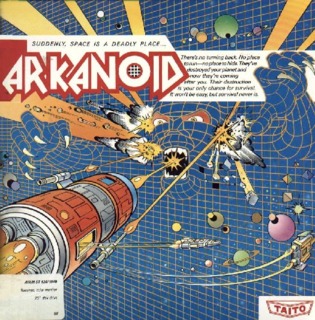

Firstly, it should be mentioned that Arkanoid is made by Taito Corp. instead of Atari. Taito could have done a straight Breakout clone, but it decided to build on what Breakout and Super Breakout have established by introducing some fresh mechanics into the genre, which will be elaborated later on in this review when convenient.

At first glance, it appears as if Arkanoid isn't really that much different from either Breakout game: there is a paddle and coloured bricks on screen that have to be cleared. Arkanoid may seem to be a graphical upgrade over either Breakout game, what with shaded sprites and implementation of an actual background image, but these would not be enough to impress skeptical players at the time.

Even the official description of the game's story, which is about a spaceship in the shape of a paddle escaping from some doomed mothership, would not be much of a substantial improvement over Breakout, which did not even need a story to be fun. In other words, the story in Arkanoid is really just a throw-away.

Like Break-out, players destroy blocks to gain points, with different colored blocks giving different amounts of points. Points can also be gained by destroying mobile, floating entities (more on these shortly), by either hitting them with the ball or crashing into them with the paddle (which is indestructible as long as there is a ball on-screen).

Reaching score thresholds such as 25000 points, 60000 points and so forth grants extra lives onto the player, though these lives are typically the level-resetting sorts, so the player has to knock down blocks right from the start of the level in which he/she has lost a life in. Again, this is not much different from Break-out.

However, once the player starts breaking a dozen or so blocks in the first level, the player would notice and soon appreciate the major differences that Arkanoid has compared to Breakout. However, not all of the game ideas are well-implemented, though they certainly do make Arkanoid feel reasonably fresh and different from Breakout.

The first of these differences is the apparently random release of power-ups when blocks are destroyed.

They impart various kinds of properties to the paddle, with only a couple of them affecting the ball. There are power-ups that elongate the paddle, making it easier to catch the ball (or balls), power-ups that triple the number of balls (and which may be a reference to one of Super Breakout's game modes), and power-ups that have the ball sticking to the paddle when they hit it, allowing the player to launch it whenever convenient.

The most useful power-up is the one that arms the paddle with blasters, allowing the player to actively destroy blocks without waiting for the ball to collide with them.

Considering that only one power-up may be active at a time, the blaster power-up may be the one that the player would most likely retain at the expense of anything else, which is a detriment to the game as it could have been more fun if players may retain more than one power-up.

Another major difference that the player would notice is that some blocks cannot be destroyed in any way, and these are represented as shiny golden bricks that shine and flicker when they are hit; balls simply bounce off them when they collide. On the other hand, these blocks need not be destroyed in order for the player to have progress in the game.

These are used to create some cleverly designed levels that have the ball bouncing around in very amusing manners. However, considering that the player has no control over the direction of the ball when it is away from the paddle, they may cause the ball to bounce uselessly around. There may even be rare occurrences where the ball is caught in an arrangement of golden bricks, bouncing around in an endless loop that effectively bricks the game session (pun not intended).

The third significant difference is that the game introduces entities that float around the level in seemingly random manners. These appear from gates at the top of the screen, and are completely optional to destroy, but they do impart additional points to the player's score and more importantly, they provide obstacles that the ball can bounce from, if they are solid enough.

These entities appear to have different sprites and animations, depending on the levels being played, but generally, all of them simply float around aimlessly. Eventually, they start to repeat as the levels wore on, making them less remarkable over time.

The most important change that Arkanoid has over Break-out is the programming that governs the speed of the ball. This is the game's most important feature, but also its worst-designed one, unfortunately, because it is tied to the score-gaining mechanics of the game.

The ball, when launched at the start of a level, appears to have a rather manageable default speed. However, it will eventually increase in speed, depending on the player's rate of score-gain, among other factors not clear to the player.

If the player strikes a sudden windfall of points, e.g. a lot of blocks are destroyed in quick succession, it gains in speed drastically, making it more and more difficult to catch with the paddle. The mathematics behind the gaining of speed in proportion with the rate of score-gaining are completely opaque to the player.

The floating entities are particularly likely to cause the ball to accelerate drastically; each hit appears to distinctly increase its speed.

At times, the ball simply speeds up on its own for little reason.

Retrieving the power-up that slows down the ball does not help much either; it is only effective when the ball is still at manageable speeds, but it is simply useless when the ball is covering the entire height of the screen in a second.

This speed-changing mechanic simply makes the game unplayable sometimes.

Arkanoid has a multiplayer option for two players, but it is the tacked-on sort that many NES games had at the time: both players take alternating turns to play the game, each turn ending once either player has lost a life. Considering the caliber of the rest of the game's designs, this is a disappointingly lacking feature.

Nevertheless, there were still other reasons for players at the time to play through the game anyway. Most of these concern references to other popular classic games and the companies that made them.

There are a lot of references to other classic games in Arkanoid; these can be seen in the layout of the blocks in some levels, such as one that has blocks arranged in the shape of an invader from Space Invaders. Some other levels arrange the blocks in the shapes of logos of well-known game-making companies at the time, which may have been to players of that time.

Finally, the most compelling reason to play the game comes in the form of a surprise in the final round of the game, which this review will not describe as it would constitute a spoiler. However, it should suffice to say that it inspired the designs of later Breakout-like games, such as Shatter, which is better known for its boss battles.

The music merely consists of a tune that plays during the start of a level; nothing plays during a level itself. However, the sound effects of the ball hitting blocks, destroying floating beings, and bouncing off the paddle, coupled with the warbling sounds for the retrieval of power-ups, would be enough to distract the player's ears with.

It can be a bit disappointing that ending levels simply results in a brief freeze before the next level loads, with no tunes or sound effects to congratulate the player with. However, there is an amusing tune that plays if the player happens to have the luck to obtain a power-up that simply opens a short-cut to the next level. (In addition, the player gains a massive infusion to his/her score.)

(There is also a catchy tune that plays at the end of the game, but it is rather brief.)

As a summary, Arkanoid has some noticeable flaws and the implementation of some of its ideas are far from perfect and may have even made the game more frustrating to play than it should have been. However, its game designs showed that the game formulas established by the Breakout franchise could still be built upon in quite a few interesting ways.