INTRO:

Arcen Games has demonstrated its eagerness to make very complex games with “emergent gameplay”, a buzzword which Arcen delivers quite well with A.I. War. However, having made Tidalis, one would wonder whether Arcen’s eagerness had backfired on it.

Tidalis is fundamentally a match-three puzzle game. However, its complexity is far, far greater than just any known casual match-three game, such as Bejeweled. This is not exactly for the betterment of the game however, because instead of being an enjoyable waste of time, Tidalis can be frustratingly unpredictable.

PREMISE:

It is rare that a casual match-three game (if Tidalis can be considered one) actually has a story, but Arcen’s title certainly has one; someone at Arcen apparently insists that each of Arcen’s games has a premise.

However, Tidalis’s story-writer is quite forthright in saying that the story should not be taken seriously. It is quite difficult to rationalize the need to solve match-three puzzles and include it in a coherent story, so Tidalis’s story simply has the levels appearing in it as a deliberately whimsical and bizarre plot element.

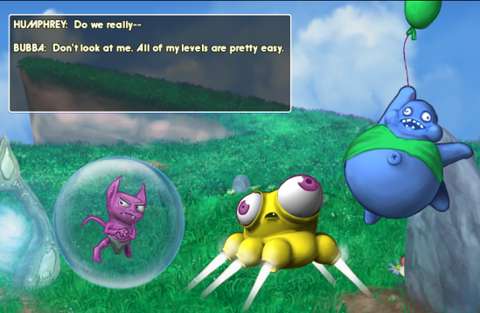

Unfortunately, Arcen’s designers might have taken the whimsy for granted, creating characters and plots which have shallow entertainment value. Their looks might be worth a few short laughs or amused smirks, but they are far from memorable.

Anyway, the player character is ostensibly a human from some fictitious world which is seemingly in an epoch equivalent to the real-world Imperial age. He/She (it is not always clear which gender the player character is) has been stranded on the titular island of Tidalis, following a shipwreck. The island is populated by bizarre-looking but otherwise sentient creatures, all of whom consider the player character to be very strange-looking and tactlessly refers to him/her as “it” and “the alien”.

For whatever reason (if it can be considered “reason”), the inhabitants of the island has a predilection with puzzles and initiate conflicts with each other by placing puzzles in each other’s way. They are apparently compelled to solve these puzzles.

There are a lot more inanities in the story than just these, as will be described later, but as the story-writer has mentioned already, it is too whimsical to take seriously.

TUTORIALS:

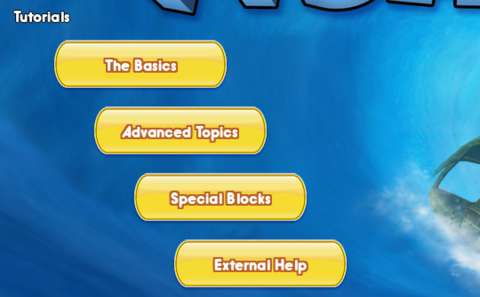

Arcen Games has a habit of making sure that there are enough tutorials and documentation to explain away the complex designs in its games. Fortunately, Tidalis is not an exception.

There are tutorials for just about every gameplay mechanism in the game. There are tutorials for the basic fundamentals such as match-three solutions and the need to keep the puzzle grid (called the “well” or “board” in the parlance of Tidalis) from overflowing. Then, there are tutorials for every special block, to cite more examples.

In fact, there are so many tutorials, there is an in-game menu which is dedicated to the tutorials.

It is the player’s interest to play them though, if only to spend less time learning about the game’s complexity the hard way when he/she encounters them in the other game modes.

DOCUMENTATION:

Another noteworthy tradition of Arcen Games is its virtually thorough documentation of its games. Tidalis benefits from this, fortunately. This includes a manual, though the manual is only applicable to the launch version of the game, which has since been superseded by many updates (the last was in 2011), each of which comes with its own exhaustive patch notes.

The documentation can be a lot to take in for players who are not used to reading, but for players who are, they should be adequately informative. Otherwise, there are always the tutorials.

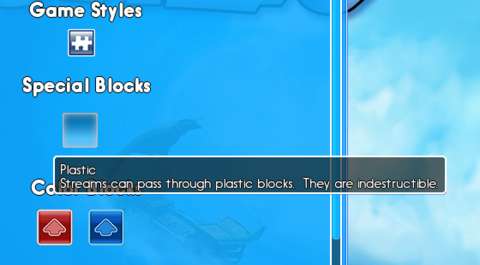

Most of this documentation is presented through reams and reams of text, interspersed by illustrations where relevant. If not this, then the documentation is presented in tool-tips (and long ones too).

IN-GAME HELP:

Interestingly, Arcen Games has invested effort into creating an in-game ‘help’ feature which the player might find useful.

This help system is actually part of the aforementioned documentation, specifically the documentation on the game modes, blocks and other gameplay mechanisms. It includes illustrations such as the symbols for the game modes (more on these later) and the sprites for the blocks, which make for easy visual association.

As for the text which verbally describes these things in the game, it is included in the tooltips which appear when the player hovers the mouse cursor over them. This is a very convenient presentation; the help screen would have looked very cluttered otherwise.

The nuance of this help system is that it contains filters which reduce the information in the database of the help system to a package which is pertinent to the current level which is being played. It can be accessed through the menu which comes up after hitting the “Esc” button.

On the other hand, using this feature also brings up a minor gripe. The buttons for the Help feature and resuming the current level are positioned on the upper right edge of the screen. This is not an issue for people who play the game in full-screen of course, but for those who play the game in windowed mode, this can be a small irritation.

REMARK ON COMPLEXITY:

With all of the aforementioned tutorials, documentation and filters for in-game help, a player should have no excuse for when he/she is bewildered by the complexity, e.g. when new blocks are introduced in the Adventure mode (hereby referred to as the “Adventure campaign” to prevent any confusion with “game modes”).

However, it is not as easy to pin the blame on the player when he/she gets frustrated by the game’s complexity. This is because as much experience, familiarity and intellect as the player has, he/she has no control over the random elements of gameplay, namely the composition of blocks which drop down into the board from the top.

As will be explained later, some aspects of the game’s complexity, especially the special blocks, would make these already fickle gameplay elements even more frustrating.

ARROW BLOCKS:

The most basic of blocks are the blocks with arrows on them. These arrows are associated with the mechanism of “streams”, which will be described later because it is another fundamental design in the gameplay of Tidalis. Nonetheless, blocks are mentioned first because they are generally the primary source of streams.

The majority of the arrow blocks are also coloured, which further influences the mechanism of streams; this influence will be elaborated later. For now, it should suffice to say that the colours which have been chosen for the blocks – cyan, blue, red, yellow, green and magenta – are visually contrasting enough, at least for people who are not colour-blind.

Speaking of colour-blindness, there are options which cater to the colour-blind, though this is not exactly made very clear by the game. For such folks, there is an option which include distinct shapes on the surfaces of the blocks.

These options can be accessed through the settings menu. There are other options, such as one which applies a 16-bit look to the blocks (which fans of retro graphics might find endearing).

Regardless of the visual designs of the options, there are – fortunately – always arrows on the surfaces of the blocks, for practical reasons which would be clear shortly.

STREAMS:

“Streams” are flows of glittering particles which appear from the first block which the player clicks on. These flows follow directions as dictated by the arrows on the blocks, changing directions as it passes from block to block.

If a stream crosses three or more blocks of the same colour before it terminates, these blocks are subsequently removed from the board and the player gains points to his/her score counter. The blocks above these disappearing ones then fall downwards, according to the setting of gravity which has been imposed on the level (more on this later).

It is worth noting here that the player can rotate blocks which are in the way of incoming streams to divert them away; there is also a tutorial level which highlights this. This rewards reflexes on the part of the player, though intellect for planning is still a more important asset which a player should have (other than luck).

Fortunately, for players with less alacrity, having the reflexes to perform this is not always a necessity to solving puzzles.

Blocks which streams have already passed through cannot be affected by other streams. This is not a design which the game will frequently remind the player about, but there are tutorial levels which mention this, fortunately.

One of the most useful tricks for linking up blocks with streams is to have blocks rebound streams, or have them make “U-turns”, to use the parlance of the tutorials for the game. Conveniently, there is an option in the settings menu (called “Smart Drag”) which helps make U-turns a lot easier. This is very smart programming on the part of Arcen Games.

There are plenty of other tricks with streams, all of which are taught by the game’s tutorials on “advanced topics”. Keeping these in mind to solve brainteaser levels or to seize an opportunity when a player sees it in other game modes can be satisfying. (However, for the latter case, the player has to be lucky enough to obtain this opportunity in the first place.)

GRAVITY:

Gravity is an ever-present effect in any level, regardless of game modes. There are some game modes which affect it, but there is not any which completely remove it from the levels; the closest which does this is Solitaire mode, but even this one still makes use of gravity for “draws” of blocks.

The effect of gravity is apparent in game modes where new blocks fall from the top into the board.

The most important contribution of the mechanism of gravity is to the planning of combos. After clearing the blocks beneath them with chains or combos (more on these later), coloured blocks with arrows which fall immediately emit streams when they land; this occurs without the player’s intervention.

Thus, the player may be able to plan combos by making use of this. In fact, falling blocks are the main way for the player to form combos of chains of different-coloured blocks.

However, this behaviour of falling blocks is much more useful in brainteaser and Zen mode levels, which give the player the time which he/she needs to predict the falling of blocks. In game modes which are more urgent, the behaviour of these falling blocks can be difficult to manage.

This is of course not entirely an issue of luck, because a keen-eyed player with great reflexes can prevent falling blocks from causing too much trouble. However, an observant player with quick reactions and considerable intellect is a very, very rare player indeed; if Tidalis is targeted at such players, Arcen Games has made a terrible business decision.

That remark aside, gravity also contributes to the timing of the streams. The timing of the streams is not just affected by reflex-based techniques such as rotating blocks at the best moments; it is also affected by the occasions when falling blocks line up with static ones so that streams can pass through.

The player also needs to have the reflexes necessary to pull off the timing of the starting of streams. Again, this rewards alacrity on the part of the player, which might not please players who prefer that intellect be the true factor of success. Nevertheless, to players who prefer to have all of their aspects tested, this can be satisfying.

However, outside of brainteaser puzzles and Zen levels, exploiting the contributions of gravity is quite difficult. This is because in other game modes, new stacks of blocks fall in random patterns, which can either mess up a player’s plan to do this or somehow trigger a massive cascade of disappearing blocks (whether the player desires this or not; read the sections on combos and chain reactions).

CHAINS:

A stream which has passed through three or more blocks of the same colour and terminated itself is considered to have created a “chain” of blocks, to use the game’s own terms. A chain of blocks is a sequence of blocks which is about to be cleared (and henceforth referred to as “chains” for ease of writing).

This is, of course, the game’s take on the match-three gameplay of its ilk.

Anyway, three blocks are the minimum for a chain to be created, but the player can attempt to link up more in order to clear blocks and score more points. However, this comes with some risks: the chain of blocks stay until the streams terminate, which is not desirable in urgent game modes. Furthermore, in any game mode other than Frenzy, as long as there is one stream or more in the board doing its thing, the player cannot start any further streams.

Interestingly, the game has a nuance about streams of the same colour which flow adjacent to each other; they merge and are counted as one chain. The most important consequence of this nuance is that streams which do not meet the minimum number of blocks can merge with others to form chains which do meet the minimum. This is especially of use in Frenzy mode, which grants the player the ability to start streams without waiting for earlier ones to dissipate.

COMBOS:

Utilizing the aforementioned behaviour of blocks falling due to completed chains and emitting streams when landing, the player might be able to create chains one after another. The act of achieving this is called a “combo”, to use the game’s own term.

There is a term which the game uses to describe its gameplay, and which concerns combos. Perhaps for the lack of better words, this is “depth”, which is the number of chains that a combo has in a sequence and not simultaneously. This is exhaustively described in one level within the Adventure campaign; the level even includes an analogous description comparing this difference with familial lineage.

“Deeper” combos usually score more points than combos which clear the same number of blocks with simultaneously moving streams. Of course, “deeper” combos happen to take longer time, which can be undesirable if the player wants to start new streams as early as possible.

Combos happen to score more points than chains, block for block cleared. This is apparent from the gaudy but otherwise translucent point indicators which pop up whenever the player clears blocks.

However, score is not always the player’s objective (despite the exhortations of the tutorials). In fact, there are some levels in the game where achieving more combos over achieving longer chains is not always desirable.

This contrasts with other levels where the objective is to score combos over chains. This difference is noticeable to players who actually read the text in the game, but for players who are too lazy to read or adapt their strategy, the constantly changing objectives (which is the case in the Adventure campaign) can be difficult to cope with.

STACKING ABOVE BOARD:

In every game mode except Brainteaser and Zen, having blocks stack above the grid layout of the board ends in a “game over”. This is, of course, quite typical for a match-three game with gravity-including gameplay.

However, losing this way is not simply just having falling fresh blocks stack over the grid, like they would in Tetris or less complicated block-clearing games. Rather, there are other ways for blocks to stack over the board – some of which the player can do little about or require considerable reaction speed on the player’s part to prevent or mitigate a disaster.

These ways are mainly associated with the game modes for Tidalis, which will be described shortly.

GAME MODES:

One of the ways which Tidalis differentiates itself from its peers is through its variety of game modes, but this difference is not necessarily for the betterment of the game. This is because they make use of luck as a factor of success to varying degrees, and some of them require more reflexes than intellect on the part of the player.

Most levels make use of the “normal” game mode. In the “normal” game mode, fresh blocks fall from the top of the board at generally manageable speeds, blocks have to be cleared through chains, and streams flow without any hitches.

Other game modes shake these up, or even include new gameplay elements – these are not always fun to deal with.

One of the game modes which straddle the line between manageable and unpredictable is “Graviton”. In this game mode, streams are affected by gravity and thus move downwards faster, but can barely move upwards. They also fall in arcs when moving horizontally.

Spending some time with this game mode in a less hectic level would help a player figure out the limitations of the streams. However, the player would also learn that these limitations are more predictable when the streams are passing through immobile blocks. If the streams are passing through falling blocks, considerable reflexes are needed.

Another commonly encountered game mode is Frenzy, which has fresh blocks falling at a far faster rate, but to compensate, the player’s limitation on starting streams is removed. However, this should not be construed as an equitable compensation: the player is far from being able to win by starting streams willy-nilly.

Some of the game modes are not kind to players with bad luck though. An example is Water mode.

Before elaborating on this statement, the fundamentals of Water mode have to be described first. The board is partially (or, rarely, fully) submerged in water; the game refers to the “board” as a “well” in this case, which suggests inconsistency about Arcen’s own nomenclature for the game.

Blocks still fall, or rather, sink anyway in water, but they do so more slowly. This aspect of Water mode is manageable.

The bubbles which form under the board are not as manageable though. The bubbles appear under the board, floating upwards and pushing up columns of blocks until the bubbles reach the surface of the water.

The game does attempt to mitigate this complication by warning the player of incoming bubbles through the visible formation of the bubbles, but there is no way to control which column of the board a bubble would appear under.

There are no tutorials for game modes, unfortunately, so the player must learn about them through hands-on trials.

BRAINTEASER LEVELS:

The best game mode in the game is perhaps Brainteaser. In this game mode, the number, location, orientation and types of blocks are set, and no fresh blocks would fall. Therefore, to the pleasure of players who prefer brains over reflexes and luck, intellect for planning is the only factor of success in this game mode.

The player can test his/her own guile with Brainteaser puzzles. Brainteaser levels are also where gameplay mechanisms such as the speed and direction of a stream can be appreciated to its fullest. Solutions requiring reflexes are also easier to pull off in this game mode because of the lack of randomness in the blocks. In other words, Brainteaser levels have pre-arranged blocks, which the player must clear in order to succeed.

Indeed, one could consider that the brainteaser levels are closer to being puzzles in the technical sense than the levels in other game modes.

Some brainteaser puzzles also make fun use of the need to consider the timing of the streams so that streams can reach certain blocks in time before they expire. To cite an example of a technique involving streams which is often used, many brainteaser puzzles require the rebounding of streams to reach blocks which had been passed by the same streams a few moments earlier.

Brainteaser mode also makes use of the feature to view the board after a “game-over”. This feature is available in any game mode, but it is more useful for brainteasers because the player can plan further moves to clear out blocks.

If there are anything dissatisfying about the brainteaser levels, it is that they expose a damning consequence of the complex designs in the game.

To elaborate, few, if any, brainteaser levels make use of special blocks with properties which are automated or out of the player’s control. This is especially so for special blocks with random behaviours, such as the Living Stone, which do not even appear in any official brainteaser level.

This points to a lot of wasted effort in designing the special blocks for anything other than game modes with randomness in their gameplay.

To cut Tidalis some slack, at least some of the more predictable special blocks are used. Chief of these are the white blocks, which resonate with and transmit streams of any colour but which cannot emit streams themselves. Indeed, knowing when and how to expend them is often key to solving the official brainteaser levels.

Another special block which is often used in brainteaser puzzles are locked blocks, one of which can be seen in an earlier screenshot. These do give away parts of the solutions, but they do not make the puzzles any less fun.

SPECIAL BLOCKS:

Special blocks had been mentioned earlier, and they would be elaborated further in this section. However, this elaboration would not be completely in praise of them.

In addition to the coloured blocks with arrows, there are blocks with properties of their own. Some have already been mentioned, such as the white blocks and locked blocks, and these happen to be of the sub-category of slightly altered regular blocks.

Then, there are blocks so peculiar that there are tutorials for them. It is in the player’s interest to consider playing these tutorials, because they demonstrate their properties quite well. Unfortunately, these tutorials will not prepare the player for how unpredictable levels would become when these appear in game modes other than Brainteaser and Zen.

The adventure campaign introduces them gradually, starting with the more easily understood ones such as the Tinder blocks, which have to be removed by creating an adjacent red chain. There are also other similar blocks such as the Turnip, but they actually have some nuances which make them more than just sprite swaps.

For example, the Tinder block can react with Fire blocks, eliminating the former, whereas the Turnip does not appear to have any other means of removal other than creating green chains next to them.

After that, blocks which cannot be removed by chains, such as stones and grilles are introduced. The game does mention how to remove them though, and this usually requires the player to send them to the bottom of the board and out of it.

There are also blocks which are virtually irremovable, such as plastic and metal blocks. Even among these blocks, there may be some differences; in the case of the examples which are plastic and metal blocks, plastic blocks let streams through, whereas metal blocks do not.

The problem with blocks which cannot be directly removed through chains is that they fall together with fresh blocks in game modes other than Brainteaser. They can fall in a stack with an arrangement which prevents the player from making streams, especially if the blocks are those which block streams outright.

After that, there are the less manageable special blocks. These blocks do not just sit where there are, waiting for the player to do something about them.

Firstly, there is the Eater block, which as its name suggests, eats away at blocks underneath it. Similarly, there is the Pit Monster, which eats blocks above it and poops them out its other side as charred blocks.

There are other examples which are notable, though not so because they are well-designed.

These are the fan blocks, which deflect streams away to other directions depending on the original directions of the streams. These are more usable in Zen or Brainteaser mode, but in other game modes, they bring a lot of undesirable complications.

The worst examples are the Living Stones. This is because they can move horizontally in either direction with no predictable rhythm, which render them outright unsuitable for Brainteaser mode.

ITEMS:

Some levels enable the use of “items”. These are usually blocks which the player can introduce into the board, while others function more like “power-ups” (to use the term often used for disposable items which produce immediate effects).

These items appear in the item toolbar and can be deployed by at any square in the board. In the case of items which create blocks, they replace the block which was originally in the square, if there was any. Power-up items deploy their benefits, with their benefits centred at the square where they are deployed.

Making use of items and handling the other game mechanisms such as starting and diverting streams can be quite a handful. This impression is further reinforced by the relative scarcity of levels which make use of the item toolbar in the Adventure campaign.

Items are generally obtained from clearing blocks which have icons of items on their top left corners; these items are then added to the toolbar, unless it is already full.

There is also a special block – called the Crystalizer – which when cleared, consumes the blocks adjacent to it and adds the latter to the item toolbar. Making use of this block to relocate other blocks, or even other Crystalizers, can be quite fun.

OBJECTIVES:

In just about every level except perhaps custom levels with Zen mode and easy settings, the player is given an objective which when achieved, completes the level successfully. There are also conditions for a game-over as well, clearly stated underneath the objectives.

Interestingly, the objectives are set completely by the game. In the case of the Adventure campaign, the objectives are already pre-set. For custom or quick games, they appear to be procedurally-generated, according to the other settings of the level.

For example, if the player picked very easy settings for the custom game, the game generates no objectives at all; it simply assumes that the player wants to “play for fun”.

Perhaps the game could have done better by giving the player the tools to set up objectives.

In the Adventure campaign, where the person who designed a level thinks that the pre-set objectives of the level may need clarification, there is a textual description of the objectives, together with a tip or two. This is appreciated, at least from the perspective of players who like exhaustive elaboration and do not mind reading. (These players happen to be the niche which Arcen Games targets, by the way.)

On the other hand, it may appear that the play-testers for the game had not read the text which had been prepared carefully, because there is some text which has a glitch.

ADVENTURE CAMPAIGN:

The “Adventure” segment of the game is the most immediately gratifying portion of the game, though “gratifying” may have been too generous a word to describe it with.

As mentioned earlier, the player character follows a bunch of weird creatures around, helping them solve levels. If co-op settings are enabled (through the main menu of the game), it is assumed that the other players are taking on the roles of the creatures.

There may be a suggestion of camaraderie, but such an impression evaporates when the other characters treat the player character like a hanger-on or as a lackey. Of course, one could argue that the story-writing is not intended to have themes of camaraderie in the first place because it is not serious, but the story-writing is not amusing either.

There may be some entertainment to be had from anticipating how bizarre the next character would look like, and if such anticipation is indeed what the game intends the player to have, then it does not disappoint.

As a representation of the player’s progress through Tidalis’s Adventure, there is a map which displays the lavish but incredibly bizarre landscape of the island of Tidalis. Button-like icons pop up as the player progresses, changing colours if the player either completes them successfully or skipping them outright after suffering a game-over.

Speaking of skipping, the player can attempt to breeze through the whimsical story by deliberately losing levels and skipping them; the game will not impede the player from doing this, conveniently. Skipping levels will not affect the story, which is perhaps a lost opportunity for the story-writing to make a poke at itself, given that its writer has declared the story to be one which does not take itself seriously.

Anyway, the map also has locales which when clicked on, unlocks brainteaser levels to play with. In hindsight, the game could have been more forthright in presenting its selection of official brainteaser levels, but discovering this for the first time can be amusing, as would the next few times that the player unlocks brainteaser levels by clicking away at weird-looking locales.

A minor complaint about the Adventure campaign is that the entirety of the database for the “Help” feature can only be seen from the map for the campaign. Another minor complaint is that the player is not informed in any way that to advance cutscenes, he/she has to click away at things in the cutscenes.

Unfortunately, there is a more serious complaint about the Adventure campaign.

This portion of the game is emblematic of the issue of the complexity of the game hurting its entertainment value. As the player progresses in the campaign, the levels become more frustrating to play, especially after the player breaches the triple-digit milestone. This is mainly because the objectives become less and less convenient to achieve.

For example, there is a level where the player has to wait out fire blocks, which eventually extinguish by themselves. At the same time though, the player must prevent the blocks from stacking above the board. Due to the random patterns of falling stacks of fresh blocks, this is as much a matter of luck as it is patience.

QUICK GAMES & CUSTOM GAMES:

If the player would prefer to have levels which are created on the fly instead of being pre-set like those in the Adventure campaign, there are the Quick Game and Custom Game features.

The Quick Game feature, as its name suggests, conveniently lets the player generates levels without fussing over their settings. The main setting which the player has is the vaguely defined and highly subjective difficulty slider, which means that the player might just end up with a level which is much easier than thought or much more complicated than expected.

The Custom Game feature is more reliable, if only because it has a lot more options. There are no options for setting objectives, because, as mentioned earlier, the game procedurally generates the objectives depending on the other settings. The game can feel a bit cheeky though, such as when it does not create any objectives if the player has chosen settings which it considers to be easy.

COLLECTIBLES:

For reasons which are never elaborated in the story, the island of Tidalis is littered with all kinds of things. There are detritus such as pocket lint and old tires, foodstuffs such as apples and oranges, valuables such as gold coins and jewels and unlikely things, such as teddy bears and toy robots.

The story does mention that the player character – and other characters – are indeed collecting these items, though for no reason other than entertainment or just to satiate their tendencies to hoard.

In terms of gameplay, they appear to do practically nothing. They can be amusing for the first few levels in the Adventure campaign though.

ACHIEVEMENTS:

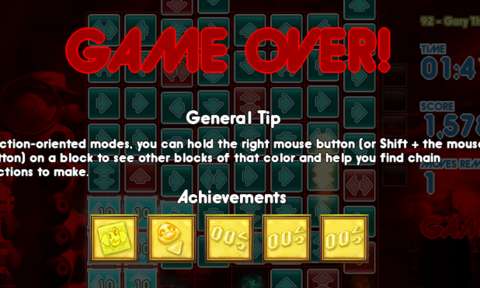

Tidalis was made during 2010, when the meta-game notion of so-called “achievements” was becoming rather popular. Arcen Games would not have its game missing out on this fad.

Tidalis has a lot of frivolous achievements, most of which concern the Adventure campaign and are just as whimsical as it.

As to be expected of “achievements”, there is not much in the way of gameplay-enriching substance to be had from them. Nonetheless, some of them may be amusing, if only because of their illustrations and accompanying text.

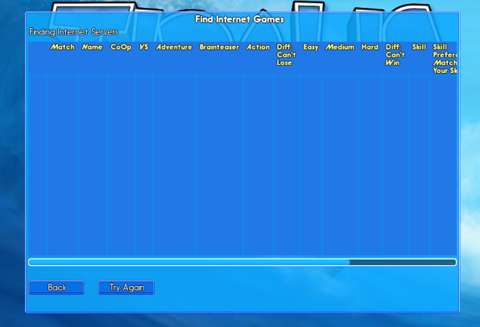

MULTIPLAYER:

Tidalis can be played with other players, though this requires some reading of the manual because the game does not include tutorials for multiplayer.

There can be up to four players joining in a session, but as the game describes with in-game notes, these four players are actually two pairs of two players, each pair using one computer in the case of LAN sessions or sessions over the Internet.

Yet, the game also has some amusing control schemes which may ostensibly allow three players to make use of one computer. Specifically, two players use the keyboard, while the third uses the mouse. It is a very uncomfortable set-up, but it may result in some short-lived hilarity.

The default setting for multiplayer is co-op. In co-op, the other players attempt to help the host of the session complete the level, with all of them working with one board.

However, playing co-op with a single board does not make a level easier. All players are subjected to the same shared limitation. For example, if there are streams going around in a level with the normal game mode, none of the players can start new streams.

At best, the other players – if they are truly cooperative – can attempt to help by rotating the blocks, but being unable to start streams means that they would have to wait. Of course, waiting is not always fun in multiplayer sessions.

Multiplayer sessions are more fun when they are played with two boards on screen; this is also the only way for one team of players to compete against another.

In co-op, both players – or rather, both boards – share the same objective and conditions to lose; both win if either achieves the objective first, but both lose when either flounders.

When playing cooperatively, either board’s players can deploy items which only appear in co-op settings. These items are variants of items which a player can otherwise use on his/her own board. For example, the co-op variant of the Fence item, which prevents fresh blocks from falling, can only be used on the other board.

When playing competitively, items can be used to either stymie the other board, or to give one’s own board an advantage. Considering that items appear randomly, lucky players may get an insurmountable advantage.

VISUAL DESIGNS:

Arcen Games had not been and still is not known for stellar visual designs in its games, and Tidalis would not be an exception to this generalized statement. Rather, Tidalis might have some loose artwork and doodles which Arcen’s artists have cobbled together for it.

This can be seen in the hideously bizarre and misshapen creatures which the player meets during the course of the Adventure campaign. The bulk of their animations consists of otherwise static sprites floating around, or being applied with filters where convenient. The other creatures, such as those in the background, have more animations, but they look even more unsettling due to the warping, twitching and undulating of their already hideous sprites.

Fortunately, the rest of the game’s visual designs are not made on a whim. Arcen Games makes it a point to ensure that some visual designs are meant for gameplay purposes in its games, Tidalis included.

Cleared chains of blocks produce discernible particle effects, the gaudiness of which can be reduced to the player’s preference.

When rotating blocks, the blocks which are not of the colour which the player is trying to manipulate is greyed out. This grants very convenient contrast to the blocks which the player is interested in. (In addition, only the highlighted blocks would be affected by the player’s attention.)

Blocks are generally immobile, but they do animate when the player would benefit from visual indicators that something concerning gameplay is occurring. The most commonly seen block animations are the trembling of blocks of towers which are close to breaching the top boundary of the board. This is handy, if only to catch the player’s attention.

SOUND DESIGNS:

Much like the visual designs of Tidalis, the game’s sound designs are whimsical. If the player has experienced other Arcen Games titles before this, he/she might not be impressed with Tidalis’s aural assets; he/she might even be annoyed.

Firstly, there is Pablo Vega’s music. Compared to his later works, the music in Tidalis sounds amateurish, especially his guitar tunes. It does, however, contribute to the whimsical nature of the game.

Arcen Games’ later titles do not have much in the way of voice-acting, and Tidalis might give a clue to the reason for this: the voice-acting in Tidalis is unpleasant to listen to.

Every character utters illegible gibberish, and even this is limited to just three or four clips, which are recycled over and over for many cutscenes. The gibberish is also made with forced voices, some of which can be grating, such as the one for the very first character which the player comes across.

Fortunately, cutscenes can be rushed through, so the player does not have to listen to these voice-overs. However, the same cannot be said about the sound effects which concern gameplay.

Most of these are comfortable to listen to, such as the tunes which play whenever the player scores combos and chains; these become more elaborate if the player performs better.

However, some of them can be grating to one’s ears. The worst examples of these are the sound effects for the Eater blocks.

CONCLUSION:

Arcen Games deserves a bit of credit for trying to create what it thinks to be a particularly sophisticated match-three puzzle game. However, its considerable complexity do not gel well with the tropes of the genre, such as the random patterns of the blocks which enter the playing field as older ones are cleared. This combination makes for frustrating gameplay where luck is rewarded just as much, if not more, than intellect for planning.

The complexity of the game does work well for its brainteaser puzzles, but Arcen Games and its playtesters did not appear to have recognized the strengths of the game.

Tidalis is not one of Arcen Games’ better known products, and perhaps it is better off this way.