria's case, a victim of a horrific fate, more of a plot device to trigger emotions in one of the male protagonists than a character in her own right? On the whole, where women are concerned, the Gears of War series is pretty disappointing. Women have been so underrepresented in games for so long that there's a tendency to view minor gestures like the inclusion of a playable female character or two in the final game of a series as something praiseworthy, when really, the question we should be asking ourselves is, why weren't they there, as equally important, equally fleshed-out members of the cast from the series' inception?

It's time for the heroes games give us to become more diverse, not in baby steps that coddle those who so adamantly oppose the idea of a gaming landscape that offers a wider range of heroes, but now. Sure, the cancer Bleszinski referred to may respond to gradual treatments; over the course of the next 30 years or so, gaming could slowly continue to offer greater diversity in the gender, the racial and cultural backgrounds, and the sexual orientations of its heroes. But why wait? Let's just cut the cancer out right now.

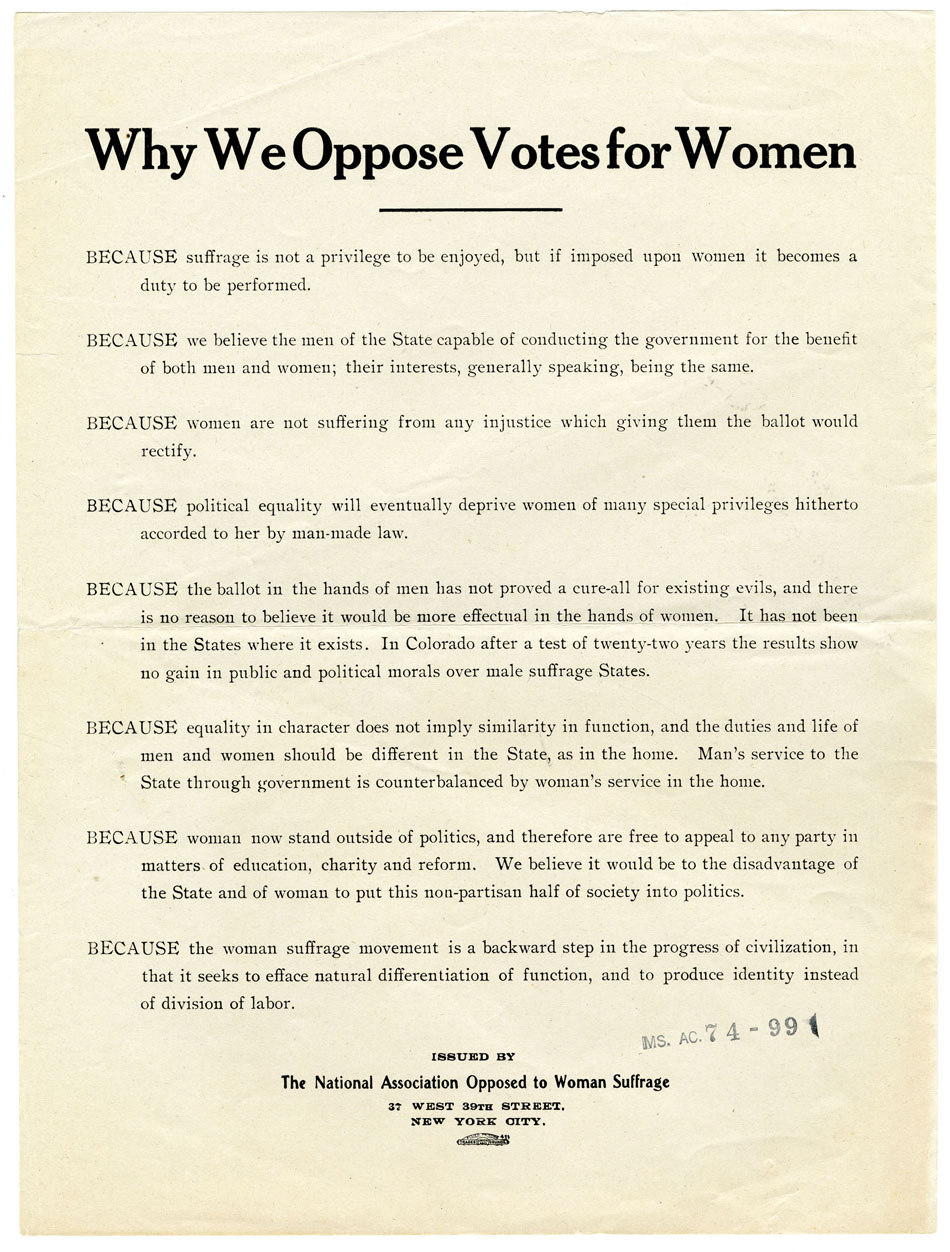

You see, the trolls and the anger they spew are not the cancer itself. They are a symptom. Having grown up with games that overwhelmingly feature heterosexual white men as heroes, some members of that group have grown comfortably accustomed to the status quo. Whenever there is a systemic imbalance that favors members of a certain group in any facet of society--voting rights for men and not women, for instance, or college admission policies that make it harder for students from low-income backgrounds to earn acceptance--some members of the benefiting group will not take kindly to attempts to wrest away their special status and make things more equitable. Whether it's done slowly or quickly, there will be resistance to the process of diversifying game characters from those people who not only like things the way they are, but feel like they are entitled to have things the way they are. But the reality is that this is not a zero-sum game in which there must be winners and losers. The straight white male video game hero is not going to go the way of the dodo; he's just going to have more company, and then, everybody wins. Straight white males of the future won't long for the overwhelming majority of games to focus on straight white males any more than most men today desperately wish that women had never been given the right to vote.

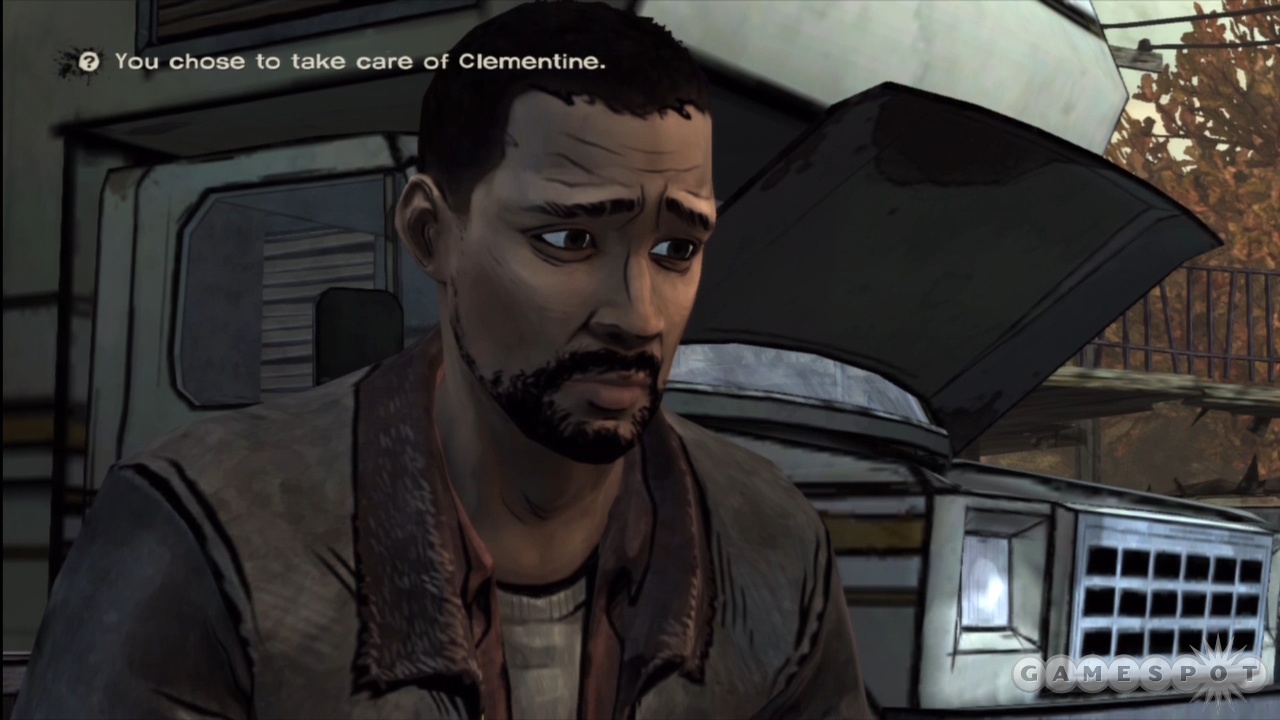

This week at the Game Developers Conference, Tom Abernathy, a writer at Microsoft Studios whose credits include Halo: Reach, gave a talk in which he espoused the notion that greater diversity in games would be good for everyone. Now, as a straight white male himself, he grew up with no shortage of heroes who looked like him, in films, on TV, and in games. And he never had much reason to stop and think about how many others didn't similarly have plenty of examples in media of heroes who looked like them.

In recent years, however, that has changed. Raising a daughter who, understandably, wants to read books, watch movies, and play games featuring girls has brought this issue into his life in no uncertain terms. We all want to see heroes who look like us, Abernathy asserted, and his daughter, who is also multi-ethnic, has as much right to such heroes as she grows up as he did when he was growing up. Unfortunately, Abernathy's quest to find games that would offer his daughter such heroes turned up scant results.

The straight white male video game hero is not going to go the way of the dodo; he's just going to have more company.Abernathy's talk was hopeful, but he acknowledged that diversifying the medium isn't as simple as just starting work on games with more diverse casts. He referenced a recent Gamesindustry.biz article about Remember Me, in which the developers stated that publishers told them they were unwilling to take on the game because of its female protagonist, and Abernathy said that he has heard similar conversations many times. You will face resistance, he said. But he hoped that his argument could give developers the leverage they needed to start fighting for greater diversity in the games being developed at their companies.

Abernathy's argument in favor of greater diversity in games was three-pronged. First, there was the moral argument. It is, he said, the right thing to do. There's no good justification for not doing it; everyone should have heroes who look like them.

Abernathy's second argument was about creativity. Diversity benefits creativity, he said, opening up opportunities for richer, juicier narratives. Looking at television, he compared the relative simplicity of the TV landscape of the 1970s to that of today. He argued that television is a richer, stronger medium now than it was then and that this was attributable in part to the presence of complex female characters like Homeland's Carrie Mathison, Scandal's Olivia Pope, and the numerous women of Game of Thrones. Why, his argument implied, would the creators of games want to deny themselves the potential for richer narratives that a more diverse cast of characters can offer?

But ultimately, the only thing that matters to businesspeople in a business setting is a business argument, Abernathy said, and if those businesspeople believe the core audience won't embrace diversity, they will counsel against diversity in games. So it was his third argument that was the most important: that greater diversity in games is smart business. He cited data that indicated that women and nonwhites make up a massive percentage of gamers. "Women are not a special market on the fringe of the core," he said. "Women are the new core."

Looking at the data, he said that it's not hard to see these trajectories moving forward, suggesting that the makeup of people who play games isn't going to get less diverse anytime soon. The audience is leaving us behind, he said; the market is changing faster than we are.

It was Abernathy's third argument that was the most important: that greater diversity in games is smart business.But his closing suggested that it doesn't have to be this way. An increase in diversity can lead to increased sales, he said, because games will be more relevant to their increasingly diverse players. As he made these statements, photos of his daughter kept his argument from being a purely intellectual one; it was a poignant call for a very important change our industry needs to make.

So let's do that now. Let's not put a woman or two in the third chapter of a male-dominated, woman-marginalizing series and call it progress. Will some people freak out if games suddenly get significantly more diverse? Sure, but they'll get over it. And those who don't, well, to hell with them. You don't coddle cancer.

'Got a news tip or want to contact us directly? Email news@gamespot.com

Join the conversation