INTRO:

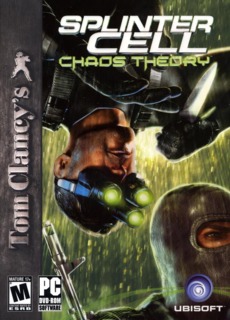

Considering the reception of the previous Splinter Cell games, it was not a surprise that there would be another to propagate the franchise, and for Ubisoft to reap the rewards from (through ways that can be considered dubious, at best).

However, the premise of the game may seem all too familiar to those who had been following the series; Sam Fisher and colleagues would be investigating and eliminating yet another threat to the United States of America, uncovering yet more unlikely enemies along the way. In fact, the premise may cast a shadow over the improvements in gameplay for the single-player mode, which is after all driven more by story than game mechanisms.

Of course, if a player can look past the idiosyncrasies of the story, he/she may notice that this entry in the franchise has built on what was well-received in the previous games, and removed others that were not so. Unfortunately, the player may also notice some other things that are not as pleasant and which give hints on Ubisoft's plans for the franchise.

PREMISE & COMMENTS ON SINGLE-PLAYER STORY:

The previous games had dealt with biological weaponry and nukes, so perhaps it is expected that the story in Chaos Theory would concern itself with other kinds of weapons of mass destruction. However, perhaps slightly surprisingly, the weapon of terror in this game is of the digital sort. To elaborate further would be to invite spoilers, but it should suffice to say that it is yet another weapon has fallen into the wrong hands, and it is Third Echelon's job to wrench it away from the hands of those that would use it against the United States and its allies.

The person that would do most of the field work that matters would again be Sam Fisher, who is still reluctantly aging. It can be said that the story's best humor lies in how Sam and his colleagues banter about his advancing age and his resentment at being considered old. However, the more serious of players may consider that this is playing the theme of growing old, which had been in the previous games, too much; Sam's remarks about diapers can seem jarring to some, for example.

However, there are some unexpected twists and turns in the story that would be refreshing to most players. These would not be elaborated beyond the statements that they involve the themes of betrayal brought about by the bitterness and resentment of those who had been expecting more gratitude from those that they have served for a long time.

On the other hand, people who are expecting a more empathetic response from Sam Fisher to these twists and turns would be a bit disappointed; he remains a stoically decisive person. Of course, others would prefer that he remains emotionally strong.

(As a side-note, it is worth noting here that Sam Fisher's personality in this game is remarkably different from that in the Splinter Cell games that would come later.)

COMMENTS ON CO-OP STORY:

However, the overall story of Chaos Theory is not just limited to the single-player mode. There is a co-op campaign mode, which concerns two other Third Echelon agents that are involved in missions that Sam Fisher is not personally undertaking. Their story involves handling loose ends in Sam Fisher's investigations, as well as some other secondary plot branches.

In fact, only some moments of their story are intertwined with that of Sam Fisher's in Chaos Theory. Of course, this is perhaps still well in line with the game designers' vision of their story being a behind-the-scenes complement to Sam Fisher's own.

It has to be noted here that they have not been canonically named, but their contribution to the canon of Splinter Cell is not entirely worthless as a consequence. The development of the story in the co-op campaign has themes of official secrecy, which is portrayed through their lack of knowledge about the identities and statuses of other Third Echelon agents, and which in turn raises issues of trust. However, the story in the co-op campaign would not exploit this to dramatic effect, for better or worse.

TUTORIAL – EXISTING GAME FEATURES:

The gameplay fundamentals of Chaos Theory's story-related modes would be quite familiar to veterans of the previous game; the player takes control of a Third Echelon agent and is tasked to sneak around locales that are guarded by characters that do not take kindly to unexpected visitors, in order to reach an objective.

The first mission in Sam Fisher's story campaign acts as a tutorial for these fundamentals, starting with basic things like moving around; he is inserted into a quiet and unpatrolled region of the mission area for this purpose, conveniently enough. For the veterans of the previous games, the controls would appear mostly unchanged for the controlling of Sam Fisher, as are the fundamentals of sneaking behind enemies and nabbing them, or around them by making use of visual obstructions and dark shadows.

TUTORIAL – BACKGROUND NOISE FEATURE:

The tutorial does feature a gameplay feature that is new to the series: background noise. The first mission in Sam Fisher's campaign is set against a storm, which certainly provided a heck lot of background noise to hide the player character's movement with. To help track this, a new meter has been added under the meter for illumination; an icon shows the threshold of how noisy that the player character's actions has to be before they can be heard by A.I.-controlled characters above the ambient noise, even when Sam Fisher is right next to them.

This helps stealth-favouring players get through a mission without causing a ruckus, which is considered by some as a particularly praise-worthy achievement.

TUTORIAL – MISSING FEATURES:

The tutorials also highlight some changes in the game through the absence of certain things that have been seen in the previous game. Most of these concern scripted movement maneuvers that had been in previous titles.

A change that would be welcomed by most players is the removal of certain unbelievable maneuvers that were in Pandora Tomorrow. The most dubiously prominent of these is the SWAT maneuver, which somehow allowed Sam Fisher to pass under the sight of enemies when he moves along and across doorways, even when they are looking directly through these.

Another change that would perhaps be missed more is certain acrobatic moves that are also scripted, namely a certain kind of jumping animation that the player character uses to jump up onto platforms above a narrow passage.

GAMEPLAY – GADGETS & TOOLS:

The previous Splinter Cell games provided Sam Fisher with gadgets that were useful in handling the opposition during missions. Chaos Theory builds on this design policy by adding some new gadgets, most of which are useful. As for the existing ones, they have been mostly retained. For example, most of the non-lethal ammunition for the SC-20K rifle such as the Sticky Shocker have been retained and function as expected.

The Sticky Camera, however, has been improved. It has now been combined with the Diversion Camera of the previous game, which makes it even more useful. The Camera can still be used to look around and make noises even after its gas payload has been expended (assuming that it has not been damaged by enemies that have discovered it), which is convenient. Moreover, the Sticky Camera still can knock out enemies that have been hit in the head with it, amusingly enough.

One of the new gadgets is particularly noteworthy as it made an existing weapon even more useful and versatile than it was in previous games. This is the OCP device on Sam Fisher's sidearm, which can be pointed at electronic devices to disable them for 15 (very long) seconds. Sometimes, it would be more prudent to knock out a device for a while instead of shooting it outright.

Moreover, the disabling of electronic devices and lamps count as minor disturbances, thus not spooking enemies enough so as to cause them to move around too much during those 15 seconds. Furthermore, in Chaos Theory, there are electronic devices and lamps that are armored against gunfire, thus making this tool quite indispensable during these moments.

The EEV device is similar to the OCP, as it is also a gadget that has been attached onto an existing device, which in its case is the pair of binoculars that Sam Fisher has. It can be best described as a remote hacking tool, which helps to hack into electronic devices from a distance away; in previous games, they can only be hacked up close. This can be very, very handy when there are enemies nearby keeping an eye on the device. The EEV is also used for some story-centric moments, such as lip-reading and scanning containers from afar.

Hacking will be described later.

The high-tech goggles that Third Echelon agents use have been upgraded with a new viewing option, the Electromagnetic Field (EMF) mode. This allows for the detection of electronic and electrical devices, but visually obliterates just about everything else in the environment. Anyway, this mode is stacked on top of the other modes, which returns from the previous games, such as seeing laser beams with the night vision mode.

A particular tool that is available to the player in Chaos Theory is remarkable, not because of its sophistication, but because it was not in the previous games despite being rather practical to someone such as the Third Echelon agent. This is the knife, which was not featured much in previous games, for whatever reason.

In addition to being used to cut up unsuspecting foes with, the knife is also used to cut through certain soft obstacles, such as tarpaulins, so that the player character can step through them. It can also be used for stealthy kills from behind, of course.

Hand grenades are also available to the Third Echelon spy, and may even be obtained from certain locations in levels, such as armouries. Grenades come in three varieties: the explosively loud frag grenade, the blinding flashbang and the cover-providing smoke grenade.

Overall, hand grenades would be quite difficult to utilize. A.I.-controlled enemies always run from frag grenades that they manage to see coming, whereas flashbangs do not hold stunned enemies in place for too long; in fact, it may be more prudent to throw flashbangs ahead of frag grenades, if only to hold enemies in place for the blast. Smoke grenades last somewhat longer and are useful for moving through well-lit places, but the smoke is more than likely to spook enemies into high alertness (though not enough to sound an alarm).

GAMEPLAY – GUNPLAY:

Shooting and shoot-outs in general are still viable solutions to problems, so it is fortunate that Chaos Theory has gunplay as competent as that in its predecessors. Some new additions to the arsenal also improve its sophistication.

Perhaps the most pleasing design in the gunplay of Chaos Theory is that Sam Fisher can now switch between holding his gun left-handed and right-handed, or more precisely, he is now ambidextrous. This change is not explained in the canon, but gameplay-wise, it is a convenient one.

Considering that the positioning of the camera when Sam Fisher aims his guns has not changed much since the previous games, switching from right-handed to left-handed and vice versa is helpful when aiming around corners. This is useful for both lethal and non-lethal purposes.

The SC-20K gun now has an alternative attachment that turns it into a combo of an assault rifle and shotgun. With this attachment, the control input that is originally used for launching gadgets from the SC-20K is used for firing the shotgun instead. This fills in a tactical gap in the player's arsenal, namely the need for a close-quarters firearm.

The shotgun attachment may not please players who insist on Splinter Cell games having more emphasis on stealth, but players who prefer to have more options to resolve problems – even through violence – would be satisfied.

Other than this, the SC-20K rifle is not exactly the most reliable of guns to use in a fight. Without the foregrip or shotgun attachment, the player is stuck with a weapon with plenty of recoil, not unlike how it was in previous games. As for using it for sniping with the sniper attachment, it still has a lot of wobbling, though the player can have Sam holding his breath to still the crosshairs.

However, it has to be mentioned here that equipping any other attachments other than the launcher attachment deprives the player of very useful gadgets, namely the special ammunition that the attachment fires.

GAMEPLAY – HACKING MINIGAME:

Hacking is not an automatic affair, as in previous games. When the player hacks into something, a special user interface is presented on-screen in real-time, much like that for unlocking doors in previous games.

A bunch of numbers appears on the user interface, looking very much like a scramble of numbers. To progress, the player needs to observe the changing numbers for when a particular number is highlighted. Selecting this highlighted number locks them in place, completing part of the sequence of the numerical sequence needed to hack the device. Having the right sequence of numbers has the player successfully hacking into the electronic device.

However, selecting the wrong number reduces the number of opportunities that the player has left to secure another number. This is an understandable penalty, but the game also penalizes the player for aborting the hacking process; this also reduces the number of tries left, which can be difficult to stomach.

Having the number of tries dwindle down to zero automatically triggers an alarm and locks the device from further hacking, unless it is a critical device that must be hacked.

More importantly, the hacking process must be successfully completed in a set amount of time, or else an alarm will be raised anyway.

This mini-game can seem difficult to learn, due to lack of in-game tutorials and comprehensive documentation on this mini-game. The player can rely on third-party tutorials of course, but this does not change the fact that the game itself does not have enough in-game learning aids.

After a successful hacking, he/she can perform actions that are associated with said device, such as looking into messages and downloading databases when a computer is the device being hacked.

However, not every electronic device is defenceless against the EEV. Almost all of them have defensive measures in the form of scanning scripts that will detect the digital presence of the EEV after some time, which is depicted via a timer that will countdown to zero. If the player is discovered, the alarm will sound and there would be enemies advancing towards the location of the player character.

The player can choose to exit hacking before time runs out, but the numbers will reset themselves, thus preventing the player from exploiting the system in cheesy ways. For electronic systems that are not critical to the completion of primary objectives, the player only has a limited number of hacking attempts before the device is locked out altogether, which is an occurrence that also raises the alarm.

If there is a major complaint with this hacking minigame, it is that the user interface for it is even more intrusive than that for the lock-picking minigame; it covers almost the entire screen.

GAMEPLAY – HOLDING ENEMIES HOSTAGE:

In the previous game, the player character is not able to hold someone else hostage and move forward; the player can only have both characters walking backwards and making slow turns, which make holding enemies hostage during combat quite unfeasible.

In Chaos Theory, the player can now have both characters moving forward. This may seem a small change, but it does now allow hostages to be used as meat-shields.

As for the disposal of hostages, the player has the option of killing enemies outright or knocking them out. The results are always consistent, but the animations for either option can vary between a few sets of animations.

For example, lethal options often involve neck-snapping or an awful knee to the spine, whereas non-lethal options may involve pistol-whipping the hostage, choking them unconscious or punching them hard in the temple. Some animations are even context-sensitive, such as Fisher sending a hapless person over a railing that is looking over a particularly long drop.

It is worth noting that if the player took lethal options, Fisher does not use the knife. It may be a practical consideration as enemies would theoretically bleed and leave clues to his passing, but this consideration is not applied for when Sam Fisher stabs enemies from behind without taking them hostage.

The durations for the animations appear to be comparable, so there is no apparent gameplay consequence beyond the importance of having a hostage killed or knocked out.

Of course, if the player is playing story-related modes, he/she may want to interrogate enemies in order to obtain the necessary information to move forward in a mission. This still acts out much like it had in previous games, e.g. the player presses buttons to have the player character (generally this would be Sam himself) force some discomfort upon the hostage in order to loosen their tongues. There has not been any remarkable change in the gameplay here.

ENVIRONMENT DESIGNS & MAP SCREENS:

In previous Splinter Cell games, the player only has access to 2D maps, one for each floor of a level, if it is multi-storeyed. At best, the map screen in the user interface only helps to give the player a sense of general direction.

In Chaos Theory, the player can bring up 3D maps of the level being played, which can be panned and rotated around to help the player get his/her bearings. They are a lot more complicated than 2D maps, but if the player wishes for more simple representation of the level, he/she can still opt for a top-down view.

However, this does not mean that levels in Chaos Theory are designed in a manner that is very different from those in previous games. Levels in Chaos Theory are still practically a string of discrete sections that are separated from each other with corridors and vertical shafts (either ladders or elevator rides) that hide loading times; vents that the player character has to crawl through are also used for the same purpose.

In other words, what happens in one section, no matter how explosively loud it is, will not be bringing enemies from other sections of a level over to investigate, as long as the player character has not moved into a region where adjacent sections would be loaded (together with its NPCs).

The rather linear and sometimes claustrophobic level designs also somewhat diminish the thematic appeal of the maps, which are supposedly based on locations around the world. If not for details like foliage, tatami mats and bamboo, the levels would seem to be little more than rooms that are connected with corridors and ventilation shafts, interspersed with nooks and crannies for hiding.

Yet, this is not to say that there have not been improvements in environment designs. Perhaps the most notable improvement is the introduction of light sources that are not powered by electricity. Some of them are fuelled by oils and solid fuels, and there is little that the player can do about these other than to destroy them, if he/she can. Examples of these include fireplaces and campfires. Light sources that are protected against gunfire are also a noteworthy addition to the game.

ENEMY A.I. DESIGNS:

In the story-related game modes of the previous Splinter Cell games, the A.I.-controlled enemies that oppose the player(s) generally outgun the player character(s), but are not exactly very smart in dealing with individuals who meld into shadows easily and who are generally a lot faster and nimbler. Thus, a wily player can easily outmaneuver them and pick them off one by one, after having observed their patrol routes or sentry positions. He/She can even lure them into ambushes and gun them down as they come around corners, if he/she has a quick trigger-finger and makes timely reloads.

In Pandora Tomorrow, the player can create small commotions, like breaking bottles or throwing rocks, and enemies would come over to investigate, thus making for very convenient diversions.

In Chaos Theory, most enemies are more conservative and are less willing to go on a chase if the commotion is minor. Some would not even leave their guard posts to investigate such disturbances, especially those that are looking over sensitive areas. Those that do leave their posts give up quicker and then return to their posts, thus providing smaller windows of opportunity for bypassing them after having used minor commotions.

Only a significant non-lethal commotion, like objects in the environment being deliberately shot at or one of them being hit with something harmless thrown at them from the darkness, would have them looking around with more fervour. However, unless one of them has been incapacitated and/or they have confirmed the presence of the player character, they will eventually return to a state of general alertness.

Of course, actually inflicting harm on them, either lethal or non-lethal, would send them into an angry flurry and combat would ensue, if the player could not get rid of nearby enemies with just a single action.

A.I.-controlled enemies are also much warier of the darkness now. As in the previous games, they will not go into the darkness without some light. However, in Chaos Theory, they may not even investigate dark areas at all, especially if they are only on sentry duty and not on patrols. Only the confirmed presence of the player character would get them to move with more urgency through dark places, and even then they are a lot harder to surprise as they are already quite alarmed.

Although enemies are noticeably more conservative now, they appear to become suspicious by many more things; ajar doors, missing items (with the exception of miscellaneous objects like bottles) and computers being turned off when they were turned on before will tip them off that something odd is going on. On the other hand, minor disturbances will not hold their attention for long, so such changes are probably only included so as to make enemies appear more authentic (though this is still a commendable game design).

All of the above A.I. designs are then further altered by the difficulty settings. In addition to influencing the usual durability/damage-output ratios that enemies have, difficulty settings alter the behaviour of enemies. They do not change the fundamentals of their behaviour, e.g. enemies will still investigate disturbances, but their attention spans have been changed.

For example, at higher difficulties, they appear to virtually ignore minor disturbances, making actions like throwing bottles and miscellaneous objects against walls and floors much less useful.

Such difficulty designs may seem to pose a greater challenge to some players, but for some other players, they may seem to have reduced their options for getting past enemies.

NPC DESIGNS – KNOCKED-OUT NPCS:

The Splinter Cell games provide a lot of tools for the player to knock out NPCs with; Chaos Theory is no different. NPCs can be knocked out with gadgets and melee moves, but more primitive solutions also work: throwing hard objects at NPCs' heads and bashing a door into them as they come closer to a doorway have the same effect. Having Sam fall down onto someone from above is also a viable option, amusingly enough; there are more than a few levels where narrow but high corridors allow the player to have Sam balancing himself against the walls before dropping down onto an unsuspecting person that is passing under him.

It is also worth noting here that enemies that have detected Sam can be knocked out with a single blow, as opposed to the couple of blows that are needed in the previous game.

However, knocked-out NPCs do not necessarily stay knocked out; other NPCs that come across them may attempt to wake them up. If they successfully do so, not only an alarm will be raised, the player would also have to contend with an NPC that has been brought back to complicate the mission.

It appears that the method used to knock out NPCs with may influence the probability of other NPCs being able to revive them. If NPCs had been knocked out up-close, they tend to be out for the rest of the mission and cannot be roused. Enemies that are knocked out via other means may be infrequently revived.

Of course, if the player had hidden unconscious NPCs at somewhere that is secluded, then he/she may well not need to bother about this. However, certain missions impose a timer on the player such that he/she would be hard-pressed to hide all bodies properly.

BRIEFING, DE-BRIEFING & MISSION OBJECTIVES:

The previous Splinter Cell games allow the player to kit out Sam with the tools that he may need for a mission; Chaos Theory continues this tradition. There is now the option of making broad changes to his gear by selecting loadouts, which are named according to the approaches that the loadouts best facilitate. For example, the "Assault" loadout gives Sam the most ammunition, which is to the preference of players who want violence to be always a viable option.

During a mission in the story-related modes, the player is expected to achieve, at the very least, the primary objectives. In Sam Fisher's story mode, missions often have other objectives that are not as critical, but which can be achieved anyway for some minor rewards, such as exposition on the motives of secondary characters and some more substantial ones, like the removal of obstacles in the way to the primary objective.

Upon completion of a mission, the player will be given scores according to their performance in the level. How many civilians were spared, how many alarms raised and how many times that the player character has been exposed to the enemy are among some of the criteria used to grade the player's performance, so it should be apparent that raising too many commotions during missions is frowned upon by the game. The game also encourages non-lethal solutions to dealing with enemies, and the de-briefing screen will reflect the player's adherence to this accordingly.

Although the scoring screens would be handy for players who want to perform missions as stealthily as possible, they would be of little substantial consequence because there are no rewards to be had from scoring highly (other than self-satisfaction) or penalties to be had from raising hell.

CO-OP CAMPAIGN:

This game mode mostly shares the gameplay designs of Sam Fisher's single-player campaign mode, but has additional features, namely scripted context-sensitive actions that make use of the fact that there would be two player characters that have to work with each other.

The co-op campaign itself has a tutorial level, which helps players that are new to this mode to acclimate themselves to its requirements. As mentioned earlier, most of the gameplay designs in this mode are present in Sam Fisher's mode, such as the fundamentals of sneaking around while using gadgets to find one's way through a level. However, the tutorial mode also emphasizes the need for the two player characters to come together to overcome an obstacle.

This is perhaps the main appeal of this mode, as some obstacles can be more conveniently overcome with a co-op action than when the players attempt to work around them while being separated. Moreover, not being alone means that some amusing tactics that are not possible in Sam Fisher's mode can be used to overcome enemies, such as using one player as bait while the other plays the role of the ambusher.

However, sceptics can argue that the co-op mode may have shoe-horned the need for the players to stay close to each other. There is no immediately apparent means for one player to know where the other is; the means that are indeed immediately apparent are voice and text communications between the players, but these do not exactly provide visual aid.

This can be a problem if one of the player characters gets into trouble and becomes incapacitated. Death is not immediate for him, but the other has only around half a minute to get to his partner and revive him, which is easier said than done as enemies often linger around the incapacitated player character, who can do nothing much (though the player that was controlling him can still describe his surroundings).

If there is a major complaint about the co-op mode, it is that it does not have many missions. Perhaps this was deliberate in order to place more focus on Sam Fisher's story, but this also detracts attention away from what Chaos Theory is trying to do differently from its predecessors in terms of story campaign modes.

MERCS & SPIES:

This game mode returns from Pandora Tomorrow. At launch, the premise of this game mode was the same as that in the previous game; SHADOWNET, which is a unit under Third Echelon, has to go up against mercenaries from ARGUS again, in matches with objectives that are somewhat related to the events in Sam Fisher's campaign and the co-op campaign.

The Spies are still equipped with camouflage suits and their multiple-vision goggles, giving them an edge in stealth, or at least staying hidden from opponents. They still have mostly non-lethal firearms, though these, as in the previous game, can fire special ammunition that makes spying on the Mercenaries a bit easier, assuming that the latter is not aware of their usage. They also still have their plethora of grenades that can be used to stun or disorient the Mercenaries.

The improved Sticky Camera may seem to benefit the Spies though, though the ARGUS mercenaries do not stay knocked out permanently if they fall victim to the gas release.

As for the ARGUS mercenaries, little change has been effected unto them too. However, as in the previous game, they are still very effective against spies that have made mistakes in their approach to the objective, what with their lethal firearms and traps, such as their mines.

Perhaps the greatest change in this game mode over its predecessor in Pandora Tomorrow is the introduction of the "story" match type. In this match type, objectives do not appear to be rigid anymore. The Spies often enter matches with a series of objectives that have to be done in no given order, whereas the Mercenaries have to switch their focus to different areas of a level according to the Spies' progress.

SOUND DESIGNS – VOICE OVERS:

As mentioned earlier, there are bits of voice-overs in the game that can be entertaining, such as banter over Sam Fisher's advancing age. Otherwise, most of the voice-overs are for no-nonsense briefings and de-briefings, which can seem a bit dull but somewhat understandable. Their monotony is sometimes broken by Irving Lambert's outbursts when he has just obtained critical and unexpected information, which makes his character a bit more colourful, but this is quickly tempered down by Sam Fisher's and Grimsdottir's often-calm responses.

However, the implementation of the voice-overs may cause a bit of disbelief. One such case occurs when Sam Fisher is interrogating an NPC while both of them are well within earshot of other NPCs. Despite the loud grunts and groans that NPCs make when Sam Fisher causes them discomfort, the other NPCs would not be able to hear anything; they only disrupt the investigation if they spotted Fisher and his hostage. Such a design oversight detracts from the feature of noise management that was mentioned earlier.

The voice-overs for unimportant characters are delivered by multiple voice actors and actresses, at least for the English voice-overs, so they would not sound too recycled.

However, toggling to native languages would reveal that the roster of voice talents is far smaller, such that a character of Oriental background would sound like another character of Oriental background, for example. Moreover, there does not seem to be any subtitling for these non-English voice-overs. Moreover, NPCs that were previously talking in their native language would switch over to stereotypically-accented English when they are caught and interrogated, which can be a jarring transition.

SOUND DESIGNS – MUSIC & SOUND EFFECTS:

Amon Tobin designed the music for this game; the result sounds remarkably different from the music in the two previous games (which have different composers too). However, thematically, the musical track in Chaos Theory is the same; it projects the suspense of being a clandestine agent working against shadowy organizations in a pleasingly entertaining manner. The emphasis on electronic may be off-putting to those who prefer the occasional orchestra in previous games, but for those who are looking for a change, it would be welcome.

As in the previous games, the music changes tracks when the situation changes, which is a convenient aural cue that the player should start looking around for what's happening and for any opportunity to adapt.

If the music is not enough of an aural cue to alert the player to changing situations, then the sound effects are. During quiet times, the player will only hear background noise and the dialogue and monologue of NPCs. Any change in these usually means that something has changed and is worth investigating.

Of course, if other much more significant sound effects come into play, like gunshots and people shouting angrily, that's when the proverbial turd has hit the fan. The player would already know that most of the time, but there are some scenarios where commotions are not started by the player and are part of scripted events instead.

Appreciating the noisier and abrupt of sound effects would be difficult, as the game would remind the player that it is in his/her interest to keep a low profile. Even if the player deliberately creates a ruckus to check out these sound effects, he/she would find that they are not exactly very remarkable to listen to; firstly, the guns that the spies use are often suppressed and would not please those that prefer loud reports.

Gunfire from enemies does sound different, depending on the firearms that they are using; this goes some way to portray differences between different gun models, at least from an aesthetic point-of-view.

GRAPHICS – MODELS:

The characters in the game look believably human, but an observant player would eventually notice that many characters, namely the unimportant ones such as the goons that patrol maps, share the same model skeletons and animations, which will be described later. The major differences between them are their polygons and textures (and voice-overs), but little else.

The best models are of course reserved for the player characters, with Sam Fisher getting most of the best-looking ones in the game, from masked to unmasked versions and with different skin-suits. These have plenty of details and textures, especially on the computer version of Chaos Theory.

The mercenaries and spies in their namesake game mode are just as impressive as Sam Fisher, if only because they have plenty of gadgets on their person that make them look fearsome. Some of these are just there as props for their models though, though others have more importance to gameplay, such as grenades on Spies showing how many of such items that they have remaining.

The guns and gadgets in the game also have models that are worth noting, if only for their variety in models. Armed NPCs have a variety of firearms depending on the locale of the mission and the characters' backgrounds, but the differences between them are not immediately noticeable, especially if the player does not get into shoot-outs often.

In fact, if one gets into shootouts anyway just to see if there are any differences in enemies' firearms, he/she won't find many to be had; enemies of different backgrounds may have different competencies in shooting, but these can be attributed to the A.I. designs instead of their firearms. Therefore, the variety of firearm models in the game contributes more to the game's aesthetics than it does to the gameplay.

The best firearm models are of course those for Sam Fisher's. The SC-20K was a peculiar-looking weapon when it debuted; in Chaos Theory, it is even more outlandish, what with its shotgun attachment that firearms experts would consider quite astonishing (if they are polite about it and would give the game the benefit of the doubt).

GRAPHICS – TEXTURES AND DECALS:

Pools of blood are decals that appear when enemies are slain and left to bleed where they lie. As in previous games, pools of blood are not just there for aesthetic purposes.

They are still decals that have relevance to the gameplay, as enemies would become somewhat suspicious if they come across an unexpected puddle of red. However, if they could not locate any other clues within minutes, the pools of blood are eventually disregarded, which is perhaps unbelievable, though this may have been so for convenience of gameplay.

However, it has to be noted here that enemies that have been stabbed do not appear to bleed much; the player can still shift the bodies quickly enough to prevent blood decals from appearing where stabbed enemies fell.

Other decals include charring from explosions and pitting from the impacts of bullets. Enemies cannot notice these, but then what caused these would have alerted them so much to beyond caring that furniture had been blackened or that there are holes in walls.

For a 2005 game, Chaos Theory had very splendidly detailed textures. The most sophisticated textures are reserved for the player characters (and not just Sam Fisher). This is appropriate, as the player will be looking at them the most, what with this game mostly using a third-person camera (with the exception of the first-person camera used for the Mercenaries, at least by default).

GRAPHICS – ANIMATIONS:

The animations are perhaps the most impressive aspect of the graphics, as they are always visible regardless of the filter that is being used by the game.

Many of the animations in this game are motion-captured, which results in them being rather believable. One notable example is the animation for when the player character in either story mode pulls an enemy over a railing to a gravity-inflicted doom while hanging from underneath it. It is outrageous, but still somewhat believable.

The myriad ways of dealing with hostages have been mentioned earlier, though some of them are still worth noting again if only because of how astonishingly cruel they are, such as Sam Fisher sending a knee hard into the backbone of an enemy who has just been threatened with a neck-snapping or a knife to the throat.

Holding hostages also highlight the facial animations of the game, assuming that the player has oriented the camera around to show both of their faces. However, the highlighting is not necessarily for the better overall.

The hostage's face turns into a believable grimace when a player character takes him into a choke-hold, while the player character, if he is not masked, shows somewhat clear strain on having to exert strength for this action. Letting go of the controls for a while lets the player see some 'idle' animations, such as both characters breathing and the hostage occasionally testing his captor's hold, only to be reprimanded with a brief but discomforting tightening of the latter's grip.

However, eventually the player may notice that these animations are recycled for just about any hostage. They also happen to highlight the similarities in the models for characters, as have been mentioned earlier.

Speaking of recycling animations for hostage-holding, other animations are also recycled for many characters. For example, each patrolling guard that is armed with a rifle would move and walk about in the same way as the others. Of course, one can argue that this is to be expected of any professionally trained soldier, but it is difficult to deny that there is little difference in personality among soldiers of supposedly different backgrounds that is portrayed through their animations.

The best of animations in the game are reserved for Sam Fisher and the other Third Echelon spies. Their animations have plenty of nuances, such as a more careful gait in their creeping animations that sets in when they get closer to a would-be victim. This is in addition to the various acrobatic moves that are unique to only them.

One could argue that these animations are context-sensitive and could not be replicated anywhere in a level that does not have the necessary scripts, but it would be difficult to deny that they do not look impressively believable and even more difficult to claim that they would look out of place when they are performed in segments of levels with said context-sensitive scripts.

NPC characters that are under fire from player characters appears to grimace and flinch, which make their responses seem more authentic. They also display animations that are not available to player characters, such as hasty and graceless dives behind cover (as opposed to the player characters' more measured somersaults).

PRODUCT PLACEMENT:

Perhaps the least pleasing aspect of the graphics is the inclusion of product placements. Although some of the products shown in the game are fictional, many are associated with high-profile real-world brands. There are neon signs for AXE (a producer of grooming products for men), as well as actual in-game items for AXE products, and screensavers for NOKIA and AMD on in-game computer screens.

Of course, one can argue that the product placements that have just been mentioned are too out of the way to be noticeable, but it would be difficult to say the same of those in the cutscenes for the game. There is a cutscene that has Sam Fisher chewing Airwaves Gum, another one for the same brand reflected on a window, and another cutscene that has a packet of the gum sitting innocuously next to a radio.

MISCELLANEOUS COMPLAINTS:

There had been a disconcerting change in the presentation of Ubisoft games during this game's time, and which has prevailed to today. This is the inclusion of videos that play just after the game has just been started, and these videos typically display the logos of Ubisoft and others who contributed to the game's development. However, the video for Ubisoft's logo cannot be skipped at all, which can seem obnoxious to some. This self-advertising does not end there; there are more than a few in-game references and Easter eggs that feature Ubisoft's game-developing assets.

Despite the similarities in gameplay of the spy player characters, they have different default key bindings for controls in the computer version, which can lead to some initial frustration as the player rebinds keys or adapts to the different sets of bindings.

The multiplayer modes of the game require connections to Ubisoft's proprietary servers for match-finding, which imposes some annoying requirements. Unfortunately, time would show that Ubisoft had not learned from the complaints about these, and may well have gotten worse.

CONCLUSION:

If the gameplay designs of the two previous Splinter Cell games can be considered to be the formula of the series thus far, then Chaos Theory can be considered as the culmination of the development of the formula, what with new tools and techniques that are available to Sam Fisher and the removal of some dubious ones. The inclusion of a co-op campaign also filled in a gap in the multiplayer offerings of the franchise at the time of this game, though it is quite short. The computer version of the game also featured splendid graphics as was the tradition of the computer versions of the Splinter Cell games, at least up to Chaos Theory.

However, Chaos Theory also showed some disconcerting signs about Ubisoft's visions for its products, namely having noticeable product placements and a lot of self-advertising in its games. This would come to happen as well as somewhat pass, but this game may well have marked Ubisoft's foray into dubious product design policies.