INTRO:

That a writer’s worst nightmare (or best dream; perspectives vary) which is what he/she wrote coming through is not something that is new. What is quite refreshing though is the same trope being mixed with another well-worn trope that is messages from the future, and then mixed with the plot tool of startling developments that forces even a jaded story-viewer to rethink his/her impressions of the story.

Alan Wake would do this. This title has been developed and is fully owned by Remedy Entertainment (the brilliance behind the acclaimed first and second Max Payne games).

In between story expositions in the game though, the player is treated to quite a lot of encounters with the nasty, supernatural sort. However, and fortunately, such fillers are made more palatable by an interesting system that has the player making use of light sources.

PREMISE:

Alan Wake is a depressed writer with writer’s block; this much is apparent from the start. He also happens to be a mercurial person. Fortunately, he has a wife who supports him and whom he cherishes very much.

The latest attempt by the couple to help lift Wake’s spirits has them going to a little-known but picturesque town in the forested countryside of (the USA State of) Washington. This quaint town, which goes by the name of Bright Falls, looks innocent enough, but eventually, Alan learns that there are terrible secrets about the town that would ruin his vacation.

That is an understatement of course.

LIGHT:

Very early on in the game, the player is taught that light is Alan’s best chance at survival. There are many sources of light in the game, but not all of them have the same effects and benefits for Alan. This will be elaborated later, because there are many sources of lighting that have a lot to do with the gameplay.

For now, it can generally be said if the player can spot a source of lighting, chances are that it is a haven for Alan. In fact, the game would make it quite clear that the player should move towards any bright source of light that he/she can see in the distance. It always happens to be where the player must go.

Harsh lighting is the player’s best weapon against the supernatural enemies in the game. Indeed, certain enemies can be defeated – or rather, must be defeated – by shining harsh light on them. Harsh lighting also hobbles more mortal enemies that depend on the darkness for unnatural feats.

LAMP-POSTS:

Lamp-posts finally get a high-profile role in video games thanks to Alan Wake. Where in other games in which they are little more than decoration in slower-paced games or collateral damage in explosively exciting ones, they actually have a purpose beyond the mundane in this Remedy title.

As mentioned earlier (with less cheesiness), light is Alan’s best friend against the darkness. In fact, the light from lamp-posts is seemingly capable of healing Alan - which is something that Alan would notice, much to his bewilderment. Only lamp-posts can heal Alan too – any other light source does nothing for his health (which the game does not inform the player about, unfortunately).

Furthermore, any working lamp-post also happens to be a one-time checkpoint; this will be something that the observant player would notice. Lamp-posts also dispel any nearby Taken when Alan steps under them, though they would not help much if he is being pursued by the more powerful of phenomena that the Dark can conjure.

PORTABLE LIGHT SOURCES:

Eventually, Alan picks up a flashlight, which is perhaps convenient considering that he would be wandering around in the (very dangerous) darkness a lot.

Firstly, it has to be mentioned that he cannot shine it on himself to heal from his wounds. It would have been convenient, but it would also have been unseemly silly.

Secondly, and perhaps to the chagrin of people who do not like product placement in games, the first flashlight that the player comes across is obviously an Energizer product. All of the batteries in the game that power portable light sources are also exclusively Energizer. Unfortunately, this is not the only product placement in the game, as will be described later.

Thirdly, any portable light source – there are more than just flashlights - that Alan picks up is magically capable of recharging itself over time, though the player can refill the flashlight’s energy immediately by popping in a battery. Alan can only have so many batteries at any one time, but any limit would be enough for a thrifty player that looks for other means of illumination.

Finally, any portable light source has two modes of illumination. Its default mode has it shining light on things like regular flashlights would. The other mode is also associated with aiming down the sights of weapons, for better or worse.

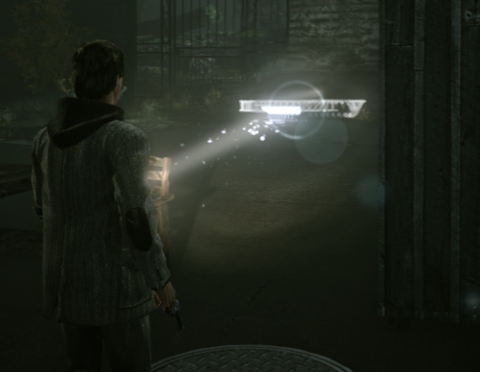

Anyway, in this alternate mode, the light from the device becomes more focused, exchanging its arc of illumination for a much more focused beam. The focused beam can zap the darkness; this process is beautifully, satisfactorily and conveniently indicated via a lens-flare-like halo that appears over the darkness-shrouded target. There will be more elaboration on the halo indicator later.

There are a few types of portable light sources, each with their own advantages and disadvantages, though these are not immediately clear. As an elaborative example, when the game introduces the heavy-duty flashlight with its much more considerable capacity, the player may think that it is a straight upgrade until he/she realizes that it recharges far more slowly than the regular one.

SEARCHLIGHTS:

Searchlights are Remedy’s take on the now ubiquitous “turret sequences”. As to be expected of turret sequences, Alan has to mount a turret, albeit one equipped with a harsh long-ranged light source to zap Darkness-imbued entities out of existence. Conveniently, it can remove even the Taken outright.

Typically, like the turrets seen in “turret sequences” in other games, the searchlight can “overheat” if the player has it in “focus” for too long. Therefore, the player will have to learn to stall encroaching enemies by focusing on them for a short time and alternatingly using its regular shine to pressure other enemies.

There are a few searchlight sequences where the Taken’s A.I. seems to be bugged. In these particular sequences (which happen late into the game), the Taken simply stand in place when Alan uses the searchlight. This makes them easy sitting ducks, which is a bit disappointing considering that these later turret sequences are supposed to be more difficult.

GUNS:

Shortly after getting a flashlight, Alan would obtain the Revolver, which is the only sidearm in the game. It is not very strong, but revolver bullets are the ammunition that he can carry around in the greatest quantity.

Moreover, the revolver will be the weapon that has the player realizing that there is no targeting reticule for the player to use for aiming, at least by default. If Alan is not focusing his flashlight on something, he fires shots in the general direction in front of him. There are some auto-aim scripts that have Alan hitting any target that is in the vicinity of the centre of the screen from the perspective of the player, but generally, his accuracy would be unreliable when not aiming down sights.

He can aim down sights for improved accuracy, but the same command input to do this is also used for the flashlight focusing. This means that the player could be wasting flashlight energy on Taken that already have their shadow buffs (more on this later) taken away. A separate input, or a toggle to disassociate these inputs, would have been much appreciated.

Soon enough, the player is introduced to the shotgun, of which there are two variants: a double-barrelled one that can unload its two shells very quickly, and a pump-action one that fires a lot more slowly but has capacity for more than just two shells.

The player will also learn that shotgun shells are rare, especially when compared to the more numerous revolver rounds.

Switching between the two different shotguns will also reveal that Alan neglects emptying the chambers of the discarded shotgun. Considering how rare shotgun shells are, this is a dissatisfying oversight.

More than halfway into the game, the player is introduced to the hunting rifle. It is a powerful gun, capable of knocking out most vulnerable Taken with one shot each. However, rifle rounds are much rarer than shotgun shells and the hunting rifle competes for the same weapon slot as the shotguns.

Although most of the guns in the game would seem all too familiar to veterans of shooters, they will come to learn to appreciate them, mainly because the game is not forgiving on those who waste ammunition

Furthermore, every now and then, Alan would find himself without any weapons and would have to find new ones all over again. It can seem tedious, but it does make the player feel vulnerable, as the game designers intended.

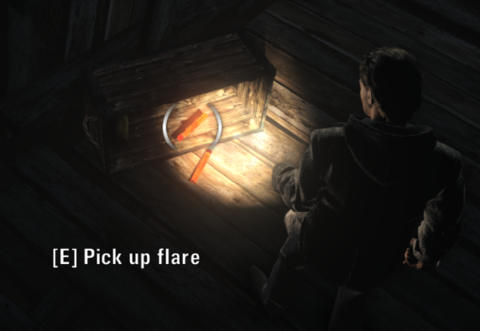

FLARES & BANGS:

Considering that harsh lights defeat the Dark in Alan Wake, devices that emit bursts of light practically fill the niche of the explosive weapon archetype in this game.

The most exemplary of these is the flare gun. It launches a flare that explodes brilliantly when it hits something, knocking out all nearby Darkness-infused entities. Even the Taken does not need to be shot down; they simply disintegrate if they are caught in the blast of an exploding flare. Some entities are tough enough to take more than one, but conveniently, Alan can stock quite a lot of shots for the flare gun.

A player that is experienced in shooter titles may be tempted to consider the flare gun to be the equivalent of a rocket launcher. Furthermore, the flare from the flare gun temporarily illuminates the area where it lands after having exploded, thus acting as an area-denial weapon too.

The other devices that temporarily emit light are akin to incomplete flare gun shots, but they fulfill their own tactical niches.

Regular flares can be popped and dropped to create a small temporary haven from the Taken; even the ones that toss axes would not toss their axes into the light of the flares.

Flashbangs are practically frag grenades when used against the minions of the Dark. Any enemy will suffer tremendous damage if they are caught in the vicinity of the explosion. However, Flashbangs are rather rare, and they take a while to detonate.

SUPPLIES:

Guns, ammunition and other supplies are located in various places throughout the game’s levels. Usually, these caches are indicated by structures such as shacks or crates lying about. More often than not, there are also emergency cases with supplies that are located near Bright Falls’ lamp-posts. Sometimes, there are even massive ammunition crates with unlimited amounts of ammunition.

That supplies are at convenient locations may give the impression that Alan Wake is yet another game with expedient game designs. However, there is a story-related explanation for this; although it is not entirely convincing to those who are sceptical, at least the game designers made an effort to cover plot-holes.

(Speaking of plot-holes, it would appear that the game designers are aware of some of these; this will be elaborated later.)

This explanation is also used to justify a side-game of finding hidden caches of supplies, which often include flares and flashbangs. However, it has to be mentioned here that the game utilizes these too for jump-scares.

SPRINTING & DODGING:

Alan Wake is not an athlete and neither is he a seasoned fighter, it has to be said. However, he does have an uncanny ability to dodge incoming attacks.

For now, it should suffice to say that with a simultaneous tap of two buttons – one for the sprint command and the other a directional input – he can start a sprint by making a dodge move. This can be odd to look at initially, but eventually the player would learn to appreciate it because it allows Wake to dodge an incoming attack before starting on a sprint to prevent himself from being surrounded.

He cannot sprint very far though. Once his stamina runs out, which is indicated by a clear slow-down, he will become exhausted and if the player pushes him on anyway, he simply stops to catch a breath. This is of course not desirable when he is being chased by more Taken than the player could handle.

It is not always clear for how long he can sprint, but his stamina appears to increase through the course of the game. A certain type of collectible might be associated with this game mechanism, but if it is, its effects are too subtle to make strong correlations.

Unfortunately, many enemies can sprint too. A certain type of the Taken, the one with scythes, is even fast enough to catch up with Wake. The player may have to learn the hard way that holding down the sprint button is not the only way to save Wake. (The player will need to stall them by focusing the flashlight on them occasionally to put them in a stun animation.)

THE TAKEN:

The “Taken” have already been mentioned a few times earlier in this review. They form the main bulk of enemies that Alan has to face.

They are both interesting and disappointing, unfortunately. At first, the game mentions that they are unsuspecting mortals that had been possessed by the Dark that is hunting down Alan Wake. Yet, the game resorts to tertiary characters that are not featured prominently in the story to form the bulk of the victims of possession. (To clarify, many of these characters are described as illegal poachers and loggers and hillbilly farmers that are not necessarily part of the Bright Falls community.)

This may somehow justify the fact that most of the Taken are armed with farming and logging tools, but when characters such as policemen appear with axes and sickles too, their designs would begin to feel contrived. To cut the game designers some slack though, the designers have mentioned that they have tried using enemies that are armed with guns and the consequence of this experiment is a sharp increase in difficulty due to the need to remove their shadowy shields, a process which requires Alan to move slowly.

Speaking of shadowy shields, these are the protection that the Taken has, which renders them quite immune to gunfire. The player is informed about this early on through some hapless unnamed bloke who learned this too late.

Interestingly though, the player is not informed that the stopping power of gunshots is not blocked completely by the Taken’s shields. Gunshots can knock them down or stagger them a step backwards, in the case of the brutes. An observant player would realize this, and it is certainly a handy lesson to keep in mind when the game introduces environmental hazards.

Anyway, the player usually has to remove their shields by shining light on them. As this happens, a visual indicator that resembles a halo appears over any Dark-infused entity that is being illuminated. The halo shows the progress of removing the shield of darkness that a Taken has by shrinking in radius. Once it shrinks enough, the shield explodes and fizzles out of existence, leaving the Taken temporarily stunned and vulnerable to more worldly means of destruction.

Whether they have their shields or not, light annoys and slows the Taken down; this is something that observant and skilled players would notice and exploit. For example, an onrushing Taken can be stunned by focusing the flashlight on him, effectively cancelling his current animation.

However, if the player alleviates the pressure on the Taken, its shield will replenish. On the Easy and Normal difficulty setting, this happens slowly enough that it is not an issue, but on any higher setting, this is indeed worrisome (among other sources of worry such as Alan having less health and they having more health).

The experience of eliminating the Taken may seem refreshing at first, but eventually the experience can become stale because the game recycles encounters with the Taken many times over. Certain scenarios and their increasing numerousness and danger stall this process, but for many players, the Taken are more likely to become annoyances later.

That the Taken can be generally lumped into several archetypes accelerate this process. The player is introduced to the “axe murderer” archetype first, something that the game would do with a reference to a certain infamous movie with Jack Nicholson in it. He is the most straightforward Taken to deal with.

The axe-throwing Taken are the next kind of Taken to be seen. They appear to have an unlimited supply of axes, probably thanks to their shadow buff. However, if this is indeed the excuse, then it would be understandable that the axes that they throw can be burned out of existence if the player is quick enough to focus the flashlight on them.

Later, there are sprightly Taken that always attempt to attack Alan from the side or rear. Next, there are the obligatory brutes with charging moves.

Some particularly troublesome Taken appear to be introduced as bosses at first, but eventually the game replicates more of them to increase the difficulty of later combat encounters.

If there is anything convincingly refreshing from the Taken, it is the inane and unsettling things that they utter when the game announces an encounter (usually by slowing down time and taking over the camera to provide a cinematic pan).

To cite some examples, there is a certain enemy that mutters warped versions of otherwise innocuous house-renting policies, and another that warns about the cancer-causing effects of graveyard shifts for jobs (which is apparently an actual World Health Organization 2007 report in the real world).

Listening to their utterances would have been entertaining, if not for their relentlessness in hunting down Alan. Moreover, other noises, especially the ambient noise, can easily drown out their mutterings. However, most of the time though, they do not utter anything, especially when the game resorts to spawning them at locations where they can ambush Alan.

POLTERGEISTS & RAVENS:

The Dark does not just turn people insanely homicidal and super-powered. It can also permeate into inanimate objects, turning them into massive projectiles or make-shift yet implacable barriers. The game refers to them interchangeably as the “possessed” and “poltergeists”, though the latter is perhaps more fitting.

Unlike the Taken, they cannot be gunned down. Instead, they have to be defeated by illuminating them, after which they zap out of existence. The bigger objects take longer to be eliminated, which makes them even more dangerous.

The challenge that poltergeists pose greatly depends on the openness of the environment that Alan is caught in. Since the poltergeists often inhabit massive objects, they can be blocked by many things, including other poltergeists. In fact, more experienced players would exploit the indestructibility of certain environmental objects, such as rocks and fences to block them.

However, getting hemmed in by poltergeists is pretty much a game-over. Since they are Dark-infused, Alan is damaged by merely touching them.

In more open environs, poltergeists are substantially more dangerous. However, observant players may notice that they have limited ranges of detection; if Alan is too far away, they do not activate. On the other hand, it is more than likely that Alan is too far away to illuminate them with anything.

Perhaps as a reference to certain horror-story tropes, the Dark can also inhabit animals – ravens to be specific. They are there as an archetype of enemies that perform aerial assaults.

Initially, having to fend them off may seem exhilarating at first, at least until the observant player notices that the ravens ‘cheat’ in a few ways. Only the geometrical centre of the murder of ravens has collision limitations; the birds in the fringes of the formation pass through solid objects like they are not there. Fortunately, the player can still funnel them by reducing the angles at which they can attack Wake.

LEVEL DESIGNS:

Remedy has done a lot of research into creating a quaint town in the mountainous regions of the USA. Such efforts show through the visual designs of Bright Falls and its abandoned industries, as well as the personalities of its inhabitants, most of whom would never see anything beyond their town.

However, upon the player’s attempt to see if he/she can explore Bright Falls at his/her own pace, the imagery can fall apart rather quickly. Many levels are linearly designed; they funnel the player character down paths towards the same destination by placing unbelievably insurmountable obstacles in Wake’s way, such as waist-high fences that are really invisible walls that reach up to the skybox.

Indoors, the game resorts to using locked doors, yet there are some jammed doors that Alan simply ram through.

Speaking of ramming, Alan often exhibits a ludicrous amount of strength throughout the game, being able to crash through doors, kick wooden obstacles into smithereens and push carts full of scrap metal easily. The game missed an opportunity to elaborate on this peculiarity – or at least make fun of it. Such scenarios also give rise to the suspicion that these obstacles have been included to mask loading times.

Some levels are little more than fillers, such as the levels in which Alan has to navigate through abandoned mines. Perhaps there is a little novelty to these locales, such as cramped spaces in the case of said mines, but this would be little different from what the player experiences from the other levels.

However, the developer commentaries do provide the reasons for these limitations, the biggest of which is that Remedy’s designers are not fantastic enough to work miracles with level designs.

Remedy does not have any excuse for the high frequency of combat encounters though, beyond what has been mentioned in the story. Perhaps the relentlessness of the Dark is already a good enough excuse, but players who look forward to the next story exposition would have to trudge through combat that may not seem too different from the last.

Of course, it can be argued that the game designers have custom-designed combat scenarios to the locales that the player would come across. However, a type of locale, such as a farm plot may well be reused a few times such that the experience no longer feels special but rather formulaic.

That such levels are often bounded by cliffs, rocky outcroppings and wreckage add to the impression that some levels have been designed in a contrived manner. (Of course, one can argue that the settings of the game do give an excuse to the presence of such level boundaries.)

There are levels that are more open; these usually occur in daylight, which is a pleasant contrast to the usually tense and ominous night-time levels. With that said, these levels are mainly intended to showcase the beautifully detailed countryside that Remedy had designed.

However, there are still contrived designs in these levels that will quickly quash any impression that these levels are open-world environments. For example, there are immovable vehicles that block off tunnels and indestructible fences that wall off roads.

If there is any gameplay value to be had from these daytime levels, it is that the player is given a calmer setting to look for collectibles. In other words, most of their value lie in their sense of immersion.

COMPANIONS:

(This segment is mainly about the gameplay designs of companions; any themes or story tropes that are associated with them are described in another section.)

Alan Wake is not always alone in his struggle against the Dark. For a few levels, he is accompanied by others and has to rely on them to get past obstacles or enemies – whether he actually likes their company or not.

That is, unless the companion is Barry Wheeler. For most of the game, Barry is useless and is mostly there for comic relief, though it is very good comic relief. He appears to become more useful in the final episode of the game, but the A.I. scripts for his offensive actions are too conservative for him to contribute to the firepower of Alan’s group.

Other companions are a lot more capable at defending themselves. Moreover, they happen to have unlimited ammunition, so the wise player that realizes this would exploit this to save Wake’s own ammo.

Indeed, the very first companion that the player would come across is the only one who is armed; in this scenario, Alan must help him burn off the shadow shields that the Taken has, in addition to directing his fire.

Later in the story, the game uses the presence of armed companions as an excuse to increase the severity of the opposition by the Taken to levels that would have overwhelmed the player if Alan was alone. There would not be much of anything new that a player who has experienced many shooter titles with A.I.-controlled companions would not have seen.

VEHICLES:

There are vehicles in the game, though one would wonder whether they are there to enrich the gameplay or as part of Remedy’s product placement deals (more on these later).

Vehicles are practically weapons to be used against the Taken. The player can focus their headlights to zap off their shields from quite far away, and then ram them with the vehicle to add injury to insult. However, all vehicles have limited durability (with the SUV ones being the most capable at taking punishment), so a prudent player may want to consider simply using the vehicles to get away, if possible.

Anyway, the fun that vehicles provide would end sooner or later. This is because any level with vehicles would have indestructible obstacles that eventually force the player to abandon his/her ride and move on foot.

Unfortunately, there are a few issues with vehicles. The chief one is that the camera attempts to automatically pan back to give a view of what is in front of the vehicle whenever the player has the camera looking away elsewhere. This can cause dizziness.

Another issue is that many of the vehicles feel too light. Those that do not are lumbering things that are very difficult to turn around. Indeed, most of the automobiles in the game are difficult to drive, especially at fast speeds. That the countryside of Bright Falls is not conducive to driving either further adds to the severity of the issue, so much so that vehicle-driving can feel out of place in the game at times.

COLLECTIBLES:

There are some items that act as rewards for players that have the nerves to go off the beaten path – straight into the oppressive darkness – to explore the levels.

In addition to hidden caches of supplies, there are collectibles with seemingly no immediate gameplay benefit when retrieved.

Chief of these are manuscript pages, which are tied into the story more tightly than the other collectibles are. These grant the new player some insight into what is going to happen next.

Some of the manuscript pages are only available in the highest difficulty setting of Nightmare. Although one can argue that these pages would no longer be as useful as those that were encountered for the first time, they do contain mentions on what other characters did off-screen. Of course, such an incentive is only lucrative to players who are particularly interested in the story.

Other meaningful collectibles include listening to radio broadcasts and watching TV shows to their completion. These have something to do with the writing for the game.

Next, there are thermos flasks to pick up. Some of these are located in appropriate places (though one would wonder how people could leave them behind), while some others are in unbelievable places, such as next to a cliff. There are also stacks of (seemingly unbranded) beer cans, though the player has to shoot these to be considered as having “collected” them. These two types of collectibles are quite silly.

WRITING:

Perhaps it would be ironic that reviews of Alan Wake would be critiquing its writing when it contains critique on writing itself. A particularly observant player may have this amusing notion.

Anyway, the relatively short prologue would show that the game has a presentation that resembles episodes of a drama thriller. Each chapter ends with a cliffhanger, usually involving a plot twist.

However, this plot twist is resolved rather quickly, but usually with the deposition of more questions to answer about the plot. More importantly, this quick resolution provides an excuse for the game to go back to being a game instead of a drama thriller.

The transition can seem very odd to people who are not familiar with both video games and serial shows. It is not a blend that would please everyone, but perhaps Remedy deserves a bit of kudos for trying to do what is not always done in video games (especially if one considers that there had been quite a few games that try to be blockbuster movies at the same time).

There are plot-holes in the story, and the game’s writers and even level designers are aware of these. The biggest of these concerns how a geriatric could manage the upkeep of a certain facility and hide supplies around the countryside and town of Bright Falls, even if the old person had decades to do that. A few characters would indirectly hint at being aware of such impossibility, but the plot-hole never was fully addressed.

This could be homage to a certain story-telling trope of old people performing feats that they could not possibly have done of course.

Continuing a certain tradition from the Max Payne titles that Remedy has once worked on, it has included some TV shows that the player can watch by having Wake turn on some old TV sets (if they are not turning on by themselves). One of these TV shows is Night Springs, which is a cheesy show that parodies The Twilight Zone.

The sound assets for these TV shows are created not by Remedy Studios, but other creators such as CSS Studios, a.k.a. Todd Soundelux. These other creators have designed the music, sounds, and voice casting for the Night Springs TV shows and the other live-action videos that are seen in the game.

There are also other live-action cutscenes that are played out on TVs, such as the living person that is the model for Alan Wake playing out certain scenes with story-related significance that would only become apparent late into the game. Even Sam Lake himself has a cameo in which he makes an amusing reference to the first Max Payne (for which he was the model for the protagonist).

Considering that most of the game is presented through visual content that had been designed by Remedy and that this is certainly not live-action, the TV shows might contrast too greatly with the rest of the game.

From the developer commentaries, Remedy’s designers have mentioned that the daytime levels were intended to provide breaks from the suspense and excitement of levels that are set in the night. The contrast is indeed visible, and there may also be some amusement to be had from how the story cooks up an excuse to fast-forward day-time to night.

Most of the characters other than Alan Wake are secondary characters, with seemingly no significance other than being part of Alan Wake’s travails.

There are some notable secondary characters though, such as Barry Wheeler, who is Alan Wake’s agent, publisher and best friend. There are also hints that Barry is actually Wake’s number-one fan. Any impressions that the player has about Barry also happen to be inverted in the DLC.

Speaking of the DLC, they happen to tie up a few things about some particularly enigmatic characters and Alan’s own hand in some of the events that happen in the game.

DLC:

The PC version of Alan Wake has the DLC packages, or “Special Features”, to use Remedy’s own words, packaged in at no extra cost. This is just as well, as most of the gameplay and content seen in the DLC are recycled versions of the one seen in the original package.

However, the DLC has stark differences in themes and presentation. Gameplay-wise, there are also some new interesting elements.

Some characters that appear in the DLC make references to the gameplay in the original build of Alan Wake, which can be amusing. For example, early on in “The Signal”, a pivotal character makes a remark about the gameplay significance of guns in the game.

There are more appearances of Barry Wheeler in the “The Signal” DLC. Specifically, the player gets to meet Alan’s own version of Barry in his mind. This is not necessarily for the better, because Barry is even snarkier and talkative in this chapter of Alan Wake’s story. On the other hand, for players that favoured Barry as a character, they may be pleased. There is also perhaps a critique against television-based media in the DLC, which is perhaps a tongue-in-cheek reference to the criticisms levelled against the game’s TV-show-like presentation.

Much of the gameplay in the DLC has been recycled; these include what Alan needs to do to banish the Taken and the Poltergeists. However, there is a new gameplay element of ‘willing’ things into “existence” by illuminating Dark-imbued words. Considering the surreal settings of the DLC, there is no need to justify this.

However, there is a serious problem with bringing supplies into existence. Instead of appearing on the ground, they drop from the sky, and then roll and bounce all over the place. More often than not, they fall very close to holes and chasms, and more than a few of them would drop into nothingness if the player is not quick enough to have Alan grab them.

The item that is most vulnerable to such wonky physics are the new models for the batteries. Since the deal with Energizer has lapsed by the time of the DLC, Remedy has implemented a new battery model that pays tribute to their development partners, Volt and Excell. The result is a long package of batteries with no inherent physical stability in its model.

The DLC chapters also happen to unwittingly expose the limitations of the Taken’s pathfinding A.I., especially that of the sickle-wielding one. Due to the crazy layout of the locales seen in the DLC, they are more than likely to just walk off edges and fall into oblivion. Speaking of which, there are more environmental hazards to worry about.

(Tiago Rocha and Tommi Saalasti are the designers responsible for coming up with the gameplay in both DLC chapters.)

The inconsequential collectibles have turned into alarm clocks in the “The Signal” DLC and Night Spring video game packages in “The Writer”. There may be something that is inferred by these, but if there is such a thing, it is very subtle.

PRODUCT PLACEMENT:

People who despise product placement in games, such as this reviewer, would have quite an issue with the in-game advertising in Alan Wake. The game developers have publicly mentioned that they try to be as conservative as possible with the advertisement, but these are of course just words on their part.

That a certain flashlight and most of the batteries in the game are Energizer products has been mentioned earlier. Another obnoxious example is Verizon’s presence on any telecommunications devices that are seen in the game.

Microsoft itself also inserted its own advertisement, appearing on computer screens in the game and any electronic device that could possibly support Microsoft software. The most obnoxious of these are the presence of Microsoft Tag bar codes for promotional stuff.

There are others that are less overt (and thus more in line with Remedy’s promises), such as the presence of Ford and Lincoln automobiles.

Most obnoxious of all, if the player lowers the graphical settings, the brand names still happen to be quite legible. The product placements also tend to be worked into pre-rendered cutscenes.

Unfortunately, the product placements continue into the two segments of the game that was once DLC on the Xbox 360 platform, such as that for Verizon.

If there is any silver lining from the product placements, it is that Remedy still owned the rights to the game and had attempted to compensate. It had placed the game in pay-as-you-like package deals, for example.

GRAPHICS – ANIMATIONS:

Most of the animations for characters that are seen in the game are made possible through motion capture, for which Remedy has worked with an astounding number of contractors (from looking at the credits) to produce.

The results of this collaboration can be seen in the animations for Alan Wake himself. There are specific animations for just about anything he does, such as different animations for climbing stairs and going down them. There are also a lot of context-sensitive animations, such as Alan vaulting up onto a rock when a player has him “jumping” in front of one.

An observant player might notice the amount of effort that has gone into making sure that Alan Wake moves like a real human would. However, the same player may also notice that his animations are also used by other (still-) human characters, such as the companions that follow him in some scenarios.

The Taken have their own sets of animations, one for each archetype. They look quite convincing at using primitive weapons. Eventually though, this appeal diminishes away when the player becomes apathetic to them and only regard them when trying to predict what they would do next. (One of the cheesiest animations is the raging roar that brutish Taken make before they do a barrelling charge.)

Poltergeists that inhabit inanimate objects impart very unsettling animations unto them. Possessed objects shudder with increasing violence as they “charge” up for a mighty hurl. This effect is particularly pronounced on very large objects, such as a bus.

The most unsettling example of animations for the poltergeists is that seen from a certain “reward” for a player that is curious enough to have Wake wandering about obviously spooky places instead of heading towards the light. In this scenario, the poltergeists possess something that is not exactly man-made; the resulting sight is certainly very different from the usual norm of scrap metal and wooden debris hurtling towards Alan.

GRAPHICS – BLURRING:

There is some application of motion blur as the player has Alan moving about. Fortunately, where visual clarity matters, the blurring is reduced to subtle levels. However, in other scenarios, such as when Alan has a hang-over, the blurring is particularly – and appropriately – significant.

There are many trees to be seen in the game. Most of them would eventually appear to have similar shapes due to being recycled for many outdoors levels, but it would be difficult for any player to become jaded to the effect that the Dark has on them.

When the Dark infests a section of forest, the outlines of the trees are blurred in unsettling manners while harsh winds have them swaying violently. All that blurring and motion, as well as severely limited draw distance, also happen to hide the appearance of the Taken, which can appear startlingly close to Alan.

GRAPHICS – CAMERA PANNING:

Camera panning is nothing new in games, but in Alan Wake, it is especially important because it is a crutch for lack of awareness on the player’s part and a tool of immersion.

Camera panning usually occurs only in cutscenes, but in less tense scenarios in which Alan is not in immediate danger, the player can relinquish control of Alan for a while to have the camera pan out and focus on scenes of interest.

As mentioned earlier, the Taken can practically appear out of thin air. Some of them announce their presence with garbled statements, but others are a lot quieter. In fact, in dangerous places such as the aforementioned Dark-infested forests, the Taken can spawn in considerable numbers and converge on the player, the howling winds having drowned out their approach.

This is when the camera would pan out, taking up an automatically calculated position that shows a more-or-less clear view of the encroaching Taken. If the player looks closely enough, Alan can be seen looking over his shoulder too. This may seem like a gameplay crutch, but it is nonetheless convenient.

GRAPHICS – LIGHTING:

Being a game with a lot of emphasis on the thematic contrasts between light and dark, it is fittingly appropriate that the best aspects of the game’s graphics are its lighting and shadowing.

The bright but soothing light from lamp-posts is easy to appreciate. Interestingly, the darkness is stilled when Alan stands under a lamp-post, and any pursuing Taken also happens to fade out of existence rather smoothly when Alan comes under one.

The Taken are all shadowy and such, but the game makes it easier to notice them when they are far away by surrounding their models with a dimly illuminated miasma. This makes them stand out from the surroundings, which is certainly convenient when there are so many levels with visual obstructions.

Speaking of shadows, they appear to take a backseat to the lighting (or lack of it) in the game. The starkest shadows that the player would see are those of trees, which make the forested sections of the game fittingly gloomy and ominous. Moreover, when the shadows disappear in order to make way for the cloying darkness, the player would know that trouble is afoot.

As mentioned earlier – and many times in the loading screens in the game – the player is to seek out faraway light sources if he/she does not know where to go. Perhaps in a rare touch of brilliance in the level designs, these light sources can be seen from anywhere in the open, if the mini-map indicator is not enough to guide the player.

GRAPHICS – OTHER MENTIONS:

There may be some issues with how the game spawns the Taken. When the game is at its best at doing this, they appear out of smoky barriers, giving them an otherworldly impression. At most times though, the game spawns them in locations that are usually out of sight of the player.

However, if the player happens to be orienting the camera in ways that the game designer does not expect or have Alan walking sideways or backwards into zones that trigger their spawning, they can seem to have been simply popped into place.

The health meter for Alan is partitioned into several arcs of equal length. The last two partitions are important, because they denote when there would be considerable changes to Alan’s motions and the colours of the screen. The other partitions, though, do not have clear significance. They may suggest that the game was intended to have gameplay elements that increase the length of Wake’s health meter.

VOICE-OVERS:

Alan Wake doesn’t exactly have a cast that would seem star-studded in the present day, but there are many veteran voice actors and actresses that have had experience in TV series in the past decade.

One of the most prominent among them is Matthew Poretta, whose last stint in TV series was in 2007 (according to cursory research on IMDb). He voices Alan Wake.

Initially, he may not seem to be the best of choices. Alan Wake sometimes sounds bland when he is narrating, though it can be argued that the impression that he is reading off a manuscript is deliberate. Fortunately, when more emotion is needed, such as when Alan Wake goes on one of his mercurial fits, Poretta delivers. The best of his performances are seen in Wake’s less-than-sane ravings.

Then there is Alice, voiced by Brett Madden. She delivers the impression of Wake’s troubled marriage very well. The contrast between the loving wife and an estranged one is particularly entertaining. (Of course, things are not as they seem, but to elaborate more would be to include a spoiler.)

Arguably, the most amusing – or infuriating - voice-over would belong to Barry Wheeler, who is voiced by Fred Berman. Perhaps this is because his character contrasts starkly with that of Alan’s, who confronts the Dark in a stoic manner while Barry shields his sanity with his affable sense of humor and perpetual excitement.

On the other hand, Barry’s chirpy personality can easily fray the nerves of people who despise incorrigibly upbeat characters.

The other characters in the story have comparatively short screen-time compared to these three. This is perhaps just as well, because some of them sounds bland, such as the sheriff of Bright Falls. (They also happen to have little in the way of character development.)

Nevertheless, there are some that stands out, such as the aforementioned geriatric that can seemingly do things that old people are not expected to be able to do. This old person says a lot of disturbing things about the Dark, but does so with a tone that is typical of a countryside grandmother.

SOUND EFFECTS:

Most of the sound effects in the game have been designed to make the Taken and other minions of the Dark sound as disturbing as possible while still making them humanly familiar.

As mentioned earlier, the Taken generally does not make a sound, unless they have been scripted to make their warped utterances. The player will need to listen to the rustle of leaves and footsteps other than Wake’s when moving through densely forested areas, if the player prefers to discover them before the camera does so for the player (as described earlier).

The howling of poltergeists becomes stronger as they shudder more violently. This is handy if the player cannot keep an eye on them, though this technique is not so effective when there are many of them. Still, the cacophony of many poltergeists howling their rage is entertainingly troubling in itself.

Any troubling noises that the player hears are silenced when the player gets Wake under a reliably working lamp-post, which strengthens the theme of the contrast between soothing light and the oppressive dark. However, the player may eventually learn the hard way that the sounds of light bulbs cracking mean big trouble is coming in Alan’s direction.

AURAL AMBIENCE:

There are plenty of noises that have been designed to make the night seem as ominous as possible. Although the player would be hearing little if any noises that are associated with nocturnal animals, the player will be hearing unearthly howls, snarls and illegible whispers. These noises are especially pervasive in Dark-infested forests, which make these segments all the more unnerving.

The DLC, in particular, uses these noises to the point of saturation, though not without a good reason; this happens to be in its settings. The experience would have the player quite jaded towards unearthly noises by the end of these chapters, but fortunately, the experience is quite short.

All that ambience for night-time incursions contrasts greatly with the relative silence of Dark-free day-time levels. Outside of pre-rendered cutscenes and scenarios that are more about story exposition, there is almost nothing to be heard when Alan is driving up and down the country-crossing roads around Bright Falls. This is perhaps to be expected because Bright Falls is a remote area, but the stillness of day-time may seem to be quite unbelievable (if the player could not write it off as a deliberate attempt to contrast against the night).

MUSIC:

The music in Alan Wake is licensed, hence its TV show appeal. Still, the composer for the game, Petri Alanko, deserves credit for picking licensed music that is quite appropriate for the presentation of the game.

Two of the most notable soundtracks have been performed by real-world band Poets of the Fall, but they are amusingly credited as the “Old Gods of Asgard”, characters that happen to appear in the story. These two soundtracks have lyrics that may seem silly, even to people that have played the game and know its significance. Yet, these two tracks have very memorable tunes, especially when they are used to end certain important episodes with.

CONCLUSION:

Alan Wake may have a few proverbial pitfalls in its gameplay, such as combat encounters that are reused for one too many times, and obnoxious product placements, but these should not be enough to prevent Alan Wake from being a surprisingly good offering from Remedy Entertainment.