Exploring the Ethics of The Castle Doctrine

Jason Rohrer's upcoming game The Castle Doctrine presents an ethically simplistic view of what are in reality some extraordinarily complex issues.

Is it possible for a game to be meaningfully critical of the role and mindset that it puts you in as the player?

This is a question I've been considering a great deal this past week, as conversations about Jason Rohrer's upcoming game The Castle Doctrine have exploded in some corners of the Internet.

As described in a 2008 filing by the New Jersey legislature, "the 'Castle Doctrine' is a long-standing American legal concept arising from English Common Law that provides that one's abode is a special area in which one enjoys certain protections and immunities, that one is not obligated to retreat before defending oneself against attack, and that one may do so without fear of prosecution."

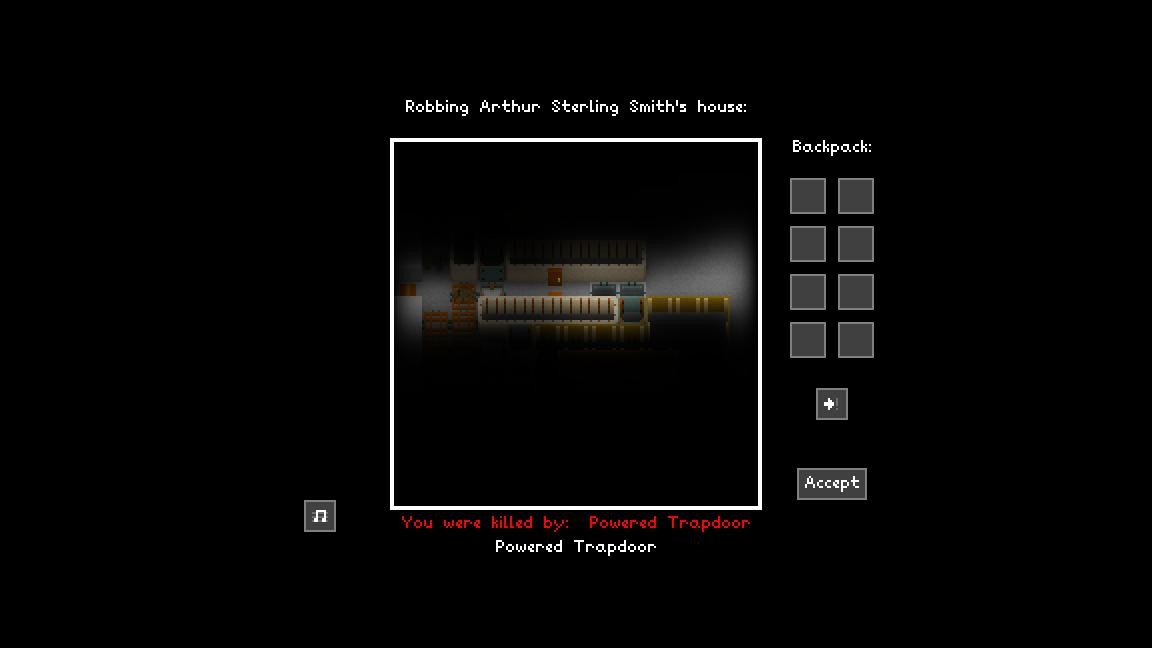

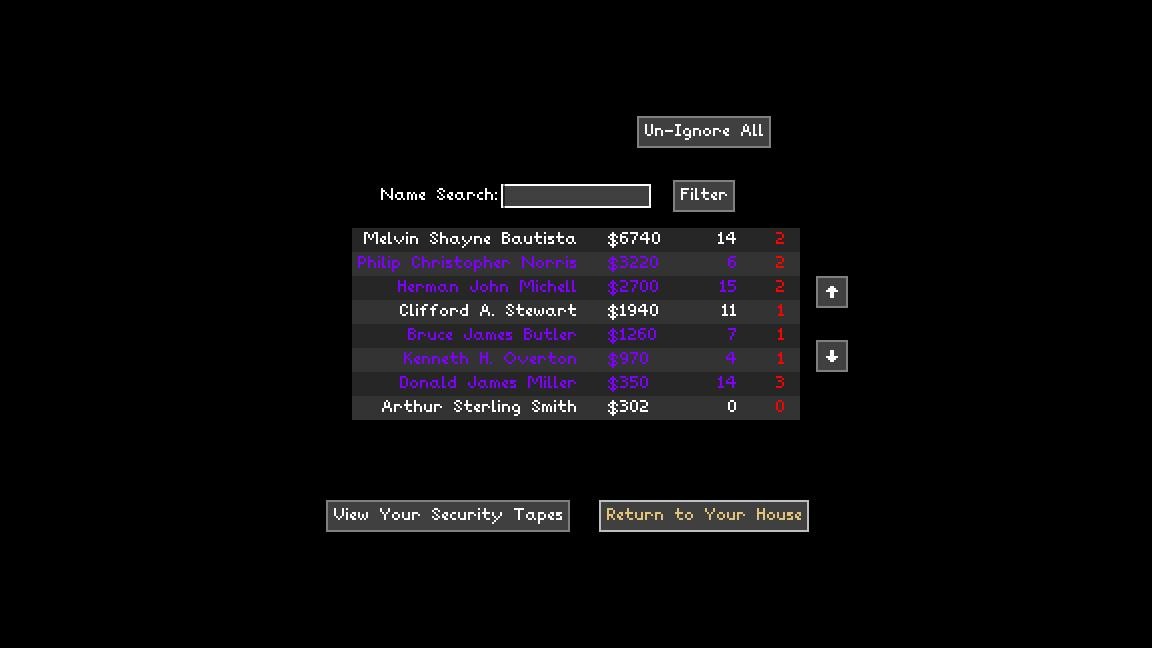

Rohrer's game, The Castle Doctrine, is billed as "a massively-multiplayer game of burglary and home defense." In the game, you play as a man with a house and a wife and kids you want to protect. To that end, you set deadly traps in your home to foil (and kill) intruders. To earn the money you need to improve your home's defenses, you must invade the homes of other players and successfully navigate the deadly traps they've set up in their homes. While you're away attempting to rob other players, they can invade your home and attempt to rob you.

In this scenario, why do you care about protecting your wife? It's not that you love her, though you may grow attached to her pixelated presence in your household. It's that she is your single most valuable asset. Specifically, when your home is invaded, she heads for the exit with half of your money. The invading player can let her go, or he can try to kill her before she escapes, and take that money for himself. So as a player, your wife is important to you because of her monetary value, and by that same token, you're incentivized to murder other players' wives to get the money they're carrying.

In the world of the game, everyone else really is out to get you; meeting trespassers in your home with deadly force is necessary and justified.The Castle Doctrine is an attempt to explore what Rohrer refers to on the game's official blog as "the social construction of manhood" in the early '90s. This strikes me as a noble and fascinating aim for a game. But how real can an exploration of manhood in that or any era be when a husband and father's sense of protectiveness over his family is motivated not by real love and concern but by financial interest? Surely, the value of most wives to their husbands, in the early '90s, today, and at any time in history, is not tied up in how large those husbands' bank accounts are.

In a piece about The Castle Doctrine on GameRanx called "Misplacing Value," Stephen Beirne articulates the problems with this design approach. "It's one thing," he writes, "to compare assault rifles by damage output and clip capacity. Designing a character in the same vein, as an application to be wielded and exploited, provokes a troublesome attitude. Mulling over a wife or a friend or a child with the same mindset as you would an accessory frames her as an extension of yourself and not a person in her own right." Also troubling is that your wife has no intrinsic value as a person; her worth--not as a person but as an object in your gameworld--is wholly determined by the net worth of you, her husband.

Perhaps more problematic is the paranoid mentality that The Castle Doctrine seems designed to foster. In the world of the game, everyone else really is out to get you; meeting trespassers in your home with deadly force is necessary and justified. You won't question if that player who was killed by your security system really deserved to die; you will know that he was in your home to take your things and probably to kill your family, too. But in the real world, this is a poisonous, insidious mindset that sometimes results in tragedy. The social theory known as the cultivation theory asserts that significant exposure to television, which generally portrays society as being considerably more violent and dangerous than it actually is, cultivates a belief that the world is more violent and dangerous than it actually is. Anecdotally, I remember how, as a child in Los Angeles who was exposed to far more local TV news than was good for me, I carried around fears of random violence almost constantly. And although this independently-produced game isn't going to have anything like the widespread cultural impact that television has, The Castle Doctrine seems designed to perpetuate this perception of society as extraordinarily dangerous, to make us see our fellow human beings as potential threats.

Can the game be critical of the dangerous idea that visiting deadly force upon those who scare us is reasonable, when it rewards you for doing just that?The Castle Doctrine also looks geared to be a misleading and dishonest examination of fear and paranoia in 1990s America. An honest examination of these issues would have to take into account issues of race and class, since the fears of what Rohrer refers to as "the burglar alarm generation" (the protective fathers of that period) were irrevocably tied up in perceptions of others that were impacted by race. Today, some 20 years later, little has changed in this regard. You only need to look at the court case concerning the death of Trayvon Martin to know that our society still treats the fears of some members of society as reasonable and justifiable even when those fears result in the death of an innocent member of another group.

And though George Zimmerman may have reaped the benefits of a law similar in spirit to the castle doctrine, as Cameron Kunzelman points out in his excellent piece "On Why I Will Never Play The Castle Doctrine," some are denied those benefits, even in cases where their defensive actions seem plainly justified. "The Marissa Alexanders of the world will continue to be imprisoned," Kunzelman writes. "The CeCe McDonalds will too."

But in the simplistic world of The Castle Doctrine, you're just a bunch of white men, all trying to protect your home from those who would violate it while simultaneously seeking to violate the homes of others. With this approach, can the game be critical of the paranoid mindset that its mechanics encourage you to inhabit? Can the game be critical of the dangerous idea that visiting deadly force upon those who scare us is reasonable, when it rewards you for doing just that? I think it's possible for games to be critical of the role they put you in as the player, but the only game I've ever played that I feel succeeds at doing so is September 12, a "newsgame" about the war on terror. In this game, shooting is not mechanically fun, so there's no visceral enjoyment in the act, and your attempts to eliminate terrorists only succeed in making more terrorists. To quote an applicable line from the film WarGames about the "game" of Global Thermonuclear War, "The only winning move is not to play."

Similarly, in the real-life game of fearing your fellow man such that you're constantly afraid, vigilant, and ready and willing to meet real or imagined threats or transgressions with deadly force, if you play, you've already lost. However, depending on who you are and how weighted in your favor or against it the American justice system tends to be, those on whom you focus your fears may pay a far higher price than you do. In The Castle Doctrine, though, you can be successful at killing home invaders, and at invading the homes of other players and murdering their families, and the game rewards you for your successes with money and tools that make you more capable of killing invaders and invading the homes of others. In this competitive space, you can win, secure in the knowledge that your fear of your fellow human beings is justified. This is a troubling perspective for a game's mechanics to endorse.

'Got a news tip or want to contact us directly? Email news@gamespot.com

Join the conversation